by Timothy Farrell

Introduction

One of the FROLINAN (Front for the Liberation of the New Afrikan Nation) Programs for Decolonization includes the National Alliance of New Afrikan Students (NANAS). When an individual is a cadre member of FROLINAN, they are obligated to implement the FROLINAN National Strategy and its Programs for Decolonization into their daily work within the overall movement and community in an effort to build a better society. This is the case with Prison Lives Matter and The Kwame Shakur Freedom Campaign. Each has its own Lawful Committee made up of attorneys, lawful counsel and students from around the kountry. For several years, Kwame has been networking to establish NANAS, as FROLINAN cadre believe these students are the future and will play a fundamental role in rebuilding the movement. Attorney Alec Karakatsanis, who serves on both Lawful Committees, has played a major role in forging these relationships.

Justice Initiative

Kwame’s Freedom Campaign ended 2022, by beginning what will become a long list of speaking engagements on college campuses around the kountry, starting with a group of Harvard University and Howard University pre-law students and professors on Nov. 5, as a part of Harvard’s Justice Initiative Saturday Session.

The Justice Initiative is a community of social justice-oriented law students, lawyers, faculty and activists devoted to dismantling and remaking justice systems through study, engagement, organizing and collaboration among its participants.

The session was led by Professor John Hanson, with Kwame’s participation facilitated by Karakatsanis. “Kwame is one of the most important movement organizers in the U.S. right now. He is just an incredible person who I am honored to have gotten to know in the last year or so,” Karakatsanis remarked. “He is showing how to build an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist movement, which will include getting and building a new generation of left-leaning students and lawyers who are in service of prison organizing. From Virginia to California to Indiana, there is a dearth of lawyers available to help them. We are trying to build a cadre of lawyers for the work on the inside.”

Laying the Foundation

Because he so strongly believes it is imperative to talk about decolonization and international human rights before beginning any discussion with or about law and student advocacy, Kwame began his talk to the law students and professors with a history lesson. “To get a better overstanding of what is going on with the prison movement and the outside nationalist movement, and to make it clear to be effective in our organizing, I have to give a dialectical and historical context of the relationship between the prison movement and the prison system as it relates to domestic neocolonialism in this country,” he pointed out.

In 1968, following Malcolm X’s vision, more than 500 Black nationalists met in Detroit for a Black government convention to establish its own governing body. That is where the Provisional Government of New Afrika was founded, which included the development of the New Afrikan Declaration of Independence, New Afrikan creed, New Afrikan constitution and a governing body. “All those things are needed in order to be acknowledged and respected by the international community in our fight for liberation. From then until now, our most prolific leaders and leading theorists have been held captive in these prison systems. Once they are in these prison systems, they have been held in solitary confinement for years and decades on end in an attempt to silence and censor those aspirations,” Kwame stated.

He noted that the prison movement started in the late 1960s and early 1970s around the formation of the Republic of New Afrika, the Black Panther Party and other organizations. “Huey P. Newton used to say you can’t talk about fighting racism without trying to destroy capitalism and vice-versa. What I say in this new generation of prison activists and outside organizers is that we can’t talk about prison abolition or prison reform without also being in support of the decolonization of captive and oppressed nations here within the U.S.,” he expressed.

Political prisoners and prisoners of war like Mumia Abu-Jamal, Ruchell Magee, H. Rap Brown (now known as Jamil Al-Amin) were targeted and locked up during the course of their fight for freedom and to liberate the captive Afrikan nation here in North America.

“Coming into the movement, it is important to understand what we are rebuilding and where this started from. There are many captive nations within the U.S. who are being oppressed, that have been stripped of their national identity to be turned into inferior race and class groups. The race groups of white and Black are fabricated social constructs of capitalism. When Malcolm X was assassinated, he was fighting for the liberation of the Black nation, for us to be able to go to the United Nations and tell the international community that under international law we have the inherent right to struggle against colonial powers to self-govern ourselves and to be a national, independent, autonomous movement body of people.

“The formation of these radical organizations and their beliefs are why a lot of people around the world who we recognize as political prisoners and prisoners of war like Mumia Abu-Jamal, Ruchell Magee, H. Rap Brown (now known as Jamil Al-Amin) were targeted and locked up during the course of their fight for freedom and to liberate the captive Afrikan nation here in North America. J. Edgar Hoover (FBI Director), was targeting these individuals through COINTELPRO (short for Counterintelligence Program) to suppress their voices and aspirations to be a truly free and independent nation with the right of self-determination,” Kwame explained.

