by Eric Hunter, SF Bay View Oakland Bureau

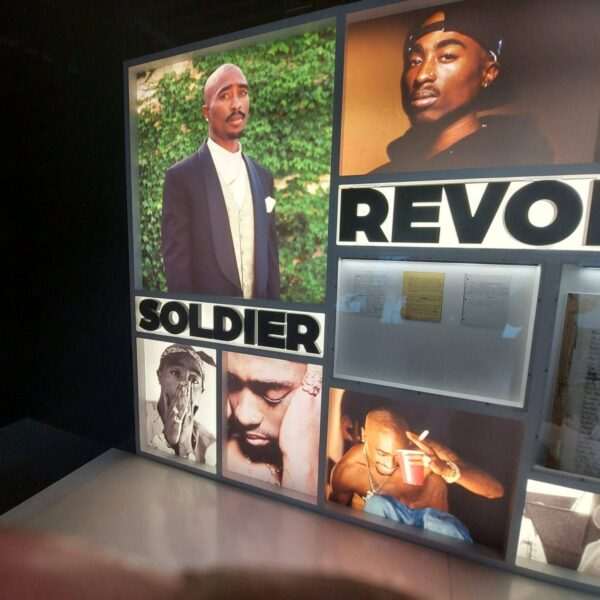

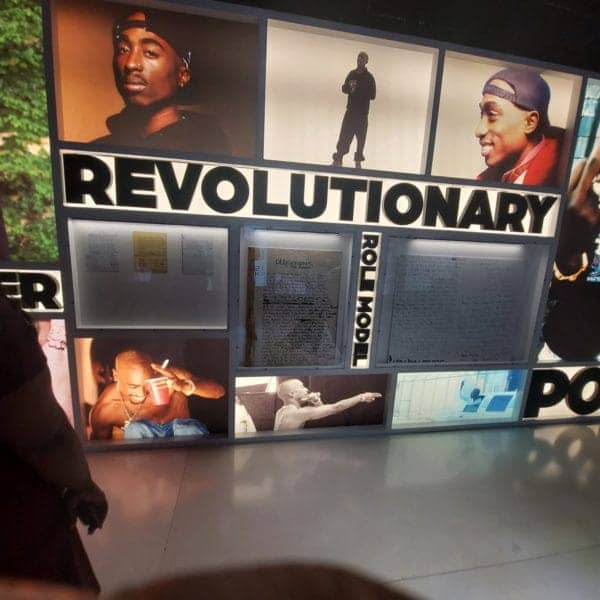

I recently got a chance to check out the “Tupac Shakur, Wake Me When I’m Free” art exhibit. This high-tech museum of hip hop culture was established by the Shakur estate and is showcased at The Canvas at L.A. Live in downtown Los Angeles, Calif. They have archived artifacts of Tupac’s art and treasured possessions that tell the story of his life on display in a very creative way.

This was an educational experience that explored the heart and mind of Tupac Shakur. There are also audio sound clips of interviews, music and more that really gave me an inside view of his upbringing and lifestyle. It also further enlightened me about his politics and philosophy.

It was very informative; I developed a deeper understanding of what inspired and motivated art and activism. It was exciting, entertaining and even emotional. It made me think, laugh, dance, almost cry, and left me in awe of the creativity and genius of Tupac Shakur.

I am so inspired and touched by what I experienced at this amazing art exhibit that I must pass this passion on to my people in hopes that it encourages other artists, writers, activists and culture creators to continue to express their enlightenment to the world.

