by JR Valrey, the People’s Minister of Information and editor in chief of the SF Bay View

Last month, we began a series of articles talking to the legendary movement photographer Jeffrey Blankfort, who photographed the Black Panthers after the murder of Lil Bobby Hutton. He photographed the ‘68 Olympics in Mexico City, as well as the International Section of the Black Panther Party in Algiers. He has a number of stories surrounding these incidents that have never before been documented in the Black press.

It is important for the Black community to preserve its own revolutionary history so that it is not omitted or revised when these historical scenarios are presented to the public. Jeffrey Blankfort is a non-Black longtime ally of the Black freedom and self-determination struggle, who has done solidarity work within Black communities for several decades.

In this part of the series, Jeffrey Blankfort is talking about being a photographer for the San Francisco based lefty mag Ramparts and covering the Black Panther Party’s International Section in Algiers, Algeria. He also talks extensively about going to the ‘68 Olympics and covering it as a photographer.

JR Valrey: How did you become a writer at Ramparts Magazine? Where was the magazine located?

Jeffrey Blankfort: Well, to start with, the magazine’s office was in a two story building on Broadway in San Francisco’s North Beach, a few blocks east of Columbus and close enough to the area’s best restaurants to make full use of Ramparts’ Diner’s Club and Carte Blanche credit cards.

I actually wrote only one story for Ramparts but it turned out to be a unique one, and was later honored for being so. Early in 1969 I read a short article in the San Francisco Chronicle about a small town in Ohio, Beallsville, with a population of 500, that had lost five of its sons in Vietnam and petitioned the government not to send any more of them to fight in that war since they were losing an entire generation,

The “Defense” Department, as could have been expected, turned the town down. Upon seeing the story I asked the editors at Ramparts to send me to Beallsville to interview the parents of the soldiers who had died and so, despite some misgivings on the part of one of the editors, they agreed.

After getting the names of the war dead from a waitress at a coffee shop in the nearest small town – everyone seemed to know each other in those parts – I began interviewing the dead boys’ parents and found almost as many opinions about the war among them as the number who died. As it turned out and what I still find incredible is that, according to the Library Association of America, which included the story in its anthology, “Reporting Vietnam,” mine was the only interview of parents of U.S. soldiers who died in that war to appear in any American magazine.

The story was well received, but the appraisal I most appreciated came in an unexpected place from an unexpected source. When I visited Paris in 1973 and was introduced by a friend to one of the major figures in North Vietnam’s peace negotiating delegation as being with Ramparts, he smiled and recalled the story and was pleased, four years later, to meet its author.

JR Valrey: What was your relationship like with Eldridge Cleaver, who also wrote for Ramparts and became the Minister of Information of the Black Panther Party?

Jeffrey Blankfort: Eldridge and I had a friendly relationship while he was living in San Francisco but most of my contacts with the party then were with Kathleen, who was putting out the newspaper. I came to know him better when I visited Algiers in December 1970, where he headed the International Section of the Black Panther Party, and later in 1973 after he and Kathleen had moved to Paris.

Algiers, at that time, could have been described as the international headquarters for all of the world’s liberation movements and the Panthers were considered by the government of Algeria and the other liberation struggles to be the legitimate representatives of the Black liberation struggle in Babylon, which is how Eldridge and many other Panthers referred to the USA. Eldridge and other Panthers there, among them the late Donald Cox (DC), Sekou Odinga and Pete O’Neal, regularly met with representatives of the other movements, which helped give the party an unparalleled status worldwide.

One critical mistake that Eldridge made was offering sanctuary to Tim Leary, the psychedelic guru, who had been sprung from prison by the Weathermen. Eldridge had this idea that Leary could become the link between the white anti-war movement and the dopers into psychedelics. Having previously witnessed Leary’s behavior, I strongly disagreed and told him it wouldn’t work.

Eldridge insisted that his plan was working, that he had an Algerian writer, psychologist and veteran of the liberation struggle against the French doing a series of interviews with Leary that indicated he was, so to speak, coming on board, politically. Shortly after I arrived there with two friends from Mexico, one an American, both strong supporters of the Panthers, Eldridge told me that the final interview with Leary would take place that night and he wanted me to be there taking photos.

