by Bruce Richard

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party, former BPP member Bruce Richard recalled his experience in the Los Angeles chapter which culminated in a shootout. This October, Black Panther History Month 2023, is the right time to revisit that revolutionary history. The writer has since spent nearly his entire life as an organizer in the labor movement. He recently retired as an executive vice president of 1199 SElU, a 400,000-member healthcare workers union based in New York and is the author of the book “The Other New York.”

An enduring image in many of the retrospective observations of the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party is of the siege of the Panther headquarters in Los Angeles, where police forces attacked the office in the middle of the night, and the Panthers inside the building fought them to a standstill. What follows is a collective remembrance by several participants and observers.

Since almost nobody under 60 years of age today will remember that night, it is important to understand the context. In the 1950s, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover launched his COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) with the aim of disrupting and destroying the Communist Party USA. But with the rise of the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement of the 1960s, COINTELPRO expanded its mission.

A March 1968 memo stated the program’s goal was to “prevent the coalition of militant Black nationalist groups”; “to pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them before they exercise their potential for violence [against authorities]”; to “prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining RESPECTABILITY, by discrediting them to … both the responsible community and to liberals who have vestiges of sympathy. And to “prevent the long-range GROWTH of militant black organizations, especially among youth.”

In fact, the FBI’s primary operations in that decade were aimed not at fighting crime but fighting movements (and their leaders) who challenged the existing order. Dr. Martin Luther King was a foremost target of COINTELPRO. Such efforts on the part of the FBI dramatically move against the nation’s humane interest to create the atmosphere of caring and love that was so desperately needed.

Hoover soon began to criminalize the Black Panther Party, declaring it to be the number one threat to the country’s internal security. BPP members in a dozen cities were assassinated by law enforcement agencies. Lives were lost on both sides of a conflict and some were saved by the efforts of the people.

The Dec. 8 shootout in Los Angeles was one piece of this scenario, taking place one year after the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King. What led up to it – and its aftermath – illustrates the maturation of social forces, the building of ties between the BPP and the neighborhoods in which they lived and worked, and the crucial building of coalitions across communities and organizations. For me, this – more than just courageous individuals taking a stand – is my most lasting memory.

In the 1960s, life expectancy was at crisis levels in many Black communities across America. Deep pockets of poverty, resulting in catastrophic levels of chronic illness, infant mortality and hunger produced off-the-chart numbers of premature and preventable deaths. Unemployment for African-Americans hovered well over 40 percent in some communities, and on average was triple what it was for whites. This was regarded at the time as normal and raised few eyebrows. Black activists of this period are among the last generation to actually have the opportunity to speak with and physically embrace the former slave.

This was the social-economic context which gave rise to the Black Panther Party. In 1967, a year after its founding, the general public became aware of the BPP when a group of Panthers took firearms into the California State Capitol building, exercising the right to bear arms while dramatizing a response to racism.

Law enforcement circles were obviously provoked by the openly gun-toting, selfdefense-against-racist-violence stance of the Panthers, and were not about to tolerate Black folks exercising the right to bear arms, even if it was legal.

In 1969, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) spent several months conducting surveillance, preparing to invade the Panther headquarters. Neighbors reported an LAPD rehearsal of the attack. Parents and families pleaded and begged their loved ones in the Panthers to reconsider the life-threatening decision to be associated with the BPP. In 1968-69, there were more law enforcement shootouts with Panthers in the Los Angeles area than anywhere else in the country.

In the wee hours of the night on Dec. 8, 1969, over 300 police finally launched an attack and blasted through the Panther headquarters front door, apparently hoping to achieve the same results achieved by Chicago cops who four days earlier murdered young Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in their sleep.

National television images showed Chicago police officers laughing at the scene of the killings.

For important segments of the Black community in Los Angeles, Dec. 8 was like the day you earned your GED or the day you finally rode a bike after having fallen off so often. For the LAPD, it became the day their racist nightmares about Black people came true.

The Panthers were not sleeping as the police came crashing through the front door firing their weapons. They found themselves being repelled, dragging away one another to safety.