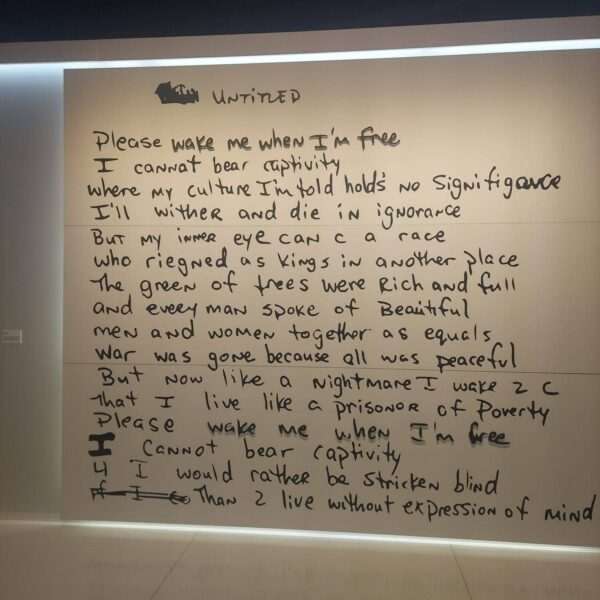

When I first entered the vicinity, I saw this all-white room with sculptures of the images that Tupac Shakur had tattooed on him. There was an untitled poem by Tupac written on the wall where the first words were: “Please Wake Me When I’m Free.” It was this poem that probably inspired the name of this exhibit.

His tattoo of the word “OUTLAW” was displayed on the wall. The term “outlaw” represents the rebellious culture of us young Black men who are living in a system that is set up for us to fail. Artwork from his tattoo that says “50 NIGGAZ” outlined with an AK-47 was on the wall.

Tupac redefined the word “nigga” by turning it into an acronym that means “Never Ignorant Getting Goals Accomplished.” This tattoo stands for his idea that it just takes 50 niggas in every major city in the world to set off a war for change.

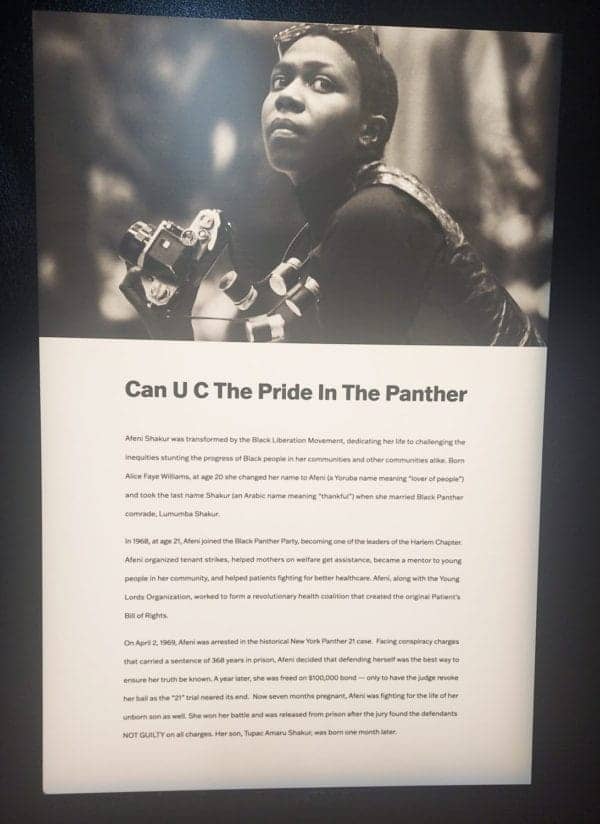

It’s very similar to the Black Panther Party’s 10-10-10 recruiting strategy. His tattoo of a Black Panther was also on display in the form of a sculpture. It was three-dimensional and appeared to be jumping out of the wall. This tattoo symbolizes his revolutionary roots as the son of a high-ranking member of the Black Panther Party named Afeni Shakur.

1831 represents the year of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion.

In the middle of the room, there was a big sculpture of Nefertiti with “2DIE4” illustrated under it. It is this tattoo that is located on his right chest where his heart is, that shows the love and honor he had for Black women. He views them as royalty.

Tupac had a tattoo on his back of a cross with Exodus 18:31 written in the center, and the iconic “laugh now” and “cry later” clowns on both sides of the cross. Exodus refers to the second book of the bible where the Israelites were freed from bondage. 1831 represents the year of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion.