It was a disaster. Leary, seeing that two of us were Americans, mistakenly believed that we were into his psychedelic trips into unreality and he abandoned everything he had said in the earlier interviews, reverting to the nonsense he had been peddling for years back in the States.

Leary, for me, was the kind of con man who would say whatever he thought his listeners wanted to hear, and that night he guessed wrong bigtime. Not only were his Algerian interviewer, Moktar Moktefi, and his American translator, Elaine Klein, furious with his responses, but it was clear from the look on my face and the vibes coming from my friends off to the side. It became clear to Leary that he had badly misjudged his audience. He began to sweat bullets and at one point put his left arm behind the back of his chair as if it was being held there and he was a prisoner being interrogated.

In order to allow Leary into the country, Eldridge had to guarantee that Leary would not take any psychedelic drugs and Leary had agreed. Shortly after we left, however, a delegation from Berkeley led by Stuart Albert arrived, bringing acid for Tim which they proceeded to partake in public, something you just don’t do in Algiers. As a result and to preserve the Panthers’ situation there, Eldridge put Leary under “house arrest.”

Jumping ahead to March of 1971, and I am just back in the U.S., and I have traveled from New York to attend an anti-war conference at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Upon my arrival at the event, I am greeted by the well-known Berkeley activist, Jerry Rubin, accompanied by his pal, Abbie Hoffman. Seeing me, Jerry, a close friend of Stu Albert, raised his fist in the air and shouted, “Free Tim!”

No, no, Jerry, I tell him, you’ve got it all wrong and tried to explain what I had learned about Leary’s dropping acid in public. It doesn’t work with either him or Hoffman who tell me they are planning to introduce a resolution at the conference condemning Eldridge and the Panthers for imprisoning Leary. To stop that nonsense from happening, I turned to some local activists who were able to convince the two to keep their mouths shut.

In the summer of 1973, I was in Paris, as I mentioned earlier, where Eldridge was seeking political asylum from the French government to stay there, and he and Kathleen, with the help of friends, including Ellen Wright, widow of writer, Richard Wright, had found a comfortable apartment, albeit with police stationed on the street below from early morning to midnight, which I visited a number of times. Although he had learned French and enjoyed the pleasures of the city, Eldridge clearly missed Babylon, which explains a number of things he would later do to come back to the U.S. without being thrown in jail for jumping bail.

JR Valrey: What did you think of the journalism within the Black Panther newspaper, be it that you worked in the non-Black alternative press?

Jeffrey Blankfort: The Panther paper, and particularly, the art work of Emory Douglas, now a world recognized artist on the basis of what first appeared in The Black Panther, emphasized the resistance of the Black community, adults to children, to the prevailing racism of America’s cities and the police, referred to as “the pigs” who enforced it. One still can’t look at Emory’s images from back in the day without feeling, once again, of being drawn into the struggle.

The paper, itself, also carried hard-hitting stories of resistance to injustices, locally and globally, that many, if not most of the white alternative press ignored.

JR Valrey: How did you get the assignment from Ramparts to cover the 1968 Olympics? How did you get the press credentials?

Jeffrey Blankfort: Ramparts’ editors, who I had come to know, had been pleased with my earlier photos of the Panthers and the Democrats’ convention in Chicago that August, so assigning me to cover the Olympics was to be expected. But actually, I was sent there to cover more than the Olympics. Shortly before the beginning of the games, there had been weeks of protests against the Mexican government by workers and students. On Oct. 2, 10 days before the launch of the Olympics, the Mexican army attacked a mass rally of students in the ancient stone plaza of Tlatelolco, surrounded on all four sides by middle class high rise apartments.

The massacre, it seems, had been initiated by Mexican army snipers against their fellow soldiers who supposedly believed that they were being fired on by the students, none of whom were armed, but what I heard years later from a son of one of the soldiers, a student at Richmond High, who defended his father’s actions, was that the army, drawn from the ranks of Mexico’s poorest, saw the students as their class enemy, a view that evidently had been pushed by the government.

The exact number of dead, estimated at 400, has never been acknowledged nor the number wounded or arrested which reportedly was in the hundreds. The Mexican government and the U.S. mainstream media, hoping not to discourage attendance at the Olympics, originally reported the death toll as 14.. The higher death total, I later learned, included two students whose contact information was provided to me before I left for Mexico, but we never had the chance to meet.

