World premiere of Marcus Gardley’s San Francisco-set modern-verse translation of ‘King Lear’

by Cecil Brown

In his own words in 1979, James Baldwin spoke about his experiences as a Black writer with the civil rights movement. The speech took place at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I’m going to improvise like a writer on some assumptions. And though I feel a little uneasy in doing this, in saying this, nevertheless, what a writer is obliged at some point to realize is that he’s involved in a language which he has to change.”

Standing there in that audience in Wheeler Auditorium, as a witness and now a survivor, I recall what Mr. Baldwin said, which is appropriate for the theatrical production, Marcus Gardley’s new translation of “King Lear,” that I am reviewing:

“For example, for a Black writer,” Mr. Baldwin told the largely Black academics at UC Berkeley that evening, “especially in this country, to be born into the English language is to realize that the assumptions of the language, the assumptions on which the language operates, are his enemy.”

This insight drew a breath from the audience that evening. I can still remember the gasp.

They felt the same way that Baldwin did about the control used against us through the English language.

Baldwin went on in measured rhythm and pace to a better way to make his point. He said that the control that the English language presents leads to Black exploitation. He suggested that the writer had to recognize the English language as his enemy. The writer must recognize that he has to take it over – and change it.

“When Othello kills Desdemona, for example,” Baldwin said that night, “‘I threw away a pearl, richer than all my tribe.’ I was very young when I read that and I wondered about that ‘richer than my tribe!’”

“I really had to think about being as Black as sin, as Black as night, Black-heart.”

That was in 1979.