Connecting New Afrikan Liberation Collective and Prison Lives Matter

In 2015, when Kwame became a citizen of the Republic of New Afrika and proclaimed his nationality, he went back and studied the prison movement and the outside revolutionary movement, and noticed that for the past 30+ years, there was this segmentation and sectarianism within the outside movement that you have all of these people all over the nation fighting for the same thing, but nobody was connected. “I was talking to people in New York, Detroit, Texas, and California who were doing the same work, but weren’t in tune with one another. That led to my co-founder Shaka Shakur and I starting the New Afrikan Liberation Collective (NALC) and we started establishing our infrastructure within the New Afrikan nation of all the top leaders and political prisoners that would help us create it and a national database that would make us stronger and implementing educational units around the country to develop cadre,” he informed.

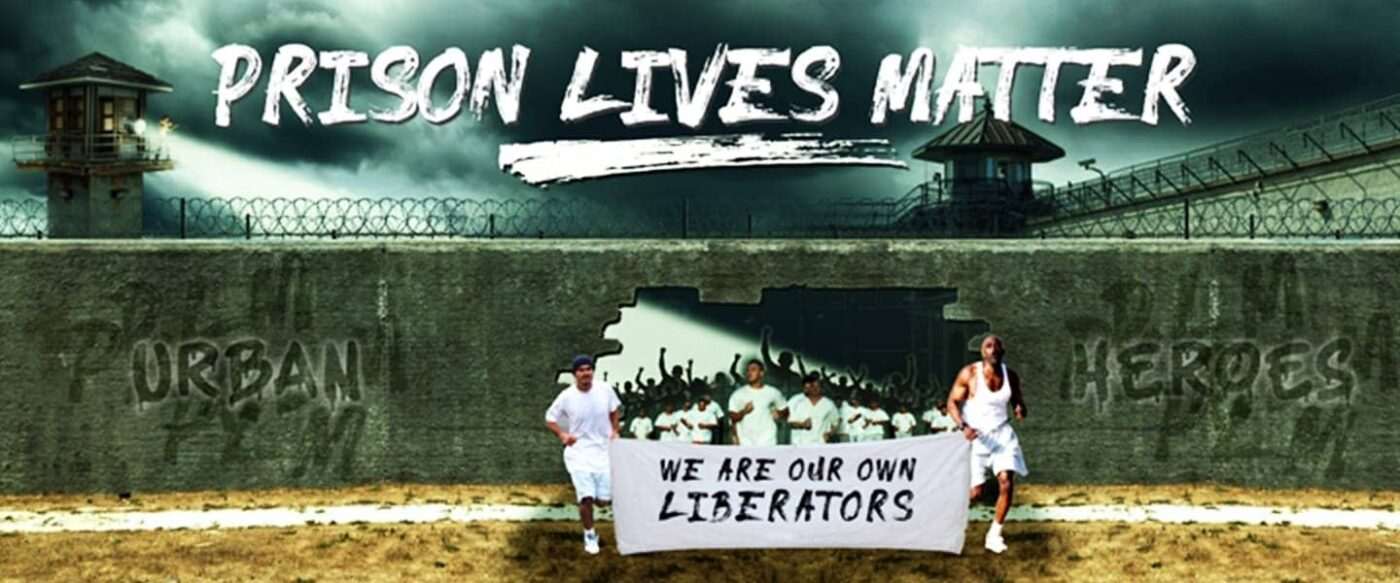

“In the course of this work, individuals from Virginia had reached out to me and asked that I start something called Prison Lives Matter, so I asked what that would entail,” he continued. “At this time, the Black Lives Matter movement was popping pretty heavily all around the country, so I asked if it was an offshoot of that. They said that it wasn’t and that instead of that, they wanted me to build an educational and political platform and infrastructure for PLM. As I started to write out the mission statement, I just paused and realized that this would be just like all the countless prison formations around the country that had been taking place since the late 1960s and early 1970s.”

“What I have been doing with PLM since 2016 is to build a sustainable national infrastructure so we can not only liberate these elders, but to abolish legalized prison slavery in a realistic manner.”

