by Cecil Brown

Today is Feb. 1, 2024. Exactly 64 years ago to the day, on Feb 1, 1960, four students from A&T College sat down at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., and thus desegregated the racist Southern system. This event was the first blow against this racial segregation system which had been erected to slow the progress of the slaves freed from the Civil War.

The revolution, which started when four students – four Black college freshmen, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. and David Richmond – sat down at Woolworth’s diner and asked for a cup of coffee. They were refused, but they came back the next day with 20 more students; again, they were refused. They came back the third day, with 300 students. By the end of the week, 1,500 students, including students from Bennett College for Women, swarmed the diner.

“As demonstrations spread to 13 states, the focus of the sit-ins expanded, with students not only protesting segregated lunch counters but also segregated hotels, beaches and libraries,” according to History.com.

It took months, but finally, on July 25, 1960, the Greensboro Woolworth lunch counter was integrated. Counters in other cities did the same in subsequent months. In addition to desegregating dining establishments, the sit-ins led to the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Raleigh. Activist Ella Baker, then director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, organized the youth-centered group’s first meeting.

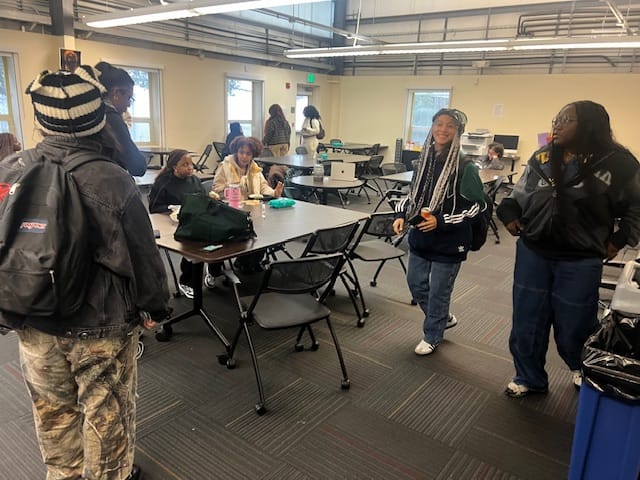

But today, in 2024, 64 years since those four young men walked into Woolworth, what has it changed for young Blacks? What is it like for students at UC Berkeley today? I decided to visit the Fannie Lou Hamer Black Resource Center at UC Berkeley. As I walked there, I noticed that it is tucked so far away in the back of the campus that it was hard to find.

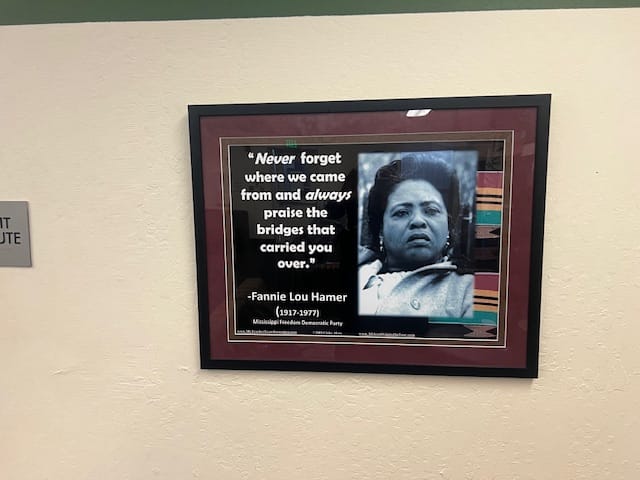

Who was Fannie Lou Hamer, anyway? If it had not been for the Greensboro sit-in, she may not have become the great leader she became. She was a civil rights leader. Hamer was born Fannie Lou Townsend on Oct. 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi. She was the last of the 20 children of Lou Ella and James Lee Townsend.

According to her bio online, she “was extorted, threatened, harassed, shot at and assaulted by racists, including members of the police, while trying to register for and exercise her right to vote. She later helped and encouraged thousands of African-Americans in Mississippi to become registered voters and helped hundreds of disenfranchised people in her area through her work in programs like the Freedom Farm Cooperative.”

