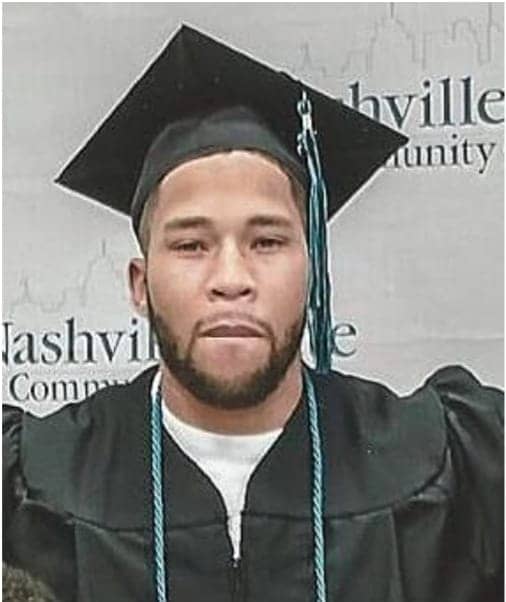

A cultural analysis by David Richardson

I am an artist; I just happen to find myself incarcerated in Only, Tennessee, at the present;

I am a poet; I just happen to be serving a life sentence plus 224 years right now;

I am a scholar, just also happen to be a convict at the moment.

I am Dave Rich, and this is only the beginning.

A man walks into a bar. The music stops. Conversations come to an abrupt halt. All attention is directed at him. Angry stares send a clear message, “Go away. Your kind is not wanted here!”

The message is received; the same energy is reciprocated. No, this is not the resistance met at a 1960s southern café by a Black man. This is the resistance he meets at the onset of his educational journey, today.

With education comes awareness. Frederick Douglass, in his autobiography, describes this terrifying illumination as a curse rather than a blessing. “It opened my eyes,” he begins, “to the horrible pit but to no ladder upon which to get out” (Pg. 53). I submit to you that we still find ourselves residents of this very pit. By “we” I mean Black men, specifically those who have lived a “street life,” and now find themselves incarcerated.

Though the following arguments may apply to many, my concern here is with the aforementioned group. Within these pages we will look at the repercussions of academia’s educational rejection of Black men, and the intense emotions accompanying this impasse. In doing this we will examine the main reason for this unwanted trend as illustrated in the life of slave-born abolitionist, Douglass.

We will then move on to the relevancy of this subject for educators and reformists, and how a more inclusive approach could work wonders for reducing the prison population. Then, we will look at possible solutions to this problem. But first, we must understand the Pit.

The Pit, much like Plato’s Cave, is a place of darkness and assumptions. However, unlike Plato’s Cave, in the Pit there appears to be no means of escape. The awareness that one is in the Pit is brought on by outside means. In Douglass’ case, learning to read opened his eyes to the world around him.

That is, we enter education with the generational trauma of pre-conceptions of white authors perpetuating pseudo-scientific white supremacist ideology and, similarly, Black-inferiority theory, that is canonized still today within academia.

The extreme emotions felt at this moment were especially difficult to process. “The more I read,” he began, “the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers.” Elsewhere he states, “I often found myself regretting my own existence, and wishing myself dead; and but for the hope of being free, I have no doubt but that I should have killed myself, or done something for which I should have been killed” (Pg 53, 54).

The very thing that is meant for liberation, we find, poses a unique stumbling block – for to educate oneself is to look in a mirror, but to see himself in this mirror is not an easy thing for Black men. The more he sees himself, the more he must contend with that image, for the image that he sees is one of white-induced inferiority.

Douglass went as far as wishing himself to have been born a beast rather than of African descent (Pg. 53). I tell you these sentiments are shared to this very day by many Black men. It is important that these feelings be addressed and studied in great detail, and that their cause be addressed, that a ladder of escape be provided.

Like a scarred-lover enters a new relationship, we embark on the journey of education. That is, we enter education with the generational trauma of pre-conceptions of white authors perpetuating pseudo-scientific white supremacist ideology and, similarly, Black-inferiority theory, that is canonized still today within academia.

For example, Scottish historian, David Hume, spoke this: “I am apt to suspect the Negroes to be naturally inferior to the whites. There scarcely ever was a civilization of their complexion, nor even any individual, eminent either in action or speculation” (Pg. 213). While German philosopher, Georg Hegel, went as far as promising not to even mention Africa again, for he claimed it had “no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit” (The Philosophy of History).

