by Cecil Brown

Dear Mr. President:

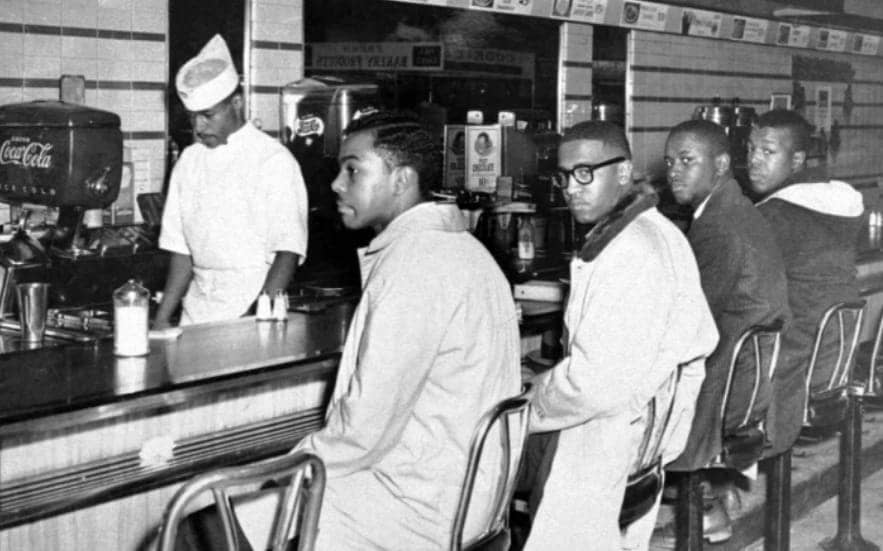

Feb. 1, 1960, marks the occurrence of a paramount historical event in the desegregation arena of the American South. This event occurred in Greensboro, N.C., at the lunch counter of the Woolworth store on Elm Street. This date is significant to many people, but it is especially significant to those who had active roles in the Greensboro Sit-Ins.

Mr. President, you have expressed kinship with the Greensboro Four and the quickly subsequent many other sit-inners. On July 17, 2009, you gave an important address to the NAACP Centennial Convention where you noted that the Greensboro Sit-In was “the catalyst that reignited the Civil Rights Movement after Rosa Parks in 1955.”

Fittingly, Mr. President, you ended your reference with a hearty salute to the Greensboro Four: “To the four young men who courageously sat down to order a cup of coffee 50 years ago, and to all who they inspired, I simply say: Thank you.”

Your words comprised a beautifully written and inspirational essay which displayed your accomplished writing skills. You exuded the affect of being there with those of us who were actually on the scene participating in the sit-ins.

I read the online issuance of your essay which appeared in the Greensboro News and Record – “Feb. 1, 2016: A Message from President Barack Obama: Greensboro Four left their mark on nation” – and it still resounds in my soul. It was an essay you wrote to commemorate the Feb. 1, 2010, opening of the International Civil Rights Center and Museum, which is located at the site of the February 1960 sit-ins.

You marked the “quiet dignity” of the simple act of asking for a cup of coffee. “The lessons taught at the five-and-dime challenged us to consider who we are as a nation and what kind of future we want to build for our children.” I compared your observation with that of those of us who sat at the lunch-counter protest, and I could sense emerging sparks of the “quiet dignity” revolution beginning to organize in the A&T College Scott Hall dormitory, where freshmen and sophomore men students were housed.

You wrote that “in 1960, four young students from North Carolina A&T (Agricultural and Technical) College walked into a Woolworth store in Greensboro, N.C., sat down at a lunch counter and reignited a movement for social justice that would forever change America.” Mr. President, you reflect the mood and aura of Scott Hall as if you in fact were there.

In Scott Hall and other dormitories, in the cafeteria, in other campus venues, students shared their tales of racist ills ranging from state and national institutional policies to blatant direct and personal insults. In the Scott Hall “bull sessions” we could let go and express layers of our “can’t breathe” moments.

I did not need a college professor to explain to me the significance between my family name, which is Brown, and the patriarch slave owner, Thomas Brown.

