‘Come back to the raft ag’in, Huck honey!’

by Cecil Brown

I watched Dexter at bat. I had not seen him playing baseball after the epidemic. I watched him as he struck out. He is tall for his age, 11, and I’ve seen him hit solid balls out of the park. But he seems not at all upset that he struck out.

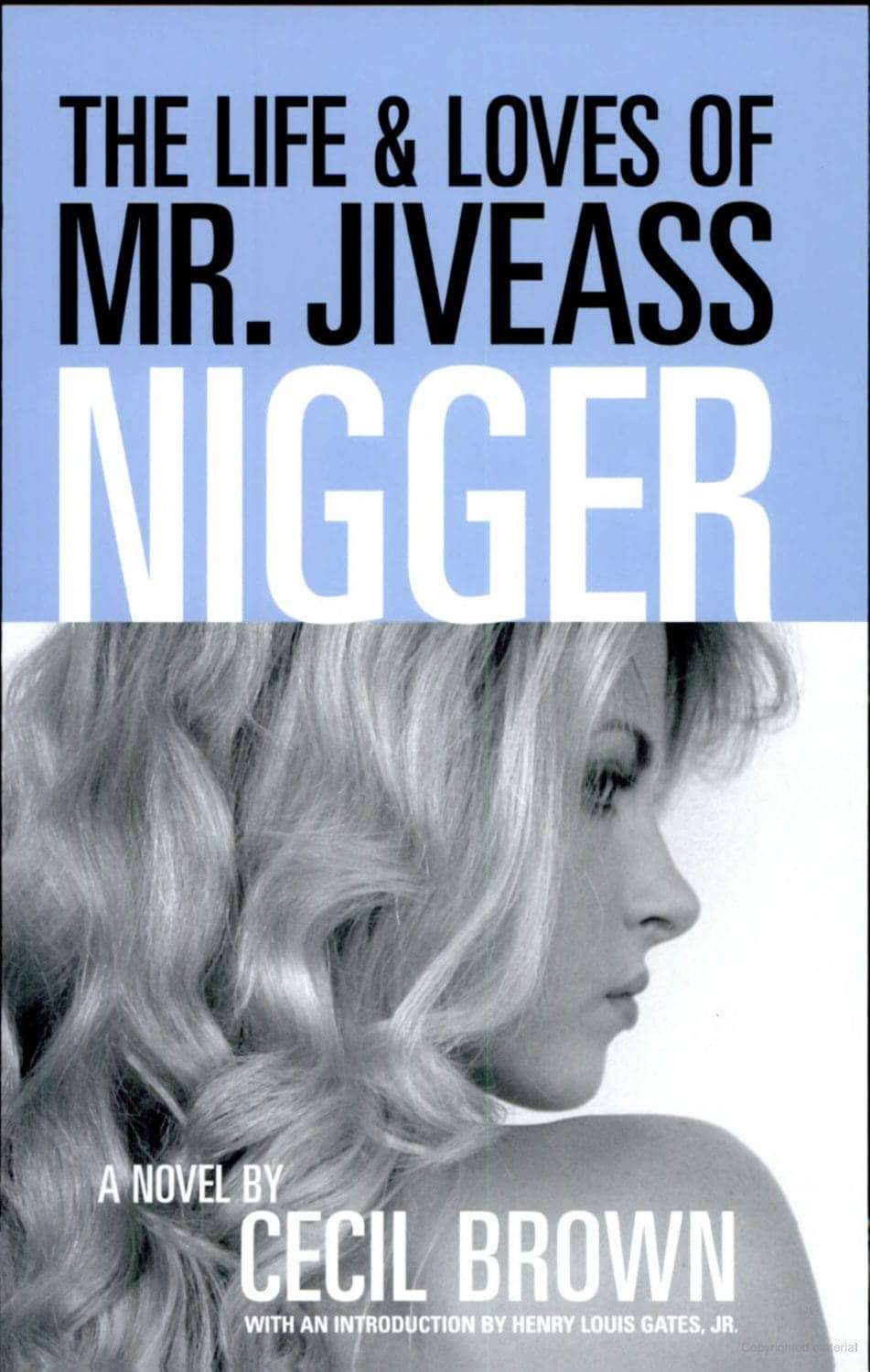

We went to have lunch at Treasure Island. I picked up the newspaper and saw that Johnny Depp was in the news. This time he was suing his ex-wife. I laughed and said to Jessica, his mother, that back in the day, Johnny had said some good things about my first novel “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger.”

Dexter, who was at the other side of the table, leaped up and ran over to me. “What did Johnny Depp say about your book?”

I was surprised. I didn’t even imagine that he was listening to us. I was surprised, too, because on the baseball field he was bored, but now just hearing that Johnny had read one of my books I could literally see a light going off in his 11-year-old head.

Half an hour later, he came back over and asked me if he could take a photograph of me for my next book. I was very impressed and I immediately agreed.

A little bit later, he again wanted to know what Johnny Depp had said about my book. Notice he never asked me what my book was about but only what Johnny Depp thought about it.

I enjoyed seeing how Dexter was processing the idea of a famous idol actually reading a book that I had written. As I watched him out of the corner of my eye, I tried to remember what it was that Depp had asked about my novel.

We said goodbye. I wouldn’t see Dexter for a week or two when he was going to have a birthday, so I figured I’d have plenty of time to figure out what to tell him about Johnny Depp’s comment on my novel.

So I went online. As I did, I remembered that someone told me that Johnny Depp was a fan of my writings. In those two weeks I went on the Internet and with my memory I recounted the incident. I too wanted to know what it was that Johnny had said about my novel.

So what did Johnny Depp really say about my novel?

When Darius James arrived in Prague to visit the set of the Hughes brothers’ new horror film, “From Hell,” he paid special attention to Johnny Depp, then 38, who stars as Inspector Frederick Abberline. Jim Jarmusch, who directed him in “Dead Man,” once told me that Depp was the best actor he had ever worked with because he was conscious of where the camera was located and what it would record, and he knew how to manipulate the filmic image.