Young Panthers inside the headquarters found cover behind sand-filled walls and under sandbagged bunkers as bullets rained down on them from all directions. Bernard Arafat, then 16-year-old Bernard Smith recalls: “l had been relieved from doing security on the roof by Gil and was awakened in the library just before all hell broke loose. Police explosives demolished walls and furniture, ripping portions of the ceiling off. The building was saturated with tear gas and thick smoke. Broken glass and fragments flew through the air, shattered plumbing pipes. Panthers moved about returning fire, and hurled explosives from the windows. Automatic weapons fire repelled the assault for hours.”

Harry Carey, a Black Student Alliance (BSA) activist at UCLA: “People on my campus were in tears over what had happened in Chicago to Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. It was like hitting the beachheads in our community, reminiscent of World War ll.

With all that fire coming at them, these young people would jump off the boat into the water and head for the beach, while so many would lose their lives from this strategy. You had to be young to do this. Older folks would more likely have said: “Close up this boat, I ain’t getting off this ship. “ It takes a youthful spirit to tolerate such bold action, and that’s what the Black movement was producing, and they couldn’t kill enough of us to stop the momentum.”

The LAPD came to understand that the people inside the Panther headquarters would not be easy to dislodge and kill, so a military tank was eventually summoned from the rear. It rolled into place, intending to end this scheme gone wrong as rapidly as possible.

