Forged by decades of coalition building, the 2021 tribunal on U.S. human rights abuses stands as a powerful challenge to historical policies that have led to so much harm

by Jihad Abdulmumit, Nkechi Taifa and Matt Meyer

This article was originally published by Waging Nonviolence and Resistance Studies

Any movement worthy of serious consideration understands its historical precedents and the strategic contours of building from past realities towards future possibilities. The 21st century has so far been through some devastating crises, and while mass mobilization has been a feature of the past years, consistent, militant and revolutionary movements have yet to emerge.

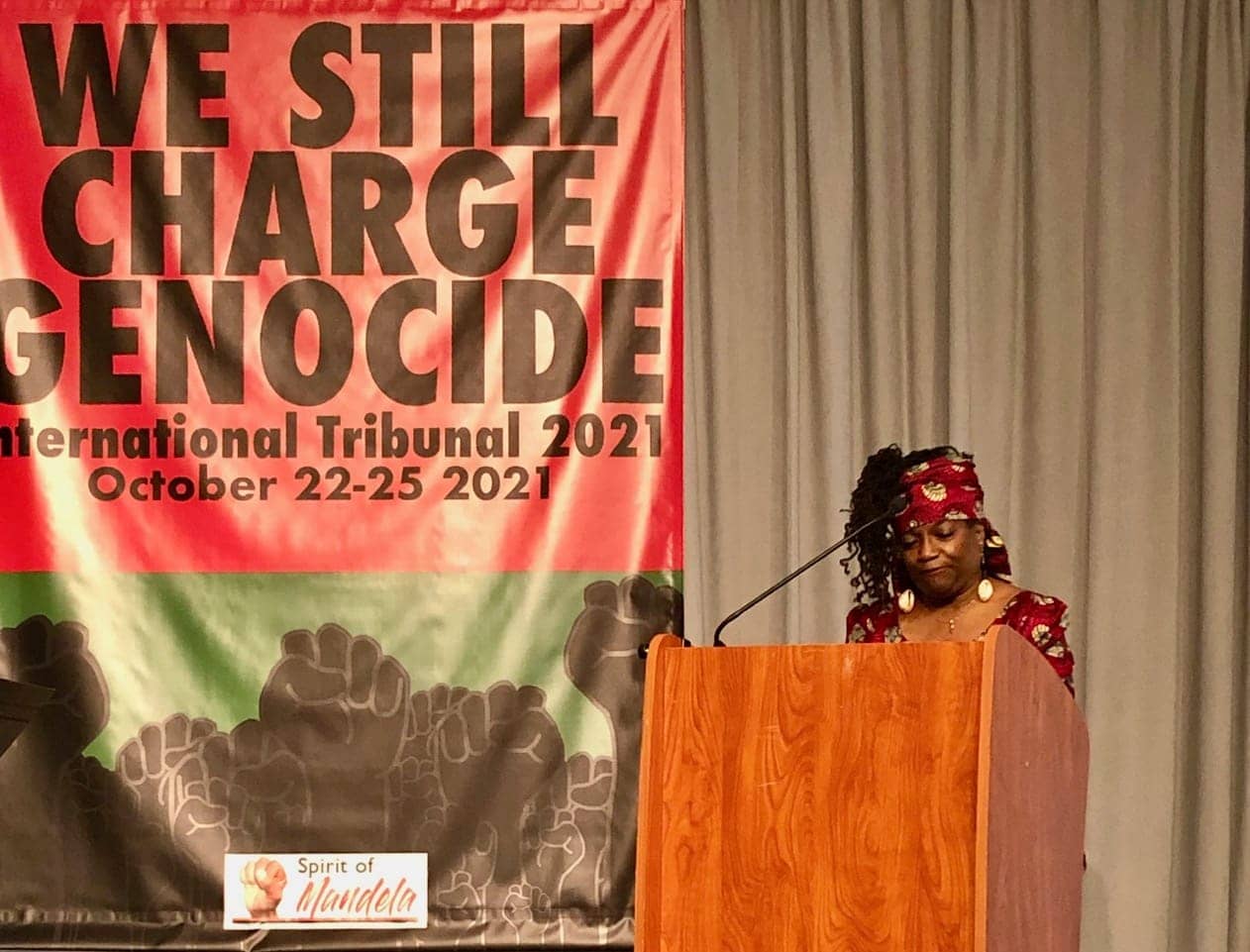

The call for a 2021 International Tribunal on U.S. Human Rights Abuses Against Black, Brown and Indigenous Peoples – based on international law and steeped in popular resistance – understood its place in history and the need to intensify all of our struggles, deepen our unity and increase our militancy, if any progress is to be made. Like the Sankofa bird of the Ghanaian Akan clan, we look back in order to understand how best to move forward.