Kwame took the same concept they were using with NALC to develop a united front for the New Afrikan nation and applied that to the prison movement. He started establishing the Prison Lives Matter National Coordinating Committee (NCC), reaching inside and out all around the country to the nation’s leading political prisoners and some of the top prison support groups and organizations on the street that had been active with a lot of these people being original members of the BPP and the Black Liberation Army, and the founders of the Republic of New Afrika.

“What I have been doing with PLM since 2016 is to build a sustainable national infrastructure so we can not only liberate these elders, but to abolish legalized prison slavery in a realistic manner. This can be done by establishing decolonization programs within the community so that those of you on the outside who are allies and supporters, or active members of this movement or of the oppressed nations, have the proper education and tools to fight for our freedom and to fight for prison abolition,” he told the law students and professors. “In the last two years, we have broken that NCC down into the PLM Regional Organizing Committees (ROCs) so that we are able to organize more effectively. What I had noticed for years when we were organizing within the prison movement, it was only financially and logistically realistic for us to have these events, rallies and conventions once a year where everybody could meet up. However, I was thinking if we could turn it into ROCs that people would be able to meet up and organize tangibly more effectively when it is time to respond to the call of action or even in terms of doing local, on the ground work.”

Legal Aspect

For the better part of the past year, Kwame and the NCC have been trying to establish the legal subcommittee of PLM. “I believe the key way to achieve this goal is to go on to these college campuses and be able to recruit radical, progressive-thinking attorneys, professors and pre-law students to get them involved. It has been historically easy for America and its system to silence people inside the prison, to silence poor, marginalized individuals who have been fighting for their international human rights,” he commented. “When we get people like doctors and lawyers and professors involved and you are channeling and carrying on our rally cry against genocide, it is going to be a lot harder for them to suppress that and we can actually achieve something sustainable.