The hosts of the exhibit provided us with headphones and a remote-control device to tune into the different audio clips that play in each room. The next room I entered was dark, surrounded by screens with visuals of rural terrain that looked like the Deep South. It looked like some woods that my enslaved African ancestors would have had to trek through when they ran away from the plantation.

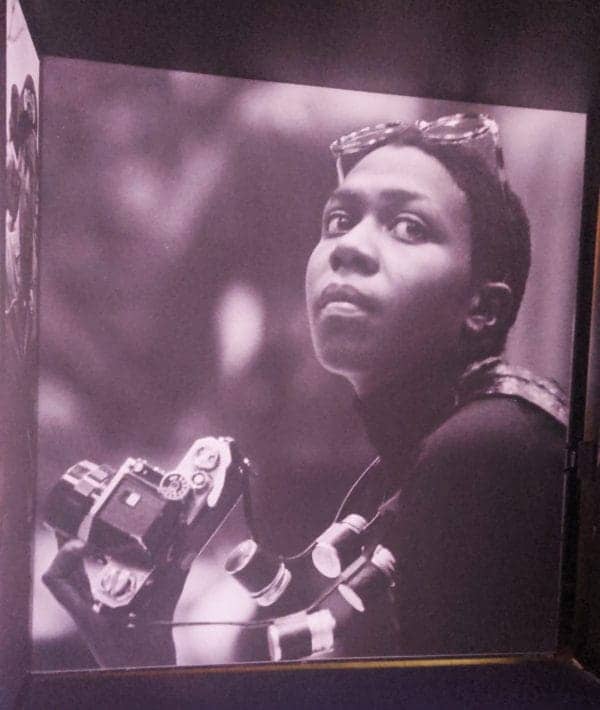

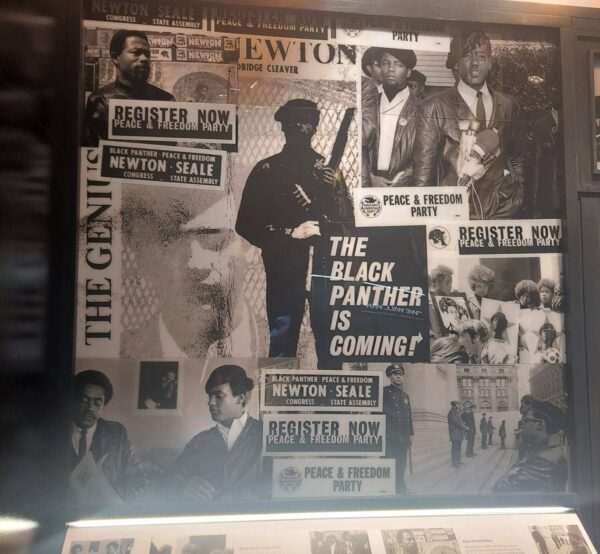

The setting was perfect for the theme, “Wake Me When I’m Free.” This was like the waiting area to chill out before the actual tour started. When the first door opened, all you could see were Black Panther Party pictures everywhere! This area was dedicated to Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur.

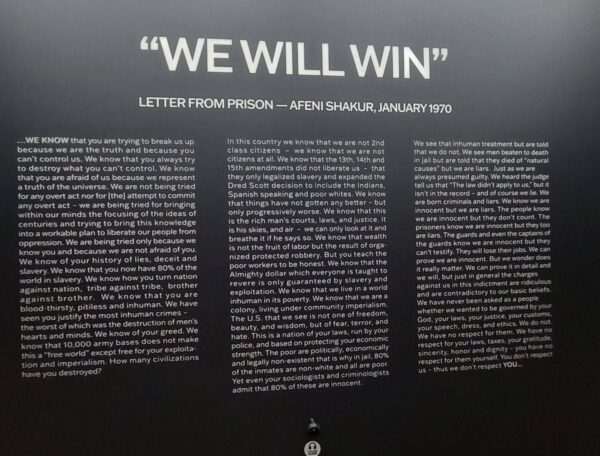

There was a collage full of clippings from the Black Panther newspaper. There was a letter that Afeni Shakur wrote in prison during the New York Panther 21 trials while she was pregnant with Tupac, called “We Will Win.” It was published in The Black Panther newspaper in January 1970.