70-year anniversary

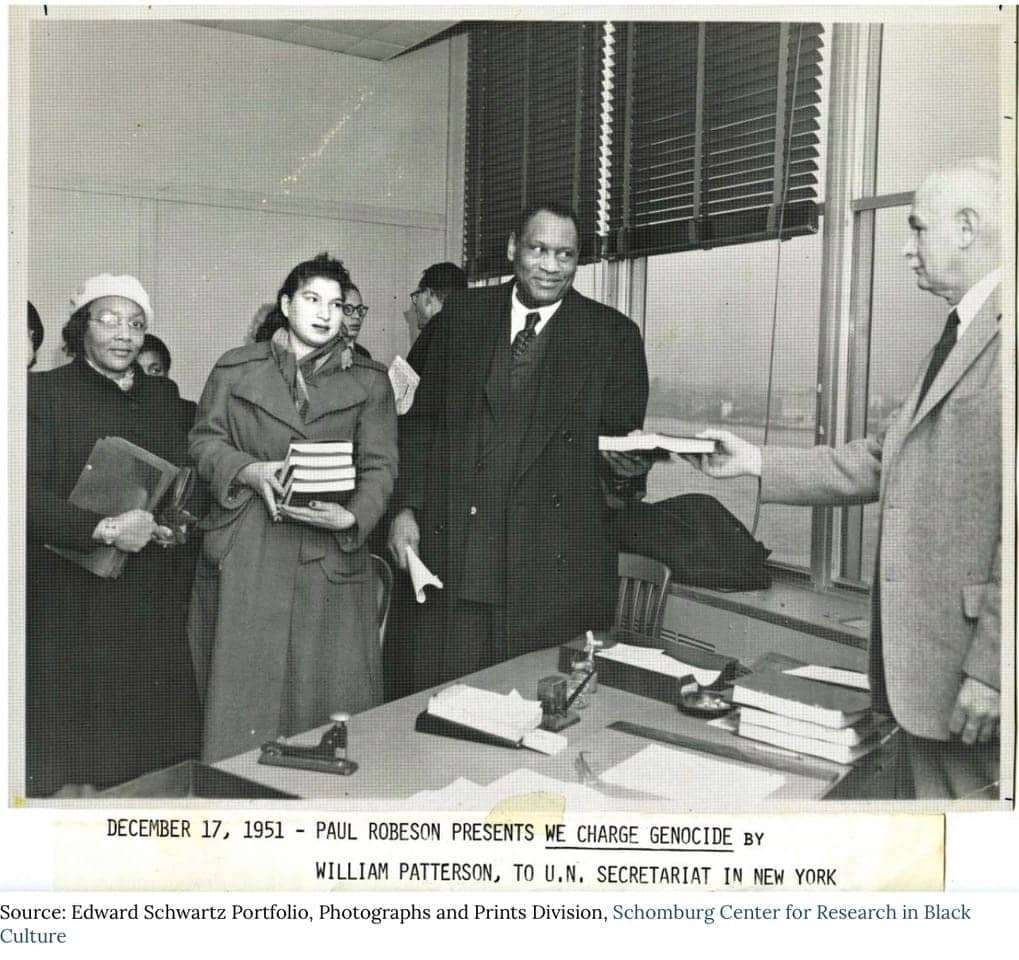

On Dec. 17, 1951, beloved actor, vocalist, athlete and activist Paul Robeson and organizer and attorney William Patterson submitted a petition from the Civil Rights Congress, or CRC, to the United Nations. Titled, “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People,” the petition was signed by almost 100 U.S. intellectuals and activists. Robeson led a delegation to present the document at U.N. headquarters in New York, while CRC Secretary Patterson delivered it to a U.N. meeting in Paris.