I had planned to be there to take not just still photos but, with a 16mm film camera, provided by Universal Studios, which wanted footage for a mainstream movie on the ongoing political movements, “Zabriskie Point,” then being directed by the Italian filmmaker, Michelangelo Antonioni, whose American assistant told me that if I was clubbed or shot at the rally and was falling, “to keep shooting.”

Fortunately, I had to postpone my flight and arrived two days later and was more than a little concerned when a photographer waiting on the tarmac took my picture, and only my picture, before turning and walking away – and when the desk clerk at the hotel asked where I was staying, he seemed to know I was a journalist when I checked in, without my having mentioned that when making my reservation.

As for Ramparts coverage of the rally and the massacre, it was an embarrassing misadventure. The popular New York columnist, Jimmy Breslin, with impressive “progressive” credentials, who the magazine had hired to write the story, spent most of his times in local bars, and missed basic facts of the event beginning, with his description of the modern apartments of Tlatelolco as a “slum.” Clearly, he had never even bothered to visit the site.

Getting my press credentials, I naively expected, wouldn’t present a problem. When I saw a notice for a meeting of U.S. sports writers, I entered the room where I was pleased to see several track and field writers from the Los Angeles papers who had been personal friends and occasional drinking buddies when I had worked at the Los Angeles Examiner back in the ‘50s while attending UCLA. They were not pleased to see me and, so it seemed, considered me a traitor. That I was there for Ramparts clearly was no secret, and the head of the U.S. Olympic press corps, Don Paul, made that clear when I went with the others to pull a U.S. press cap out of the box in the front row. “Not you, Blankfort,” he said emphatically. I realized at that moment that I was on my own.

As I explained in our previous interview, I decided to go right to the top to get a press credential, to the head of the Mexican Olympic Games, Jose Cuervo, and two days later, I obtained an appointment with him at 2 a.m., that’s two in the morning. He was obviously a busy guy. I told him how the U.S. was denying me a press pass because it opposed Ramparts’ efforts to expose U.S. racism, with which I assumed, correctly, he would be sympathetic. He was and told me to get a telegram from Ramparts confirming my assignment and I would have my credential the next day.

In this process, I had to work around his chief assistant, a white South African who was in no mood to help me. So the next day, after contacting Ramparts and had returned to Cuervo’s very large outer office, I was both stunned and relieved to see the telegram from Ramparts editor, Robert Scheer, acknowledging me as representing the magazine, stunned to see it just lying around on a desk and relieved to find it. Since Cuervo was not in his office where I could let him know it had arrived, I called another number he had given me.

As I sat at a desk and dialed that number, the South African put his hands on my shoulders to get me to leave. By the best of luck, Cuervo quickly answered my call and when I told him the telegram had arrived, he told me to pick it up from the South African the next morning. Then I turned to that South African – Peter Selliers was his name – and handed him the phone. “It’s your boss, Señor Cuervo,” I said.

The credential, with no country listed, was waiting for me the next day. It was only later that I learned from a Czechoslovakian woman who worked in the same office that the South African had 40 soldiers on the floor below ready to arrest me if I refused an order of his to leave the office.

