Soledad State Prison’s anti-Black racism and why we should choose abolition over prison reform

by Talib Williams

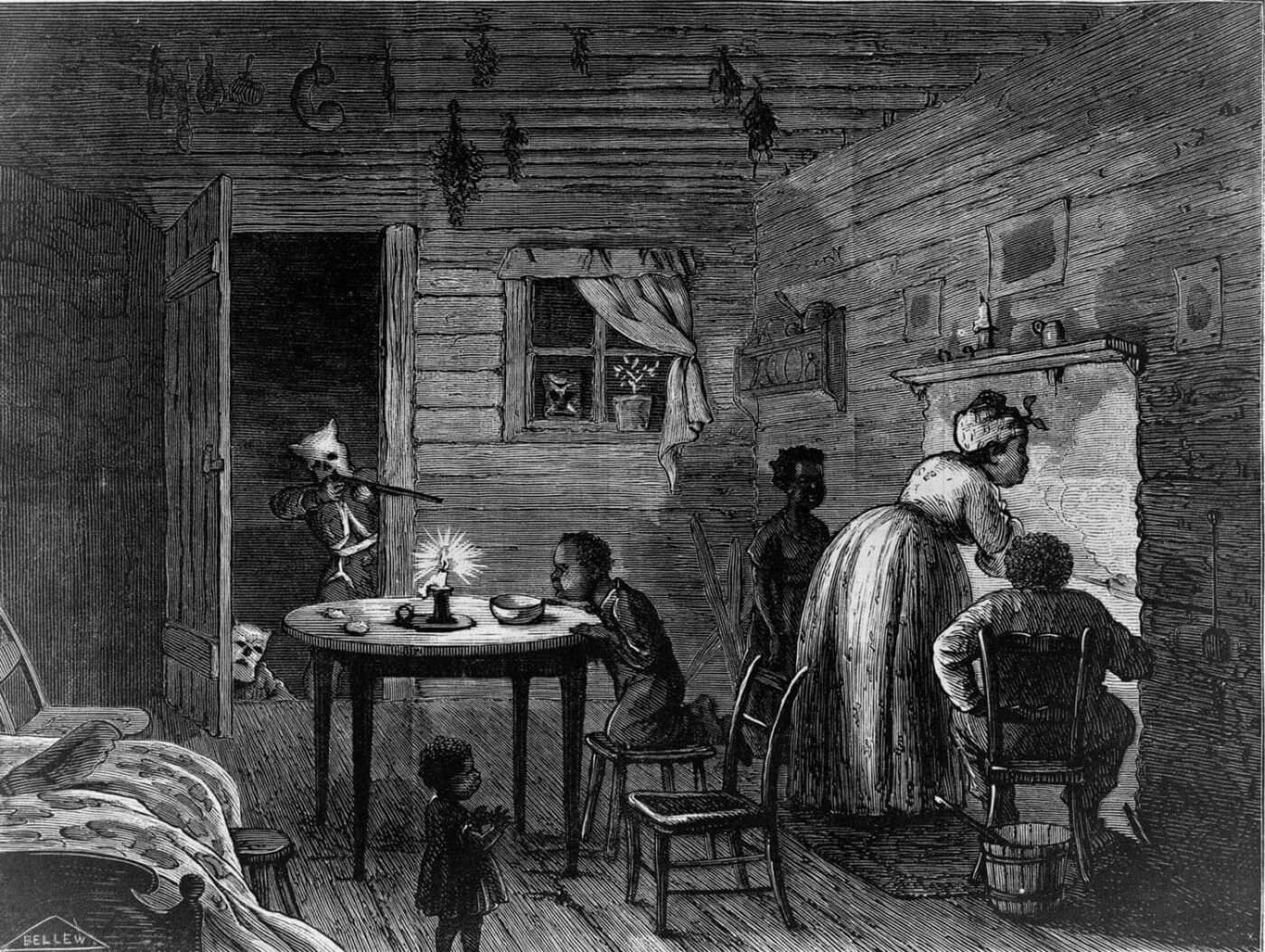

From the southern horrors of falsely accused Black people being stolen from prisons throughout the south and lynched, to the same reality of falsely accused incarcerated Black people being stolen from prison cells in the early morning hours at Soledad – there is no difference between racist correctional officers of today and the belligerent ideology of racists of yester-year.