W. E. B. DuBois – preeminent sociologist, Harvard affiliate and co-founder of the NAACP – was scheduled to accompany Patterson to Paris, but the U.S. State Department prevented him from leaving the country.

The book-length petition documented hundreds of lynching cases and other forms of brutality and discrimination, evincing a clear pattern of government inaction and complicity.

It charged that in the 85 years since the end of slavery, more than 10,000 African Americans were known to have been lynched (an average of more than 100 per year), and that the full number can never be known because the murders were often unreported.

The authors of “We Charge Genocide,” taking from the U.N. statutes, therefore concluded that:

The oppressed Negro citizens of the United States, segregated, discriminated against and long the target of violence, suffer from genocide as the result of the consistent, conscious, unified policies of every branch of government. If the General Assembly acts as the conscience of mankind and therefore acts favorably on our petition, it will have served the cause of peace.

The founding of the 2021 Tribunal conceived, at its foundational stage, that the charge of genocide was more relevant than ever 70 years after the initial outcry. In 2017, several pivotal events pushed us forward in the concrete development of our current work. First, Black Liberation movement and Black Panther political prisoner Jalil Muntaqim, who co-founded the Jericho Movement and several other initiatives while behind the prison walls, wrote an essay noting that:

“In the Spirit of Nelson Mandela, we are calling for a new investigation by the International Jurists on the human rights abuses of political prisoners. It is incumbent on freedom-loving peoples of the world to join this campaign to expose this incessant racial repression by U.S. white supremacist practices on U.S. political prisoners.”

Also in 2017, a great victory occurred. Based on decades of strategic planning, grassroots education and organization and international alliance-building, Puerto Rican patriot Oscar Lopez Rivera was freed after over 36 years in prison. After years of petitioning the United Nations Committee on Decolonization and many other bodies, the 2016 U.N. committee members stated that they would visit Oscar Lopez directly if the U.S. did not accept the global calls for his release.

By the following year, the first speaker at the U.N. annual hearings, usually reserved for high level elected officials, was recently released Oscar Lopez himself, who received a standing ovation from international governmental and non-governmental representatives alike.