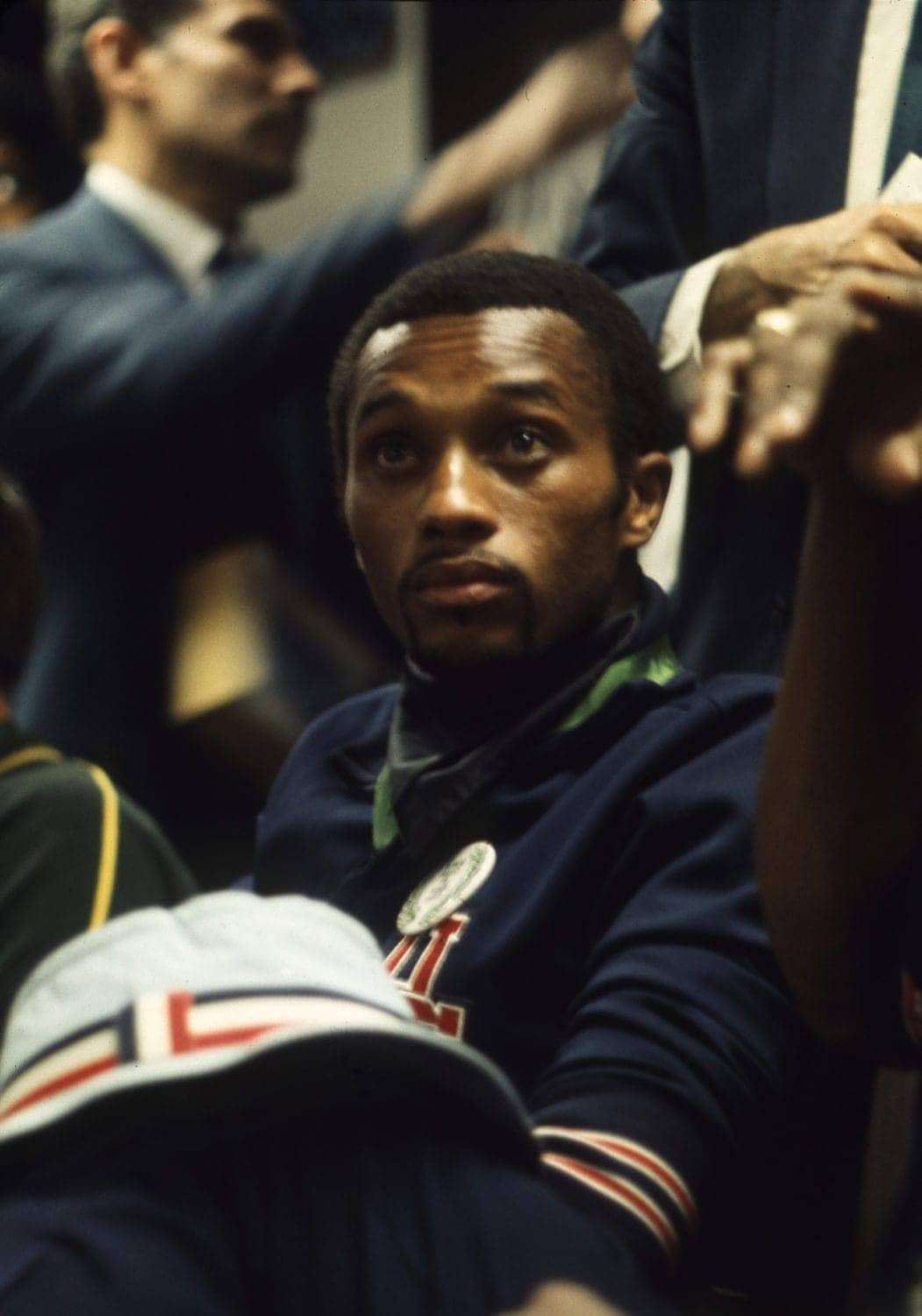

JR Valrey: What was the atmosphere like before John Carlos and Tommy Smith raised their Black Power fist at the Olympics? What was the energy like after?

