by Linn Washington

When Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Lucretia Clemons released an inmate from prison in May 2021, she clearly saw how prosecutors illegally withholding evidence of innocence caused that Philadelphia man to languish in prison for nearly 30 years on a wrongful murder conviction.

As Clemons released Eric Riddick from prison on May 28, 2021, she declared that misconduct by Philadelphia prosecutors against Riddick constituted a “constitutional violation.”

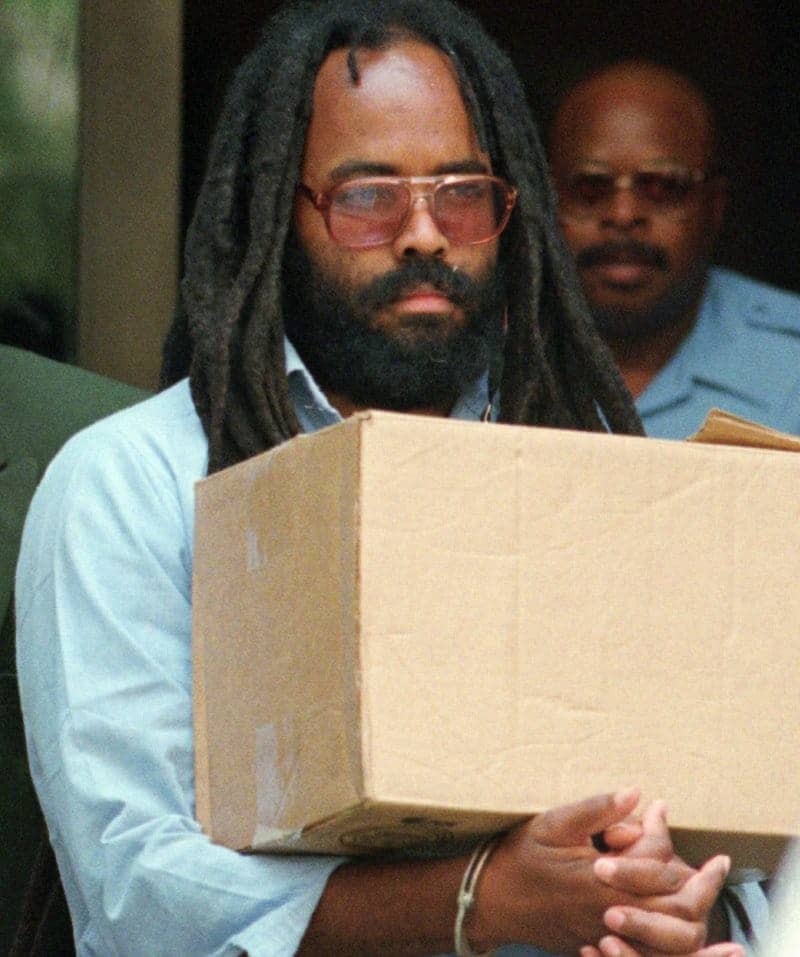

Yet, 96 weeks later, Clemons refused to see gross constitutional violations by Philadelphia prosecutors in the controversial case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the Philadelphian whose murder conviction 41 years ago is condemned as wrongful by millions around the world.

On March 31, 2023, Judge Clemons issued a ruling on the latest appeal filed by Abu-Jamal where she rejected claims that materials in six boxes on the Abu-Jamal case withheld by prosecutors for 36 years constituted a constitutional violation like the violation she acknowledged in the Riddick case.

This recent ruling by Clemons dismissed the core issue in Abu-Jamal’s appeal: fundamental damage done to Abu-Jamal’s defense by prosecutors who withheld evidence that undermined their case for decades. Prosecutors misled judges with claims that they released all information to Abu-Jamal’s lawyers.

The evidence withheld by prosecutors that Judge Clemons refused to fault involved constitutional violations that judges in Pennsylvania (and across America) are duty bound to correct to ensure justice. The introduction (preamble) to Pennsylvania’s Code of Judicial Conduct states judges serve “a fundamental role in ensuring the principles of justice.” Clemons’ Abu-Jamal ruling evidenced an abdication of her role to ensure justice.

Sophisticated lawlessness

Judge Clemons’ studious suffocation of Abu-Jamal’s appeal involved her failure to fully embrace the correct injustice intent underlying two famous U.S. Supreme Court rulings, known widely as Batson and Brady.

The Batson ruling, issued by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1986, essentially bars prosecutors from excluding jurors based solely on their race.

A document in those six withheld boxes revealed the prosecutor at Abu-Jamal’s 1982 trial tracked the race of potential jurors. For decades, Philadelphia prosecutors denied such tracking took place during Abu-Jamal’s trial.

Abu-Jamal was tried before an overwhelmingly white jury despite Philadelphia having a 40 percent African American population at the time of his 1982 trial.

