by Nube Brown

Haters say, “Do the crime, do the time.” Young, New Afrikan Revolutionary Nationalist Kwame Shakur turns that on its head and into the heart of humanity as he reaches out with revolutionary love to unify, educate and transform the world around him. From behind the walls of an Indiana prison, Kwame nurtures the growth of his upcoming documentary, in solidarity with the many people he continues to inspire in the “free world,” which is currently being filmed in 11 states and 17 cities and will be available on Amazon Prime and Roku TV in 2023.

Here’s my interview with Kwame “Lil Beans” Shakur:

Nube: We’re going to be talking about your upcoming docuseries “T.H.U.G L.I.F.E: From Gangster to Growth.” I would love for you to tell us how this came about and what inspired you to do this documentary?

Kwame: Fo sho. It’s been years in the making. When we originally first started filming, we just wanted it to be about my life and the revolutionary work that my grandfather did back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, about the corruption and prosecutorial misconduct that happened on my case, and then move into chronicling my journey throughout my captivity while still pursuing my music aspirations, signing a music deal with Empire from behind the wall and then establishing an NALC (New Afrikan Liberation Collective) in Prison Lives Matter.

We started reaching out all around the country to get veteran Black Panther and BLA (Black Liberation Army) members, like Jalil Muntaqim and Baba Bilal Sunni Ali and the chiefs and founders of street tribes to do interviews about me. Nobody was turning us down, so I got to thinking: We got an opportunity here to give the people more than just a “Kwame ‘Lil Beans’ Shakur” story with all these veterans and these legends sitting down. We could give the masses a 50+ year chronicle of our struggle and our leaders, and the people who have been at the forefront fighting for our liberation.

Nube: What a vision! How do you see yourself embodying that history with your grandfather, and where you are right now?

Kwame: Yeah, so growing up, the one thing that I’m grateful for is that from 4 years up, my dad made sure that I knew who our national leaders were, going back with Malcom and the Panthers to our local leaders, like my grandfather and his comrades and what they did. Like, I never had any illusions that we were Americans or that this country and this government were set up for us. Before I ever started school, I probably knew who Malcom was before I knew about God or Jesus or any type of religion or anything. That was the upbringing that I had when it came to the historical knowledge of our People and our struggles.

So, like most people who come up from where we come from, I wasn’t able to pursue that path. My dad he was putting that knowledge on me from my grandfather, but I’m seeing my dad in the streets, I’m seeing my brothas in the streets, we’re having street wars, my mom and dad they selling dope, so that’s naturally what I gravitated to in order to survive, versus trying to create some type of revolution or liberation struggle for our People to survive.

“The mural, as well as the backside mural, is in a severe state of deterioration. We hope to refurbish this work, but funds would be needed. Conceptually, I, Spie, can take credit for gathering the imagery and thrust of the wall. Twick initiated the want to give to the community something powerful in the way of revolutionary thinking.” – Photo: Nube Brown

That knowledge of my grandfather and who my family was in Terre Haute always stuck with me, and I always kept that social and cultural knowledge with me. And now, here we are all these years later, and I feel like I’m picking up where my grandfather left off, continuing the work that he was aspiring to do.

The Community Liberation Center that he built in 1970 has since been gentrified by the city and by neocolonial agencies in support of these gentrifiers. Now I’m building a movement in my hometown to help liberate that building, to put it back into the hands of the People. And the property my grandfather and my great grandmother owned, where I grew up, we’ve now bought that land back, and that’s where we’re trying to build the New African Peoples Center.

Nube: Beautiful. Do you wanna talk about that dialectic? Talk about knowledge of self, but how asserting that knowledge of self is also what’s keeping you inside and all the other veteran Black Panther Party for Self-defense members, BLA members and Political Prisoners still enslaved.

Kwame: Yeah, absolutely. You know, we say that you can’t fight racism without trying to dismantle capitalism or vice versa. And I’m saying that you can’t be talking about fighting racism or fighitng capitalism without trying to abolish legalized slavery in these modern-day slave plantations. Because it’s all dialectical, you know what I’m saying?

These prisons took the place of chattel slavery plantations and so that’s where those veterans went that you mentioned. When they were waging the anti-colonial struggles in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it was to be free of the colonial shackles that the U.S. government put down on us fighting for our independence as a Nation to govern ourselves, which is the biggest threat to the United States empire. They don’t care that you have a movement with millions of people, they don’t care about a Civil Rights Movement or a Black Lives Matter movement, but as soon as you start talking about sovereignty and controlling your own educational, economic, political and social development, that’s when you become a threat.