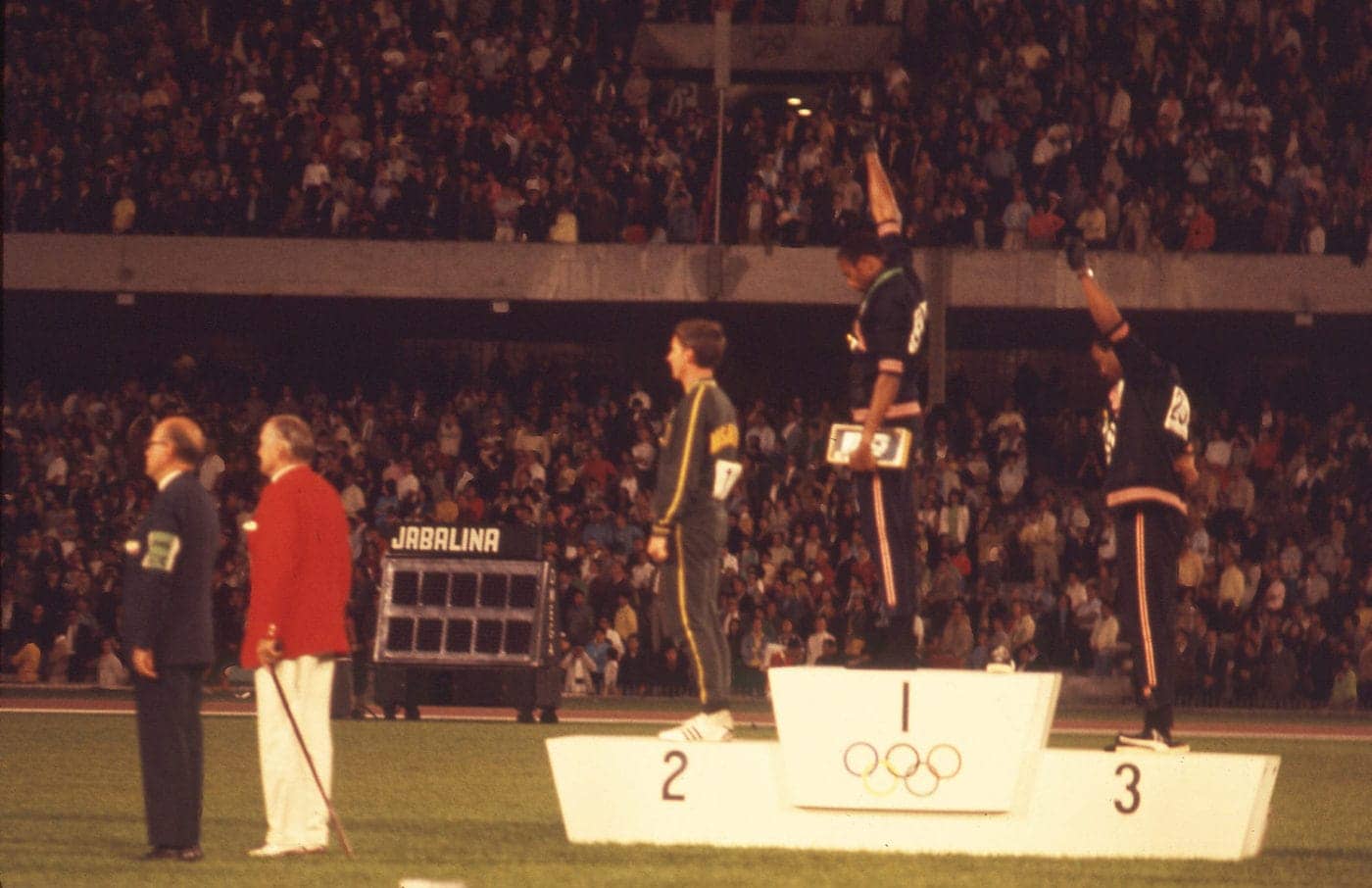

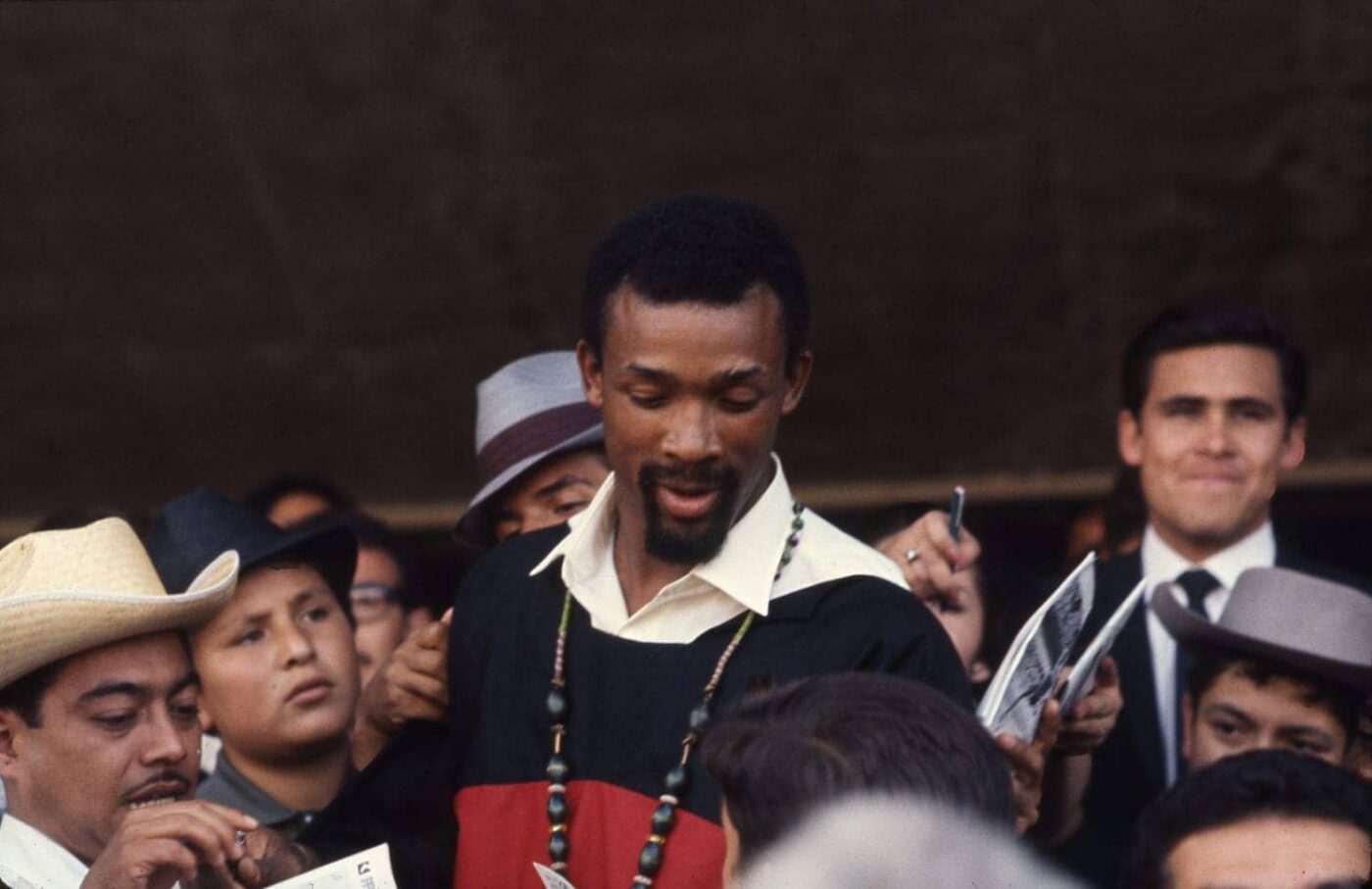

Jeffrey Blankfort: Mexico City, then one of the world’s largest, with a population of over 8 million, was like a ghost town when I arrived. No one was on the streets and reportedly, anyone seen writing anti-government graffiti on a wall was being shot. By the time of the games, when Smith and Carlos raised their black gloved fists, I suspect that an overwhelming majority of the Mexican fans saw the Black American runners as representing them as well.

What happened the following day seemed to prove that, when Carlos, who, like Smith, had been kicked off the U.S. team, returned to the stadium as a spectator and was instantly recognized. The fans around him began shouting his last name and soon the entire stadium joined in. It was loud enough to bring the events on the field and on the track to a halt. I don’t know about the Mexican press but, as far as I know, that amazing moment was never mentioned in the U.S. media.

It’s difficult, more than a half century later, to compare the energy in the stadium before and after Smith’s and Carlos’s fist raising because before and after that, the crowd had rewarded other fine performances on the field with the anticipated and earned applause, though not nearly with the same enthusiasm and sound level. And when Lee Evans, wearing one black sock in solidarity with Smith and Carlos set a world record by running the 400 meters in 44.8 seconds, the exuberance and applause of the crowd would have been tremendous regardless of the circumstances.

JR Valrey: What was happening in the U.S. at this time in the Black community?