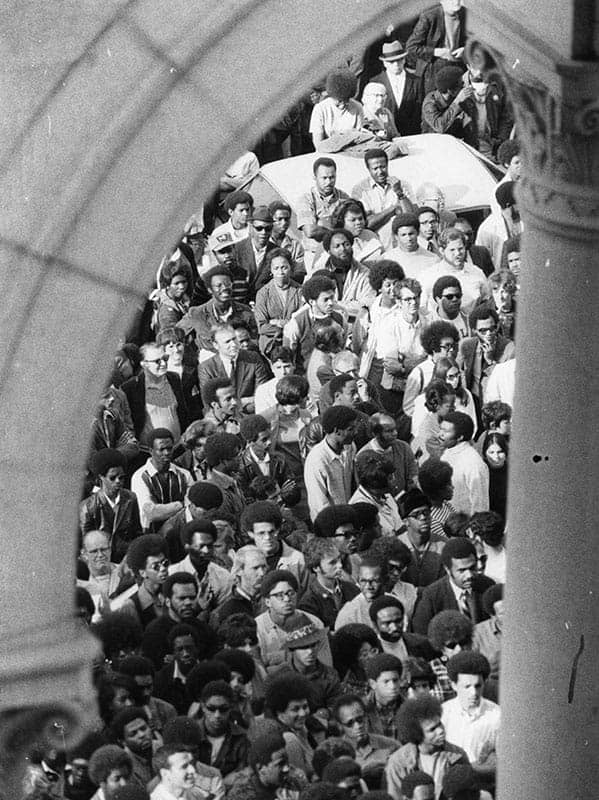

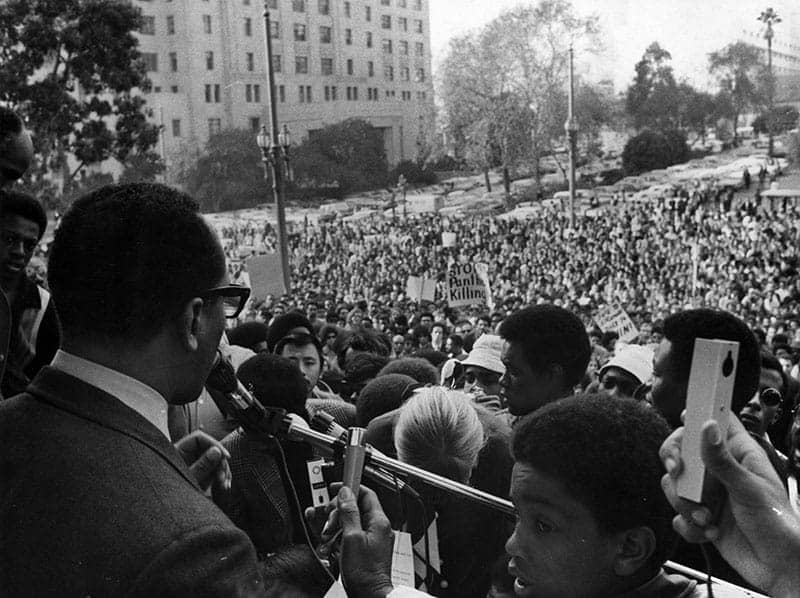

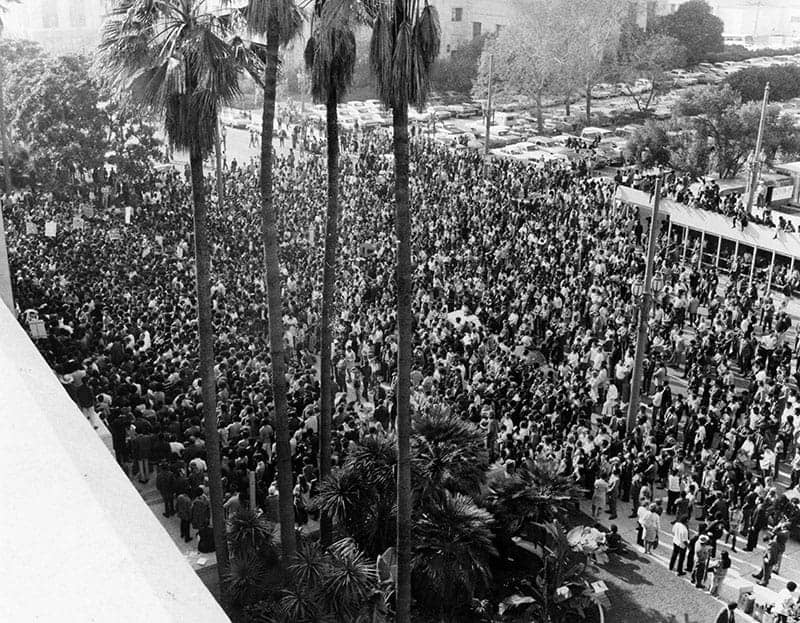

However the sun was coming up, and an enormous crowd from the community gathered waiting behind police barricades. As the assembly swelled into the thousands, the residents let it be known with no uncertainty that they would not passively accept this attempt to kill their youth. The crowd continued to grow in size and determination.

Mubarak Muhammad, then 16-year-old Panther member Tony Quisenberry, had worked at the headquarters the night before and saw what was unfolding on TV at his mother’s home: “l tried to get to the office, planning to somehow get in the back way and join them. The police had evacuated people from their homes for many blocks. I encountered barricades with thousands of people behind them, encouraging and cheering on the Panthers’ machine-gun fire from the building. It sent chills up my spine. State Sen. Mervyn Dymally, City Councilmember Gilbert Lindsey and Robert Farrell were calling for negotiations and getting hostile responses from the police.”

The pressure continued to build from the public’s boisterous presence. Soon thereafter, as new extraordinary images of Black folks working together materialized from inside as well as outside its barely standing remains of a building, a settlement was reached and a surrender was secured.

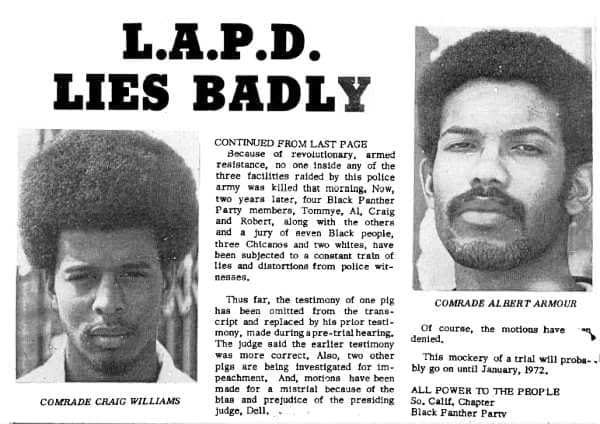

Though injuries were numerous, there were no fatalities. Thirteen people miraculously survived the assault. Two were young women emerging from the ruins clarifying the role of women’s work. All 13 were charged and jailed, but the LAPD was unsuccessful in duplicating the Chicago PD murders of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. Three days later saw the largest ever Black demonstration in the history of Los Angeles, where tens of thousands of young people rallied at City Hall in support of the Panthers.