The directors of the film, the African-American brothers Albert and Allen Hughes, developed a joking relationship with Depp during the shoot, telling him: “You walk like a Black man.’’ Johnny told him that it was a compliment to be seen as a Black man by other Black men.

They also teased him about his lack of knowledge on Black literature, asking him if he’d ever read the Iceberg Slim classic, “Pimp.” He apparently admitted he had little knowledge of Iceberg Slim, master of pop culture.

But the next day he came back with a copy of my novel and asked, “Have you read Cecil Brown’s ‘The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger?’” That would set these black lite Negroes straight!

But I couldn’t tell Dexter about that. He doesn’t understand any conversations about race and certainly not about pimps with artists like Johnny Depp. Dexter’s father is African-American but his maternal line is Norwegian. Yet I could sense that he was seriously interested in my reputation. I had to be ready to answer his questions.

What’s another way to explain why Johnny Depp would be reading my novel? Hunter S. Thompson!

Johnny played Hunter S. Thompson in two of his best satiric films, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” (1998) and “Rum Diary” (2011).

He met Thompson in the offices of Rolling Stone, founded in the 1970s by Jann Wenner as a cultural center for a new movement in American journalism. This movement, called gonzo journalism, was started by Hunter S. Thompson and his fellow writers, including David Felton, John Kaye and others.

In those days, the figure everybody focused on when the topic of gonzo journalism came up was Hunter S. Thompson. But the hidden ground that surrounded this figure Hunter S. Thompson was never explored fully.

I would hang out with David Felton, a staff writer for Rolling Stone, who was doing a story on Richard Pryor. He was doing a piece on Richard Pryor and, knowing that I was Richard’s running buddy, he would come over to Berkeley and hang with us.

Felton’s story was called ”This Can’t Be Happening to Me” about Richard Pryor. The policy at Rolling Stone is that writers could publish long pieces because their readers were willing to read them.

The title of the article was based on a screenplay Richard had written in the Berkeley days – a story of his experience in Vietnam. It describes what McLuhan said in the Playboy interview.

Even though Richard and I were living in Berkeley, life was better for us than for most Blacks anywhere in America, and yet we live in a violent society. To give you one example of what I mean, we still live in the fear of white police and violence.

One day when Richard and I were sitting in the Xanadu Café on Telegraph. (It no longer exists, but the mural on the right hand side depicts what the restaurant was like back in 1970.)

I had shown him a copy of an article that I was very proud of having published. It appeared in Evergreen Review, the East Coast hip magazine published by millionaire editor Barney Rosset, which greatly impressed Richard. He had never met such Afro-American satire in the printed form of an upper class magazine. Not only was I the author of that article but I was also a professor at the great University of California down the street.

Yet while we were enjoying life and flirting with the sun-kissed waitresses, our enjoyment was suddenly shattered by the sound of an Oakland police car going down Telegraph. We watched the Blue Meanies’ cop car screech to a halt and two cops began to fire bullets into the car as the door flew open.

A Black man staggered from the car and ran into the Mediterranean Cafe. He fell between two chairs, dead in a halo of his own blood.

When I turned around, I saw Richard’s look. He said it reminded him of Vietnam.

He called that particular screenplay he was working on “I can’t believe this is happening to me!” These were the words that were spoken by the narrator as he lay in his coffin after being shipped back from being murdered in Vietnam.

- * * * * *

When I came out of my meeting with Jann Wenner, there was a party going on and David introduced me to Hunter Thompson.

This new environment young white Americans were responding to was best explained by Professor Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian who was interviewed in Playboy magazine in 1969. In order to understand it, we have to listen to McLuhan’s wise philosophy and analysis. It was widely read.

It suggested that we were living in a new electronic environment so fast that it would change man’s relationship to himself. Refusing to admit to the new change, people refused to change.

In the long interview, McLuhan talked about the state of everything from drugs to the sexual explosion to the rise of nationalism within the Black Panther Party. He described a society in turmoil. By the end of the 1960s, America had witnessed the assassinations of the Kennedys, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King and the escalating of the Vietnam War.

McLuhan said that the state of affairs was so bad because we were living in a new environment, an electronic environment that was invisible to us.

* * * * *

Hunter Thompson represented the generation after the counterculture, after the Beats and the Summer of Love. Norman Mailer called them the “White Negroes” and praised them for their rejection of white racist society.

Mailer was admired by younger white journalists like Hunter Thompson. Hunter had just published his book on the Hell’s Angels, where he had spent.a year living with them. The book was a huge success and mainly because Hunter was an active participant in the making of the story.

Although he didn’t call the book gonzo, the kernel of the concept was hidden away in his admission that he had violent tendencies like many of the Hells Angels. He admitted that he was addicted to beating people up and getting beat up himself. By the time he was introduced to me in the office of the Rolling Stone, he had renamed his technique and called it gonzo.

David Felton set up an interview with me and Jann Wenner, the editor and co-producer. I strolled into his office and took over. I had just gotten a good introduction from David as one of the people who really knew Richard Pryor.

Jann was behind his desk, a white man who had dropped out of Berkeley and started his own magazine. Before that, he had been an editor at Ramparts Magazine, which supported the Black Panther Party.

Jan Wenner’s magazine was a reaction and response to the changing social environment. The rock ‘n’ roll generation had demanded their own magazine.

A few years earlier I had interviewed Eldridge Cleaver and he probably took me to the office of Ramparts, where he had a desk. After a few years of working for Ramparts, Jann Wenner was out of a job and came up with the idea of the Rolling Stone magazine devoted to young white college students who love rock ‘n’ roll.

McLuhan called this new change from the typographical world of print to the electronic world of the computer the “zombie stance of the technological idiot.” We shared this virus and were fighting it.

In response to this new numbing, Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner was about finding an anti-environment environment to replace the old environment.

When I walked into his office he said, “What do you want to write about for Rolling Stone?’

I said, “Tennessee Willams!”