Clemons termed Abu-Jamal’s claims of damage from the withholding of the trial prosecutor’s jury selection notes “baseless.” Additionally, Clemons stated Abu-Jamal had “no right” to that prosecutor’s notes because of court rules.

The Brady ruling – issued by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1963 – requires prosecutors to provide defendants with all evidence of innocence and guilt in their possession. Brady requires prosecutors to disclose this evidence in a timely manner. The nearly 40-year time span that Philadelphia prosecutors withheld those six boxes of material from Abu-Jamal’s attorneys is far beyond even the most elastic deference to Brady’s “timely disclosure” requirements.

The Brady evidence in those six boxes further tainted the already questionable testimony of the two prime witnesses against Abu-Jamal at his 1982 trial.

Legal sophistry

The correct wrongful conviction requirements of the Batson and Brady rulings are baked into Pennsylvania criminal law procedure. Judges across Pennsylvania have granted new trials based on Batson and Brady violations. Those violations led to releases from prison, including directly from death row.

Brady requirements, for example, are found in rulings by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, rules for prosecutors established by the state’s Supreme Court and requirements for lawyers in the Pennsylvania code that lists all rules, regulations and documents from the government of Pennsylvania.

The Pennsylvania Rules of Professional Conduct for lawyers contains a section entitled “Special Responsibilities of a Prosecutor.” That section (3.8d of the rules) requires prosecutors to “make timely disclosure to the defense of all evidence or information known to the prosecutor that tends to negate the guilt of the accused or mitigates the offense.”

The appeal documentation Clemons rejected included meticulous details of requests from Abu-Jamal’s lawyers over the decades for Brady material, material prosecutors persistently failed to release. Prosecutors claimed in court that they released that requested information but did not. Some of that information was released months, years and decades later. It’s unclear today if prosecutors have released all Abu-Jamal information in their possession.

Judge Clemons claimed with crystal-ball clarity that Brady evidence withheld for 36 years would not have convinced the trial jury to find Abu-Jamal not guilty. Further, Clemons claimed that withheld evidence of Batson issues by the trial prosecutor was not a violation that she could address.

Rules run amuck

Clemons, throughout her rejection of Abu-Jamal’s appeal, deftly used court rules to eviscerate the relief Abu-Jamal is lawfully entitled to receive.

Clemons’ rejection repeatedly referenced rulings by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania against Abu-Jamal as authority with no reference to that court’s record of bias against Abu-Jamal. The February 2000 report on the Abu-Jamal case by the respected Amnesty International contained concerns about entanglements between Pennsylvania’s highest court and anti-Abu-Jamal forces within law enforcement, particularly Philadelphia’s police union.

That Amnesty International report noted, “The Court’s own rulings on Abu-Jamal’s appeals have left the unfortunate impression that the state Supreme Court may have been unable to impartially adjudicate this controversial case.”

The December 2022 submission to Clemons from the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent reminded this judge of the necessity to examine “racially discriminatory effects and biased decision-making.” That submission declared examination was relevant irrespective of courts often being “hesitant to disturb prior decisions.” Clemons rejected that reminder.

Prosecutorial hypocrisy

Compounding the travesty of Clemons’ abdication of her judicial duty to correct injustice is the persecutive posture of Philadelphia’s “progressive” District Attorney Larry Krasner. He is the person who personally found those six boxes of evidence withheld by previous prosecutors for 36 years. Krasner stumbled on those boxes, stashed in a storage room, during a walk-about of the DA’s multi-floor office space in 2018.

Krasner is a harsh critic of prosecutorial misconduct, including prosecutors illegally withholding evidence. In June 2021, Krasner’s office released a report on prosecutorial misconduct by his predecessors. In the “By The Numbers” section of that report, it stated in the 21 exonerations secured by Krasner’s staff between January 2018 through June 2021, 20 of those 21 cases involved prosecutors withholding “exculpatory evidence” – evidence of innocence. Fifteen of those 21 cases included misconduct by police. Misconduct by prosecutors and police are pivotal issues in the Abu-Jamal injustice.

Although Krasner in that 2021 report stated prosecutors have a “sworn oath … to seek justice unconditionally, with no limit as to time,” Krasner’s office vigorously opposed Abu-Jamal’s latest appeal. Krasner’s prosecutors utilized the same fact-fudging, anti-Abu-Jamal postures as his predecessors.

Arguments against Abu-Jamal’s appeal by Krasner’s office included claims that some of the evidence in those six boxes could not be used in court because that material was “time barred.” Krasner’s prosecutors argued that Abu-Jamal raised issues about that evidence too late for use in court even though Abu-Jamal did not know that evidence existed because it was withheld by prosecutors.

Krasner failed to follow his stated position that prosecutors must seek justice with “no limit as to time.”