Oakland journalist Eric Hunter visited the Tupac exhibit in downtown LA, developing a deeper understanding of what inspired and motivated Pac’s art and activism. “It was exciting, entertaining and even emotional. It made me think, laugh, dance, almost cry, and left me in awe of the creativity and genius of Tupac Shakur,” writes Eric.

Afeni, along with 20 other Black Panther Party members, was charged with conspiracy on April 2, 1969. She defended herself in court and was found not guilty on all charges. Interviews of Afeni Shakur and other fellow members of the Black Panther Party talking about why they joined the Black Panthers was playing in the earphone.

On one screen, they had rare footage of the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party at their headquarters handling business, and on another screen, they showed the Panther 21 press conference at court. Afeni Shakur’s notebook that she had in prison was on display. It had the rough draft of her autobiography that she was working on where she documented moments of her childhood, her experiences from the Panther 21 trial, and the time she spent in The Women’s House of Detention.

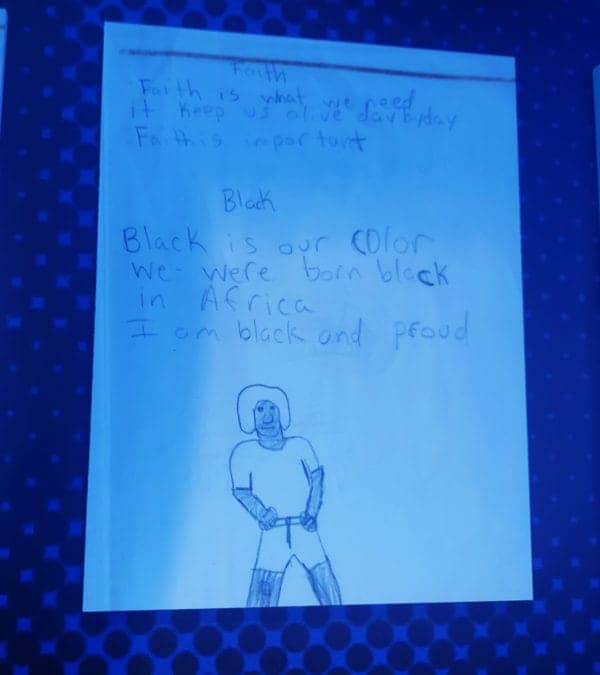

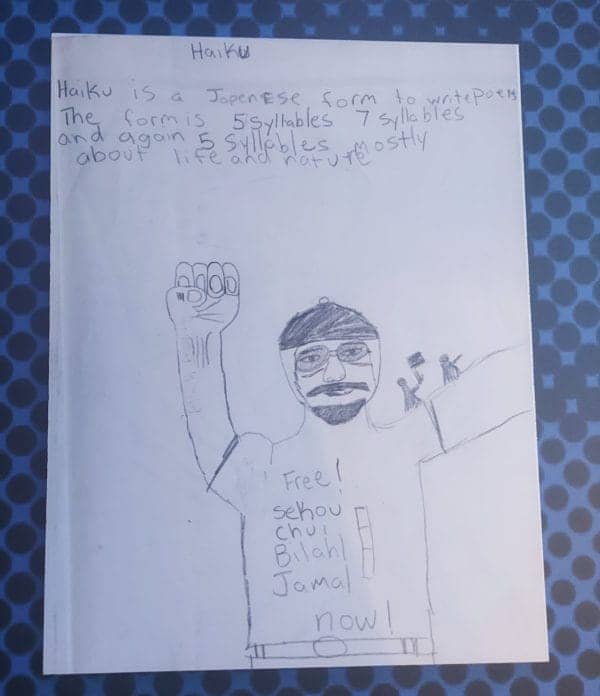

In the next room, there was the imagery of 2Pac’s childhood from pictures he drew and poems he wrote as a child. There was a row of haiku poems and letters he wrote to political prisoners and random notes including his schedule, chores, household duties and assignments. It shows that the structure in his family was very organized.