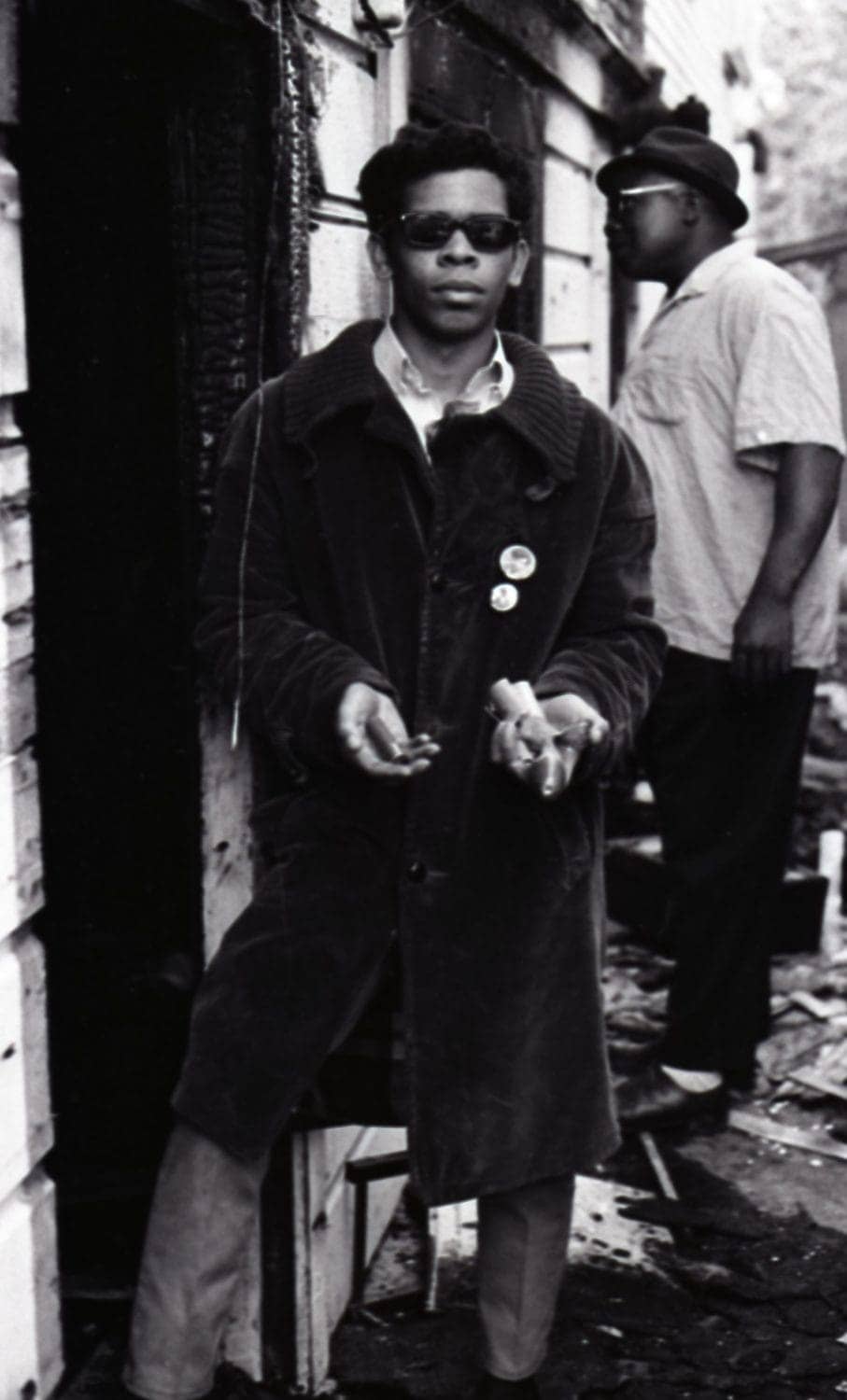

Jeffrey Blankfort: The U.S. was, like much of the world back in 1968, in a state of unrest. Protests against the U.S. war on Vietnam were occurring everywhere. The assassinations of Dr. King and Robert Kennedy had rocked the country, and the expansion of the Panthers from coast to coast, frightening the FBI as did their connections with other radical elements in the Black community, such as the Southern based Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, better known by its acronym, SNCC.