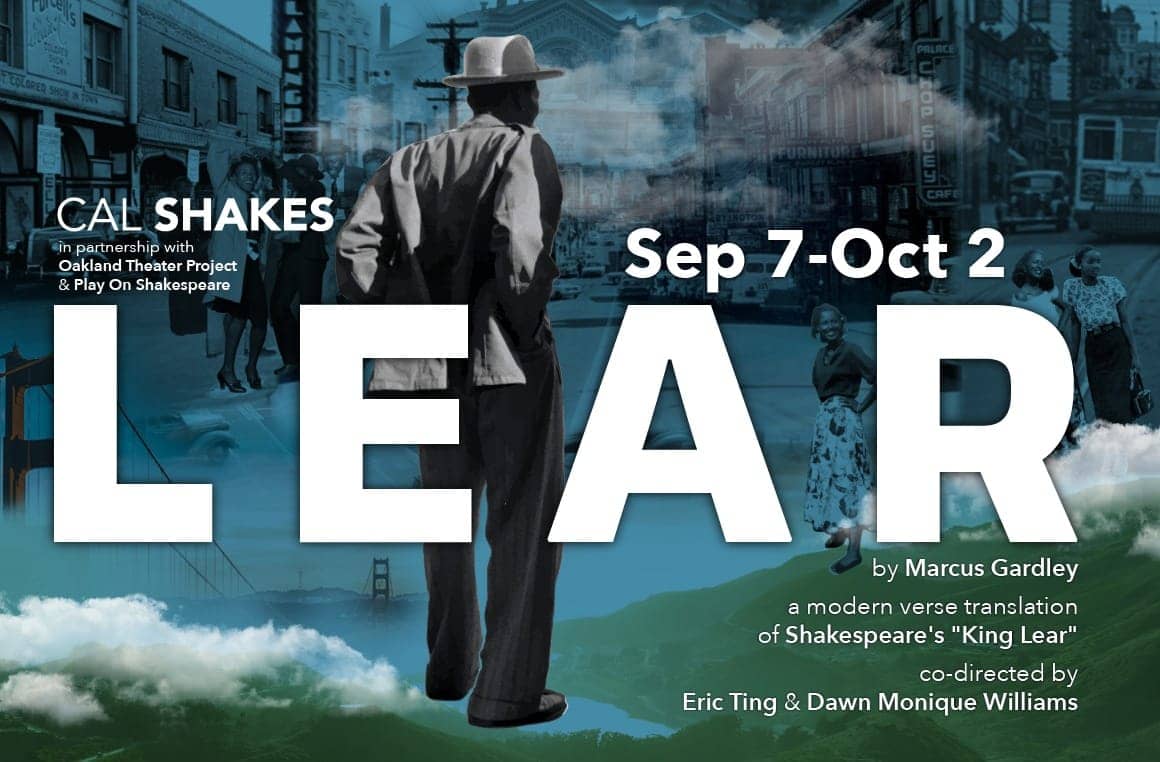

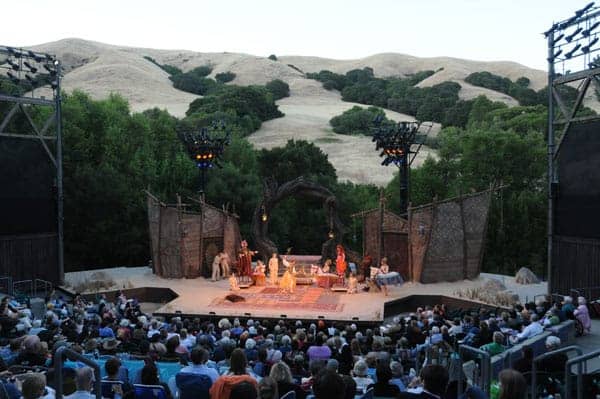

Now it is 2022. I am seated with an audience on the opening night of “Lear,” a play adapted from Shakespeare’s “King Lear” by Marcus Gardley, who was born in Oakland and now lives in Los Angeles. “Lear” runs through Oct. 2 at Cal Shakes’ Bruns Memorial Amphitheater in Orinda.

In some sense, the presentation of this brilliant work of art, “Lear,” is the fruition of a struggle to take over the English language that was suggested by Mr. Baldwin back in 1979.

On the opening night of the play, we were entertained under the Orinda skies – a moon and sky of shiny stars were the setting. Occasionally, wild dogs howled distantly.

Starring James A. Williams as “Lear,” the cast will also include Michael J. Asberry as Gloucester, Emma Van Lare as Regan, Dov Hassan as Cornwall, Sam Jackson as Cordelia and The Comic, Leontyne Mbele-Mbong as Goneril, Cathleen Riddley as Kent, Kenny Scott as Albany, Jomar Tagatac as Edmund, Dane Troy as Edgar, and Velina Brown as Black Queen.

Set in San Francisco’s Fillmore District from the eminent domain crisis through the subsequent displacement of the 1960s, “Lear” is Gardley’s deconstruction of the classic story of power, betrayal and madness. But according to Marshall McLuhan, “King Lear” is really about the modernization of power.

“The assumptions on which the language operates are his enemy!” Baldwin thundered.

Marcus Gardley would certainly agree. “Translating ‘King Lear’ was a dream, as it is my favorite Shakespearean drama,” he told the press the night of the opening.

The Bay Area is the perfect location for ‘Lear’ because of themes concerning class, the wealth gap, and the importance of family, community and legacy.

“I am elated to be able to share this timeless story with the Bay Area and to have two of my favorite directors at the helm – Eric Ting and Dawn Monique Williams. We have the honor of presenting this epic and placing it in The Bay at a pivotal time in our community’s history. The Bay Area is the perfect location for ‘Lear’ because of themes concerning class, the wealth gap, and the importance of family, community and legacy. I am certain that audiences will have an incredible time experiencing ‘Lear.’ It has been a long time since ‘black odyssey,’ and it’s great to be back home doing another classic!”

When King Lear proposes to subdivide his kingdom, he is expressing a politically daring and avant-garde intent for the early 17th century. “What he is proposing is a new way of ruling by dedicating power from the center to the margins.”

The music is jazz – the wonderful ensemble of Marcus Shelby. This is the music of working class musicians, not the music of the emerging bourgeois class. The jazz musicians represent the class of Blacks who historically escape from the oppression of middle class values – which reflect the classificational values of the white middle class. A young white female, the stage manager, as presenter, approaches the audience and tells us that we are about to begin the play, thus establishing a connection to the audience.

We are encouraged to think of this theater space as an immersive one – immersive because you are looking around yourself in the theater. In the very beginning of the show, the MC tells the audience that we want you to turn to your neighbor and say, “Hello.”

The real reason is hidden: It is to get you used to looking around a 360-degree space, which is another part of the Immersive Manifesto – the ability to make extensions of the drama into the principle of fictionalizing the world around you.

