by Joergen Ostensen

Southbound into Queens on Interstate 678, there’s always heavy traffic, crashes at every turn, wailing ambulance sirens, unhoused people begging for food and, of course, cop cars swerve through traffic, endangering everyone as they racially profile their way to ticket quotas and six figure pay checks. For miles of start and stop driving, those who know where to look can see the Queens Criminal Court, which looms above the highway, a dark shadow through the thick pollution haze.

Prakash Churaman, who will be 23 this summer, will be retried for murder in that building sometime in the next couple months. He’ll have to show up there for weeks straight, but that will be nothing new because the struggle has been Prakash’s whole life ever since he was 15; ever since NYPD officers entered his mom’s house before dawn and took Prakash to the 113th precinct, a 15 minute drive that took 4 hours.

There Prakash, who immigrated from Guyana with his family as a baby, was coerced into making a false confession. The detectives, specifically Barry Brown – who got paid well over $100,000 in annual salary – knowingly exploited Prakash’s youth, the fact that he is intellectually disabled as well as his and his mother’s ignorance of the English language and their civil rights.

Prakash said on tape he’d tell the cops whatever they wanted to hear, so long as he could go home. From that point on, Prakash entered what he has referred to as a nightmarish and diabolical maze – seven plus years of uninterrupted carceral control – juvenile detention, Rikers Island, prisons across the state as far as Buffalo, back to Rikers on remand status when his conviction was overturned and now, for the last 16 months, house arrest with an omniscient ankle monitor.

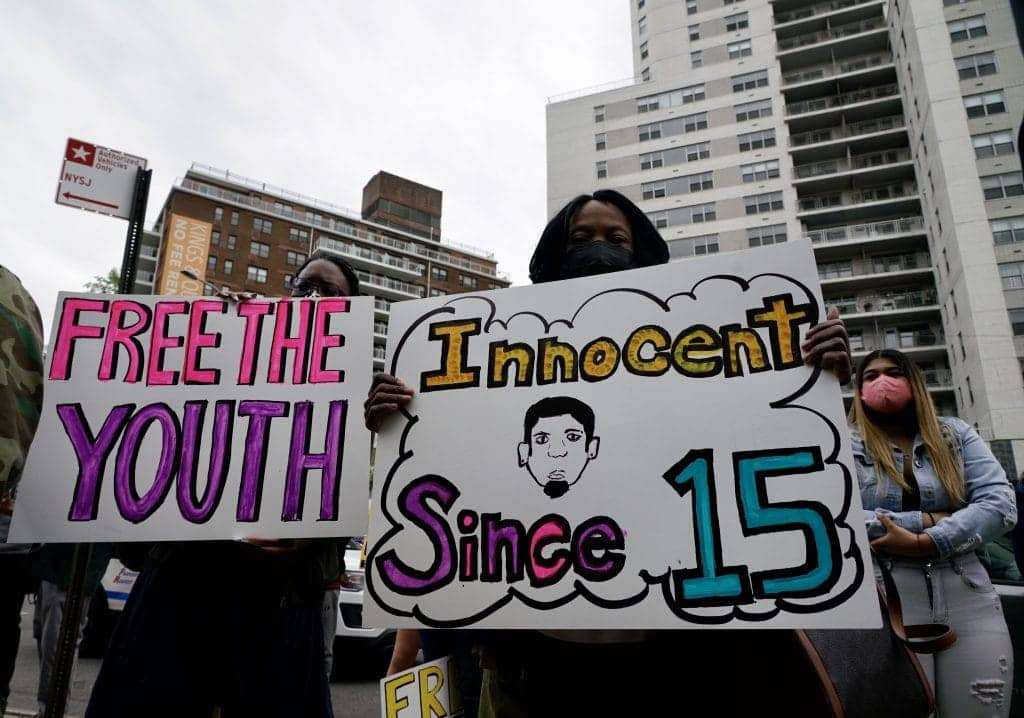

Prakash has maintained his innocence since he was 15. Two weeks into his incarceration, he wrote a letter to his mom, where he clearly articulates that he had nothing to do with the crime.

In 2016, Prakash met Jacob Cohen, who at the time worked on Rikers in an art program. Jacob is a cellist and sketch artist, he used to draw portraits of the kids in lockup. He has a book filled with hundreds of faces he drew there, the faces of the system’s children. Prakash asked Jacob for help raising awareness of his story, and Jacob made a minute long video where he recorded Prakash on a call from Rikers which played over old photos from before his arrest.

Prakash explains in the video that his lawyer at the time was not communicating with him, so, despite having almost no high school education, he was doing his own legal research while filing his own motions and petitions.

For the first time, Prakash publicly declared his innocence and indicted the system, saying: “This justice system is very unjust … it’s hard to be innocent and poor at the same time.”

Judge Holder banned him from speaking at his own rallies and threatened to send him back to Rikers.

The Department of Corrections fired Jacob and banned him from Rikers immediately following the video’s release. Jacob, who now makes his living by playing homemade cellos on street corners and in the subways, did not give up on Prakash’s fight. He was able to help bring on the respected civil rights attorney Ronald Kuby as Prakash’s lawyer.

But even Kuby was no match for Prakash’s biggest opponent, the allegedly honorable Kenneth Holder. Holder, who was born in England, is also an immigrant of color. He spent 25 years sending people to prison while working as a prosecutor before taking those skills to the bench. Holder disallowed the defense’s main argument, which would have been expert testimony on the subject of juvenile false confessions.

When called upon to make their case in court, Kuby had no choice but to simply say, “The defense rests.”