The long history of racialized violence committed against Black people by police forces and white vigilantes are not aberrations; they are the very reflection of the reality that is America: concerted – often legalized – violence with the purpose of instilling fear, intimidating Black life to the point of self-censorship.

Whether it is the brutality of the slaver’s whip, the bombing and burning of Black Wall Street or the bombing and burning of Black churches in Birmingham, or the southern horrors of Black bodies lynched in the southern delta by what one newspaper reported as “a squad of 20 men,” or Black people at Soledad prison in California being violently raided by a group of correctional officers colloquially known as “The Squad.” The purpose is one and the same.

It wasn’t until Ida B. Wells fearlessly investigated and reported on the reality behind the lynching of Black men in America, published in her groundbreaking statistical report “The Red Record,” that the truth was exposed. Patrisse Cullors writes in her timely released “An Abolitionist’s Handbook” that, before the investigative reporting of Wells:

“The official reports of the lynchings of Black men, much like the murders of Black people by police today, were largely accepted – the stories propagated the ideas that Black men were rapists threatening the safety and virginity of white women and that white vigilantes were just meting out justice to these Black criminals.” The reality however, is that these accusations were a smokescreen.

Wells’ journalism exposed that these lynchings were used as economic and political retaliation fueled by white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Not dissimilar to white violence of today, said to be fueled by “Replacement Theory,” white men have historically viewed the upward mobility and independence of others as a threat – even the independence of the white women they claimed to defend.

Ibram X. Kendi clarifies this in his “Stamped From the Beginning,” where he explains that, in the fearful minds of fragile white men, that it didn’t matter where the so-called “threat” came from. “After 1830, young, single and white working-class women earning wages outside the home were growing less dependent on men financially and becoming more sexually free. White male gang rapes of white women began to appear around the same time as the gang assaults by white men on Black people,” writes Kendi. “Both were desperate attempts to maintain white male supremacy.”

Racialized white violence, although indiscriminate, has ever tried to justify itself by pointing towards a non-existent Black criminality. It didn’t matter that white men were almost exclusively responsible for the sexual assault of white women. What mattered, and what was exploited, was what people believed, and what these white men could convince people to believe.

Everything that we are experiencing here at Soledad today is rooted in this reality. The failure to understand this reality in connection to America’s prison system is a failure to understand white supremacy. However, to truly understand this we must look to the past.

Jordan v. Fitzharris was the first successful civil rights complaint ever filed against a state prison. In 1964, this case exposed what it meant to be an incarcerated person at Soledad in the ‘60s. Robert Jordan, an incarcerated Black man who was placed in solitary confinement for “disciplinary infractions,” had to be “smuggled a pencil and paper to write a letter about the conditions within Soledad,” wrote the late Newsweek journalist Min S. Yee, in his “The Melancholy History of Soledad Prison.”

“When he tried to file a petition in court against these conditions, a guard tore the petition up.” It was only after numerous attempts to alert the court that his petition made it in front of U.S. District Court Chief Judge George B. Harris. This case would expose what Judge Harris described as “conditions of a shocking and debased nature.”

Countless incarcerated people described, under oath, instances of being disciplined by being thrown completely naked into “strip cells,” attacked by guards and called racial slurs. “By the time Jordan himself appeared as the last inmate witness, descriptions of the strip cell conditions in Soledad’s O-wing were becoming redundant,” writes Yee.

“Jordan testified that he was placed in the cell naked, that it was completely dark, that his cell reeked from the urine and feces of former occupants, that he vomited twice and cleaned that up with his own hands, that he was not allowed to wash or shower, that some days his toilet – the circular hole in the cement floor – was not flushed.”

You would think that the prison would deny these allegations. But Soledad Warden Cletus Fitzharris, whom the complaint was filed against, actually defended these conditions. This wasn’t an isolated event. This was the norm.

Fitzharris made this clear in open court when he said: “Nobody’s happy with having to treat human beings like this, but some human beings can’t be treated otherwise, that we know of.” It was this blatant disregard for human decency that caused the judge to rule in favor of Jordan.

