With her classic book newly republished, former Black Panther Party leader Elaine Brown spoke to Yuri Prasad about life in the revolutionary group and anti-racism today

by Yuri Prasad, Socialist Worker

Elaine Brown is one of the last surviving leaders of the Black Panther Party. The revolutionary group was famed for its uncompromising fight against racism and capitalism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In particular, the Panthers were known for their Marxism and for being prepared to bear arms.

Brown was a talented rank and file member who joined the organization at its high point in 1968. She rose to become the editor of its newspaper, its minister of information and, ultimately in 1973, its chairwoman. As the group struggled to survive state assassinations, bomb attacks and FBI‑instigated internal fights, Brown held the Panthers together.

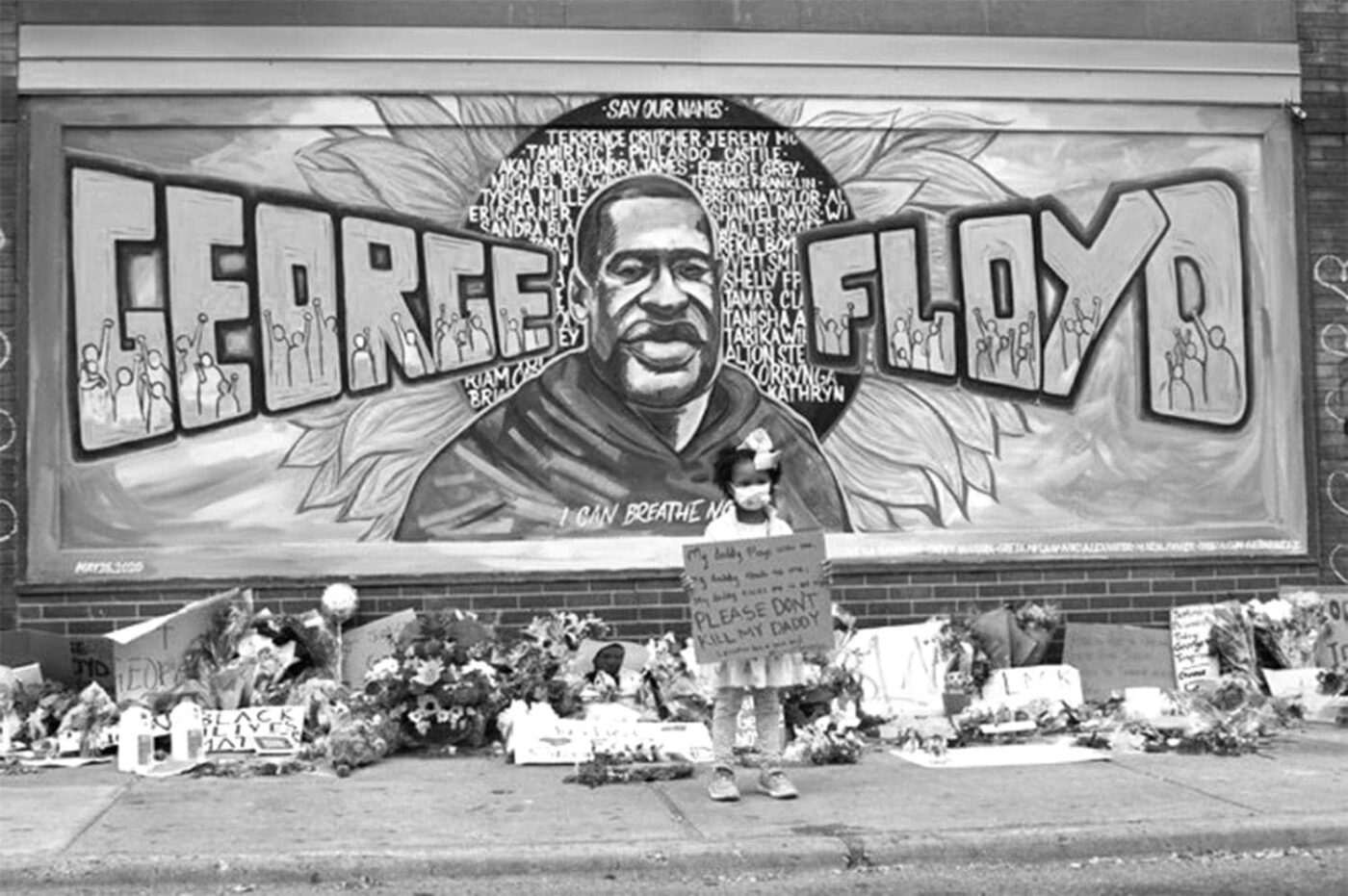

She talked to Socialist Worker about revolution and the themes of her republished book, “A Taste of Power – A Black Woman’s Story.” We began by discussing the wave of Black Lives Matter protests that followed the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. And we talked about the differences between those fights and the struggles of 50 years ago.

“I have said many times that I don’t see where there’s a movement here. There’s just a slogan,” Brown declared. “The only thing that is similar is the process of becoming aware of the conditions that cause so much pain.”

For Brown, the key questions are strategy and political organization. In this she insists there are marked differences between what was happening in late 1960s America and what is happening now.