Who were we? And what warranted our confidence to stand up against the system that had prevailed for the duration of the country’s existence? Where did we get our authoritative and convincing confidence? What was the source of our energy? Where did it come from? In the overwhelming case, our fathers were not professionals; many of our mothers did domestic and menial level work.

When I arrived at A&T College in 1961, I still had within me the embodied memory of the Brown plantation that stood on the Cape Fear River. Grand-pap Archie Hatcher worked there in plantation overseer duties. And the shades of the big-house cast a cloud over everything I knew.

I did not need a college professor to explain to me the significance between my family name, which is Brown, and the patriarch slave owner, Thomas Brown. The older children of my extended family group pointed out the name Brown on the bricks stamped from 1805 and I could feel the plantation’s shadow having fallen over my family’s existence since the first brick was laid there.

Various other students I met at Scott Hall were from similar plantation links in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia and other locales. We were the first generation to obtain, in augmenting numbers, the leisure to contemplate and assess the horrendous effects segregation had on us.

Our dorm, Scott Hall, offered a setting and aura for our collegiate bull sessions. We were housed two to a room and most often we chose roommates from our hometowns or home vicinities. My freshman year roommate was James Randall, my “homeboy,” whom I had known since the first grade and on through high school.

Some upperclassmen were in our housing area, including Jesse Jackson, who was a junior. A significant core of our student life was anchored in the bull session. We frequently stayed up late at night playing dominoes, bid whist, checkers and chess. As we discussed every topic available and interesting to young Black men, we would contest in the games until winners and losers were determined.

As they sat down at the lunch counter, they realized that their action had risks as they challenged this symbolic icon of white supremacy.

Our discussions would range from politics and everyday concerns to Black thinkers and writers and artists such as Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison and John Coltrane and DuBois and Martin Luther King Jr., to existential writers such as Sartre and Camus. We had direct links to labor in tobacco and cotton fields, but we also had aspirations toward broader and extended horizons. We could see trails weaving from slave ship holds to the current cells of racial segregation and we knew that major changes needed to come.

On the Sunday night of Jan. 31, 1960, Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil reassured themselves that the next day would witness their sit-in action in the demand to be served, while seated, at the Woolworth lunch counter. When the Greensboro Four sat down at the lunch counter at 4:30 p.m. on Feb. 1, they realized that their action had risks as they challenged this symbolic icon of white supremacy.

The earlier day of Monday had proceeded as usual on campus with class activities and other matters. We had fine teachers and role models; for example, there was Dr. Darwin Turner, department chairman and professor of English. Suave in his dress and manner, he lectured to us about the genius of stalwarts of American and African American writers.

He had received his BA at age 16 and MA at 18 at the University of Cincinnati; by the time he was 25, he had received his Ph.D. degree from the University of Chicago. Spurred by his example and influence, I decided to major in English. I was even moved to imitate Dr. Turner a bit by smoking a pipe and wearing tweeds. He was also a chess player, and my classmate Jonas Thompson periodically engaged him on the board.

When I transferred to Columbia University at the beginning of my junior year, I was more than able to keep pace with the well-prepared students there in literature and other classes. We had some wonderful teachers at A&T, yet we were plagued by social and civic discrepancies outside the campus boundary.

“I had a very strange feeling; about 15 seconds before I was about to sit, I had a strange feeling of cleanliness. I discovered that I was not afraid. As I sat, I felt clean, relieved! I felt that I had gained a little bit of my manhood back by that simple act of sitting down!”

In the evening after the initial sit-in, The Four told us what happened at Woolworth’s. They purchased a few items to establish their identity as customers. Shortly afterwards, they contemplated the invisible counter line that segregated Blacks from whites, and they deliberately breached the demarcation. Vicariously, we, their audience in the dorm, followed their interdiction as if we were there.

Their act of defiance shocked those in the store. We relished hearing of their bold action. One waitress was so undone, she blabbered that they had better leave before they get in trouble. Franklin related to us that he was not scared; rather, he was just angry. He said that just as he was about to take his seat something came over him.