This case was groundbreaking in that it was the first to expose the reality of what it meant to be incarcerated at a prison that was touted publically as a “modern utopia.” However, in spite of exposing such horrific conditions the Judge’s ruling had little effect on the ground.

In fact, the Judge himself in reflecting on this case years later said: “The problems at Soledad transcended our limited investigation.” He told the late journalist Min S. Yee that “there were many questions about prison conditions and prison procedures,” which he wanted to look into, but the court “had neither the money nor the power to pursue those matters.”

Although Jordan v. Fitzharris didn’t greatly affect prison conditions, its success proved to incarcerated people, especially Black people, that civil rights litigation could be successful. The medium available for incarcerated people to assert their federal civil rights is Section 1983 – originally known as Section 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 – which, although available to everyone, was passed specifically to help Black people enforce newly enacted constitutional rights post-slavery, and the incarcerated Black people at Soledad knew this. They saw a direct connection between their condition as incarcerated Black people and the not-so-distant past of chattel slavery.

“Nobody’s happy with having to treat human beings like this, but some human beings can’t be treated otherwise, that we know of.”

However, while this may have emboldened incarcerated Black people, it infuriated prison administrators. To change the narrative, prison officials devised a plan to convince the public that there was a problem at the prison. Enter the rise in racialized violence against incarcerated Black people instigated by correctional officers.

The ‘60s saw the emergence of a Black liberation movement that inspired a pride and sense of independence that hadn’t been witnessed since the uprisings of enslaved Africans in the antebellum south. Black people in America refused to be silent about systemic oppression. This infuriated white supremacists and all who benefited from the economic and political subjugation of Black people.

Prisons cannot be separated from this American tragedy. In fact, the prison system is central to having a complete understanding of how this country carefully crafted its anti-Black narrative that has affected (and infected) every segment of this society. Black male violence, as it has always been, was used by prison administrators to justify anti-Black racism disguised as law and order.

As Ibram X. Kendi wrote in his “Stamped From The Beginning,” “racist ideas always seemed to arrive right on time to dress up the ugly economic and political exploitation of African people.” In other words, throughout the history of this country, whenever the dominant culture sought to achieve its economic or political ends, it resorted to racial animosities to mask its true intent.

Black people would be targeted in a number of ways. Prison officials aligned themselves with the sentiment of the nation. Soledad was already staffed “with bigoted guards who found it easy to practice both the subtler and the crasser forms of white racism, pitting white against Black to foment racial hostilities,” writes Yee. Black people would be left on the tier with racist white or hispanic incarcerated people – with three-to-one or six-to-one ratios – who would attack them while guards watched.

Prison administrators would like to point to this period of Soledad’s history as purely violent and brutal. But what they won’t tell you is that they wanted it this way, that its officers were complicit in creating the conditions for such violence to exist. They were trying to get Black people to react violently – to prove to the wider public that these criminals were uncontrollably violent animals.

“By the summer of 1969, mutual fears and racial animosities between Blacks and whites had increased to such intensity that five Black prisoners tried to take their complaints and fears to court,” writes Yee. “Led by W.L. Nolen, a prison boxing champion who was quickly becoming politicized, the group filed civil suits against warden Fitzharris, the Department of Corrections and several guards.” Nolen’s suits charged that the guards were fomenting racial strife by helping their white inmate “confederates” attack incarcerated Black people by purposely leaving Black people on the tier outnumbered.

This case never made it to trial. On Jan.13, 1970 “four months after he wrote the petition Nolen was shot to death by an O-wing guard,” writes Yee. “Two other Black inmates, one of whom signed Nolen’s petition, were also shot to death.”

For years prison administrators tried to deny that there was a problem at Soledad. However, when these three Black men were murdered in solitary confinement by an officer in the gun tower, the state was forced to acknowledge Soledad’s brutal racism. Had prison administrators sanctioned the assassination of Black men who were exercising their constitutional rights? When it was discovered that two of the three killed were involved in pending lawsuits against the prison, journalists would ask this very question.