He just looked at me and I explained that my interviewing Tennessee Williams was the equivalent to Rolling Stone interviewing Richard Pryor. He liked the idea and nodded.

“Do you know Tennessee Williams?” Jann asked me.

“No,” I said, “But he knows me!”

There was some truth to this too. I had actually met Tennessee in his dressing room; he looked over the little audience and said to me, “I know you!”

“Do you know where Tennessee Williams lives?” he laughed.

“New Orleans?” I was guessing.

But Jann was already willing to send me down to New Orleans fumbling like a blind man for Tennessee Williams house!

Which is what happened. When I flew down to New Orleans, I still did not have the exact address for Tennessee Williams when I arrived in New Orleans. But taking a risk was a scent of blood for Jann.

In New Orleans, I found a library and the librarian turned out to be a fan of Tennessee Williams and knew exactly the house that Tennessee Williams lived in in the Garden District.

I was excited as I knocked on the door and a Mexican man answered. “Yes, of course,” he said, “this is the house of Tennessee Williams, but he is not here. He is in his other house.” “Where is that?” I asked. “Oh, that’s in Key West.”

When I responded to the Rolling Stone that Tennessee Williams was not even in New Orleans but in Key West, Florida, I expected to turn around and fly back to San Francisco.

“Oh no, oh no, that’s just fine,” Jann exclaimed, “We’ll book you a flight to Key West and a hotel. Take good notes!”

I remember looking down from the small plane as we flew to Key West and feeling the thrill of adventure, finding myself in the midst of an exciting journey.

I’m not sure how I got the exact address to this location, but I knocked on the door and there was the famous man, the great playwright Tennessee Williams.

That is when all of the fun began. Tom McGuane, was making a film from his novel “Ninety-Two In the Shade.” It was starring Peter Fonda. The film was shooting and was released the next year, 1975.

The cast and crew were all staying in my hotel. Another writer of the crew was Jim Harrison from Montana, a poet and also a diplomat. He introduced me all around. When I arrived in Key West to interview Tennessee Williams, I had stumbled on the setting for this group. People I had met in Los Angeles and San Francisco were here, too.

At the end of a day interviewing Tennessee, I would meet with the gang and the real adventure would begin. I would find a lively gang of writers, actors and a photographer, Annie Leibovitz, who was sent down to photograph Tennessee.

This group of writers didn’t have a name but they struggled with identity and art. They were the hidden ground to the figures of Johnny Depp and Hunter Thompson. They were lovers of drinking hard liquor and they loved guns. They were romantics. Then for some reason, many of them self-destructed, several committing suicide.

They shared a myth which assured them they were on the right path to beat you to it. They had the courage to go all the way. Buy the ticket; take the ride.

Nearly all of them killed themselves by blowing their brains out with a magnum: Richard Branigan, Hunter S. Thompson, Don Carpenter and others.

* * * * *

Who is the real Hunter S. Thompson? and who was the gonzo journalist? Around the top of the ‘70s, I was hired to write a film for my friend, Richard Pryor. Part of my contract included an apartment in the Sunset Marquee Hotel, the heart of West Hollywood just off Sunset.

I would work on the script in the morning and then head down to the bar around lunch time. I quickly realized that the hotel was full of writers working on scripts that would shape the new cultures.

They were fashioning the cinematic version of “Hunter, the Maniac.” It was at the bar that I met John Kaye, who was writing a film about Hunter Thompson, called “Where the Buffalo Roam,” introducing a new genre of film making.

Hunter S. Thompson, “The Archetype,” who was an avatar for Hunter, the novelist, had at least three films devoted to his biographical life. This was the first movie based on the gonzo journalist archetype.

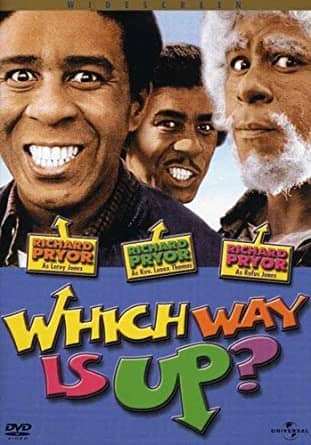

Jimmy Buffet, another great white artist, was a musician who hung out with filmmakers and writers and other artists who were not musicians. These writers were special when I was working on the script which came to be “Which Way Is Up?”

John Kaye, who lived in Mill Valley, took me to a bar to meet Hunter S. Thompson. This event had to have taken place around 1980, because John’s film, “Where the Buffalo Roam,” had just come out. This was the first film to celebrate the gonzo archetype. I had just published the cover story for Mother Jones on Richard Pryor entitled “Blacks on the Hollywood Plantation.”

I had also quoted John Kaye in that article on the making of “Where the Buffalo Roam” (1980), starring Bill Murray.

Bill Murray was a kind of avatar for the real writer Hunter S. Thompson. He learned to “make believe” that he was Hunter the writer as he impersonated him.

When Johnny Depp’s time came to play Hunter S. “Gonzo,” he was the second reincarnation, the second avatar, of the archetype of the hipster reporter.

So we were celebrating the fact that we both had films out and we were also novelists and screenwriters. He was taking me to meet Hunter S. Thompson, whose career as a journalist was the content of his “Where the Buffalo Roam” film.

Who was Hunter S. Thompson, the writer?

A year later, on Feb. 20, 2005, Hunter S. Thompson, the famed “gonzo” journalist best known for “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” – a supposedly nonfiction account riddled with drug-and-alcohol-fueled flights of fantasy and made into a movie starring Johnny Depp – shot himself through the head. He was 67.

And both, finally, were trapped by the persona they created. In the 1960s and 1970s, Thompson created “Hunter S. Thompson,” a booze-guzzling, drug-taking lunatic ready to do anything for a kick. In the 1980s and 1990s, Gray created “Spalding Gray,” a man who eviscerated himself emotionally and psychologically in front of an audience. In time, with fame and notoriety, both men became the persona they created, and each played out that persona to the end.