He turned to us and said: “I had a very strange feeling; about 15 seconds before I was about to sit, I had a strange feeling of cleanliness. I discovered that I was not afraid. As I sat, I felt clean, relieved! I felt that I had gained a little bit of my manhood back by that simple act of sitting down!”

Wow, we were impressed. It was an unexpected confession, to say the least. You could clearly see that something had happened to him, that it was a transformative experience. You could see it in his face. You could sense the importance of this rite of passage to a more solid Black manhood. We listened intently to his story as he related how the manager came over and told them to leave, but they responded that they wanted to be served and they did not budge.

Without really knowing it, the Four had become more assuredly men by acting and breaking mind manacles forged on them by segregation; they were regaining and restoring humane thefts imposed on African Americans by ill societal dictates.

A white woman of mature age approached those sitting-in and said: “Boys, I’m so proud of you. Why didn’t you do this 10 years earlier?”

Franklin noted: “But I was feeling so invincible, so powerful.” The real revolution was occurring internally, inside the person, according to the realization that before we can change the world, we may need to change ourselves.

A policeman had appeared, but he seemed somewhat confused and didn’t know what to do. The manager announced that the store was closing early. Sometime later, a white woman of mature age approached those sitting-in and said: “Boys, I’m so proud of you. Why didn’t you do this 10 years earlier?”

To be able to walk in and feel excited and powerful from breaking unjust laws was a feeling that had to be experienced on the personal level. After we were told what had happened by The Four, we wanted to join them – and we did.

On Feb. 2, more than 20 Black students, including four women, joined the group; on Feb. 3, more than 60, including Dudley High School students and students from the Black women’s college, Bennett College; on Feb. 4, more than 300 took part, including white students from the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina.

I shared Franklin’s feeling of awakened manhood, and the other participants could share appropriate awakenings in their manners. There were incidents of hate-laced heckling and even spitting during the protests, but our resolve was determined.

Mr. President, you wrote: “But they also knew what was happening to Greensboro and throughout the country was an affront to America’s founding ideas of freedom, equality and justice for all.” Some of the “homework” of addressing this task was plied in our bull sessions and provisioned, to an extent, with chess and other challenge backdrops, and nutritionally supplemented, in part, by Boss Webster’s bologna sandwiches.

The best bologna sandwiches at 3:00 in the morning were across Market Street at Boss Webster’s grill. In fact, it was the only place for us to get anything to eat at 3:00 in the morning. We claimed that Boss Webster made the best bologna sandwiches the world has ever tasted.

The main losers in our chess and bid whist games had to go across Market Street to get sandwiches for the rest of the players. In order to avoid this outcome of providing sandwiches for everyone, one had to hone one’s playing skill and win some decent games. To learn how to win and get to be treated with Boss’s bologna sandwiches was not a small thing in our world.

‘Boss was as much a part of the infrastructure of A&T as its academic programs.’

Boss was there until 3:00 in the morning flipping and preparing the sandwiches. He was the guy who sold us the sandwiches, but he also sold us the idea that we could do something about segregation. Another Market Street entrepreneur and civic advisor was Ralph Johns, a local merchant and NAACP member, whose clothing store was a focal point for goods and for civic advice and inspiration.

After over 50 years, my fellow English major classmate Jonas Thompson still remembers the preparation recipe of Boss’s bologna sandwiches. What made the sandwiches so good? Jonas mused to me recently on the phone: “He had to use a lot of grease. Also, he had a special sauce; he chopped and fried onions; he had a special flair of cooking the ingredients by turning them over rhythmically with a spatula. None of us ever got enough of Boss Webster’s bologna sandwiches.”

My literary studies college mate, James Pettford, remembers that “[Boss] was a character! What made him a character? First of all,” Pettford laughs, “He had a big, long, three-and-a-half-foot long roll of bologna. It was good quality, too.” I remember that scene.

“If he liked you,” Pettford went on, “he would slice you off a big slice. If he didn’t like you, you would get a thin slice, so thin you could see through it.” I asked, “How could you know if he liked you?” Pettford noted: “That was what was so weird about him. You never knew. The only way you knew was by the size of the slice. Some frat boys would say, ‘Boss, give me a fat slice,’ but that was a sure way of getting a thin slice.”