Nube: I would love for you to talk about the title, “T.H.U.G L.I.F.E: From Gangster to Growth.”

Kwame: Absolutely. Both things have a significant meaning in my life. The reason the thug life concept and the acronym means so much to me is, I was raised on Tupac in my household ever since I was 5 or 6 years old. I remember my dad got “Thug Life” tattooed on his stomach when I was in elementary.

So seeing that and glamorizing that, and me writin’ Thug Life all over the house and on my school folders and on my stomach with a marker, and him tellin’ me like, “You don’t even know what the Thug Life is about. When I was little, we had an outhouse. We didn’t have no bathroom; I had to walk from the house outside to use the bathroom.” And at the time, I’m not having a revolutionary mentality, or overstanding the acronym or the concept that Tupac and Dr. Mutulu had laid down, the reason my dad was overstanding the Thug Life. I’m like, having an outhouse don’t have nothin’ to do with being a thug!

But now being older and having that revolutionary overstanding of the dialectic of thug life – The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everyone – now I can overstand what he meant and the things that he went through being an oppressed New Afrikan from birth and even having to go outside and use an outhouse to use the restroom, shaped and molded him and the decisions and choices he had to make in life and in the streets to just survive, right? I remember being like, what the fuck is he talkin’ about?! I didn’t even overstand what Pac and Dr. Mutulu meant with Thug Life, right, because my brain wasn’t revolutionary.

With Thug Life, Dr. Mutulu (Shakur) had originally created this concept while he was inside the federal penitentiary. And when he brought it, he was trying to establish a code of conduct for our street organizations. When he brought it to Tupac, and then our late comrade Sanyika Shakur, formerly known as Monster Kody, got involved, their objective was to bring this concept to and politicize the street organizations and try to get back to the root and the foundations of where our Kings and our Chiefs and our Founders and Chairmen originally had envisioned for these street tribes to go when they started in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Like Tookie with the Crips and my Chairman Larry Hoover with the GDs (Gangster Disciples), and Brother Chief Malik (Jeff Fort) with the Black P-Stones, none of these organizations started to destroy our community. They were never meant for our People to sell dope, to go rob; none of them were promoting this. So they started these political organizations to try to take control of our educational, economic, political and social affairs in our community. Pac called it Thug Life; he gave it the acronym, The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everyone.

As much as I love my street tribe since I was 9 years old, now that I have a revolutionary mentality and I overstand the core issues of our oppression as a people on these shores, I overstand what his vision really is for us.

When it comes to “From Gangster to Growth,” I’ve been a member of GDN (Growth and Development Nation), under the vision of Larry Hoover since 1999, since I was 9 years old. And, like most members of GDN, I started out under the old concept of GD, meaning Gangster Disciples. As I’ve transitioned and developed a revolutionary mentality, I overstand the new concept that Larry Hoover put down for us of Growth and Development, that we now operate on a concept of educational, economic, political, social development organization and unity.

And as much as I love my street tribe since I was 9 years old, now that I have a revolutionary mentality and I overstand the core issues of our oppression as a people on these shores, I overstand what his vision really is for us. So, it wasn’t hard for me to make that positive transition from gangster to growth. And a lot of the people who sat down for this documentary also come from that path of the criminal mentality, of the so-called criminal mentality and that gangsta mentality, and now they are representations of that growth, of self and family and community and the Nation.

Nube: Please talk about one of the defining features of this documentary, your music.

Kwame: Yeah, music has always been a passion of mine. Before I got involved with the movement, that was my main passion, what I was aspiring to do on the streets before I was captured. And then during my captivity I still continued to record and release music with industry producers such as Big Wayne on Da Track and Playbwoi Tha Great, and they had both been signed to Boosie Badazz.

Just being able to channel what we’re going through as a people and what we’re experiencing through the pen, right? In the same way you can write a political piece, write an article for the paper and be a journalist that way, that’s the way I view my music – it’s street journalism.

By me being a revolutionary, people expect a certain level of consciousness to be in my music. But I make sure I’m not just giving you the street aspect, I’m also going to give the listener and the youth the other end of it, that when you’re living this life, when you’re in the street, this is what’s going to come with that.

Nube: You, like Tupac, still get some push back from the Elders regarding the content of your music. Knowing you’re a revolutionary, I was surprised to hear your use of the word “nigga.” As you’ve been opening my mind, will you please unpack this further?