The actions that happened in the world of the “King Lear” play had a similar effect in the world of the Bay Area. For example, the cities in England are fictionalized in “Lear” to be places in the Bay Area like Hayward and Fillmore.

Now the stage manager, after encouraging the mood, turns to us and says let’s all be nice to each other and then says, “OK, let the play begin!”

Next enters a beautiful Black woman who turns to the audience in an aside. In the reality of Orinda, she is actress Velina Brown, but in the world of 1969 Fillmore, she is the “Black Queen.”

She begins to rap to the audience, to us, over the smooth rhythms of hip-hop beats. The real audience is, of course, white, but the fictionalized Blacks are mostly in their heads. The real audience were given prompts and cues that it is permissible to imagine themselves as witnesses and “survivors” of the fictionalized revolution of the ‘60s.

Historically, there has always been a conflict and resolution between Shakespeare and Black people. Coming from a very small town, Shakespeare was impressed seeing Black people on the streets of London due to the slave trade. His fascination with Black people began with his first play, “Titus Andronicus,” where he created the character Aaron the Moor, who impregnates the Queen of the Goths, and continued through the bard’s last play, “The Tempest,” where he introduces Caliban, the first recorded African American to appear on the English stage.

We have a solid history of Blacks playing Black characters in Shakespeare, beginning in the 19th century with an American Black, Ira Aldridge, playing Shakespeare’s Othello. Over the years there were great African Americans, like Roscoe Lee Brown, who played other classical roles like Oedipus at Colossus. I ran into him at the Claremont Hotel after his performance at UC Berkeley. He said that the ancient Greek plays featured large choruses like the ones that gave rise to African American culture.

Although there was great demand by an English and American public for Shakespearean roles during the ‘60s, there were only a few instances when actors began to change the language itself. No matter who the actor was, he never tampered with Shakespeare’s language.

Now you can go to YouTube and hear great versions of Shakespearean hip-hop.

This began to change when actors began to put on Shakespearean roles as a joke. One of those instances was Peter Sellers’ “Magic Christian.” There is the scene in which Sellars watches from the audience an actor “putting on” the audience of “to be or not to be” as a male strip-tease. The intercuts between the glaring eyes of women (and the men) and the off-camera cuts caused the audience – both the one in the cuts and the ones watching from the real audience – to hit the subliminal funny bone.

Then came the whole wave of the hip-hop era – when rhyming influenced every aspect of African-American performer style. So now you can go to YouTube and hear great versions of Shakespearean hip-hop. I was surprised when I saw that Stephen Greenblatt, one of the most brilliant of scholars, had also endorsed the hip-hop immersion of Shakespeare and hip-hop rhyming.

How does one go about changing the Shakespearean language to show the power of Black people who speak English too?

In the prologue to “Lear,” the playwright has one of his characters, the Black Queen, come out and express such an emotion: “Yes, we too who are Black have something to say about the world of justice and classical art!”

Change the map! and the metaphor

The first thing Mr. Gardley did in taking over the language of Shakespeare to make it his own was to change the map, literally. “The map was also a novelty in the 16th century,” wrote Marshall McLuhan in describing this scene, “and was key to the new vision of the peripheries of power and wealth.” McLuhan reminds us that Columbus was a cartographer – a map maker – before he was a navigator.