Hooking up in Oakland and appearing as speakers at the huge birthday party for Huey P Newton at Oakland’s Kaiser Center, two of its leaders, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) and H. Rap Brown (Jamil Abdullah al-Amin), briefly joined forces with the Panthers, only to have their alliance soon aborted by the FBI’s COINTELPRO, which went into overdrive.

In the athletic world and leading up to Smith’s and Carlos’s dramatic fist raising was the formation by amateur Black athletes of OPHR, the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Its goal was to organize an African American boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games and its chief proponent was Harry Edwards, the track and field coach at San Jose State, where Smith and Carlos were students. It is impossible to say today what might have happened had there been such a boycott, but nothing can diminish the impact and image of the world seeing those two raised black gloved fists.

JR Valrey: Did you get a chance to talk to Tommy Smith and John Carlos that day? If so, what were they talking about?

Jeffrey Blankfort: During the games, national teams were kept pretty much isolated from the public, and I don’t recall whether I first spoke with Smith before or after the press conference inside the U.S. dressing room following their protest. But I did manage to have a conversation through a fence outside the Olympic training track with Carlos, which was interrupted by the appearance of what was obviously an undercover government agent.

Sharply dressed and wearing no lapel ID, which was required of all visitors and media in that area, he approached us and addressed me in English and asked how I was enjoying Mexico. “Very much,” I replied. “It has the most beautiful women and the world’s best beer.” “Very good, Señor,” he said with a broad smile, then turned around and walked off. His message had been delivered. I was being watched. He had been the first Mexican I met since I arrived who hadn’t addressed me first in Spanish.

I did get to talk with both Smith and Carlos afterwards but not at great length as things seemed to be moving very quickly. And that, too, was interrupted. As I was driving them and their wives to the airport, my rented car had a flat tire and as they were in a hurry to catch their flight, I hailed them a cab while I remained behind to change the tire.

JR Valrey: When you got back, how did Ramparts Magazine editors respond to what you had captured with your camera? Why do you think Ramparts stole your photos?

Jeffrey Blankfort: I had sent my photos of the event to Ramparts by mail through the Olympic post office, and since I had arranged to do some other things in Mexico, it was more than a month before I returned to San Francisco. By that time, after publishing my best photo of Smith and Carlos with their fists raised, they had already sent the color slide to a photo agency in England, without my permission, and I never was able to get it back. Of course, they were glad to get my photo but not glad enough to send me a payment, and eventually I had to contact the publisher of the magazine, who was outside of the editorial loop, to send me the ticket for a flight back to the city.

What I mainly had to do after the Olympics was to take photographs of the Acapulco Film Festival for the Los Angeles Times for which I would have to get there on my own from Mexico City, and not be paid, but would be put up at a fancy beach hotel, with all my meals paid for, have an invitation to all of the festival’s parties, and have a taxi and driver for my personal use while, not having been paid by Ramparts, being close to totally broke. Bank credit cards, such as MasterCard and Visa, whose use today is widespread, were then only a few years old and not yet common.

What gained me the respect of my taxi driver and his fellow cab drivers was that I wore a blue JC Penney’s work shirt under my blue blazer to all the festival events. He immediately recognized it for what it was when we met and he and his buddies thought it was very funny. We became fast friends as much as the differences in our positions would allow and he took me around the city where the gaps between the rich and poor were wider than in any city I had ever been in. So, in Acapulco, at least in those days, the relatively well paid taxi drivers shared their wealth with their poor countrymen and women beyond their immediate families.

As for Penney’s work shirts, the company stopped making and selling them years ago.

JR Valrey: How did the readers of the magazine respond to your photos?

Jeffrey Blankfort: My photos were apparently popular with the magazine’s readers and some, like one head shot of Kathleen Cleaver with her amazing natural, were copied and, I learned, appeared in the windows of Black hair stylists not just in the Bay Area but across the country.

JR Valrey: How could people see your photographs online?

Jeffrey Blankfort: At the moment they can only be viewed on a computer at www.jeff blankfort.com, where there is a special section for the Panthers and another for the protests by Tommy Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics.

JR Valrey, journalist, author, filmmaker and founder of Black New World Media, heads the SF Bay View’s Oakland Bureau and is founder of his latest project, the Ministry of Information Podcast. He can be reached at blockreportradio@gmail.com and on Instagram.