Prakash was convicted by a mostly white jury and sentenced to nine years to life, which he thinks of as a death sentence. He is well aware that as long as the last word is “life,” the state can keep him in a cage until he dies.

A friend and mentor of his, named Salih Abdullah, who Prakash knew in prison, went to 14 parole hearings and died of a stroke in the last one, when they were finally considering letting him out. Salih spent 47 years in prison and was 74 when he entered heaven.

Prakash filed an appeal and never stopped believing he would one day be free. In June 2020, shortly after the execution of George Floyd caused rebellions all across the so-called United States, and shortly after Prakash celebrated his sixth consecutive birthday in a cage, his conviction was overturned by an appellate court.

Six years in, Prakash was, again, “innocent until proven guilty.” Holder denied Prakash’s request for bail and remanded him back to Rikers. Prakash returned there, believing he could use the jail phone and social media to drum up the support of community organizations, civil rights lawyers and journalists. He believed that he deserved more attention, more support from his community and, of course, freedom.

I met Prakash in July 2020, while working on an abolitionist journalism project developed by an incarcerated trans person called #PrisonsKill. I recorded an interview with Prakash where he spoke at length about his side of the story, something that was often omitted from articles about the case. Prakash asked me to help him connect with organizations and resources that might be able to help him.

Myself and other abolitionists connected to Prakash started circulating a petition and fundraiser but struggled to gain any community support in Queens, despite the fact that we tried to reach almost every group and activist organizing around mass incarceration. Most folks simply declined his calls, especially when they recognized they were from the jail phone.

In those days, some of the most intense of the pandemic, Prakash and I often spoke multiple times per day. He’d ask me to set up three way calls, post on social media, or write messages to his friends and supporters. I often dreaded his calls because all I had to tell him was bad news.

Prakash’s incarceration has been the single greatest impediment to justice in this case. In a video I recorded, Prakash told me: “[Incarceration] hinders me from being a part of this movement I’m trying to put together … I don’t have the resources and materials I need. I don’t have internet, which is the key to networking and connecting with other people … I have a pen, a paper and a phone I can call a few times a day. That’s pretty much it.”

In the video, Prakash sits in front of a monitor on Rikers wearing a gray jumpsuit with DOC on the back; police hover in the background.

In November 2020, Prakash’s new lawyer, Jose Nieves, who replaced Kuby because Kuby wanted Prakash to plead guilty, attempted to get bail set so Prakash could prepare his defense and movement from the free world. Judge Holder denied this request and said that based on the first trial, freeing Prakash would put the community at risk because the evidence against him was “strong and compelling.”

Holder still has not heard the evidence the defense tried to present the first time. This sent a clear message to Prakash that Holder believes in his guilt and will continue to be biased.

This court date also was the first time I saw Prakash in person. I remember we were not even allowed to wave, only fleeting eye contact as I sat in the back of the courtroom. Three armed guards were strategically positioned around him, his hands were covered in mitten shaped restraints.

A month later, Holder’s bail decision was overturned on appeal and the ransom was set for $150,000. Basically through random chance and a single phone call on a snowy day I was able to get $15,000 from the National Bailfund Network, which was enough to enlist the services of a bail bondsman.

Others helped find signatories to guarantee the full bail. The campaign also had to find an apartment where Prakash could live with his mom, secure housing being a condition of his release.

Prakash was released to home confinement on Jan. 19, 2021. Around this time, more folks and organizations started to join the campaign and we decided to rename the group the Free Prakash Alliance. With more people power, the alliance was able to hold more rallies and speak outs during Prakash’s court dates.

Once Prakash put his body on the line, leading a march from the courthouse steps across Queens Boulevard to the DA Melinda Katz’s office to confront her and demand she drop all charges against him. Holder banned him from speaking at his own rallies in response and threatened to send him back to Rikers.

Katz considers herself to be a progressive and works closely with Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network to reframe her office as social justice oriented, instead of the genocidal truth. The reality is that she stands to lose a lot if Prakash is exonerated, because that would open the door to civil lawsuits where settlements can be in the millions.

Prakash has been on home confinement now for 15 months and counting as Katz continues to drag the case out. Prakash’s partner, Familia, brought their son Kayden into the world this past December.

All Prakash really wants is to go on with his life and be free to do the things he missed out on as a teenager, like visiting an amusement park, or even walking down to the ocean that waits for him at the end of his block, even though he can’t go there now.

Every day, the stress of having his life at the mercy of the most horrifying system imaginable takes its toll. Prakash, who is intellectually disabled, also suffers from intense PTSD. He knew even before he was bailed out that the trauma he’s experienced would be within him forever.

But still, each day he fights, each day he tries to motivate others to fight with him. Each day he survives.

As the trial approaches, community support for Prakash is still relatively thin and one question looms large. Will there really be no peace where there is no justice?

But there are two things that are certain. Prakash did not do this crime. No DNA evidence ties him to the scene, only faulty ear witness testimony and the false confession. Prakash could have been out of prison by now if he accepted a plea; but he turned it down. The other thing that is certain is that Prakash deserves freedom – all of it.

In captivity since he was just 15, Prakash has had to face battles the bravest among us would run away from. He’s been told by everyone that this fight is impossible, just like enslaved people were told they could never free themselves. But he’s always done what abolitionists have always done, which is to dream and not give up on those dreams, believing that freedom isn’t just possible, but necessary.

Joergen Ostensen is a journalist and prison abolitionist committed to the liberation of all people. They can be reached at joergen.ostensen@gmail.com.