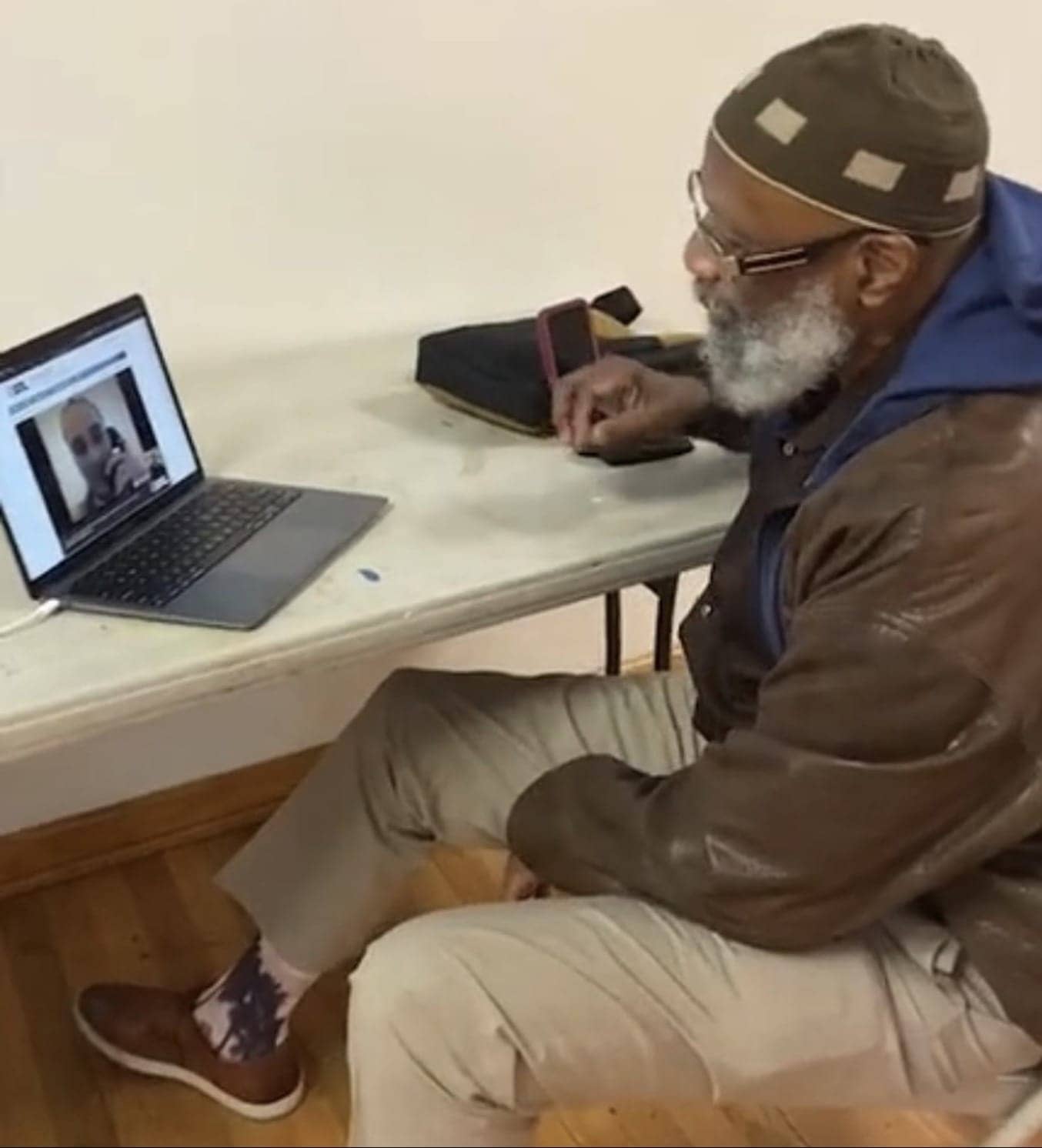

Kwame: Fo sho. When we were filming the documentary, there is a scene with me and Baba Sekou Odinga where we were on a video visit discussing the term Thug Life and the word nigga and he was telling me how when he was in the federal joint, he was one of the first people to ever see the blueprint for Thug Life. Dr. Mutulu laid it on Sekou first. And he was telling me even then he didn’t agree with it. He was telling me how his mom at the time was like, “How can you try to make something positive out of the word thug?”

I overstand, and I respect where the Elders are coming from in respect to the word nigga and us still identifying as a thug or using that context of life. I’m 32 years old; I was born in 1990. You mentioned that generational gap, where they come from a different time than us. By the time I came along, the word nigga had a whole different meaning, a whole different term of endearment, a whole different cultural aspect within our family and in the community than it did when they were coming up in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s.