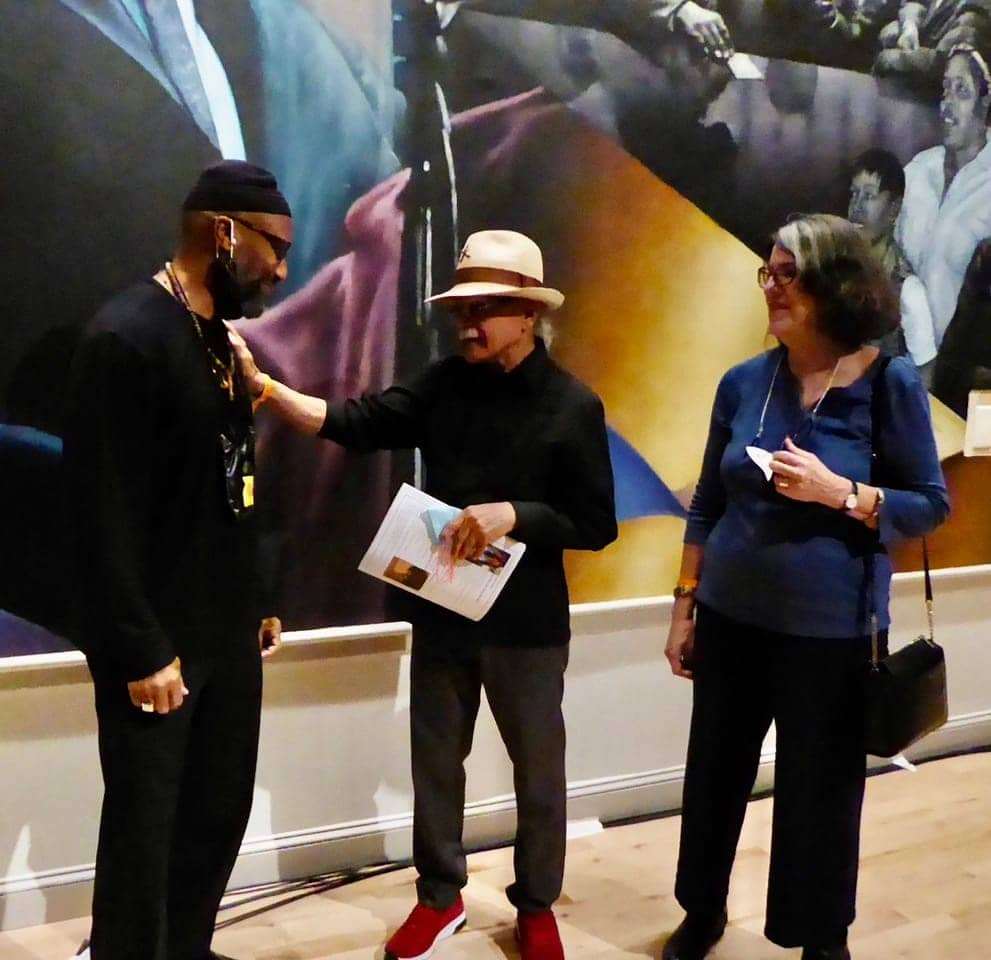

Among the participants were friend and recent-former political prisoner Sekou Odinga (a founder of the Black Panther Party International), Jericho Movement National Chair Jihad Abdulmumit and solidarity activist and author Matt Meyer (who had helped organize several tribunals throughout the 1990s and 2000s). Jihad Abdulmumit took the opportunity – in the halls of the U.N. assembly – to advance the idea of setting the date and creating a Tribunal organization. This would extend the parameters of the initial idea to include all forms of U.S. human rights abuses against Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples.

That vision could not have come about outside of the legacy of Minister Malcolm X, El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

Baba Sekou Odinga was a Queens-based youth when he first met Minister Malcolm. He later joined Malcolm’s exciting Organization of Afro-American Unity, or OAAU, based on the just-formed Organization of African Unity: a space for the newly independent nations of Africa to join together in Pan African development and peacebuilding.

“The U.S. government has taken elaborate steps to confuse world public opinion as to the true character of these prisoners, because their existence exposes deep injustices in U.S. society.”

Minister Malcolm and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. both increased their internationalist perspectives and actions in their final years, with Malcolm planning to utilize the OAAU to bring the case of U.S. human rights abuses against Black folks to the arena of the United Nations.

Minister Malcolm asserted:

“One of our first programs is to take our problem out of the civil rights context and place it at the international level, of human rights, so that the entire world can have a voice in our struggle. If we keep it at civil rights, then the only place we can turn for allies is within the domestic confines of America. But when you make it a human rights struggle, it becomes international and then you can open the door for all types of advice and support from our brothers in Africa, Latin America, Asia and elsewhere. So, it’s very, very important – that’s our international aim, that’s our external aim.”

Breaking silos within the U.S. left

In the late 1980s, a pivotal coalition was formed to plan for a major tribunal on U.S. political prisoners and prisoners of war, to take place at New York’s Hunter College in January 1990.

In the years leading up to the historic 1990 tribunal, a series of activities set the context for the transformative event.

Eminent Puerto Rican educator, sociologist and author Dr. Luis Nieves Falcon had relocated to New York City one year earlier to convene the effort, coming off of his successes in Barcelona, where the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal (derived from the Bertrand Russell Tribunals against the war in Vietnam) concluded that Puerto Rico’s ongoing colonial status required immediate global attention.

Over a thousand participants gathered at Hunter College from around the world, mingling with groups and leaders from various national liberation movements within the U.S. The tribunal was a serious political-judicial undertaking; legal documents were carefully drawn up in accordance with international law, statutes and precedents.

An indictment was written and delivered to U.S. officials, who were invited to attend and defend. An international panel of judges with distinguished legal and civic credentials was assembled.

The tribunal itself was only the capstone of a carefully orchestrated set of multifaceted events throughout 1990. A large-scale poetry reading was held at New York’s prestigious Society for Ethical Culture; an art show was presented at Charas, a progressive community center; and an interfaith summit was convened at the American Indian Community House. The tribunal itself became a hot ticket, public political event.

By the end of it all, the issue of political prisoners was more clearly and definitively on the agenda of the U.S. left, and a verdict was available for the various movements to use in their base-building work.