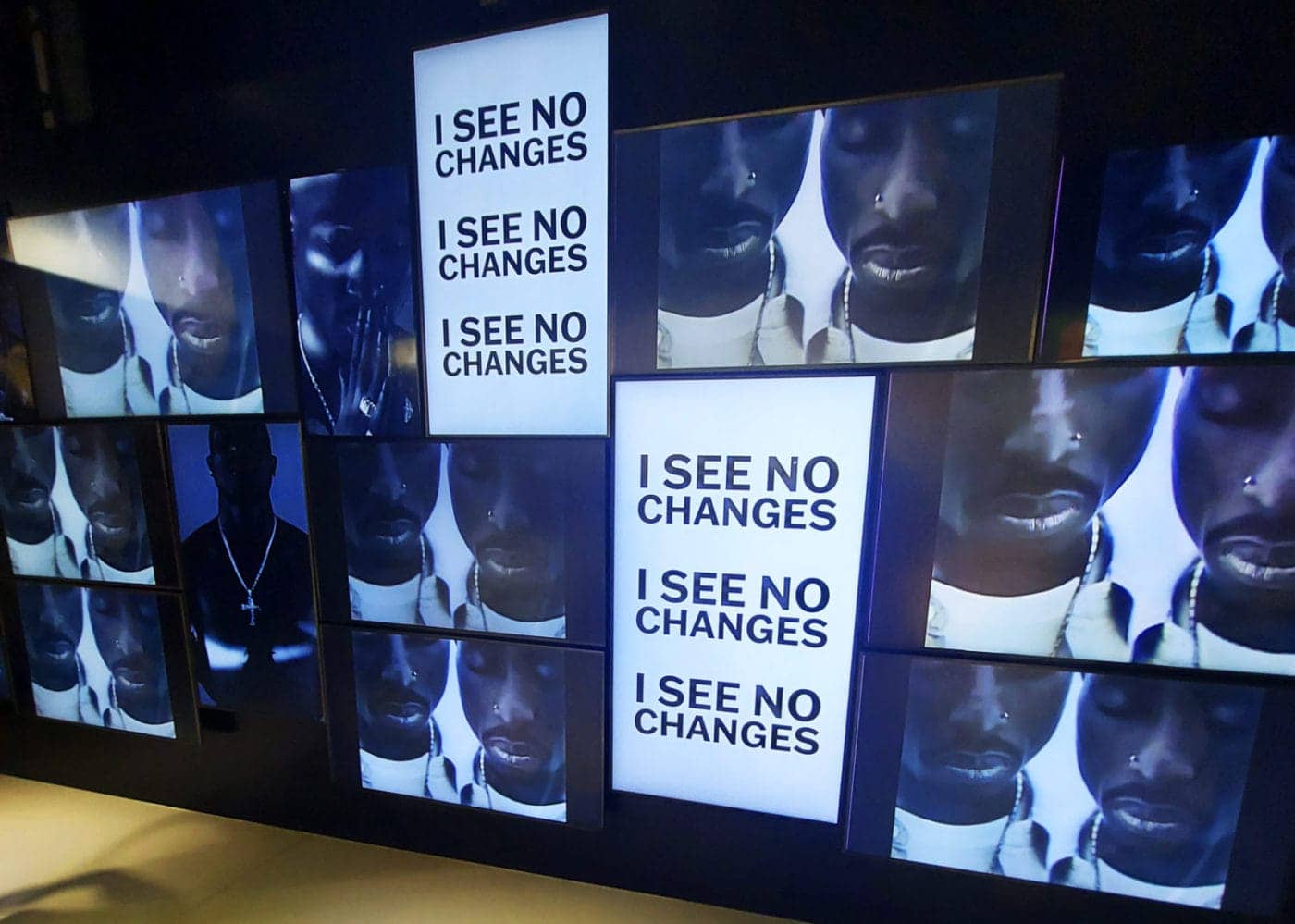

There was a stack of TVs on one side of the room with pictures of his favorite childhood movies and tv shows in one corner and on the other, there was a pile of newspapers and books that he used to read on a makeshift porch that represents the stoop he used to hang out on as a youngster. There was a collection of composition notebooks of lyrics, track lists, movie scripts and business ideas all over the wall that the Shakur estate put together.

The highlight for me was Tupac’s activist notebook for his organization New Afrikan Panther Organization. Another thing that stood out to me was Tupac’s Kwanzaa poem. I was surprised to see that he wrote a poem for the holiday of Kwanzaa, because the Black Panthers didn’t get along with the creator of Kwanzaa. There was also a wall filled with 2Pac’s movie scripts and screenplays he wrote.

I entered a section that was dedicated to his early career. The music video that 2Pac was first featured in, called “Same Song,” was played on the projector screen. Footage of other music videos and interviews was played on the TV screens.

Inside one cell was a poem written by Afeni Shakur, called “From The Pig Pen.”

In one video he’s talking about his experience living in Oakland and being brutalized by the police. They also showed the movies he played in. The quote from 2Pac: “I had no record all my life, no record, no police record until I made a record,” was written in bold letters. It made a statement about the criminalization of hip hop culture and the violation of freedom of speech in rap.

There was also artwork of his album covers and photoshoots and magazine covers. They had the movies he acted in playing on several screens. 2Pac’s creativity and work ethic is phenomenal.

I walked through a hallway that resembled a prison cell block. This represented Tupac and his Mother Afeni’s experiences of being incarcerated. Inside one cell was a poem written by Afeni Shakur, called “From The Pig Pen.” There were all kinds of documents, from 2Pac’s filed complaints to the superintendent to 2Pac’s workout regimen on each side of the hallway.