Thompson was from Louisville, Kentucky, born into a family at the lower rim of middle-class. While he was in his teens, his father died, after which his mother became an alcoholic, lending a bit of Southern Gothic to his upbringing.

Getting in trouble with the law when he was 18, Thompson was given the choice between jail time and the military. He chose the latter. He was eventually identified as someone who had trouble taking orders, and he was mustered out of the air force honorably, but early.

Thompson’s literary world was also filled with anxiety, but he rarely if ever blamed himself. He tended to turn his anger outward, disgusted at the “hideous” way he was treated. His attitude was that the world was “savage” and “monstrous” (two of his favorite words), and that the roadblocks put in his way were the fault of the “swine” who were out to get him.

“Fear” and “loathing,” naturally, were also keywords in Thompson’s universe. From the paranoid point of view he perfected, it’s all fear and loathing. The world is to be feared and loathed because a free man will always bump into institutions and individuals determined to keep him from doing what he wants to do when he wants to do it.

In his book “Love and Death in the American Novel,” literary critic Leslie Fiedler pointed out that America’s classic novels, like “Moby Dick” and “Huckleberry Finn,” consist of a white protagonist escaping civilization with a man who is nonwhite. In these works, as well as the novels of James Fennimore Cooper, there is a homoerotic connection (neither stated nor acted upon) between the two male protagonists as they go into the unknown – whether it’s the Mississippi River, the open sea or the American West.

Whatever one thinks of Fiedler’s thesis, there’s no question that “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” falls squarely into that narrative pattern. The only relationship in the book is between “Raoul Duke,” Thompson’s alter-ego, and his “300-pound Samoan attorney.” Throughout the book, the writer and his attorney engage in macho buddy challenges involving massive ingestion of drugs and liquor, threatening behavior, reckless driving, property destruction and laughing at the straight world (a district attorneys’ convention).

In Fiedler’s theory, the keywords are “escaping civilization.” What the two protagonists escape from is adult responsibility: the world of wives, children and family obligations.

The fact that Thompson effortlessly blends the steady stream of factual information with hallucinations, theatrics and clear-cut fabulation cannot be validated even by New Journalistic experiments with language and content. Ironically, in letters to his editor, Jim Silberman, Thompson did confess that the narcotic feel of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” was a pure fabrication. He did not write the book while intoxicated with unbelievable quantities of ether, mescaline, cocaine, acid and various pills.

On the contrary, he structured the book quite lucidly to make it look like an unedited and immediate record of authentic incidents. This is why, at the end of the day, his Las Vegas book is both a novel and a reportage, a product of the imagination but anchored in actual, if somewhat distorted, experiences.

Later, Hunter would use such a gun to end his life. As he recorded his death scene, he wrote in a suicide note, “You buy the ticket, take the ride.”

Hunter Thompson gave his followers like Johnny Depp a taste of the tribal life that Marshall McLuhan had described.

* * * * *

Who is the real Hunter Thompson and who was the gonzo journalist?

Who is Hunter Thompson? The author of the novel “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” he had a hard time getting published, so he tried to get assignments from Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated.

Although not recognized much as an antecedent to gonzo journalism, Terry Southern was a brilliant prototype to a type of genre that is a parody on academic scholarly articles and journalism both.

In the most celebrated form of this genre is Terry Southern’s “Twirling at Ole Miss.” Esquire Magazine commissioned Southern to travel to the University of Mississippi to cover the Dixie National Baton Twirling Institute.

Although he arrived in October to cover the baton twirling event, he arrived in Oxford, Mississippi, the day after William Faulkner’s funeral in July 1962 and discovered a town steeped in the segregated values of the “Old South.” The opulence of the Dixie National Baton Twirling Institute cast a shadow upon the African-American sharecroppers driving mule-pulled carts through town.

Following this New Journalism, Hunter covered the motorcycle race in Las Vegas.

These “assignments” were a genre in themselves. It was a form that gave Thomas the opportunity to create an over-the-top reporter, have a gag writer and have a political commentator always.

Another big event that had stamped his face on the ‘60s was the ‘68 Democratic convention in Chicago.For this event, Esquire sent its top echelon of writers. Among the swirl were Esquire’s three correspondents – the satirist Terry Southern, “Naked Lunch” author William S. Burroughs and the French writer Jean Genet. The magazine “parachuted them in” to give an eye-witness account of the events.

“Going there wasn’t our idea,” Southern said decades later, adding: “You have no idea how wild the police were. They were totally out of control. I mean, it was a police riot, that’s what it was.” The writer would later be called to testify in the conspiracy trial of the so-called Chicago Seven.

Southern captured the chaos in a subsequent article titled “Grooving in Chi.”

As it happened, Johnny was a part of that new environment.

Like Terry Southern, Thompson turned to the movies also.

Southern became the great screenplay writer of “Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” Dr. Strangelove was a parable of the ending of the 1960s, with the line, “We blew it, didn’t we?” According to some critics, “Easy Rider” was a parable of that ending: The motorcycle blows up. What an image of America.

The famous meeting between Johnny Depp and Hunter S. Thompson took place in 1994 in the back of the cafe. They exchanged greetings, discovering they were both from Kentucky. This released a ton of repressed white male Southern folklore. He saw that Hunter had a rifle. “Do you want to shoot it?”

Duh! They go out to shoot the rifle into a barrel of explosives.

He would visit Hunter on his ranch, The Owl Farm, and spend hours hanging with him, basically soaking up all “forms of things unknown,” learned everything he could from his guru, his friend – everything he knew about poetry, from Thompson. He read poetry with him, shot guns, did drugs, listened to him for thousands of hours, played him in a movie, played him after he died, kept his promise to shoot his ashes out of a cannon.

You didn’t need to say that to Hunter S. Thompson. He read deeply. He read the heavy dudes, like Melville and Poe and Hemingway. He read Walt Whitman, not just reading but attempting to live out the moral fiber of what he read.

Writers like Hunter Thompson were totally in with this new environmental way of thinking about their surroundings. And even though he had no academic expectation, Johnny looked upon Thompson as his college professor.