What Pac has been tellin’ them for nigga, N.I.G.G.A., he said, Never Ignorant Gettin’ Goals Accomplished. And that’s not necessarily the reason or the justification for why I say nigga, but you can apply that to everything that I’m doing right now. Cuz I’m never ignorant and I’m gettin’ goals accomplished at all levels, from the music to the streets, to the property, to the movement.

Nube: Are you intentionally using the word nigga to educate the younger generation on what it means?

Kwame: Not necessarily, specifically through that acronym, but in my actions. The reason I think I’ve been successful in these camps and in the streets with reaching the younger generation that’s my age and younger is that I don’t have what my comrade calls the “pull your pants up mentality.” I’m not like, stop using that n-word, brother, and pull your pants up, brother, because as soon as you start doing that, you’ve lost them.

If that’s the approach we’re going to use with this new generation, as soon as you start talking that, they’re not trying to hear nothin’ you have to say. They’re going to be like, Bruh, I’m not trying to hear that Malcolm X, Black Power shit. But when they hear it and see it coming from me, they’re like that’s Big Bruh, that’s a thug. He comes from where I come from; I know who he was and who he is. So, if he’s talking about this New Afrikan identity and he’s tryna pass this book to me, it’s gotta be about something.

Being a street nigga, being a thug, and at the same time being a revolutionary and a New Afrikan Nationalist, is being able to tell not only the members of GDN, with Larry Hoover’s vision, but a Crip, a Blood, a Vice Lord, a Blackstone Ranger, as members of these street tribes, it’s your responsibility, it’s your obligation to go back and study your literature and study the vision of your Chief, your King or your Chairman, and then when you read that literature – and with a revolutionary mindframe – this is what we’re supposed to be doing, this is our task as community organizers, to build up our tribes and build up the People around us.

Nube: We’re constantly bombarded by the mainstream media narrative that speaks of us as nothing but criminals, as marginalized victims rather than people oppressed and brutalized by the government. Do you have something to say about the importance of independent Black media?

Kwame: Absolutely, that’s something me and Baba Bilal Sunni Ali have been talking about and trying to create for a couple years now. That’s going to be one of our main decolonization programs when we get this New Afrikan People’s Center built. We’re going to have a virtual studio built for a multi-media hub where we can control the narrative. Because as you mentioned right now one of the main tools in mass psychology is establishment media. We are not in control of our own destinies. We are not in control of the narrative that’s being put down in regards to our People.

Right now one of the main tools in mass psychology is establishment media.

And that’s why the Bay View newspaper is so important, because there’s nothing else like it in the country. It allows us to become our own journalists and our own media and put a spotlight on situations that our People are only hearing and seeing through the lens of the oppressor and the colonizer in a way that they want the masses to see and respond to these situations. But when we can flip that and establish our own institutions, we can then put that propaganda onto our People as a form of decolonization to break those psychological chains of slavery.

Nube: Lastly, would you like to say something about Black August and your event that’s coming up?

Kwame: Absolutely. You know, Black August symbolizes a month of resistance for our people and our struggle. The first two years that I was down here in the SHU, there were hunger strikes and outside demonstrations and we tied that into the National Prison Strikes on Aug. 21 through Sept. 9. So, I’ve always used this time to educate the Brothas inside and make sure that we hold study groups during that time period.

This year, we’re having a Black August event in Terre Haute. As I mentioned, we just recently purchased a building in my community that used to be a New Afrikan-owned grocery store, and now we’ll be using that as a People’s Program in Terre Haute to facilitate these decolonization programs.