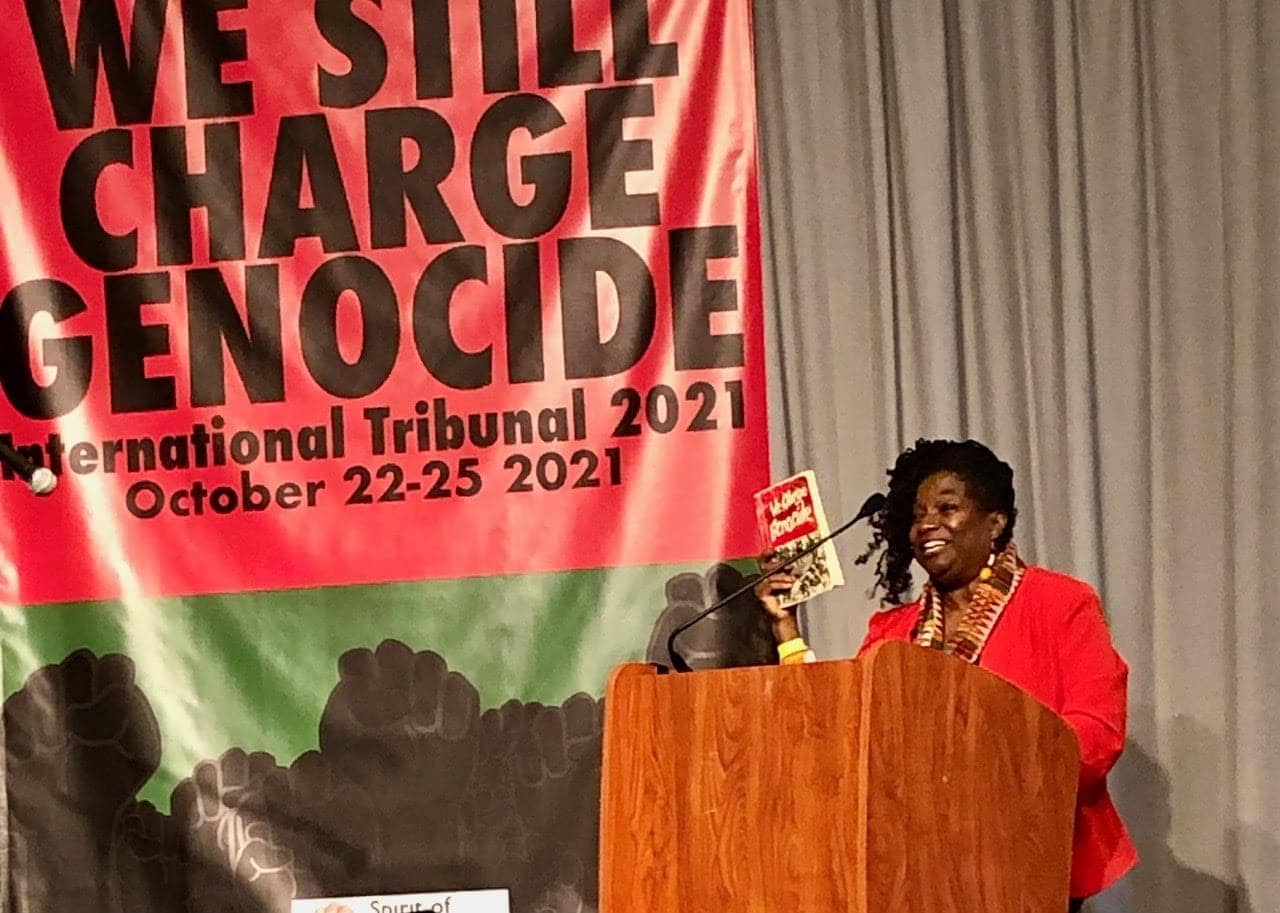

“We want these students, professors and lawyers to help us reach the international community following the Spirit of Mandela International Tribunal in New York in October 2021. We had international jurists come from around the world and hear a 50+-year chronological case against the U.S. government and its prison system and our case against genocide. In a historic, monumental conclusion, these international jurists found the U.S. guilty of genocide on all five counts brought forward.”

Although the Spirit of Mandela Tribunal was a historic event, it was unsurprisingly not covered by the mainstream media, which serves as an arm of the U.S. propaganda machine.

Karakatsanis introduced Kwame to a lawyer he used to work with named Dami Animashaun as well as other lawyers located in Washington, D.C. “Within the prison movement, what the administration knows is that this generation lacks lawyers and law clinics coming to our aid the way they did in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Another problem is that lack of movement and infrastructure on the streets and in the prisons led to those on the inside not knowing how to defend ourselves legally. The average person doesn’t even know how to file a grievance or a 1983 form or file the correct paperwork to challenge these oppressive conditions that we are subjected to,” Kwame mentioned.

“With Alex, Dami, and these other lawyers, we brought them inside the PLM legal committees behind the wall and they are helping to litigate these cases and get them into court properly, so that we can effectively overthrow these conditions we are suffering under, most of us being in solitary confinement,” he continued. “The goal of those lawyers is to do exactly what we are doing today, to get in tune with professors and law students to get you involved. We need more people like these lawyers to have the courage to get involved. That’s what we hear from these lawyers, that they are isolated and feel alone because people in their field don’t have the courage to step up and take these issues head on.”

People’s Programs for Decolonization

In Kwame’s hometown of Terre Haute, Indiana, NALC recently purchased a building that used to be a Black-owned grocery store with the help of one the PLM attorneys. The building is being turned into a decolonization center and a national training and program hub for law students, comrades and family members to build and train, to learn the proper educational tools that it will take to sustain this movement and infrastructure. The building is currently in the renovation stage.

“It is both inspiring and motivating because when I went back to study and analyze where the last movement failed and why the movement hasn’t really taken off in the past 25 years is because there was no tangible, concrete infrastructure. We’ve been writing books and giving speeches and lectures for 50 years. We’ve been organizing rallies and demonstrations for 50 years, but nobody has been able to create a movement that teaches people how to turn that theory into applicable forms of action and practice, which is what it is going to take,” Kwame elucidated.

“Getting this center together and working with law students around the country to build political education classes on these campuses and in these different regions and states will hopefully lead to other places being able to develop these buildings as well,” he said to the students. “Right now, it is really important that we have the support of all of you on this call, but it is more important that through organizing or mobilizing that we educate people and create these law clinics that we are going to have in the center as well, so that we can get local students to come and engage in these programs.”