But if Thompson was a college professor, he was one weird college professor. Johnny found out when he first met Hunter in Woody Tavern, in Colorado. Hunter enters the bar with a cattle prod and an electric stick, crying out, “Get out my way, you bastards!”

For his part, Thompson was a unique, committed rebel. Unlike Johnny, who had dropped out of high school and never darkened the door of a college classroom, Thompson had gone to the best universities, graduated from Columbia University. He was not just some schmuck who was “well read.” He had read deeply. Alexander Pope had written a warning to shallow people. “Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring.”

During the ‘60s, the most popular book that an aspiring writer like Hunter S. would read, and did read, was Leslie Fiedler’s “Love and Death in the American Novel.” Fiedler was the first critic who advocated that the classic novels like “Moby Dick: The White Whale” and “Huckleberry Finn” were really about the horrors of slavery.

Hunter S. Thompson took the idea of the damaged American soul very seriously.

Why was the white man seriously damaged? If you had to ask a question like that you were coming along in the age of TV. The answer of course is that whites were in serious danger of losing their souls because they had exterminated the Native American and enslaved the Black man.

They read Melville and Twain. Both of these writers cast plots wide enough to include the exploitation of Native Americans and enslaved Black people.

It starts with Mark Twain in 1871. Twain was in his hotel waiting for his breakfast in the course of a 53-lecture tour, taking him to 76 towns.

When the door opened, 7-year-old William Evans was there to deliver his room service breakfast. But instead of just delivering the meal, he told the author that his father “used to git drunk, but dat was befo’ I was big. … Jis’ takes one sip in de mawnin’ now.”

He shared the local knowledge that “dey’s been cats drownded in dat water dat’s in yo’ pitcher.” “Some folks says dis town would be considerable bigger if it wa’n’t on accounts of so much lan’ all roun’ it dat ain’t got no houses on it,” he added.

The glow of Jimmy’s talk stayed with him, as he reported two weeks later when learning that his wife Olivia and a neighbor had both liked the sketch, which he had sent her for safekeeping. Young Evans charmed Clemens when delivering a room-service meal. No sooner had the young boy left the room but Twain had grabbed his quill and begun to write.

Mark Twain was so impressed by the young African-American’s speech that he immediately wrote down the entire conversation, sent it to his wife and later published it in 1871.

He turned the sketch into a model for Huckleberry Finn, thus incorporating African-American speech after observing such humanity and human emotions in such a young person.

What so charmed Twain – the openness, the honesty and wonderful play with speech – so impressed Hemingway, and then Thompson and all the writers and actors and musicians. Huck’s voice meant something to them – and often to them alone.

Hemingway for these writers was the great classic American writer. The central figure to Thompson, Hemingway reflected the hidden background of the American classic prototype of what it took to produce a good man.

For one thing, you had to be on the same emotional side as the Black man. Even though Huck is a white boy, you can tell by the attitude that to the people around him he is really a Black figure, at one with a physiography of a Black boy.

If you read deeply, you could see that Twain was describing Huck as a Black boy and that this was modeled on the real Williams Evans, that Black boy.

His appearance is described in “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.” Huck wears the clothes of full-grown men which he probably received as charity. As Twain describes him, “He was fluttering with rags.”

He has a torn, broken hat and his trousers are supported with only one suspender. Even Tom Sawyer, the St. Petersburg hamlet boys’ leader, sees him as “the banished romantic.”

As Twain tells the story, Huck and Jim on the Mississippi represented a new environment. Some critics claimed that the environment was an escape from the control of the female household, the world. For the Black men, ex-slaves, “freedom” meant “going to the territory!” – goin’ out West.

Even the location of “Huckleberry Finn” appealed to writers who would buy Hemingway. Tom McQuane wrote a script about the Missouri Breaks, starring Marlon Brando. Writers like Thompson believed in strong support of a bond between Blacks and whites. Mailer called them the “White Negroes.”

Hunter S. Thompson read the opening of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and heard the voice of the little 7-year-old William, of “Jimmy,” that Twain modeled the character on.

He taught Johnny too how to read, as they would read his own prose together. He taught Johnny how to read our American culture, the pain with pleasure.

With the aid of critics like Fiedler, Hunter S. Thompson – Falstaff teaching young prince, if you will – gave Johnny the sense of life as it is lived beyond the icy touch of the logic of literacy.

As Los Angeles book critic David Ulin put it, the true innovation in “Huckleberry Finn” was the use of “vernacular’’ expression, noting “the decision to tell the story in the voice of a country boy enabled Twain to experiment with language in a way few works of fiction had before.”

But what Ulin doesn’t say is that the particular vernacular used in the book derives from Black culture. You can draw a line directly from William Evans to Huck – Black Huck, that is.

“The other thing that makes ‘Huckleberry’ distinctive is the open discussion of race,” Ulin added. “This suggests another aspect of American culture that ‘Huckleberry Finn’ effectively challenged: our tortured relationship with race. It’s one of the miracles of the novel that a white man, born and raised in slave territory, would come out so forcefully and subtly for the human rights of Blacks. Jim is the moral center of the book, and in some sense became the progenitor of such characters.”

Ulin quotes Hemingway: “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn,’” Ernest Hemingway famously declared in 1935. “It’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

“What does it mean to call ‘Huckleberry Finn’ a great book, and Twain a quintessential American voice?” Ulin asks. “Such praise means nothing if we can’t feel it, if we can’t get inside the language, the world view, if we can’t experience it as living literature, something that transcends its time.”

Kurt Vonnegut once suggested about the creation of “Huckleberry Finn,” Twain simply “flabbergasted himself by writing a novel as comically profound as the masterpiece ‘Don Quixote’ … How the heck did he do that?”

Professor Leslie Fiedler attempted to answer Vonnegut’s question. “Love and Death in the American Novel,” published in 1960, was probably Fiedler’s best-known book. It analyzed the work of Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway and other writers. Mr. Fiedler contended that American literature was defined by alienation, the exclusion of women and homoerotic feelings between men, notably between Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and the slave Jim.

