by Howard Isaac Williams

On June 19, 1865, Union Gen. Gordon Granger and his army entered Galveston, Texas, and put President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation into effect, freeing the enslaved people of that state. On the previous June 2, also in Galveston, Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith had surrendered the last Confederate force still fighting in the Civil War (1861-1865), marking the end of a cataclysmic conflict that had cost at least 618,000 American lives, more than in any other American war.*

When the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in Galveston – 900 days after it was issued on New Years Day 1863 and 65 days after the assassination of its author – Black Texans responded to the liberation with jubilation. In the following years, this celebration was repeated throughout Texas and has come to be called “Juneteenth.” As it is today, the holiday would be celebrated with church services, historical reenactments, feasts, music and other recreation. Reflecting its Texas roots, Juneteenth celebrations include barbecues and rodeos.

Juneteenth eventually spread to Black communities all across America. In 1938, in the depths of Jim Crow, Texas became the first state to officially recognize Juneteenth when Gov. James Allred issued a proclamation recognizing the celebration. By 2020, 49 states had followed Texas with some form of official recognition and both presidential candidates had endorsed a national holiday. In 2021, President Biden signed the Congressional act making Juneteenth a national holiday commemorating and celebrating the end of legalized slavery in America.**

Although the original Juneteenth in 1865 marked the end of slavery in Texas and the Confederate states, it did not completely prohibit involuntary servitude in the United States. The Emancipation Proclamation did not affect states that had not seceded, and chattel slavery continued in Kentucky and Delaware until the ratification of the Constitution’s 13th Amendment prohibited the “peculiar institution” throughout America on Dec. 6, 1865. Abolition is truly something to celebrate; and although June 19, 1865, did not drive the final nail into the coffin of American slavery, there is a strong case for observing its end in the last Confederate state as the day to celebrate.

In addition to the abolition of slavery, do Americans have another reason to celebrate Juneteenth? One that is related to the original one and equally as valid?

Should we also celebrate Juneteenth for the end of the war that killed more Americans than any other conflict?

Just as Juneteenth was not technically the last day of legalized slavery in America, it was also not the last day of the conflict. Yet in relation to the day that the last Confederate forces surrendered and to the cause they fought for, Juneteenth is close enough to also be the day we celebrate the peace that came after such a costly war.

Today most American historians agree that slavery was the main cause of the war. Even people who believe that states’ rights was the most important cause acknowledge that slavery was a large factor in the states’ rights argument. After all, a state’s “right” that Confederates were fighting for was for the state to allow slavery.

When Gen. Granger entered Galveston to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation, he could have only done so because of the nearly apocalyptic achievements and sacrifices of hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers and sailors, Black and White. In the first two years of the war, the Union Army denied Black people the chance to fight. But as fantasies of an early victory evaporated in the searing heat of battle, Congress accepted the advice of Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass and on July 17, 1862, opened the Army to Black men – who responded in droves. By the war’s end, 179,000 Black Americans were Union soldiers, 10% of the force.

For all Americans, the end of slavery also meant the end of a horrific war caused by slavery. In addition to the hundreds of thousands of men dead, many thousands suffered amputations, cities were leveled and farms were burned across wide swaths of the American countryside.

Black troops suffered higher casualty rates than White soldiers on either side and when captured by Confederates were often summarily executed. Only when Lincoln threatened to do the same to Confederate prisoners did the war crime decline, although it never completely ended.

Once they were allowed to fight, Blacks fought in all theaters of the war. Even before the war began, Blacks had been serving in the US Navy, and by the end of the war, 19,000 Black sailors comprised 16% of the force. Many freedom loving Black men escaped slavery by rowing out to Union boats and ships and enlisting in the Navy or Army upon coming aboard. On some occasions, Naval officers lamented that there were more Blacks escaping slavery than their boats were able to hold!

Black sailors participated in the Navy’s blockade of Southern ports that crippled the Confederate economy and weakened its war effort. When the Confederates tried to blockade Washington, D.C., by sabotaging or seizing Potomac River ports above and below the nation’s capital, the Navy broke the blockade with the help of Black sailors on their gunboats and Black spies on the riverbanks. On the Lower Mississippi River, Black Southerners and the Navy used similar tactics to help win the critical Vicksburg campaign that split the Confederacy.

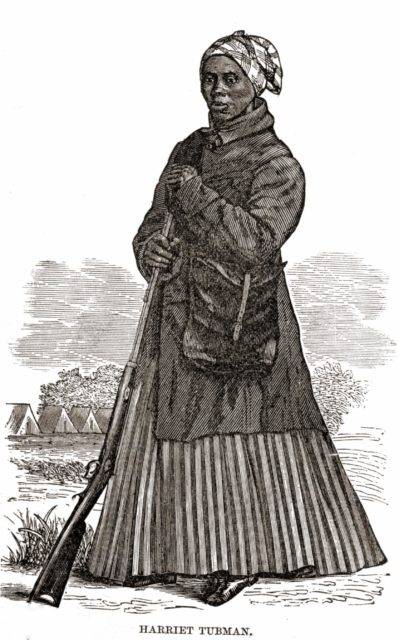

One example of a successful integration of army and naval tactics by Blacks and Whites occurred on June 1-2, 1863. On that night, Black Union soldiers under the informal yet quite effective command of Harriet Tubman and aided by the integrated crew of the USS John Adams raided Combahee Ferry on the coast of South Carolina. In addition to seizing and destroying great quantities of Confederate food and supplies, the raid liberated at least 700 enslaved persons, over 100 of whom joined the Union forces. The operation was the first time a woman had led an American military unit in battle.

In February 1865, on land and sea, Black soldiers and sailors helped the Union capture Charleston, South Carolina, the “Cradle of the Confederacy,” driving a stake through the heart of Confederate morale. One of the ships involved in the operation was the John Adams.

From the summer of 1864 to April 1865, Black soldiers fought in the critical and bloody Petersburg, Virginia, campaign that finally resulted in the capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond and the surrender of the main Confederate army.

Black soldiers so impressed their foes that near the end of the war, some White Southern officers urged the Confederate government to allow free Black men to join their army. In 1864, recognizing the courage of Black Union soldiers, Confederate Gen. Patrick Cleburne went so far as to call for the abolition of slavery.

It is not just the great quantity of people who die in war that is horrible; it is the great quality of those people who die. The Civil War was no exception to this tragic truth. The victories which came at a cost of hundreds of thousands of Black and White lives are what enabled Gen. Granger to come to Galveston to enforce the end of Confederate slavery on June 19, 1865. When he did so, this marked the end of the war caused by chattel slavery. With abolition came peace, two reasons for jubilation.

* Some estimates exceed 750,000, more than all other American wars combined.

** Even after the Civil War, enslavement of Native Americans occurred in California and other Western states. Although illegal under the 13th Amendment, the practice persisted.

Howard Isaac Williams is a writer and longtime member of ILWU Local 6 who is semi-retired from the messenger and pest control industries. He served as an aid worker in Afghanistan and Pakistan from 1989 to 1997. This piece originally appeared in The Howard Isaac Williams Newsletter. To receive the newsletter, email howardisaacwilliams@yahoo.com.