We of the bull sessions could attest to Boss’ significance, yes, but so could others salute him. According to an article in the Greensboro News and Record in 2001: “No one made a fried bologna and cheese sandwich at N.C. A&T like David ‘Boss’ Webster. Webster used to dole out sandwiches, as well as advice, to thousands of A&T students in the 1950s and ‘60s at his Triangle News Stand and Luncheonette on East Market Street.

“Hey, Brown, what does ersatz mean?”

“‘Boss was as much a part of the infrastructure of A&T as its academic programs,’ said Velma Speight-Buford, an A&T trustee and 1953 graduate. If he wasn’t making sandwiches, Webster was talking to students about their classes and the importance of an education. ‘He was a counselor, mentor and true motivator for getting people to stay in school,’ Speight-Buford said.”

Mr. President, in a respectful reference, you noted that we were influenced by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “inspired by the words and deeds of a young preacher who catalyzed a bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., Franklin E. McCain, Joseph A. McNeil, David L. Richmond and Jibreel Khazan – Ezell Blair, Jr. – decided that enough was enough.”

One might posit that we also had quite a handy student source of inspiration right among us on campus: one of our college mates, Jesse Jackson. Martin embodied a tremendous regional and national presence, but Jesse was one of us right there with us.

If you were in the ROTC, as I was, you were likely to see Jesse in formations because he was one of the notably active cadet officers; if you were in the band – I played tenor saxophone in the marching band – you saw Jesse because he played quarterback on the football team; if you were interested in student government, as my friend Pettford was, you would see Jesse because he was president of the student body; if you took Negro history, as Randall did, you had Jesse in your class.

My A&T classmate, Jonas Thompson, recently talked with me – he lives in Vallejo, Calif., and I live about an hour away in Berkeley, Calif. – about some leading figures, and he noted that “I always liked Jesse; even if he had never been famous, I would have liked him.”

I remember that, at A&T, Jesse had an effective habit of improving his speaking vocabulary. At one point he kept near him a book called “30 Days to a Better Vocabulary.” He would often quiz us on words: “Hey, Brown, what does ersatz mean?” That tactic was effective; I remember the definition to this day. Jesse was serious about improving communication skills.

After leaving A&T and Greensboro, we all “went off into the world,” off on our separate ways. Randall went to graduate school at Carnegie Institute of Technology, today Carnegie Melon University, then on to other education.

Randall went on to serve 40 years as a professor of English and African American Studies at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where, now retired, he is the Stead Professor Emeritus of English and African American Studies. The James H. Randall Intercultural Center is located there. The African American Museum of Iowa named him an Iowa History Maker in 2014.

We had not been able to hear ourselves think for 200 years. We were excited and we knew that we could be somebody.

Jonas Thompson became an early leading computer expert in IT. James Pettford obtained an MFA in writing from Columbia University. He did social work in New York City, worked in journalism in Florida and did social and civic work in North Carolina. He is currently engaged with writing projects, including the long-term project of his first novel.

When I went on to pursue my ambition to be a writer, I went to Columbia University, as, Mr. President, you did, years later. I discovered that, indeed, I had a talent for writing. After obtaining my MA from the University of Chicago in 1967, I went on to have good success with my first novel, which was published in 1969; other books would follow over the years.

I remain a professor at UC Berkeley. I was living in Berlin when a strange thing happened that brought me back to the Greensboro sit-ins in vivid terms. I was being interviewed by a German reporter when I was asked what I thought of the fact that Germans loved Black Americans. My awareness of this matter was not keen, and, as an example of this propensity, the reporter pointed out that Jesse Jackson, who had arrived in Berlin as part of his bid for the 1984 US presidential run, was more popular with the German people than John F. Kennedy.

More than 250,000 Germans had shown up for Jesse in Berlin alone. I mentioned to the reporter offhandedly that I had gone to school with Jesse. The reporter gave me a certain look which signaled that he was not sure that I was telling the truth. Nevertheless, he found a way to get me into the front area of the press conference that soon took place.