Dr. Falcon, in preparatory essays before the tribunal itself, noted that:

“The U.S. government has taken elaborate steps to confuse world public opinion as to the true character of these prisoners, because their existence exposes deep injustices in U.S. society. Furthermore, behind the screen of secrecy the jailers hope to break the prisoners’ bodies and spirits before an international conscience moves in a solidarity effort to demand an end to these abuses and for their immediate freedom.”

“Before we can move ourselves, we have to change our hearts, and if we change our hearts, we can move other people because the human heart is universal, the human spirit is universal!”

In the unique New York setting, prominent Columbia University anti-apartheid activist, Tanaquil Jones, had befriended and then married well-known Panther prisoner Dhoruba bin-Wahad, whose dramatic release on his own recognizance – scarcely six months before the start of the tribunal – aligned the two of them with the central organizing efforts.

“Our fight is essentially a work of the heart and spirit,” Dhoruba noted in a pre-tribunal event. “Back in the days of the [Panthers]…we didn’t realize that it was the subjective factor that was the dynamic factor. Before we can move ourselves, we have to change our hearts, and if we change our hearts, we can move other people because the human heart is universal, the human spirit is universal!”

Tribunal Chief Prosecutor Nkechi Taifa, author of “Black Power, Black Lawyer” was one of the many legal minds who assisted in the background work of the 1990 effort. Having worked closely as a young woman with Imari Obadele, the first popularly elected president of the provisional government of the Republic of New Afrika, she was well steeped in the history of positive liberation efforts. As part of the crusade of the New Afrikan Independence Movement to get Black political prisoners and prisoners of war recognized, both domestically and internationally, Taifa had both the organizing and the judicial skills to take on the lead role in the 2021 tribunal, looking more widely at human rights beyond the prison walls.

In a statement leading up to the tribunal, she strongly asserted:

“There is no need to invent any new wheels. There is precedent for our Tribunal actions. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted reparations to Japanese Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, explicitly included a pardon for all those who resisted detention camp internment. No reconciliation or community peace can be expected until these basic demands, addressing fundamental injustices in recent history and memory, are seriously and significantly addressed.”

The U.S. found guilty? What’s new and what’s next

There are barely two years remaining of the International Decade for People of African Descent. For centuries People of African Descent in the U.S. have not only dreamed of justice but demanded it. We have urged the country to provide not even grandiose opportunities, but just basic human rights that protect our life and liberty.

The response, however, has been systemic racism through which we suffer through decreased life expectancy rates, health disparities, economic inequality, mass incarceration and more.

Tragic as it was, the explosion resulting from George Floyd’s death represented only the tip of Black people’s demands for justice. The U.S. government has failed to protect Black people from systemic racism and police violence.

The international community must bear witness. The U.S. must not be above scrutiny. It must meet its commitments, review its own record, be open to criticism and rectify injustices. Similarly, the U.S must fully embrace human rights conventions it is a party to and eliminate limitations to their use in U.S. courts.