Mr. Fiedler’s still-celebrated 1948 essay “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!” revealed his bent for radical thinking. In it, he examined male bonding in 19th-century American literature.

Already at the start of his career, Hunter S. Thompson would attempt to live up to a certain ideal of a lone macho writer through consuming copious amounts of Wild Turkey and drugs, sleeping around and instigating bar fights and run-ins with the law.

Apart from these typical macho trappings, his very writing was an attempt to catch up with those giant men who had come before him.

Years after the publication of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream,” he would brag with unabashed self-aggrandizement that it is as good as “The Great Gatsby” and better than “The Sun Also Rises.” Raoul Duke enters the chaos of Las Vegas to bear witness to its decadence and to record its numbing madness. Neither is able to turn away and leave the crumbling gilded reality before it is too late.

With Hemingway, Thompson went all the way – including killing himself the way Papa Hemingway did.

Thompson modeled his characters on Twain. He didn’t love Twain like he did Melville, who was dark. He loved Twain and understood “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” as satire about slavery.

Seizing on the satire of a White Huck and Black Jim floating on the Big Mississippi, Hunter was inspired by the myth of the true American who seeks freedom. He called his novel, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” and added as a subtitle, “A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.”

Hunter knew and he taught Johnny that the artist was somebody who stirred things up by “putting” the previous environment on. The artist, McLuhan was writing at that time, “is someone who is putting on the culture.” The artist is always an outlaw, he goes on to say, “because the ordinary perception is boring to him.”

Thompson was not just satisfied to know the good literature. He wanted to make it, to do it.

“Weird?” He once quipped. “Johnny, it ain’t never too weird.”

More than any of the others who followed Hunter, Johnny took the ride the furthest.

Like his mentor and model Hunter, Johnny read deeply into the Pierian Spring. He too culled a style of the tribal man, using it as the mask in “Dead Man.” He had a new mask and an appropriate look for every single film character he played. He always kept his eye on that sacred bond of American culture between Black men and white men.

“(A)t precisely the time when the white younger generation is retribalizing in the electronic age,” McLuhan said in the Playboy interview in 1969, Blacks are caught between a “dying literate age” and a rising electronic society.

McLuhan would put Johnny right in there.

“Speaking of dying cultures,” McLuhan wrote, “it’s no accident that drugs first were widely used in America by the Indians and then by the Negroes, both of whom have the great cultural advantage in this transitional age of remaining close to their tribal roots. The cultural aggression of white America against Negroes and Indians is not based on skin color and belief in racial superiority, whatever ideological clothing may be used to rationalize it, but on the white man’s inchoate awareness that the Negro and Indian — as men with deep roots in the resonating echo chamber of the discontinuous, interrelated tribal world — are actually psychically and socially superior to the fragmented, alienated and dissociated man of Western civilization. Such a recognition, which stabs at the heart of the white man’s entire social value system, inevitably generates violence and genocide. It has been the sad fate of the Negro and the Indian to be tribal men in a fragmented culture — men born ahead of rather than behind their time. …

“I mean that at precisely the time when the white younger generation is retribalizing and generalizing, the Negro and the Indian are under tremendous social and economic pressure to go in the opposite direction … (T)hey are now impelled to acquire literacy as a prerequisite to employment in the old mechanical service environment of hardware, rather than adapt themselves to the new tribal environment of software, or electric (electronic) information, as the middle-class white young are doing.”

Looking at the young white artists, writers and actors like Johnny and Hunter, I understand what he means.

Asked what will happen to Blacks if they don’t adapt to these pressures, McLuhan said “extermination.’’

Today, some 40 years later, we see McLuhan’s fear. Days ago a young 18-year-old white man live broadcast himself walking around in a Buffalo food market executing Blacks, copying another live performance of murder he had downloaded a few years ago.

The retribalization

“Huckleberry Finn,” a satire about Reconstruction, was also a parable of the American dream gone haywire.

The film “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” is a satire of the present consumer culture.

Johnny Depp, who played the odd ball journalist in the film, is Huck Finn, with the Negro Jim, the slave he hopes to free, on a lifeboat speeding down the Mississippi of digital current. The raft is the fire-red convertible on the road to Las Vegas. The lawyer (Benicia Del Tarp) is Jim.

In the opening scene, they pick up a teenager. “Are you prejudiced?” Duke wants to know. The boy yells back, “No!” This answer makes him OK to these liberators.

Las Vegas is the center of freedom, and drugs become a metaphor for freedom. In the film, drugs are symbolic of consciousness. You really have to be an American to understand the media and its relationship to consciousness.

All of this is lost on Ian Pittman, a British writer. “It is hard to see Hunter S. Thompson,” he writes, “as much more than a footnote, a minor stylist, a figure very much of his era who became stranded when times moved on and he refused to budge.” He recognizes the hidden environment of the writer to his time.

After declaring that the film is “not so much his Götterdämmerung as his Huckleberry Finn,” he praises Thompson for “combining moral seriousness with delirious invective, amphetamine urgency and trickster humor. “

He compared the opening of Mark Twain’s preface to the “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to the opening scene of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” and praises them for being brilliant, more brilliant than any other opening in cinema literature in recent years.

In December 2001, a young African-American writer living in Berlin, Darius James, took up the story of Johnny Depp and “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger.” He was the author of a well-known Black novel, called “Negrophobia.”

When he arrived in Prague to visit the set of the Hughes brothers’ new horror film, “From Hell,” Darius paid special attention to Johnny Depp, then 38, who stars as Inspector Frederick Abberline.

So when Johnny Depp appeared on the set of the film “From Hell” in Prague with a copy of “Jiveass,” he had traveled with my spiritual creation for some time already.

By that time, Darius had graduated from the Hunter S. Thompson University of Gonzo Journalism. I was looking forward to talking to him again about Johnny.

Just as Johnny is a product of the literary and film reference system, Amber Heard is a product of the TV Child, the generation which McLuhan had so aptly titled as “overheated.”