Most famous for representing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, they replaced the all-white delegation sent by the official Democratic Party. Hamer’s delegation sat down, and the whites walked out, ending legal segregation in US politics. Hamer also organized Mississippi Freedom Summer along with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The black panther used as a symbol of Freedom Summer was picked up in Oakland by the organizers of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

My first question to the UC Black students would be, “Do you know who Fannie Lou Hamer is?”

She was a sharecropper at 44 years of age when she heard about the students’ sit-in. She became an inspiration to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

I was 17 or 18 years old and had recently matriculated into A&T College, where I roomed in Scott Hall with David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell A. Blair Jr. and Joseph McNeil, the Greensboro Four. That’s where we played bid whist and chess into the wee hours of the night.

The student-led desegregation movement that led to the Civil Rights Movement was conceived of in our bull sessions. We were the sons of sharecroppers and the grandsons of slaves. But unlike our forbearers, we had the opportunity for an education, and we had time to catch our breath and to think of our next move.

In those sessions, we discussed the Black writers we read in class and all of the topics we heard outside the class in the streets. Nothing was off the table. Somebody had seen a film about Gandhi, and the idea of nonviolence was batted around quite a bit before a young freshman who didn’t know any better took up the idea and marched down that drizzly Monday afternoon and tried it out on the Woolworth diner.

The rest of us sucked up the humiliation that we experienced when we left the security of the university and went to class. We were not as brave as the Greensboro Four, and it was not until we came in from dinner back to the dorms that we heard what they had done; they were screaming out with absolute joy: “We beat Woolworth! We beat ‘em!”

No one knew what in the hell they were talking about. Then they explained they had gone down to Woolworth. They had purchased some items and had kept the receipts. Then they sat down on the stools where the sign said, “Whites Only,” forbidding them to sit.

When he sat down on the stool, David Richmond said he felt like a man for the first time in his life. For the rest of us, who thought we were already men, this was quite a boast.

We all thought we were men even though we were still only 17 or 18 years old and yet when he said he felt like a man for the first time, we all knew that he had had an experience which we had yet to have. Instinctively and unconsciously, we understood that something had really happened to him.

A policeman showed up, but he didn’t know what to do with his baton, because the young men had not done anything to justify using it to crack their heads..

A little old white lady came up to them and put her hands on the shoulders of one of them and said, “I’m proud of you!”

These are the stories they told that afternoon and evening in Scott Hall.

Dr. Darwin Turner, our English teacher, had lectured us about rituals of manhood in Melville and Faulkner, and I knew a ritual when I saw one. I eagerly joined the picket line. I was not going to miss out on trying out this ritual for myself.

The first day only four men went down, but the second day there were 20, the third day there were 60 people and the fourth day there were 300. By the end of the week, they were a force of 1,500 plus 500 students gathered around the Woolworth on Market Street.

On the fourth day, a young woman was reading the newspaper about what happened at Greensboro, and she turned to one of her friends from the same college: “Do you think we could do this here?” Within a few days, they had desegregated the local Woolworth in Tampa, Florida..

It took five months and three weeks and three days before Woolworth in Greensboro declared that they were desegregating in 50 cities in 13 states throughout the South. Desegregation spread like wildfire throughout South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas. It was all done by students from Scott Hall.

I wonder as I walk into the door of the resource center if the African-American students at UC Berkeley know anything of the history of the African-American struggle to desegregate the South.

I spoke with several students about what it was like being at UC Berkeley in 2024. Did they feel like students felt in 1960 that they were discriminated against? Did they feel that affirmative action’s demise had left them isolated and limited? Were they like the four young men who walked into a diner and were allowed to purchase items but not to sit down and enjoy a meal with others who were more privileged?

But before I engaged them in the conversations I had with them, let it be explained that the Dixie desegregation of the South by African-American students led to another revolution, which has been called the Free Speech Movement.

During the summer of 1963 and 1964, whites from all over the country came down to the South to participate along with Black college students in the effort to register Blacks to vote. One of the most inspiring leaders of that Free Speech summer was Mario Savio.