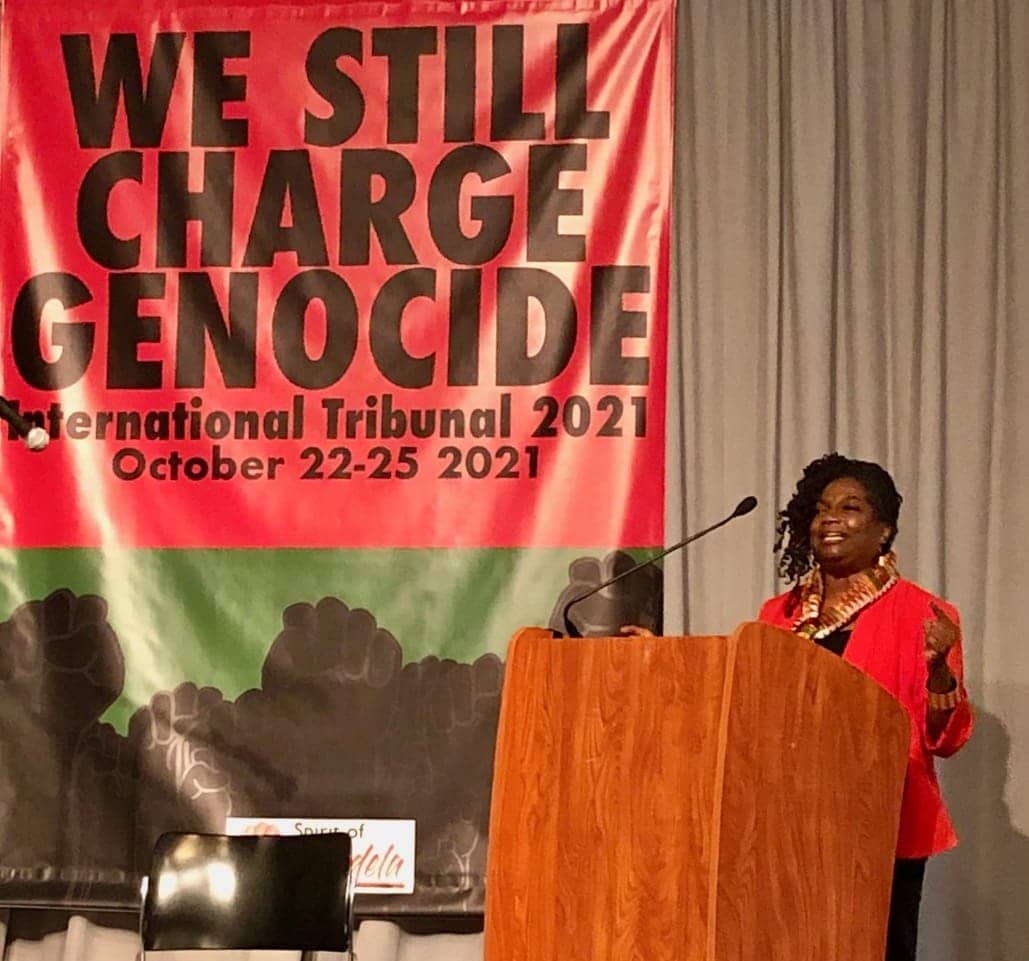

The October 2021 International Tribunal stands as a powerful and viable tool in the people’s movement to challenge and eradicate the historical policies that have led to so much harm.

What is so significant about the Genocide Convention to activists, advocates and lawyers is that it is the only international human rights treaty adopted by the United States that is fully actionable in U.S. law. Later international human rights treaties, such as CERD, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention Against Torture, while symbolic, are not self-executing, meaning they are not enforceable in U.S. courts because there is no U.S. legislation to implement their provisions.

Ratification of the Genocide Convention, however, required the adoption of implementing legislation, to ensure that the ratification not be a symbolic gesture, but have the full force of law and the authority to enact penalties.

Testimonies within the tribunal showed beyond any doubt that the U.S. violates not only elemental principles enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, but basic human rights and fundamental freedoms outline in a myriad of international instruments as well. The October 2021 International Tribunal stands as a powerful and viable tool in the people’s movement to challenge and eradicate the historical policies that have led to so much harm.