Kwame believes the connection between prison abolition and decolonization cannot be overstated. “A lot of people have this romanticized fantasy of a bulldozer coming and knocking down prisons and them just letting us all out because we organize a protest or a demonstration, much like their romanticized fantasy of North American revolutionaries who study movements of the past in third world nations where these movements overthrew capitalism in a single uprising,” he described.

Get the documents from the (Spirit of Mandela) International Tribunal and understand the international law that we are supposed to be protected under.

“What we are trying to do now is more realistic and tangible in that the way we abolish slavery or the way that we abolish capitalism is not to overthrow, but to build these centers and to have these hubs and these programs that directly eradicate capitalism and genocide and oppression in our communities when we are having ‘feed the people’ programs or having political education programs or after-school programs, and affordable childcare programs that will be employing out of these facilities. That’s the way we abolish prison slavery, by eradicating that pipeline from the community to the prisons and from the schools to the prisons.

“When we can get these kids started out at three and four years old and we are able to not only provide affordable health care and childcare, we will be educating them in the same way, so this next generation doesn’t have to go through what I had to go through, and my forerunners before me went through, having to wait until we were in prison or be 25 or 30 years old to get conscious and socially aware to know what needs to change.”

Next Steps

After Kwame’s presentation to the Justice Initiative listeners, there was time for just one question, which was an important one. A student asked, “What is the number one thing law students can be doing right now to help with your movement or assist in any way?”

“One of the main things you can do now is to get the documents from the (Spirit of Mandela) International Tribunal and understand the international law that we are supposed to be protected under,” Kwame responded. “You will see how the U.S. is violating international law within its borders to suppress our aspirations for educational, social, economic and cultural development.

“Another important step is reading and studying, reaching out to other like-minded students on your campus and working with us to start a political education group, even if it’s once a month, just to understand the dialectical and historical relationship and connection to the prison movement and oppressed nations within the confines of the U.S. border. Anything short of that, we are just going to be talking about prison reform and we are not going to be able to initiate any real justice.”

Veteran Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army member Jalil Muntaqim, author of “We Are Our Own Liberators,” the blueprint Kwame uses for his revolutionary work, recently spoke about the importance of college students becoming engaged in the struggle. “We are raising a legacy of resistance against capitalist imperialism and white supremacy in terms of understanding our struggle. In the course of that work, we are building toward national independence for Black, Brown and Indigenous people. In order to accomplish this, it is extremely necessary to reach college students, building the foundation for which we are enduring our struggle will have continuity from one generation to the next, historically and contemporarily,” he shared.

Muntaqim acknowledged that there is work to be done on the students’ part to not be part of the petty bourgeoisie that assimilates into the system. “We need to have our college students understand the language of the streets and those on the streets to be at a higher intellectual level that college students are bringing. We must unite our people ideologically on the foundation of the three-phase theory of national independence. Students need to raise the issues of white supremacy and assimilation, and be supportive of decolonization programs in the community,” he remarked. “They have intellectual and material capacity in some cases. HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) and other colleges engaged in the struggle are ensuring our future, passing the baton from one generation to the next.

“The most important thing now is building infrastructure and being able to get this People’s Program for Decolonization center off the ground so that we are able to get local, pre-law students and other college students from this city and state involved,” he concluded. “We also want lawyers like Alec and Dami to be able to come to the building and help develop the law clinic so that we are able to understand not only our civil rights, but also our international human rights so that we can properly defend ourselves on all levels. At the same time, building these educational units on campuses with whoever is interested can contact us and let us know how we can plug them into a city or statewide committee in their area.”

To find out more information about the New Afrikan Liberation Collective and to donate to the building renovation costs, go to https://www.newafrikanliberation.org/ and click “Land Fund” under “Donate.” For more information on Prison Lives Matter, go to https://www.supportprisonlives.org/.

Kwame Beans Shakur is the National Director of Prison Lives Matter and Co-Founder and Chairman of the New Afrikan Liberation Collective. He is currently enslaved by the Indiana Department of Corrections.

Located in Cleveland, Ohio, Timothy Farrell is a journalist and a member of the Prison Lives Matter National Coordinating Committee. He is also part of the Kwame Shakur Freedom Campaign, the Free Kamau Sadiki Campaign, and the Mumia Abu-Jamal Love Not Phear Movement. He can be reached at tpfarrell22@gmail.com.