“I don’t see anything like the Black Panther Party or the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or any other organization that has been formed as a result of this collective rage,” she said.

“Certainly not one that is actually addressing the causes of the problems. Who is dealing with all of the issues that George Floyd’s murder represents, which are the poverty of Black people, the continued oppressive state, and so on? I don’t see anyone challenging the United States government.”

“We kicked open doors to create these positions for elected officials who pretend to have some consciousness but don’t do anything.”

Brown has clearly thought hard about why no organization emerged from Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. At its height this movement was able to mobilize thousands of people, often in pitched battles with the police. “There are things that are true today that were not true back in my day,” she explained.

“The conditions are such that a number of Black people have arrived at a level of comfort. They’re not really afraid of getting killed by the sheriff if they go out to vote.” That “comfort” is something that the mass movements of the 1960s created, Brown thinks.

“We kicked open doors to create these positions for elected officials who pretend to have some consciousness but don’t do anything.” And this “comfort” has in turn created “a reliance on the system” that promises to “address all these ills” without really demonstrating what unites them.

“It’s as though they’re not tied together,” she added. “And, because of that, they are not really talking about capitalism. That’s why it doesn’t translate into anything concrete. Dr Martin Luther King talked about the ‘urgency of now.’ There’s no sense of urgency now.”

A second reason for the lack of organization that Brown pointed to is fear. “Nobody wants to give up anything at all to accomplish this. Nobody’s willing to say, as Dr. King said, and as we in the Black Panther Party said, ‘I’m ready to die for this’. And people did die – my comrades and all the other people who sacrificed their lives.”

Brown also highlights the way the establishment and the media have framed the discussion of the fight against racism in the 1960s and ’70s. This has limited the narrative to one of democratic rights in the Deep South.

“We could see Black people being hosed by the police. So today we think of civil rights as fighting against Black people being hosed because that’s what we saw via television.”

Looking back to how she became a revolutionary in 1968, Brown said she felt there was very little choice for people like her. “By the time I stumbled upon the Black Panther Party in Southern California, Huey Newton had been involved in a shootout with police in West Oakland,” she explained.

“He had become a national hero for Black people. Not because he was a victim like George Floyd, but because he was alleged to have shot that cop that would have killed him.

“I had been thinking that I was a conscious Black person, doing my writing for the little newspaper in the Black Congress organization I was involved in. Everybody was militant. Everybody was everything until the Black Panther Party came and drew a line in the sand.

“They said, ‘Well all this is nice, this conversation, but Huey Newton has just been charged with killing a cop.’ So you’re talking about police brutality, you’re talking about this stuff, but you’re really not making a move. So the difference is now going to be that we have to take action.”

The question the Panthers put was, according to Brown, “Do you want to keep on playing around with what you’re doing and thinking that you’re doing something meaningful, now that you know it is not meaningful?”

For Brown, the answer’s clear. “What else can you do but surrender your life to the revolution?” she asked. In the late 1960s as the “revolution” grew to embrace women’s emancipation and gay liberation, the Black Panthers increasingly incorporated the issues into its programme.

Brown remains convinced that revolution should still be the aim for people fighting for change today.

“The party was dominated by men. Even though there are people who would like to pretend that at some point it was mostly women, that’s just not true,” Brown insisted. “But I would say that every one of the sisters that I knew were all tough broads. And we had to be tough when we joined the party. We didn’t join for some man; we were revolutionaries.

“The mainstream women’s liberation politics of the time, represented by people such as Gloria Steinem and her Ms. magazine, wasn’t arguing for fundamental change in America. They just wanted to make sure women broke through the glass ceiling, so that we too could oppress people and become corporate leaders like men did.

“But the Black Panther Party and the parties we were affiliated with were the only organizations that identified the question of women’s liberation and gay liberation as a part of our overall struggle.”

Brown remains convinced that revolution should still be the aim for people fighting for change today. “Is it a goal? All I know is that it is my goal. We will never be a free people without it,” she exclaimed defiantly. “The word might be confusing or scary. People like to think that it’s some kind of 1960s word.

“But the bottom line is that the Empire of the United States, which has caused our enslavement, cannot continue like this. We cannot continue with this world system. Most people are poor, and yet some are so rich that it is almost unfathomable.

“But in order for them to have that wealth, the rest of the people have to be poor. It’s a requirement. I’m not all right with the current scheme of accepting mass oppression and poverty.”

Looking back at her time in the Black Panther Party, Brown is rightly proud of its achievements. “My old comrades and I talk about it even now, and we say it was the best time of our lives and we were putting our lives on the line. We loved the party. We loved being in the party. We loved it though it was hard.”

Yuri Prasad writes for the Socialist Worker newspaper. His research into Asian workers strikes across the 1960s and 1970s culminated in the article, “Here to Stay, Here to Fight: How Asians Transformed the British Working Class” (2016), which was published in the International Socialism journal. He also contributed to “Say It Loud: Marxism and the Fight Against Racism” (2013). Yuri is author of “A Rebel’s Guide to Martin Luther King” (2018). He is advisor on the Strike at Imperial Typewriters project. This story first appeared in Socialist Worker.