Beverly Freeman, a member of the LA Teen program established after the 1965 Watts rebellion in response to the lack of social activities for poverty-stricken youth: “My Teen Post was so impressed by the Dec. 8 incident that we were encouraged to go and assist the Panthers with the aftermath of the shootout. I helped out and, because it was such an electric coming together of the community, a few of us joined the BPP.

“Eventually I married one of the shootout survivors, Roland Freeman. Young people are still always coming by, doing research for a paper, or to make a film or just asking questions. Roland passed in 2014, but young people still recognize the contribution and pay their respects. They see the Dec. 8 shootout as among the first times that L.A.’s Black people really took a stand.”

The Black Panther Party’s ideology and view on the right to self-defense resonated among the poorer strata and penetrated the social environment of jail and prison life.

Brother Kumasi, previously L.A. gang leader “Little Bird”: “l was a prison activist in Soledad State Prison in California during the Dec. 8 shootout. We listened to this incredible event live on the radio. We were truly inspired. It seemed like every 15 minutes the police in L.A. would ask the Panthers through a bullhorn to surrender. The inquiry was followed by machine gun fire coming from the building in response. This really fired us up, creating a frenzy-like atmosphere.

In the next several years, the noted prison activism of Panther leader George Jackson, Jonathan Jackson, UCLA professor Angela Davis and others led to massive prison reforms in California, allowing thousands of people to be released from prison. This period represented a breeding ground for the incarcerated who were breaking away from criminal activity and becoming socially aware like never before, becoming the best rehabilitation program ever. “

Ronald “Baba” Preston, then of the Black Student Alliance (BSA) at South West College in L.A.: “The civil rights and later Black movement opened doors through which a whole new generation of youth had access to college for the very first time. Following the Dec. 8 shootout, L.A’s Black Student Alliance (BSA) exploded into other counties and parts of the state and nation, becoming intricately connected. The BSA, one of the most radical organizations in a university setting, saw its role as bringing an advanced political and ideological perspective to the movement.”

The Dec. 8 shootout presents us with a snapshot of how the historically least active segments of the community became more socially conscious and how they were able to successfully intersect, coalesce and have an impact.

Following the 1965 Watts rebellion and prior to the Dec. 8 shootout, police had killed over a thousand (mainly Black) people nationally, hundreds of them in Los Angeles. In the months prior to the Dec. 8 shootout, Panthers prepared for an assault from law enforcement. No one knew when it might occur but all signs indicated it was inevitable. Beginning in the late summer, we worked to build a tunnel at the Central Avenue Panther headquarters. Panthers took shifts at night, rotating in groups of twos and threes, learning to wield the pick and shovel into the rock-filled earth and stuffing the dirt into sandbags.

Panthers employed the pick and shovel for Martin, for Malcolm, and a love for all oppressed people. The swing of the pick and lifting of soil was informed by the coffins of the four little girls of Birmingham and by Lady Day’s Black bodies that became strange fruit, plucked by crows as they were hanged from poplar trees. The many Black folks and even children being dragged away during the night, routinely lynched for exhibiting the mere perception of being equal, were memories not far from our minds.

The first night, young hands and bodies worked hard to break into the ground, overcoming numerous boulder-size rocks. We developed blisters, scrapes and cuts, as cruddy sweat gathered in the crevices of our skin. In one night, we dug a hole that was well over our heads.

The hole became a tunnel and symbolized how obstacles can be transformed. Wood was cut to insulate the tunnel. We eventually had 10-hour shifts, setting up 4”-by- 4” wood beams for the side and the top, and installing medal bracings to support the wall.

We poured dirt into the building walls and into sand bags that we placed along the walls, creating a fortified bunker. We cut a hole on the second floor giving easier access to the first floor. The “we” in this effort were numerous folks. Panthers were armed and security was tight. We rotated each night, month after month. Anyone falling asleep on security faced severe discipline.