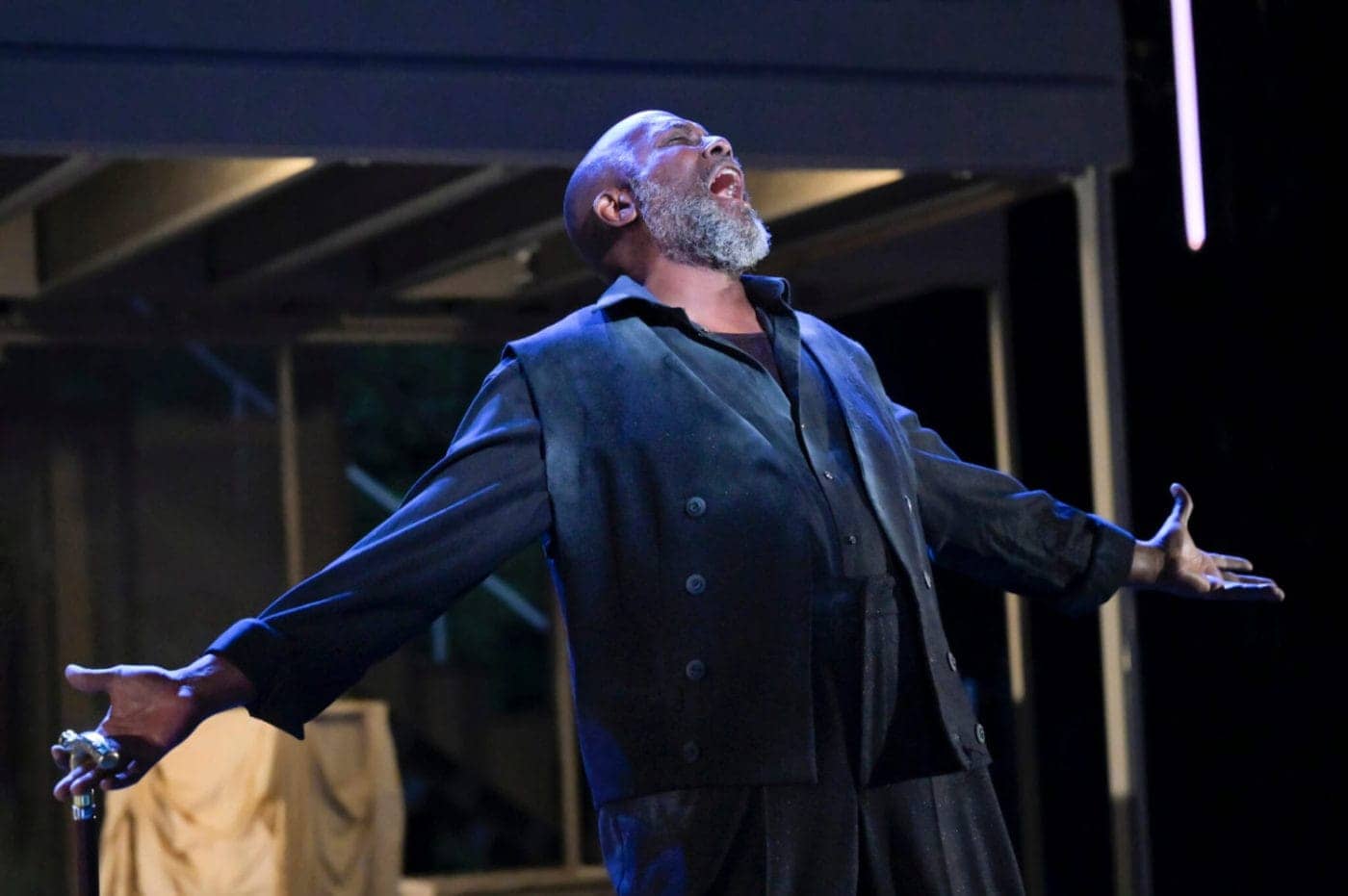

When Mr. James A. Williams enters as King Lear, you may not believe there was a real King Lear who lived in the 11th century but you are convinced that if he did live and did exist, he would probably be just like Mr. James A. Williams. Mr. Williams is a large African-American male who has a voice that you’ll imagine could come from the real King Lear if he lived.

“Get me the map!” I’m thinking his voice sounds like Moses from the mountain top.

The light on the stage shone on the map. We in the Orinda audience looked at the map under the dark sky. Lear turned to his daughters who were all lined up:

“Tell me, my daughters, / … / Which of you shall we say doth love us most? / That we our largest bounty may extend / Where nature doth with merit challenge. Goneril, / Our eldest born, speak first.”

As a master of literature and technology, Professor McLuhan rightly saw this scene as an example of the fragmentation of what had once been the medieval world of kingdom. “King Lear is a presentation of a new strategy of culture and power as it affects the state, the family, a divided psyche,” McLuhan wrote in 1962 in “The Gutenberg Galaxy.” The leader tries to do what apparently Americans in presidencies like to do – to give up a central power and transfer it to the periphery – to his daughters – and yet still be king.

“King Lear is a working model of the process of dilatation by which man translates himself from a world of roles to a world of jobs,” McLuhan observed.

After one of the most impressive speeches in the play – I call it real mythos, or myth – Mr. Williams as King Lear comes off the stage and down the aisle and walks within feet of you. It’s immersive. It was like going from a long shot on the stage to a right up in your face panning shot. One of the exciting developments of the theater is using the exit and the aisle to allow the actors to interact with the audience.