At the end of his sojourn to the South, Mario Savio came back to Berkeley and inspired and starred in the Free Speech Movement. On Berkeley’s campus there is a Free Speech restaurant surrounded by images of Mario Savio and other members of the Free Speech Movement.

Across campus is another building dedicated to the Free Speech Movement and Mario Savio. It is centrally located on campus, but the resource center is ingloriously socked away near the police station. It has no access, no telephone, and is virtually hidden from the public..

In 2017, African-American students fought a long battle just to get the room which came to be called the Fannie Lou Hamer Black Resource Center.

In comparing the two buildings, one can say that in keeping with the Southern tradition of separate but unequal, the Mario Savio Café is lavish, a public representative of all that’s positive, but the Fannie Lou Hamer building is stuck off in a dark corner of the university.

When I first came to the university in 1970 to teach in the English Department, Black students were about 15 to 20% of the student population. Today the population of Afro-Americans is about 3%.

Through the passing of Proposition 209 (ending affirmative action), the number of Blacks has been whittled down to 2%. In 1970, when I was teaching my first class on African-American literature in Berkeley in Wheeler Hall, the class was overflowing with African-American students who were interested in Zora Hurston, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright.

In 1970, there were not a sizable percentage of Chinese or Indian students. Occasionally, there was a small group of Ethiopian students. Today after the attrition of African-American students to 2%, the number of Chinese and other Asian students has risen to a level some estimate as 40% of the student population.

One of the first students I met when I came in was Masoud Mcleod, sociology major, who comes from East Los Angeles. I asked him what he thinks of Fannie Lou Hamer?

He looked at me and said, “Fannie Lou who?”

I pointed to the picture on the wall.

“Her?”

He laughed. ”Oh, wasn’t she a civil rights leader?”

“She was a leader in SNCC,” I reminded him.

“I didn’t know that.”

“She was influenced by the Greensboro sit-in. Did you ever hear about that?”

“No, I never heard of them,” he said.

“What do you get out of coming here?”

“I like meeting my friends.”

I asked him a question about the lack of a critical mass of Black students. Did he ever take classes where he was the only Black person in the classroom?

“That’s just one thing I really don’t like.” He said, “I took a class on Black philosophy, but the teacher was white and I was one of only two people in the class who were Black!”

I explained to him that a few years ago when I first came to teach, there were a critical mass of Black students so you would have classes in which Blacks didn’t feel isolated as he did.

My mouth went dry, and I wanted a glass of water. I was directed to the small kitchen, where a young lady poured me a glass of water. As I drank the water, I engaged in a conversation with the young Black woman and as we talked, she revealed that she was from Nigeria.

She had never heard of the Greensboro Four nor Fannie Lou Hamer either. But what she liked so much about the center was that she was able to meet with her friends there. I congratulated her on her average American English accent and thanked her for the water.

I took a seat next to a young lady who was actually reading a book as opposed to staring at the screen of a laptop. She was an English major, and her name was Leila Mendiola, 19.

I asked her what was she reading in her English class. She said, Olaudah Aquiano, African abolitionist.

Had she ever heard of Fannie Lou Hamer?

“Wasn’t she a civil rights leader?” “Yes, she was.” In fact, that’s a picture right there. I pointed it out. “Oh yeah,” she remembered

Did she take her English classes from African-American professors or from white professors? “White professors,” she answered. She replied that although she had white teachers in the English Department, she had taken a class in the African-American Department with a Black teacher.

“And what did you read in that class?”

They read Octavia Butler’s “The Kindred.”

“It was great!” She exuded.

What was so great about this experience as opposed to her regular white English class?

“It was great because of the class discussions with other Black students,” she said.

In her English class, most of the students were white and she was one of two Black students in the class.

“What was so different about reading this book with an African American teacher?

“One of the main points of the book,” she answered, “was how powerful Black literature could be for Black enslaved people.”

Dana, the main character in the book, is an author herself, she explained, “but she had a career path to lead her to be literate, and when she went back in time in the 1800s, the slave owners were very scared of her because she was literate.

“For one thing, she can speak proper English like white people. She had a lot more freedom because of that. The book illustrated how powerful she was because she was literate. Because she was literate, that was very scary for the whites.”