In one cell, they had the footage of 2Pac getting interviewed in prison. There were receipts for 2Pac’s grocery list and his visit schedule. They even had letters that he wrote to Chuck D of Public Enemy and Quincy Jones on the wall.

I was amazed at the number of archived documents that the Shakur estate was able to collect – it’s like they kept every personal item he owned. They had a section dedicated to 2Pac’s studio sessions at Death Row Records after his release from prison. There was a replica of the studio he recorded in and a collage of cases of his records.

I got an understanding of 2Pac’s recording process; it seems like it was very eventful. 2Pac’s wardrobe was on this display in glass cases as well as other household items, like a Maasai warrior statue. His fashion sense shows how he presents himself as royalty and the display of his art shows his connection to his African roots and culture.

I recommend that every artist check out this exhibit. I enjoyed myself and I’ve learned so much about the principles Tupac stood on. Tupac once said in an interview that he got his game from Oakland, Calif., and that’s why he claims Oakland.

He may have been born on the east coast and raised in places like Baltimore, Md., and Marin City, Calif., but he grew as a man and got his street smarts in Oakland. He was also born and raised by the Black Panther Party, an organization that started in Oakland, Calif.

Tupac’s upbringing and experiences inspired a philosophy, art and culture that the whole world has adopted. I was born and raised in Oakland, and the brain matter of the minds that manifested movements that changed the world come from the same place. This is why I feel connected to the people all over the planet, so I take this soul wherever I go and plant seeds all over the globe to grow more roses out the concrete.

Journalist Eric Hunter (E De Ref), an Oakland native, is Minister of Public Relations for the Black Riders Liberation Party and Co-Editor of African Intercommunal News Service. He writes for Black New World Media and the SF Bay View’s Oakland Bureau headed by JR Valrey. Hunter can be reached at ehunter6300@gmail.com.