Like a navigator, Mr. Gardley made San Francisco Bay Area an object of fictional representations. “‘War and Peace’ is a novel about Napoleon,” writes Professor Kendall Walton in “Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundation of the Representational Arts.” “‘A Tale of Two Cities’ is about London, Paris, and the French Revolution.”

By this definition – we take the professor seriously and we should; art and his theory of representation is a great book on a difficult subject – the Bay Area is an object of representation for “Lear.”

Incidentally, a few years ago in his very successful “black odyssey,” Mr. Gardley used the Bay Area as an object of representation, which used the same area to fictionalize the Vietnam War to produce a different set of poetic and dramatic truths about Black culture.

Back in the 1980s, just as Black theater was waning in America, in Brazil, Augusto Boal invented a new kind of theater in which, according to Paul Heritage, he employed five full-time actors and 10 part-time actors to aid in his “street theatre style, which was based on the idea of providing interactive theatrical performances to the impoverished parts of Rio in an effort to convey political policies through the art of acting on an interpersonal level and to boost morale within poor neighborhoods through media that is very often unattainable to the general working class.

You can better understand the plot of the King Lear play by remembering something that you knew about the Black Panther Party as an example.

“Boal’s stated goal was to use theater to change the political world, not to have the political world make him change. His idea of ‘legislative theatre’ changed Brazilian political style and would later become a style of art used internationally to advocate for social organizations.[21]

“We use theatre to discuss problems of communities, workers, Blacks, women, street children, the unemployed, the homeless, etc. We don’t want a passive audience, simply watching. We propose, on the contrary, that the public participate, interfere, enter on to the stage and propose alternatives for the plot: create a new story … Theatre is political and politics is theatre.”

During the ‘80s, in Germany, there were other influences that would feed into the life of African American theater. Emerging in East Berlin during the 1980s with playwright Heine Muller, Shakespearean plays like “The Hammer Machine” have become a classic representation of Immersive Theater. In his plays, Muller encouraged audience participation by showing understanding when the audience throws eggs at his production.

As a friend of playwright Heine Mueller, I got tickets to see his latest play that was opening at the prestigious Schiller Theater. I did go and sure enough at a certain scene in the play an usher appeared with a basket of eggs. People could participate in the production by throwing eggs at the actors. Since that time, audiences were more encouraged to use the aisles of the theater.

If you are an audience member who is also a survivor of the ‘60s, then you are in a better position to understand the plot of “King Lear” in the original. As a survivor of that period, you can better understand the plot of the King Lear play by remembering something that you knew about the Black Panther Party as an example.

One of those extensions was a theme called betrayal. The Black Panther Party members were betrayed by infiltrated FBI snitches.

Just like the Panthers were infiltrated by the FBI, so in “King Lear,” his daughters and their husbands betray each other.

In the end of “Lear,” they all self-destruct, just like the members of the bougie Black people did during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. One of them poisons her own sister because she is jealous of their shared lover.

The influence of media on the characters’ behavior is a significant observation on both Shakespeare and Mr. Gardley. For both, the media is the message. For example, Shakespeare uses the fashion of note-taking and passing of notes among friends. All of Shakespeare’s “sonnets” were such notes that were passed among friends, never to be published.

In “King Lear,” most of the scenes that lead to betrayal begin with somebody discovering a note, or, as in the case of Gloucester (Michale J. Asberry) and his bastard son Edmund (Jomar Tagatac), hiding a letter. When Gloucester succeeds in getting the letter, the audience witnesses Gloucester telling them he used that as a ruse to convince his father that Edgar was trying to do him harm.

Just as in King Lear’s time, the handwritten letter could easily be divided into content and form as it is today on social media. It is a handy way users deceive each other and create false, manipulative images of themselves.

“Shakespeare seems to have missed due recognition for having in ‘King Lear’ made the first and so far as I know the only piece of verbal three dimensional perspective in any literature,” writes McLuhan in “The Gutenberg Galaxy.” Dane Troy as Edgar and Michael Asbury as Gloucester perform a brilliant scene in which Gloucester believes falsely he has been led to fall from a steep cliff.