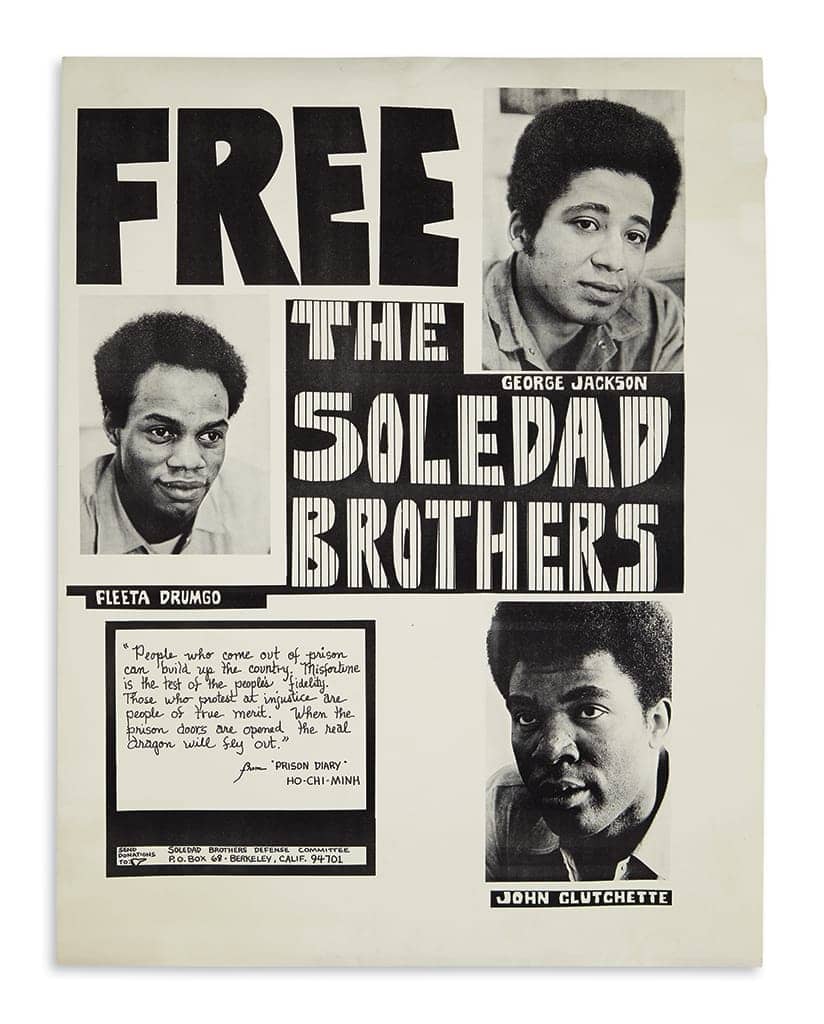

Things would intensify after the murder of an officer in the prison’s Y-wing – suspected as retaliation for the murders in O-wing. Three Black men, whom the prison had previously labeled “Black Radicals,” were charged with the murder (John Cluchette, Fleeta Drumgo and George Jackson – collectively known as “The Soledad Brothers”). They were immediately placed in O-wing.

What followed was a Senate investigation into the conditions at Soledad prison. “What prompted the investigation,” writes Yee, “was the number of telephone calls and letters that state senators and assemblymen were receiving in their district offices and Sacramento.” The last thing prison officials wanted was a group of liberal “nigger-loving” outsiders – to be prying into the conditions of the prison. However, the senate would eventually prevail being granted limited access to the prison.

The thing about racist institutions is that, no matter how hard they try to mask their hatred for Black people, it always inevitably reveals itself. One legislative aide who accompanied the senators and assembly members on their tours of Soledad, mentioned – to then-Warden Fitzharris – that an O-wing officer named Maddix had been exceedingly racist toward him. “If that happens to me,” he asked, “what do you think happens to the inmates when the doors are closed and he’s left in charge?”

The events surrounding Soledad and the Soledad Brothers inform what we are experiencing today.

The warden would deny that his officers were racist. The problem wasn’t the guards, but “uncontrollably violent” incarcerated people. It didn’t help that then-Governor Ronald Regan officially sanctioned this racism when he said at a press conference about Soledad, “what you are seeing reflected inside the institution is a reflection of what is taking place outside. The growth of prison violence merely reflects the fact that a greater percentage of men in California prisons today are hard core criminals.”