Shirley Posey, then Shirley Hewitt, a Panther and the first in her family to attend college, married to BPP Minister of Education Masai Hewitt: “Before the December shootout, relations with the LA police were quite intense. Masai was self-educated, well known in L.A. and really a man before his time. He spent significant energy building solidarity with various parts of the Black, White and Latino communities, with unions, college students, progressive Hollywood producers and actors, anti-war groups etc. These ties and relations were vital.”

The atmosphere throughout the city of Los Angeles seemed to be informed by the Watts rebellion four years prior. Dialogue was fostered throughout the Black community; folks made commitments to one another as to what they were prepared to accept and not tolerate in their lives. Many residents got a glimpse of how improving relations with each other was crucial to more positive things happening in our lives.

The Watts rebellion was a statement that Black folks were fed up with racism and the routine murder and brutality of Black people by law enforcement. During the five days of rebellion, National Guardsmen and police killed 34 people. Corporate interests also made a killing, adding to the jail and prison industry as thousands were incarcerated.

Earlier, The Magnificent Montague, L.A.’s beloved R&B DJ on KGFJ-AM, had promoted the lift-yourself-up theme of “Burn Baby Burn” to describe how young people should work hard to overcome poverty. Watts’s residents gave it new meaning – a theme of rebellion – as white businesses went up in flames.

During the five-day rebellion, assorted police agencies patrolled with armed helicopters with spotlights as bright as the sun. Watts resembled in many ways an outpost of the Vietnam War, as it became the testing grounds for the militarization of local police. Helicopter patrols became a permanent fixture of the community. And Los Angeles became the birthplace of the elite paramilitary operation now known as SWAT.

Meanwhile cultural artists grounded in uplifting the Black community moved into the trenches nationally, parachuting in singers, musicians, poets, photographers and painters onto the front lines. There were writers, filmmakers and professional athletes as well. These multiracial, multicultural courageous women and men advancing social justice were part of the ammunition used to fight racism, oppose the Vietnam war and defend the rights of women.

Contributions from various sectors of the social justice movement had a unifying impact particularly on young Black people in Los Angeles, triggering all gang warfare to come to a complete halt, as gangs thoroughly disbanded. This was replicated in several cities across the country and was tremendously monumental.

Los Angeles community residents saw firsthand tangible evidence of social transformation in their neighborhoods. Residents felt a sense of personal ownership inspiring those around them. Numerous programs, introduced to address community concerns, also added jobs. Many of yesterday’s gang members and formerly incarcerated became social change activists.

By the late 1960s, residents seemed to regain an ancestral sense of responsibility. Perhaps it was a survival gene, passed down through generations to encourage Black folks to safeguard the collective effort to evolve and prosper. Folks began to reveal more of themselves, risking being further engaged with one another. They were able to overcome an apathy concerning their neighbors, which disguised the love and compassion in their hearts.

The people once invisible made themselves evident. Even in Leo’s pool hall in the same block as the Panther headquarters, you could hear affectionate dialogue amplified that included the words “brother” and “sister” and less negativity.

The so-called winos and drug-addicted considered themselves guardians of this new upsurge of social awareness. Still comforting themselves with artifacts left over from the rebellion, they set on rickety wooden crates and discarded furniture in the parking lot adjacent to BPP headquarters. They told their stories, shared their agony and humor, rediscovering experiences from a distant past that could be helpful to the moment at hand. They attempted to conceal difficult scars, but their smiles revealed the rotten teeth and poor health.

Panther Captain “Long John” Washington: “Al was one of these guys. I met Al in the 50s as a young kid hustling bottles, and Al was stable, doing great, working hard and making money. My family didn’t have much money, so Al used to buy the food and my mother would cook for him. It was a cooperative effort, mother’s cooking and Al buying the food, and that’s how my family would eat.”

Small businesses seemed to pivot, giving more consideration to patrons with little income. This created a different, more caring rhythm in the foot traffic carting the objects of their lives to and from the storefronts, up and down Central Avenue.

Some gay and transgender residents, historically further in the shadows, invisible to the invisible, began to discover a new sense of relevance, becoming the eyes and ears of this seemingly permanent breeze gusting through the neighborhood.