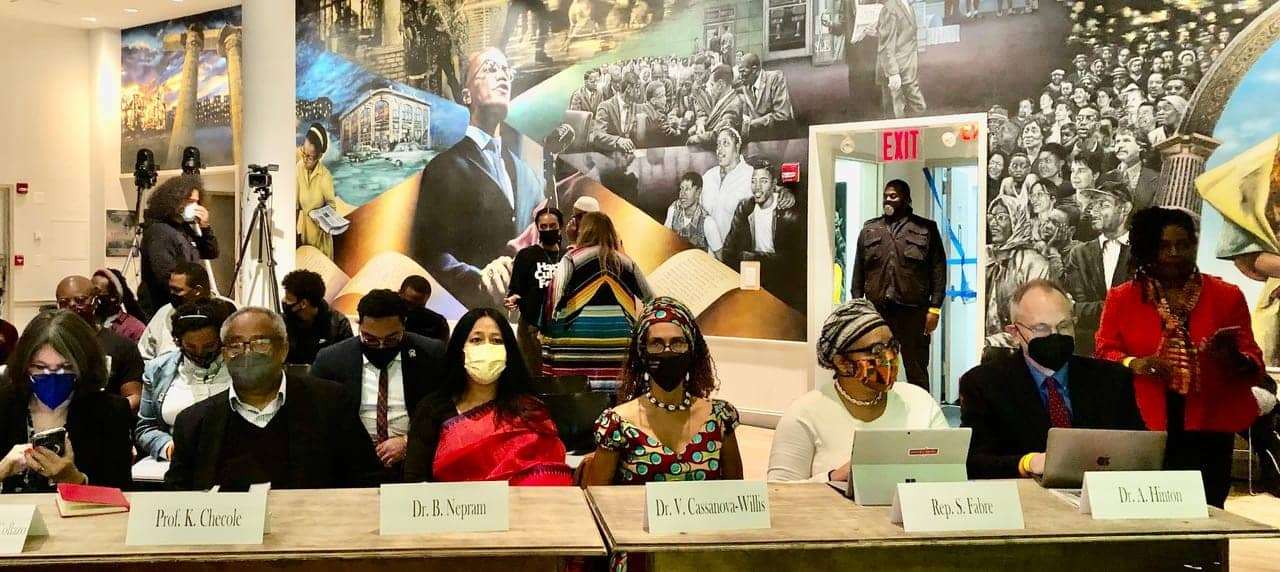

When the esteemed panel of jurists released their preliminary verdict on Oct. 25, 2021, they answered the 70-year call: The U.S. was guilty of genocide on five basic charges. The jurists included nine independent and unimpeachable human rights experts: a South African former member of parliament, a representative of Nobel Peace laureate organization International Peace Bureau, a U.N. liaison from the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, the UNESCO Chair on Genocide Prevention, a former Chair of the U.N. Working Group on People of African Descent, a leader of the Puerto Rican Bar Association and others. With messages of support from the progressive governments and the daughter of Winnie and Nelson Mandela herself, the message was literally heard around the world.

We do not believe in coincidences. It was therefore shocking but not surprising that, just hours before the final press conference of the 2021 Tribunal, the news of the eminent release of one of the most beloved Black political prisoners hit the airwaves. Less than two days later, Russell Maroon Shoatz – survivor of over 22 consecutive years in solitary confinement and 48 years behind bars – was home at his sister’s house, receiving medical treatment and the love of his family.

In that same two-day period, anti-racist political prisoner David Gilbert – who merely two months prior was not to be even eligible for parole until his 112th birthday – was granted parole and ultimately home by the winter holidays.

This is not to suggest that the tribunal was some magic “get out of jail free” card. Both Maroon and Gilbert had long-standing and extensive support committees and campaigns. But it would be equally naïve to think that certain strategic orientations, ones that include both legal interventions and political pressures, both behind-the-scenes appeals to those in power and more overt threats of public shaming of politicians, cannot make some very real differences.

The added fact that a major global initiative, with an independent panel of jurists with high-level human rights credentials, was taking place to consider the case of U.S. political prisoners in the overall context of U.S. acts of genocide, should also not be overlooked.

It is simple historical fact that the U.S. government, in addition to fearing the rise of people’s movements (especially ones led by Black radicals like original Panthers and their descendants), has also been petrified of having its domestic injustices given international spotlight.

Therefore, we look towards the future with guarded hope. As we continue to build careful points of unity among the diverse elements of the Spirit of Mandela coalition, and as we plan for a cross-continental, representative “People’s Senate” to emerge as a counter to the unrepresentative electoral college or Washington D.C.-based “houses” – which have done far worse than simply failing to stop abuses – we will use every tool we can find.

The tactics of international shaming, combined with massive educational efforts, creative legal initiatives and grassroots, community-based resistance campaigns all have a crucial role to play. In the spirit of past people’s victories – including the U.S.-based Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker – we must work together more closely and with passion, because the alternatives are unthinkable.

Jihad Abdulmumit of the 2021 International Tribunal Coordinating Committee is also chairperson of the National Jericho Movement. He is a playwright, with a theater company called For Our Children Productions.

Nkechi Taifa is a lawyer, activist and CEO of the social justice-centered consulting firm Taifa Group. Nkechi Taifa served as chief prosecutor for the 2021 International Tribunal.

Matt Meyer is author of numerous books on resistance and social change chiefly published by PM Press and Africa World Press. He is the secretary general of the International Peace Research Association, a long-time leader of both the War Resisters League and Fellowship of Reconciliation, the senior research scholar of the Resistance Studies Initiative and an advisory board member of Waging Nonviolence.