The assembly members weren’t buying it. They concluded in their official report, that “even if a small fraction of what the inmates charged was true, as the investigators and lawmakers believed, then that was enough to amount to a strong indictment of the prison’s employees (on all levels) as cruel, vindictive, dangerous men who should not be permitted to control the lives of the 2,800 men in Soledad.” It was this investigation which caused then-Assemblyman, the late Willie Brown, to declare, “Soledad is the worst hellhole in America.”

The events surrounding Soledad and the Soledad Brothers inform what we are experiencing today. Nothing has changed. The real fear of the Fitzharris administration wasn’t Black male violence, but civil litigation by Black people. (The same can be said about Soledad’s administration under Koenig.) However, if officers could goad Black people into violent confrontations then those incidents would be exploited and used as a smokescreen. It is these incidents that are used to criminalize Black people today.

This is an important point that must not be overlooked. “The white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” writes Patrisse Cullors, “is designed and held in place with trauma. From enslavement to the activity of the Klan to the movements of the police, it’s all about taunting and terrorizing, daring the people it is keeping down to react violently.”

The Soledad Brothers and George Jackson are undoubtedly the most often used names by prison officials to point towards Black criminality. Reference is made often to the Y-wing murder to point towards the potentiality of Black male violence. However, two of the three would go to trial and be acquitted, while one – George Jackson – would be killed before he could stand trial where he was likely to be acquitted as well.

The way in which prison officials have crafted its anti-Black racism, has made it that even mentioning the name George Jackson is a criminal act. This isn’t by chance. As mentioned in the beginning of this piece, racialized white violence is perpetrated with the intent of intimidating Black life to the point of self-censorship.

This was understood by Jackson, as well. “George Jackson,’” as he is remembered today, wasn’t born into existence. He was created by this system. George Jackson the person simply wanted to expose a corrupt system. One of the Branson brothers – who revealed the plot of prison officials to frame the Soledad Brothers – said that George Jackson once said to him: “Ten years now I’ve been here for a little old chicken-shit robbery at a gas station. They don’t want me out because they know that when I get out I’m going to write about this place.”

He didn’t say “when I get out I’m going to bomb this place.” When you objectively read the writing of George Jackson and what is written about him, there is a general consensus that who he became isn’t who he started out as. He wasn’t always the “violent revolutionary” that he is remembered today as. At the heart of who he was, was a writer – an award-winning one at that.

However, he would eventually embrace an ideology that the late bell hooks in her book, “We Real Cool,” called “tragically naive.” hooks explains that the very foundation of this country, being rooted in white supremacist capitalist imperialist patriarchy, is supported by our buying into the racialized stereotypes that we know all too well – chief among them being the violent reactionary. This was my main critique of George Jackson, as hooks explains: “Paradoxically, by embracing the ethos of violence, Jackson and his comrades were not defying imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy; unwittingly, they were expressing their allegiance.”

“The white supremacist capitalist patriarchy is designed and held in place with trauma.”

Therefore, when we talk about critiquing the system we mean in its entirety, holistically. We are not going to criminalize human beings as is done by the system. We are going to speak the truth in its entirety. Incarcerated people – including George Jackson – made a tragic mistake by promoting violence, but the system is equally as wrong for creating the conditions for the violence to exist, and promoting it. We can’t criticize one without the other.

George Jackson is widely known as having said that prison officials on numerous occasions tried to have him killed. One event that has been verified and sworn to in an affidavit is both revealing and troubling. Allen Mancino – an incarcerated white person who was in O-wing when the Soledad Brothers were there awaiting trial – told a lawyer that O-wing officers, accompanied by a captain Moody had abducted him from his cell in O-wing and had taken him through the “tunnel” under the prison in an effort to intimidate him into agreeing to murder George Jackson.

“Moody began to address me and asked how I liked being among the ‘niggers’ on the second tier, and asked how I felt about George Jackson specifically. He asked if I would care if anything might happen to George Jackson, to which I answered that I didn’t care one way or another. Moody then asked me directly if I would kill George Jackson. He said that he did not want another Eldridge Cleaver … Moody then hypothesized a situation where I would be taken out in the yard one night to locate a knife. He said that it would be unfortunate if I should break toward the fence and be shot if such an event actually happened.