L.A. Panthers were mostly young and working class. I was part of a first wave of young people getting out of prison who, while locked up, made a collective decision to join the L.A. Panthers; Toure, Kibo, Lemuel, Chip, Chris and I were all previously considered unfit in the normal youth rehabilitation population of the state system. We had been sent to a prison called Tracy, which was the only prison retaining the Youth Act and that had beds in an adult population for the so-called incorrigible youth.

We previous representatives of the community’s worst, who sidestepped the gutter, were resuscitated by the potent fumes of the movement. We would reflect on how we owed a significant portion of our personal growth to the socially conscious counselors during our numerous visits to L.A. County Juvenile Hall. These counselors helped us to see each other and our surroundings much more positively. They were the kind of dedicated public servants that should be a bottom line standard for the juvenile system.

Under the radar in 1969 Los Angeles were social forces in motion, organizations and associations and committees with distinct ideologies, coming at social justice from various vantage points. Taking, often unknowingly, parallel pathways, they stood against injustice using non-violence or violence, being for “integration” or “separation.” It didn’t matter: To be against injustice was to expose yourself to harassment, jail and even death.

The strategic debates were important to maintaining direction under an umbrella group of organizations called The Black Congress. However, its later demise came because many organizations, caught up in personalities, placed more value on their differences than on their common ground issues. Many sought to bring about change against an external force, not adequately recognizing how social change is also a transformation inside ourselves, overcoming the enemy’s view of us, embedded inside our characters, as a remnant of slavery.

The government took advantage of internal dynamics in the Black community, pitting organizations against each other. However, what is most important is that significant elements of the social justice movement exhibited an insufficient appreciation to working in alliance or coalition. The movement had not achieved the necessary social maturity. Fortunately the potent trend of unity sweeping across the country could frequently snuff out such shortcomings.

Bunchy Carter, was a young prominent figure among L.A.’s Black youth – a former leader of the largest L.A. gang, and a poet extraordinaire. Bunchy transformed himself, an example of how various forces, including the civil rights movement, were in motion prior to the Black Panther Party, all navigating deeply into the social fabric of society to rescue and activate.

Sherwin Forte, one of the six original Panthers: “l first met Bunchy in the Bay Area. The successful recruitment of brothers and sisters like Bunchy increased an important dimension that was needed in our movement. Bunchy was carefully chosen to head up the Southern California Chapter.”

Bunchy and Panther John Huggins were murdered in January 1969 by members of the “US Organization,” a group with a nationalist perspective on Black liberation. It was headed up by Ron Karenga. These killings were associated with the government’s strategy of divide and conquer, leaving the social justice movement in L.A. in shock, more fragile and vulnerable.

Law enforcement took full advantage, seizing the opportunity to discredit the movement. But Bunchy’s wife, Evon, and John’s wife, Erica, were also Panther activists. Surviving this horrifying tragedy, they and the other L.A. Panthers felt obligated not to sustain the backward legacy of Black folks bringing injury to one another.

Harry Carry: “The killing of Bunchy and John was extremely demoralizing to the entire L.A. movement. But a group of young brothers got out of prison and really helped to energize us. These brothers had a sense of the community, had firm ties to the people, and brought rich new blood and passion.”

Bunchy and John’s murders came soon after another police shootout, killing Little Tommy, Robert and Steve, three young L.A. Panthers. Panther Harold Taylor: “l had just joined the Panthers and the death of the three brothers, killed by police in an L.A. gas station, was quite shocking beyond anything I can express, particularly when you factor in the murder of Dr. King two months earlier. However, these realities helped us accept, in a real way, that the cost of our activism could very well mean death. “

Panthers formed columns and marched for hours through the streets in the darkness. Panther Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald, then 19 years old: “Joined by significant numbers of young residents, we poured our hearts and souls into our bodily expressions of love for the people, chanting and singing songs of liberation from all over the world. Residents loved the R&B Temptations marching steps. You could occasionally hear a toddler’s voice murmur ‘Power to the People.’ Such nightly actions bolstered enthusiasm, helping people to become connected.”

Mubarak Muhammad: “We were revolutionaries in a war, intentionally using the cover of darkness, marching proudly and chanting, ‘Piggy Wiggy, you got to go now, bang bang, dead pig.’ We were under a lot of scrutiny from the police, always with their zoom lens cameras taking pictures, regularly being pulled over by the police during the day. But marching like soldiers at night, we had authority, and got a powerful response from the people.”