Jack is cool; Amber is hot. Miss Ann is Miss Tang, a child on TV Age, as McLuhan would describe her.

Just as Johnny had been trained by the last of the great American novelists, Amber had missed all of this deep reading and was influenced mainly by the impact of the television generation. It should be put in the context of writers like Thompson and the hidden environment that they gave to the world.

Jim Jarmusch, who directed Johnny in “Dead Man,” once told Darius that Depp was the best actor he had ever worked with, because he was conscious where the camera was located, and what it would record, and he knew how to manipulate the filmic image.

Darius James sits down with him to separate the method from the madness.

“Johnny is one of the most talented actors of his generation,” Darius says and adds in an aside, “Is that why Johnny Depp is so damn reclusive? Depp’s concentration and focus were indeed impressive. He displayed a yogi-like ability to center himself in the moment, attune himself to his artificial environment, and project himself wholly into the reality of the scene.

When the filming ended, Darius overheard Depp and the Hughes brothers joke about blaxploitation novels – my favorite subjects – so I decided to ask Depp a few questions. Rumor had it, and it turned out to be true, that because of his early success, which dates back to “21 Jump Street,” Depp had become weary of his own commodification.

So now he avoids Hollywood altogether. He doesn’t go to movies, and he lives in the south of France with his girlfriend, singer-actress Vanessa Paradis, and their 2-year-old child, Lily-Rose.

On his way off the set, Darius asked Johnny, “Is it true you’re a fan of ‘Mr. Jiveass Nigger’?”

“Depp stopped in his tracks and,” Darius reported, “ with his head tilted to one side, turned to appraise me with a slightly owlish stare. “That’s a great fuckin’ book,” he replied. “The title alone must’ve freaked people out when it was published back in the ’60s.”

As I read this, I became excited, as it seemed to me that Mr. Depp was well familiar with the history of my novel. He knew my novel from the ‘60s! My novel was on the bestseller list in the year that it came out and it was in the genre of examining the world from the point of view of an African-American writer.

In a real sense, Johnny Depp may be reading “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger” because he may simply be doing his homework. He was – and extending Huck’s innocence and his genuine love of Black culture.

Johnny identified by reading my book, the story of the young man I called George Washington, who finds his way in a foreign land. In a sense, he too was George Washington.

In my own book, I called Jimmy by the name of the father of our country, George Washington, and I hope that Johnny identified with that too.

“There’s this other book with a great title: ‘Negrophobia.’ Do you know that one?” He was into Black literature.

“Uh, uh, yeah,” Darian stammered. “I wrote it.”

With a gesture both grand and chivalrous, suggested by his 19th-century costume of Jack the Ripper, Depp dropped to one knee and, with a flourish of his arm, extended the palm of his right hand. “I bow to you, sir!” he exclaimed. “That’s one of my favorite books!”

Like “Jiveass Nigger,” Mr. Darius novel, “Negrophobia,” is about race and Blackness from yet another Black man’s perspective. These were novels that Johnny Depp identified with and respected.

Later that evening, Darius met Depp, Allen and Albert Hughes, and other members of the cast for dinner. After I had researched Depp for the previous few days, I was especially interested in what Darius had hidden in his interview.

Because Depp had lived the life of a pariah in Los Angeles, it was interesting to hear his description of his life as a poor actor. When he picked up the guitar, it was as much to nurse himself and stay alive.

That evening in Prague, Darius described Depp as “looking like an exhausted rock musician who’s spent one too many nights in the tour bus while promoting an album unsupported by his record label.” Ballpoint-ink drawings covered the white surface of his looped painter’s pants, and he was wearing a Rage Against the Machine T-shirt with a blown-up image of Che Guevara. Depp digs Che, as well as the Black Panthers, Basquiat, Mingus and Coltrane – and the Hamburgler.

The next morning, they all sat down and had breakfast and talked. Thelonious Monk was playing on the box, and Depp, I discovered, is a Boss Cat Daddy original. This setting made sense to me.

His definition of being an artist fits so well with what Marshall McLuhan said that ours was an electric environment. The artist is looking for what is in the environment that we do not see and do not feel. Darius asked him, why did he make the film about a man like Jack the Ripper.

“I’ve always been attracted to things of a darker nature,” Johnny rejoined. That made sense to me after he had been through living with Hunter S. Thompson.

“I remember getting in trouble in school for drawing pictures of Frankenstein, so a movie about Jack the Ripper was right up my alley. I was a big fan of the Hughes brothers’ work. When they came to me with ‘From Hell,’ I jumped on it.”

He liked the way Allen directed. “Allen gave me one of the greatest pieces of direction I’ve ever gotten. He came in on this one scene, leaned up in my ear, and said, ‘No sunshine. No sunshine,’ then walked off. Action. It was beautiful. Everything just fell into place. They’re the real deal.”

What I liked about Johnny from this interview is how much he appreciated working with the young African American filmmakers. He praised their work and said, “What they did with ‘American Pimp’ is real filmmaking. Albert’s got a camera, Allen’s got a DAT machine, and they just do their stuff. They’re not afraid of anything. It comes as close as you can to art in this field. To say, ‘I’m not afraid. Fuck the studios. Fuck this, fuck that. We do things the way we want to.’ That’s why they’re art. And that’s rare.”

In the interview, Johnny gave a glimpse of his life in Hollywood. “A while ago,” Johnny said, describing how he “took over this little apartment on Hollywood Boulevard from a friend of mine. I was dead broke, scrounging. He’d (his friend) go to Mexico all the time and leave all these pesos lying around. I’d change them at the corner check-cashing place so I could get a meal and some cigarettes. I did that until I found this Scientology place down the street. They’d give you $3 to take this weird fuckin’ test. I’d answer all kinds of strange questions under different names. I survived that way for a little while.”

“Aren’t you a fan of the Beat Generation? Weren’t you thinking about doing a biopic on Jack Kerouac at one point?”

“‘On The Road’ was my bible for years. I went back and forth in my head about it. Do you do [make a film of that book] that to that book?”