“I understood this hypothetical to be a direct threat on my life if I did not kill George Jackson. I realized that Moody was completely serious.” Three days later – after the officers realized he wouldn’t carry out their plan – Mancino would be transferred out of Soledad to Chino State Prison.

These are the types of things the prison wants to keep from being exposed. They gladly point to the violence committed by incarcerated Black people, while remaining silent concerning their own sadistic behavior. They want the conversation to be one-sided.

They will tell you about the San Quentin massacre, but will never tell you that in response to that horrific event which caused things to unravel and devolve into one of the most violent periods in California’s prison history, the immediate response was the racist suggestion of the emergent California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA) to send incarcerated Black people back to Africa – written about in great detail by Joshua Page in his book “The Toughest Beat.”

This approach eerily resembled the response to the uprisings in the antebellum south of Denmark Vessey, Nat Turner, etc., which was to deport enslaved Africans to Panama or back to Africa. It didn’t matter that these enslaved Africans were responding to centuries of mistreatment and outright brutal punishment for simply existing. What mattered was they were perceived as a threat.

However, they were never deported. White people were in a schizophrenic conundrum. On one hand they were afraid, while on the other they were equally aware that their economic stability depended on the free labor of these enslaved Africans.

Their solution? – new laws targeting every aspect of Black life. Ibram X. Kendi, in his “Stamped From The Beginning,” writes that one jurist said: “Every distinction should be created between the whites and the negroes to make the latter feel the superiority of the former.” This dilemma was expressed in the most racist terms by Thomas Jefferson who said, “. . . we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is on one scale and self-preservation on the other.”

Our lawsuit, Williams et al. v. California Department Of Corrections And Rehabilitation et al., exposes the historical continuity of Soledad’s anti-Black racism.

This is exactly the same reality as it concerns incarcerated Black people. The principle of justice dictates that the oppression of incarcerated Black people should have been acknowledged and the necessary steps been made towards restorative justice.

However, the “self-preservation” of the prison system was the main concern of prison administrators. The deportation never took place. Instead, new policies were introduced to further criminalize every aspect of Black life. Super-maximum facilities were built to warehouse those who would be criminalized by these new policies. But prison administrators will never tell you this.

They will never tell you that incarcerated Black people are the only group of incarcerated people that are targeted based solely on perceived ideology. There is rarely any “activity” connected to the targeting – for validation – of an incarcerated Black person. They will never tell you that incarcerated Black people today are labeled “radical” solely based on the books we read.

This is the case today at Soledad, just as it was in the past. Fleeta Drumgo, for example, writes Yee, “kept some ‘Black books’ on his shelves, and was reported for it.” They will never tell you that, just like Allen Mancino was taken through the “tunnels” under the prison and intimidated, that just days after the raid here at Soledad on July 20, 2020, that incarcerated Black people were taken under the prison through the same tunnels and intimidated by officers in an effort to obtain “information.”

They will never tell you that the raid – and all the investigation, questioning, interrogation, and intimidation that resulted from it – was triggered by a “confidential informant,” who fed them bogus information in an effort to better his condition before he was transferred out of the prison – from O-wing – just days after the raid.

When we talk about prison abolition, we are talking about a holistic approach. We are talking about addressing all forms of harm – individual interpersonal harms, as well as systemic harms – patriarchal toxic Black male violence, as well as white supremacist capitalist imperialist patriarchy.

Our lawsuit, Williams et al. v. California Department Of Corrections And Rehabilitation et al., exposes the historical continuity of Soledad’s anti-Black racism.

Lastly, as Ida B. Wells expressed at the end of her statistical report, I ask for everyone to continue to support Black publishers, particularly the San Francisco Bay View, who have been supportive of not only this lawsuit, but my writing and the writing of incarcerated people in general.

If we don’t support us, who will?

I love you.

Send our brother some love and light: Marcelle (Talib) Williams, V69247, CTF-SP GW-346, P.O. Box 689, Soledad CA 93960.