Distributing the Panther newspaper and talking with residents was a daily activity. Chip Fitzgerald: “We engaged in political education among ourselves and then would go knock on doors. Residents welcomed us into their homes. At their front doors and in their living rooms, we learned more when we explained the key articles in the weekly Panther publication. We encountered very intelligent residents, many with a more developed sense of the world than we had. Some residents were quite conscious and deliberately used this forum to inform and educate us.”

Baba Preston: “In 1969, we saw the Black Student Alliance as an umbrella group and a bridge for all Black Student Unions. Most student organizations were a part of this hub. And many Panthers participated – Bunchy Carter, John Huggins, Albert Amour, Little Joe, Wayne Pharr, Geronimo, Joan Ringo, Sister Tommy Williams and others. A lot of us got politicized in the mid-60s by the United Front, which influenced Black radical politics among the youth. This is where Masai Hewitt, a gang member known as “Bright Eyes,” sharpened his awareness, and eventually became BPP minister of education.

A brother, Dedan, was also in the United Front and became a leader in Youth Authority prison. Dedan was an important influence in getting prisoners to see college as an avenue to advance Black progressive politics. After his release from prison, Dedan was prominent in the Black Student Alliance and played a significant role in the cross fertilization with the Panthers and others.”

When I met Panther sister Tommye Williams, a Dec. 8 shootout survivor, she was very dedicated to the tutorial program at UCLA which went into depressed neighborhoods of the city. Tommye and others were concerned about effects on children from racism in the educational system. The university program rented houses in the community and recruited local children to participate in a wonderful learning experience. The program hoped to jump start an appetite for education and activism. At least one tutorial program became an emergent Panther-operated liberation school.

Panther Arthur “Tha” League, recently from Tennessee, cousin to Pulitzer prize winning journalist, diplomat and civil rights activist, Cart T. Rowan: “l really looked forward to the Masai Hewitt Cadre classes, because I learned so much. I saw the unity between white college students and the Panthers really develop, especially when I experienced white students leading confrontations with the racist John Birch Society in Orange County. This showed me that very powerful things were possible. I experienced good things between the Black and Chicano community. Panthers assisted the Brown Berets in starting their first free breakfast program in L.A. Coming from the very segregated South, these experiences really moved and educated me.”

The community very much appreciated the BPP for its Free Breakfast Program. Mubarak Muhammad: “The Free Breakfast Program was significant because we were cooking breakfast for those kids that didn’t have much food. They were like me and my family, and now I was bringing grits and biscuits to those kids to eat. It was truly a survival program. This felt so very rewarding and created a deep and thankful feeling about my role.”

Arthur was arrested at the home of actor Donald Sutherland in July 1969. Having always maintained his innocence, Arthur remains the only Panther in Southern California ever convicted of taking the life of a police officer.

Panther Luxey Irvin, 19 years old at the time: “l was quite inspired by the breakfast program, doing it because it addressed the real problem of hungry children. I remember the local grocery stores, small businesses and the International Longshore and

Warehouse Union (ILWU) contributing to the breakfast program. It was inspiring to know that others were working with us to confront this issue.”

Lux’s father ran a beauty salon and barber shop in Watts. He was also the childhood friend and barber of City Council representative Tom Bradley, who in the 1970s became the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city. Lux’s mom, Mrs. Irvin, was a devoted nurse much appreciated by the children and youth at L.A. County’s Juvenile Hall. Two months before the Dec. 8 siege, Lux was shot and arrested along with Panther Robert Williams after a shootout that left a police officer paralyzed.

Chip Fitzgerald: “It was insightful to see those hungry little mouths putting away the breakfast, undistracted end leaving with smiles of gratitude and appreciation. It served a dual purpose of being able to serve the community, and also embedding ourselves in a way that would later assist us. It allowed the community to be more enthusiastic about their surroundings, seeing a different and better side of themselves.”