When Jesse looked over and saw me, he literally flipped: “Hey, man, how did you get here?” I had the same question for him. He signaled me to the motorcade accompanying him and I was taken inside his bus and met with a pleasant surprise! His wife Jackie was there. She was a fellow student “back in the day” at A&T during the 1960s when the sit-ins took place. Jesse and Jackie married in 1962 while they were students at A&T.

We were somewhat surprised that here we were, however haphazardly, converging outside of America, and we had once been at A&T in Greensboro, N.C., participating in desegregation actions, and we were here in Berlin reconnecting personally while Jesse was running for president of the whole system we were demanding just to obtain a cup of coffee from merely 24 years earlier.

And, of course, Mr. President, 24 years after this Berlin rendezvous of A&T sit-in veterans, you would be elected US president.

During Jesse’s stay in Berlin, I joined their entourage and accompanied them during the official dinners that Jesse attended. On the final night of that Berlin episode, we were in their hotel suite, and I showed them copies of my book in German, French and Italian editions, indicating that I was a bona fide literary celebrity in Europe. I was quite proud of them.

Many of us owe much to the sit-ins. Jesse seemed impressed, as he lay back on the bed, flipping through the pages and reading the jacket cover of my book. “You said you went to the University of Chicago?” he said. “Yes.” “You went to Columbia University?” “Yes.” Then, he looked at me, “What about A&T?”

He had me there. A&T was well imprinted within me, but its name was not scripted on the jacket. “You know you learned to write at A&T,” he chided. He was right about that, too. By the time I got to Columbia University, where I had transferred after my junior year, I had already been prepared by my professors at A&T.

Recently, I asked my friend Jonas, what was it about us that was so different from this generation? “Well,” he said, “We refashioned ourselves into an image of well-dressed young men with haircuts.” This has layers of truth.

We were interested in our self-growth; we were exploring all possibilities. We had not been able to hear ourselves think for 200 years. We were excited and we knew that we could be somebody. I might conclude that we need to re-educate – we need to re-educate our young people to heed models that are sincere and are seriously within African American traditions.

Mr. President, after contemplating my essay addressed to you, after a short reflective moment, I can say that the Obama achievement is the culmination of our collective dreams of the 1960s at A&T. We wanted a political voice. We wanted to be a legitimate part of the system. We wanted more than faint token instances here and there.

The Obama achievement was a fulfillment of the desire, of the dream. That dream included actual presence on the mountain heights, among scaled peaks. We had a president of our own acknowledgment.

“Obama fulfilled a lot of emotions that we had of ourselves. We came from slavery to having our own president. He was a continuum of our dream.”

In 2010, Franklin McNeil was asked about his relationship to the Obama presidency. He said, “We were a part of a continuum, and I believe that without that continuum, there would be no Black president.”

Mr. President, help me keep the memory of the Greensboro Four alive. Remember manifesting the ritual and the ascendance of Black manhood – and, of course, how, in one case, it was nurtured literally and figuratively by Boss Webster’s bologna sandwiches.

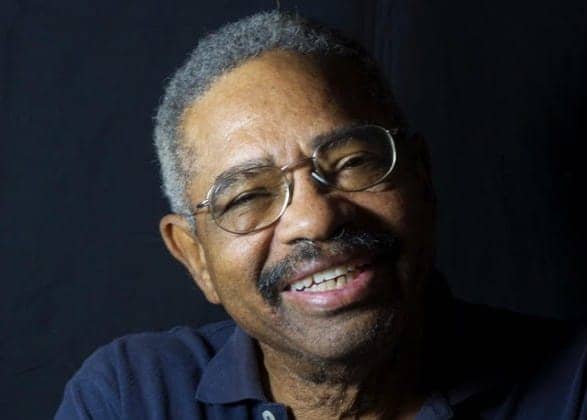

Novelist and educator Cecil Brown, UC Berkeley professor, is best known as the close friend, screenwriter and biographer of Richard Pryor and as the author of “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger,” “Stagolee Shot Billy” and most recently “Pryor Lives: How Richard Pryor Became Richard Pryor: Kiss My Rich Happy Black Ass.” Brown can be reached at browncecil8@me.com.