This scene illustrates the illusion of the third dimension perspective. McLuhan says: “Gloucester is ripe for illusion because he has suddenly lost his sight. His power of visualization is now quite separate from his other senses. And it is this sense of sight in deliberate isolation from other senses that confers on man the illusion of the third dimension as Shakespeare makes explicit here.”

As we hear a lot about augmented reality and virtual reality, Shakespeare seems to have anticipated the reason we have the illusion of a third dimension.

Some representations are their own objects. Professor Walton says that “props in children’s games can be objects of the imaginings they prescribe. A doll directs players of the game not just to imagine a baby but to imagine the doll itself to be a baby. So it generates fictional truths about itself; it represents itself. Let’s call it a reflexive representation.”

In Mr. Gardley’s “Lear,” there are many significant “reflexive representations.”

In our own day, I remember sitting in his Berkeley apartment as Richard Pryor and I listened to the radio discussion between Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver disagreeing with each other because they had to talk in code.

That conversation we listen to between Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver signals the distress that Black men had due to them not having any way to prevent the white man from manipulating them. As revolutionaries, we had not developed a language that was trustworthy; we didn’t own the technology that we had to use to break down the technology that was using us.

The Fool in “King Lear” was based on the history of the Fool starting with Will Kemp; but in “Lear,” Sam Jackson, who plays Cordelia, also plays the Fool as a standup comic. The difference between these two roles is brilliantly performed and connects the historical past to the living present. “The Mutual Belief Principle” that was introduced by Professor Walton configures the connection between the Will Kemp fool in Shakespeare and Richard Pryor in the Bay Area.

“Fictional truths breed like rabbits.”

I remember the night at Mandrake when Richard said, “What’s wrong with Black Power?” The music of blues and jazz changes the form of the play, and this newly minted, fresh-flowing vernacular explodes upon being exposed.

In the character of Black Queen, Mr. Gardley uses the narrator as a storyteller. The Black Queen stands in front of the audience in Orinda and addresses them in the fictionalization of an audience from 1969. The Orinda audience is obviously quite Academy Awards-oriented yet they are fictionalized to be a Black audience that may or may not have been survivors and witnesses.

My question is now that we know how to create a Black audience for a white audience, can we do the reverse? Will Mr. Gardley and ensemble create an African-American audience as well? What is the public domain of the 1960s but a fictionalization of the principle of expelling Blacks from San Francisco?

In a recent poll it was revealed that of all the cities in America, San Francisco is the best place for dogs.

And another poll showed that the worst place in the Bay Area for a Black man is San Francisco. In 1968 there were signs at restaurants that said, “No Negroes, no Mexicans and no dogs.”

And in September 2022, the same slogan over the same neighborhood says, “Mexicans OK, dogs are fine, no Negroes.”

“Fictional truths breed like rabbits,” writes Professor Kendall Walton. “The progeny of even a few primary ones can furnish a small world rather handsomely.

“A storyteller, in a culture in which it is universally and firmly agreed that the earth is flat and that to venture too far out to sea is to risk falling off, invents a yarn about bold mariners who do sail far out to sea. No mention is made in the story of the shape of the earth or the danger. That would be unnecessary, the teller thinks, for he and his audience assume the earth in the story to be shaped as they believe it is in reality. All take it to be implied that fictionally there is, somewhere in the vast ocean, a precipice to nothingness.”

In this drama, “Lear,” storytellers give us a culture in which it is universally affirmed that San Francisco is the worst city in the Bay Area or America for Black men and women – and yet it is the best city for anybody who has a dog! The invented audience is amused.

Can the production, “Lear,” really do in reality what it has done fictionally?

In reality it has assembled a brilliant cast and ensemble of Black artists, and they have produced a great work of art – for a white audience only.

Can they actually do that for a real Black audience? Can it finally add that so that the layering of appreciation and evaluation of Blacks by themselves will be a reality and not only a fictional one?

Novelist and educator Cecil Brown, UC Berkeley professor and director of the George Moses Horton Project at the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) at Stanford University, is also known as the close friend, screenwriter and biographer of Richard Pryor and as the author of “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger,” “Stagolee Shot Billy” and most recently “Pryor Lives: How Richard Pryor Became Richard Pryor: Kiss My Rich Happy Black Ass.” Brown can be reached at browncecil8@gmail.com.