Notions of Black-inferiority are not limited to Enlightenment-era thinkers only. We could go as far back as Aristotle and, no doubt, work our way well into the 21st century with men who defended Black-inferiority and who are held as pillars in classrooms today. This thought is troubling for a segment of the American population. So troubling, in fact, that “white only” signs might as well still be erected outside learning institutions.

Is there, then, any wonder why education doesn’t appeal to the aforementioned group in the same measure as others? Is there, then, any wonder they are left feeling educationally disenfranchised?

I am now a junior in my bachelor’s degree studies and have not yet had a Bishop Desmond Tutu required reading, nor a Na’im Akbar theory, nor excerpts from a Kwame Nkrumah, and certainly not a Cornel West text. However, I find myself bombarded with great thinkers of yesterday who enlighten us all to great truths, but also happen to think of my ancestors as a subspecies of the human race.

An immoral system will not fail to corrode itself from the inside out. Frederick Douglass makes a point of mentioning that his once friendly mistress, who had at first helped him learn the alphabet was, by the iniquitous practice of chattel slave owning, transformed from a kindly woman into a person of spite and malice. “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me … Under its influence [her] lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness” (Pg. 50). In the same way education has decayed from its noble ambitions, for just as slavery proved harmful to slave owners, so also academia will find itself suffering for its poor attempt at integration.

So troubling, in fact, that “white only” signs might as well still be erected outside learning institutions.

What relevance does the subject have for educators and reformists? Consider that African Americans make up barely 13 percent of America’s 332 million person population but more than 40 percent of its prison population (Race and ethnicity/Prison Policy Initiative). We, therefore, have a significant percentage of the prison population that my findings may very well apply to.

Now, consider the reformative power of education. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has found that there is a 43 percent reduction in recidivism for prisoners who participate in education programs with an emphasis placed on higher education. “The higher the degree,” the report claims, “the lower the recidivism.”

The report goes on to cite a study conducted by the Department of Policy Studies at the University of California at Los Angeles that finds that: “a $1 million investment in incarceration will prevent about 350 crimes, while that same investment in [prison] education will prevent more than 600 crimes” (Northwestern University). This tool has the potential to be far more effective if a more inclusive approach to educating is taken, one that doesn’t marginalize whole groups of people.

But, what should such an approach look like? As stated, the emotions I’ve described are experienced early in a Black man’s educational experience, therefore this problem must begin to be addressed at the primary-school level.

Several attempts to create an all-embracing educational space have been put forward over the years. One such approach that explicitly addresses the concerns I’ve raised is known as Critical Race Theory. The theory, created by civil-rights scholars and activists, aims at examining the intersection of race and law in America. The results are ugly but true.

Opponents say the theory teaches racism toward and hatred of white people. Some state governments go as far as withholding money from schools that teach the theory or anything akin to it. This opposition amounts to little more than fear-mongered white fragility that seeks to silence that which threatens its conscience.

Other solutions include ingraining the works of Black thinkers within the framework of college classes rather than having a separate class for, say, African-American literature. Although the purpose for having such classes is warranted, this purpose cannot be used to exclude Black thinkers from the canon of great philosophers as represented in college classrooms. The reality of America’s past must be faced head-on, not swept under the rug.

The conversation on race must be revisited each generation, otherwise, the emotions of the Pit will continue. We must get better at understanding ourselves and others.

The problem I’ve presented to you is one of particular interest to the Black community, but requires a solution with the assistance of all Americans. Let’s make the words of Broncos free safety, Justin Simmons, true: “All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter.”

mwisho

Send our brother some love and light: David Richardson Jr., 00520117, TCIX, 1499 R.W. Moore Mem. Hwy., Only, TN 37140.

Works Cited:

Douglass, Frederick. Frederick Douglass: The Narrative and Selected Writings. Ed. Michael Meyer. Modern Library College Edition. New York: Random House Inc., 1984. Print.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The Philosophy of History. Trans. J. Jibree. New York: Dover,

1956.

Hume, David. Essays: Moral, Political and Literary. Cosimo Classics, 2006.

Northwestern University. 21 Feb. 2022. Document. 28 Feb. 2022.

Race and ethnicity / Prison Policy Initiative. 21 Feb. 2022. Document. 28 Feb 2022.