Perhaps John, like Kerouac, embraced my character George Washington. Like George, who had the same name as the father of our country, Johnny was a native son, “a Cherokee,” he says. (A lot of Blacks say that they are Cherokee.) Maybe, like Kerouac, he had walked in his reveries like a Black man.

It was not until, however, that I watched the trial between him and Amber B. that I realized there is a story about Johnny that I could tell Dexter: the reason that Depp’s lasting persona is the return to the myth of the artist as an outsider.

The early biographical story of Depp portrayed his family as poor white outsiders who moved a lot.

Like Johnny, Huck is an archetypal innocent, able to discover the “right” thing to do despite the prevailing theology and prejudiced mentality of the South of that era. An example of this is his decision to help Jim escape slavery, even though he believes he will go to Hell for it.

The white artists of the Johnny Depp aesthetic accepted the responsibility of history. They recognized themselves in Ishmael and Queequeg. Between Huck and Jim.

Johnny, like Huck, feels judged by a hypocritical society. Hollywood society, which has inherited many aspects of American Southern slave society, exploits Black people. Like these Black people, Johnny identifies with the people they exploit.

Both Huck and Johnny are seen as figures and hidden grounds. What is the hidden ground of Huck Finn? Even though he is a fictional character created by Mark Twain, he is a mask – a mask based on a real person. Mark Twain based the character of Huckleberry Finn on a young African-American age 7.

This new environment was not detectable by everybody and it calls for a new kind of artist. This new environment includes an oral tradition that has reshaped itself through the digital electronic world. We see Johnny Depp’s world of live antecedents has yielded to the more inclusive world of the archetypal tribal man.

He felt, like Jack Kerouac who wanted to be a Negro, the African-American male was an appropriate interpretation of that virus first described by Mark Twain when Jimmy – William Evans – walked through the door.

Even though journalism which was represented by the archetypal writer gonzo is finished, and even though Depp has performed his last crazy journalist gonzo role, the mythology that embraces him is finished – yet to be revived as a YouTube digital artifact.

Johnny Depp will survive because he represents a spirit of the tribal life of our revered ancestors.

He belongs to the age of American myth and legend – invisible forces.

At the end of the interview with Darius, Johnny said something that is his own, not necessarily indebted to Hunter S. Thompson.

“Do you consider yourself an inspirational figure? Because the projects you do seem intended to inspire?”

“I want to make people think,” Johnny said. “I get McDonald’s, Burger King and Kentucky Fried Chicken – all that shit. It’s easy. It’s quick. You use no brain cells to do it. But every fucking day? There’s plenty of that in the movie theaters – high-profile, big-budget escapes. You pay to get into a movie and step out of your problems for two hours. It’s escapism.”

“There are people out there trying to do something that could be considered art in film,” he said, pausing to drink that great wine, “but I’m not even convinced it’s possible, because there’s so much money involved. There’s somebody back there expecting a fucking return. It’s an investment, so it’s become tainted somehow. It’s a product, like when they talk about CDs being units instead of art. But if I’m going to do this for a living, I want to at least provoke a thought or make someone look at something, however subtle, from another perspective.”

No new anti-environment – we must draw attention to what is invisible to us so that at least we may have another perspective, as McLuhan maintained.

“There’s a dimension of empathy you bring to your characters that’s deeply affecting,” Darius said.

“I don’t know (laughs uncertainly). Last night, when we were at that restaurant, this woman asked me if I would sign an autograph. I signed a picture she had, and in return she gave me a note that said, ‘Dear Johnny, thank you for playing those poor people. Love, Irene.’

“I thought, ‘That’s weird, why’d she say that?’ So I asked my friend Keenan what she meant, and he said, ‘Think about the characters you play. They’re all these unfortunate guys who are judged harshly and get fucked around. That’s the kind of thing you’re going for.’

“She connected to the sadness,” Johnny repeats. “There is an obvious connection between all these characters. They’re all related in a weird way. I don’t know why I’m attracted to these figures, but she woke me up to something I wasn’t particularly hip to. That note meant a lot to me.”

I think Johnny is right about his reflections of these kinds of characters, the ones who are sad; but as his friend Cannon added, these unfortunate guys are judged harshly and get fucked around.

“Over the past few years, I’ve been experiencing feelings of frustration and self-loathing,” Darius admits. “But your affection for my book was a moment of inspiration.”

Johnny thanked him. “I know that feeling of self-loathing and feeling fucked up about the work. But I think that means you’re doing the right thing.”

I could tell Dexter that Johnny is an artist. Keep playing. They’re all these unfortunate guys who are judged harshly and get fucked around. He was reading my novel because he identifies with my characters, those sad people who so often are treated badly.

That would be Huck and Jim. That would be Johnny. That would be me. That might be a lot of folk. He must defend the sad people that no one really notices. They bring such joy in life to our times through performance.

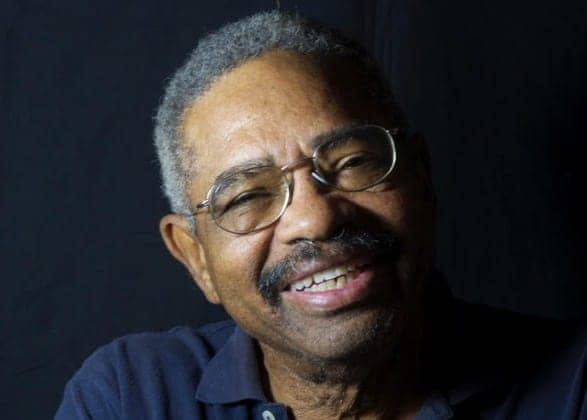

Novelist and educator Cecil Brown, UC Berkeley professor and director of the George Moses Horton Project (CESTA) at Stanford, is best known as the close friend, screenwriter and biographer of Richard Pryor and as the author of “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger,” “Stagolee Shot Billy” and most recently “Pryor Lives: How Richard Pryor Became Richard Pryor: Kiss My Rich Happy Black Ass.” Brown can be reached at browncecil8@me.com.