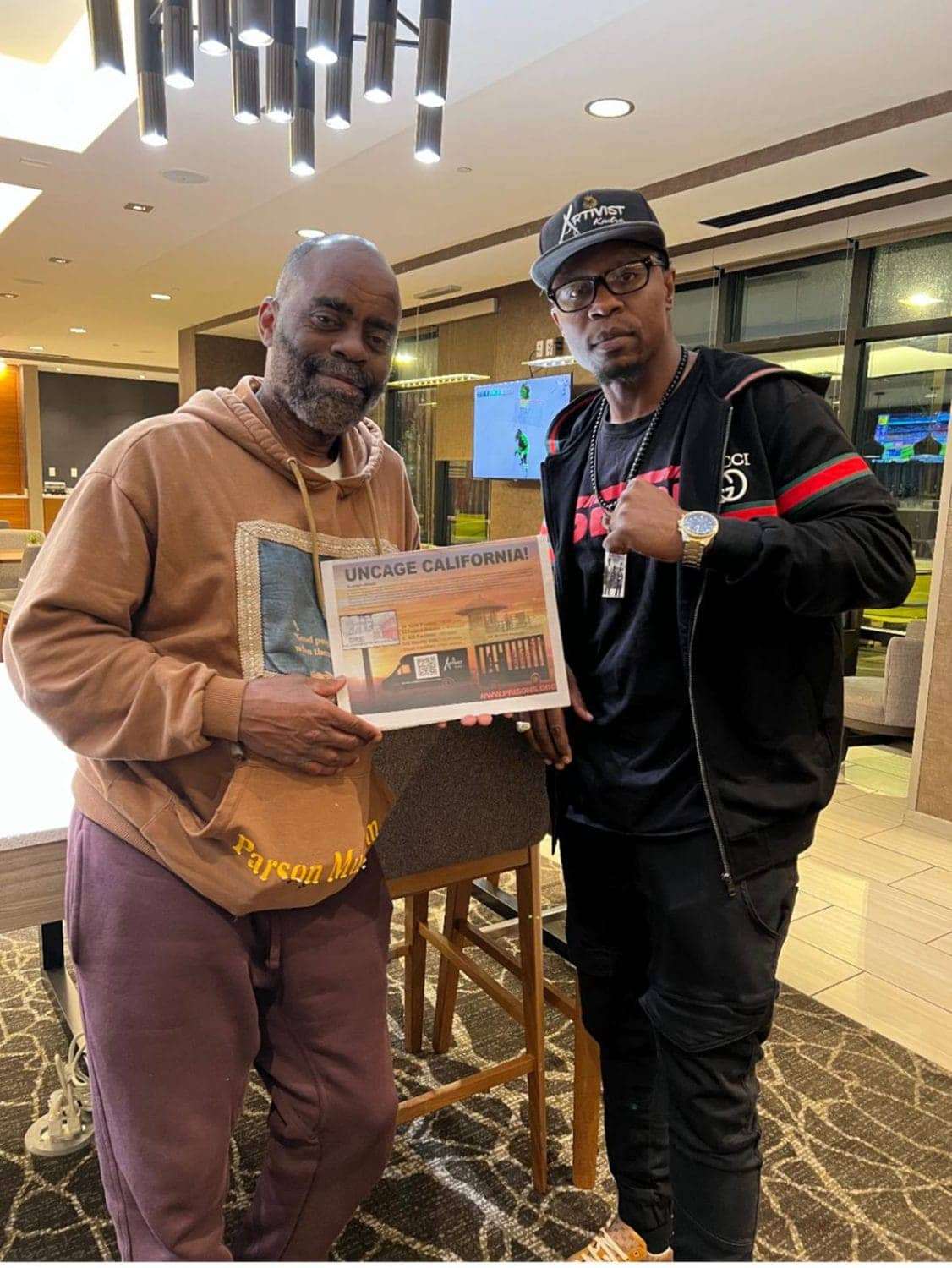

We got the Brotha Rick Ross coming here just to help put a spotlight on that and raise awareness and funding for what we’re trying to do. I also recently founded the New Afrikan Business and Landowners Coalition for Social and Economic Development, and so far we have seven New African-owned businesses and Youth Athletic Mentor programs who have already signed on and are hosting the Black August event with us.

We’ll be giving away 50 backpacks and school supplies to the kids. It’s about bringing awareness and heightening the consciousness of the community and the need for resistance when it comes to the miseducation of our land and institutions in our communities, specifically the Community Liberation Center that my grandfather established that’s been gentrified.

One of the first objectives of the New Afrikan Business and Landowners Coalition is to come together collectively into that Center. And so I’m looking forward to the outcome of all this, and hopefully this Black August event will become an annual thing in my city.

Nube: Kwame, we appreciate you. You’re such a mentor and an inspiration.

Kwame: I appreciate you for giving me this opportunity to get this out to the People.

Bay View Editor Nube Brown is a developing New Afrikan, abolitionist and Liberate the Caged Voices columnist. She hosts Prison Focus Radio on KPOO 89.5 San Francisco and KPOO.com every Thursday 11:00 to noon and also broadcasts Bay View TV Breaking News on Instagram @sfbayview every weekday morning from 9:00 to 10:00 a.m. Connect with her at nube@sfbayview.com.

Kwame Shakur is a New Afrikan political prisoner currently enslaved in solitary confinement at the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility. He is the chairman and co-founder, with Shaka Shakur, of the New Afrikan Liberation Collective and is the national director of Prison Lives Matter. To get involved with his Freedom Campaign, please email kwameshakurdefense@protonmail.com. Donate to the New Afrikan People’s Center here. Send our brother some love and light: Kwame Shakur, 149677, WVCF, P.O. Box 1111, Carlisle, IN 47838.