I asked her, “What would Blacks get out of studying Black Literature?”

“I think that it would be very liberating,” she answered, “because our stories and our experience and what we go through can help you understand our lives, and we would understand better white supremacy, so I think it’ll be a very good thing for literature to be studied. I think that what the story is doing is spreading awareness about our reality.”

“Have you read Toni Morrison?”

“Yes, I really loved ‘Beloved.’”

I asked her why is it important more Blacks do not study Black literature and unfortunately most of the people who teach literature are not Black.

“I think we have the possibility to combine humanities with technology in a discipline called DH – digital humanities. This would encourage students to study both the literature of Black authors and the technology together.

She agreed.

I picked up one of the lists of new classes being taught in the American Cultures Center, and the first name I saw was Adam Hochschild.

When I first came to Berkeley in 1970, I was teaching in the English Department. I had a neighbor named Adam Hochschild. Adam, as it turned out, was writing a novel. He had just graduated from Harvard and with his wife and young son he lived right next door to me. Adam and I both began to work on novels. He began to write a novel about white life, and I began to write a novel about my life in North Carolina.

My book, “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger” (1970, Farrar, Strauss, Giroux) was published and in a few months I was a celebrity. English Department Professors Mark Shorer and Flanagan came to the house for parties; and Adam saw clearly what the subject matter of Black culture could do for a writer.

As the only Black member of the English Department, I took great pride in inviting seasoned Black faculty members such as Mark Shorer, the great literary critic, and his wife Ruth, Tom Flanagan, also a literary critic, and short story writer Lenny Michaels to my parties, where we danced to James Brown. It seemed it was not long after that that Adam abandoned his novel and turned his attention from trying to finish his white book to writing a book with a Black theme.

I learned a lot about Adam. He told me, for example, his family had become rich from South African gold mines. When he decided to turn his attention to Black history, he turned his attention to King Leopold. King Leopold was an appropriate metaphor because both the author and his subject had made fortunes from Blacks. When the book was published, Adam realized he had found his subject: Black history.

He continued to write books about Black life, although as a white person he had very little experience at it.

This list of courses offered by the American Cultures Center was developed after students demanded to have Black culture taught. A number of white immigrants, led by Victoria Robinson, an English woman, decided that other groups had to be recognized. Anybody who taught an American Cultures class had to include two other groups.

Each semester a list of such courses began to develop into classes taught by whites. At the top of the list was a class taught by Adam Hochschild.

This was an indication that in the English Department at UC Berkeley, most of the literature, even fiction, is taught by whites.

“Do you think Black writers do better at writing Black literature than white ones?”

“Yes, of course, because the Black writers can really see what our experience has been and what we have contributed to the world. You begin to see and identify with the life of Black people.”

“Not so much with white writers and Black literature?” I asked her. She smiled, “No, not so much.”

Leila’s story brings me back to the Greensboro Four. What is meaningful for Black people is the symbolic growth that comes from the rituals. We like to grow and mature from having our stories told by us to us.

When I taught Zora Neal Hurston to a critical mass of Black students back in the ‘70s, this experience is one in which the word was being passed down orally. Nowadays the only teachers who are hired to teach Zora Neal Hurston at Stanford and UC Berkeley are white.

As I was leaving, I spoke with a young man Marcus, who was from San Bernadino. He told me that his father comes from Samoa and he grew up listening to Simran hip-hop like the Boo-Yaa TRIBE. What did he think about the Fannie Lou Hamer Center? Again, he had not heard of her.

I pointed to her portrait on the wall only 20 yards away. Recognizing her, he smiled and said, “Oh yeah!”

Novelist and educator Cecil Brown, UC Berkeley professor and director of the George Moses Horton Project at the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) at Stanford University, is also known as the close friend, screenwriter and biographer of Richard Pryor and as the author of “The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger,” “Stagolee Shot Billy” and most recently “Pryor Lives: How Richard Pryor Became Richard Pryor: Kiss My Rich Happy Black Ass.” Brown can be reached at browncecil8@gmail.com.