Obvious wrong overlooked

One of the documents withheld from Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for three-plus decades is a letter sent to the prosecutor at Abu-Jamal’s 1982 trial from that prosecutor’s prime witness against Abu-Jamal. In the letter, that witness demanded the “money” he said the prosecutor – Joseph McGill – owed him. Abu-Jamal argued that demand for money referenced an improper payment to that witness promised for his trial testimony.

Weeks before sending that letter, this witness – Robert Chobert – told jurors that he saw Abu-Jamal kill a Philadelphia policeman on Dec. 9, 1981. Chobert’s key testimony helped produce Abu-Jamal’s conviction and initial sentence to death row.

Under the Brady doctrine, the indisputable fact that prosecutors withheld this evidence of arguable impropriety gave Clemons the authority to release Abu-Jamal directly from prison, grant him a new trial or at least order an evidentiary hearing.

During an evidentiary hearing, McGill and Chobert would testify under oath about the true meaning of that money-demand letter. The ruling by Clemons rejected both an evidentiary hearing and a new trial, thus continuing Abu-Jamal’s unjust imprisonment.

An aspect of Clemons’ ruling embraced a written statement from now ex-prosecutor McGill where he endorsed the honesty of Chobert yet admitted he misled Chobert.

Clemons, in her ruling, gave weight to McGill’s affidavit where that ex-prosecutor claimed the money demand from Chobert concerned a request for wages the cab driver said he lost while participating in Abu-Jamal’s trial.

McGill, according to Clemons’ ruling, told Chobert he would inquire about providing the claimed lost wages. But McGill quickly declared in his affidavit that he “had no intention of looking into the compensation issue.” McGill’s affidavit stated DA office policy barred compensating witnesses for “lost wages.”

Since Chobert’s money demand supposedly did not involve payment for testimony, it raises questions as to why McGill didn’t simply tell Chobert that such compensation was against DA office policy instead of stringing Chobert along with stating he’d inquire about lost wages.

Incredibly, Clemons declared the non-disclosure of that money-demand letter did not harm Abu-Jamal’s legal rights. Clemons claimed that even if Chobert confirmed a payment for testimony scheme, “that admission would not be sufficient to” help Abu-Jamal.

“Therefore, the Defendant’s Brady claim about Chobert lacks merit,” Clemons stated in her rejection.

Defending the indefensible

While Clemons quoted heavily from Chobert’s testimony against Abu-Jamal, she curiously did not reference critical context about Chobert.

Clemons omitted facts that Chobert was on probation for firebombing a school and he was illegally driving a cab because of suspension of his license for DUI. Clemons also ignored another damning aspect about Chobert. Photographic evidence shows Chobert was not where he claimed he saw the fatal shooting. A policeman’s report about Chobert, in those six boxes, confirms that lack of photographic evidence.

The 1982 jury never heard those damning facts about Chobert due largely to rulings by the trial judge – the late Albert Sabo.

Sabo, days before Abu-Jamal’s trial, declared his intent to help prosecutors “fry the nigger.” That was clear evidence of racial and pro-prosecution bias by Sabo, but that statement was ruled harmless by Pa state and federal court judges.

The jury never heard that Chobert thought during the 1982 trail that McGill would help get his driver’s license reinstated. This is another fact Clemons noted in her ruling but found unpersuasive in shaping Chobert’s testimony. Clemons gave added credence to Chobert because he testified against Abu-Jamal during a 1995 proceeding despite not having his license restored.

Clemons never referenced the fact that Chobert told investigators for Abu-Jamal in the early 1990s that he was not where he claimed he was during his court testimony in 1982. Chobert told others the same thing over a decade later.

Justice denied again

The fact that DA Krasner fought to free many falsely imprisoned persons due to prosecutorial misconduct yet fought to block lawful relief for Abu-Jamal evidences the institutional animus against Abu-Jamal exhibited by police, prosecutors and judges since Abu-Jamal’s arrest on Dec. 9, 1981.

This ruling by Clemons perpetuates the pattern of willful participation in the institutional animus against Abu-Jamal by judges.

Rule 2.3 of Pennsylvania’s Judicial Conduct Code declares, “A judge shall perform the duties of judicial office … without bias or prejudice.”

For many, this ruling by Clemons is contrary to the judicial duty to ensure justice.

Where Clemons saw wrong in the case of Eric Riddick, she refused to see what was right, lawful and required in the Mumia Abu-Jamal case.

Linn Washington, a professor of journalism at Temple University and award-winning columnist for the Philadelphia Tribune, has covered Mumia Abu-Jamal’s fight for freedom from the beginning, in December 1981. This story first appeared on This Can’t Be Happening, the website featuring the work of a news collective comprising Linn Washington and three other renowned journalists. They can be reached at thiscantbehappeningmail@yahoo.com.