One morning, a few months before the Dec. 8 shootout, mothers and children waited outside a Free Breakfast Program location that did not open on time. Chip had the keys and normally opened up every morning. Chip would never show up again, and is now the longest confined Panther political prisoner, his conviction stemming from the shooting of a highway patrolman and the death of a security guard. Chip miraculously survived a gunshot wound to the head.

[PrisonRadio.org writes that on March 28, 2021, Chip suffered a massive stroke and passed away in a California hospital while lying in shackles. “Chip was the longest held ex-Black Panther in America. Romaine Chip Fitzgerald, after over a half century in chains, returns to his ancestors.” – ed.]

Black folks are constantly asked to forgive, to put the racial injustice of that period behind us. But there is no corresponding apology or forgiveness from the establishment, even toward those whose legitimate mistakes had nothing to do with personal profit or gain and were on behalf of the anti-racist movement during the 1960s.

JD, a young child of the breakfast program in 1969: “l was 9 years old and, as a kid back then with big time conflict in my family, not enough food and dependent on the breakfast program. We all really liked Chip. He schooled us about a lot of things and made me feel so much better about life. I was more disturbed over not seeing and hearing his supportive voice that morning than I was with missing breakfast.”

L.A. Panther leader Elaine Brown (later national BPP chairperson): “The breakfast program was vital to the healing process, overcoming the painful episodes of half a dozen Panther deaths over the previous year. Panther Joan Kelly and I were so proud to have secured our first space for the breakfast program, which also depended on contributions from local businesses. We used the community’s existing economic resources to collectively feed hungry children.

“Elder Lorenzo Paytee, a Seventh Day Adventist minister, offered his church to operate our first free breakfast program. The only thing was that no meat and only veggie meat alternatives were allowed. We had to spice it up. But we were so appreciative, as this program had a serious motivating impact on how we saw our role and how the community saw us.”

Elder Paytee was loved and regarded highly in a mega way by the thousands of church members all over the region who approved of his various community campaigns. Coincidentally, he was also the principal of my elementary school. My parent grandmother, a very dedicated Seventh Day Adventist, domestic worker and former sharecropper from Magnolia, Miss., had gotten me into the third grade at the L.A. Union Academy, a Seventh Day Adventist school. Elder Paytee conducted thoughtful mentoring and paddling, both acceptable options to improve performance. However I was permanently kicked out of school toward the end of the sixth grade.

Elder Paytee: “l believed in the breakfast program and I recall having great conversations with Panthers, and I respected a few of the leaders like Geronimo, even though I did not agree with many things.”

In 1969, I was 18 years old. As fate would have it, Elder Paytee came back into my life.

On the night of Oct. 18, Elder Paytee was contacted to transport me to UCLA Medical Center. I had been shot multiple times by police officers and would not survive without emergency medical treatment. I was barely conscious as Elder Paytee looked into my eyes, insisting I stay alert. He said that it was a miracle from my grandmother’s prayers that placed him there.

So, less than two months before the Dec. 8 shootout, I was hospitalized and arrested for a tragic shootout in which two police officers were wounded, and the dedicated Panther, Walter “Toure” Pope, was killed. I was devastated in every way by this event. Toure’s death added yet another agonizing misfortune that L.A. Panthers and the community had to sadly adjust to, one of numerous incidents that added to the combustion leading to Dec. 8.

Fortunately for the 13 Panthers who survived the shootout, the power of the people prevailed. Important segments of the community could now imagine themselves, in interrelations with others, able to create a more just society; to improve economic survival, expand community health and education and reverse mass incarceration. The massive intervention of the community – thousands of neighbors right there on the spot – did not just save lives. It altered them.

Our challenge now is to take these lessons and produce a deeper appreciation for the necessity of working in concert, overcoming division and cynicism, encouraging our communities to become the creators of their tomorrow and their own most powerful weapon to achieve social progress.

The relations that community segments have with each other have always been more crucial than the community’s relationship with the government power structure. In Los Angeles in 1969, college students, cultural workers, small business folk, clergy and union members discovered each other as their first line of defense. Dedicated elected officials, Juvenile Hall counselors, former gang leaders – incarcerated and formerly incarcerated – and even my grandmother’s prayers, all came to recognize the enormous life-saving achievements we can only accomplish together.

Author Bruce Richard can be reached at BruceR@1199.org.