by Griffin Jones

Some say grassroots organizing in San Francisco’s District 10 has been a rudderless ship for years.

From the 1950s up to the ’90s, Bayview Hunters Point residents did a whole lot of work for the neighborhood, stepping in to act because the city wouldn’t — all independent efforts. They won millions in federal funding to replace their condemned homes. They blocked construction sites that wouldn’t hire Black workers. They shut down a polluting PG&E plant. They exposed fraud when a U.S. Navy contractor faked soil samples to show that the Hunters Point Shipyard was no longer highly radioactive, but clean and ready for upscale development.

In many ways, residents ensured that their neighborhood would resist gentrification for a long time. But, by the 2000s, the work of large-scale organizing fallowed — taken over by a web of nonprofits and Citizen Advisory Committees that only do so much.

Now, the Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council is taking its place at the helm of the ship. The council is an alliance of Bayview, Sunnydale and Fillmore residents along with local Black contracting groups and public housing tenant associations that have been steadily meeting for several years.

“Gone are the days we look to other people to take care of us,” said Council President Kenisha Roach in July. “We need the community to buy back into itself. It’s unity or death.”

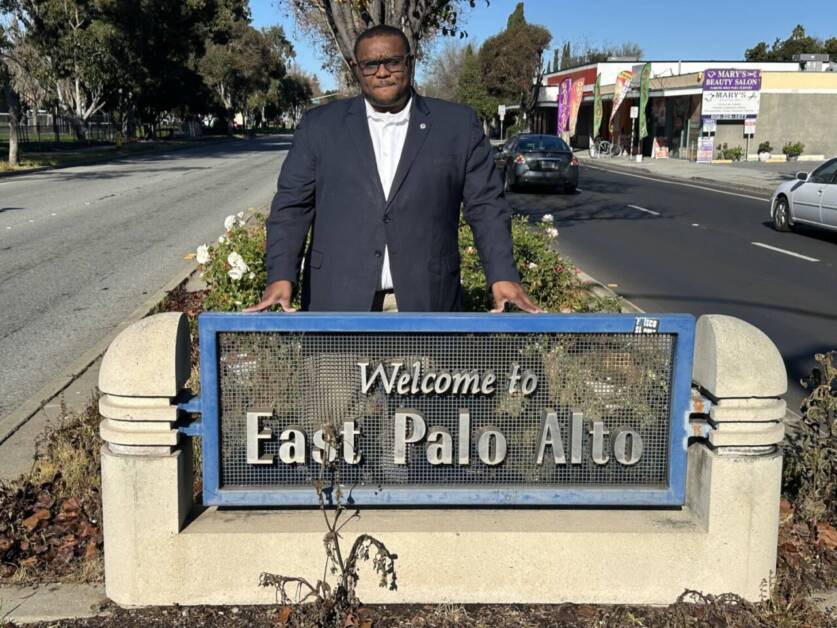

Elisha Rochell, Oronde Sterling, Evangela Brewster, Kenisha Roach, Tiree Pond and Kevin Williams first started meeting in June 2024. A year later, on July 15, they introduced themselves to the public as the Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council at the Ruth Williams Opera House on Third Street and Newcomb Avenue. The night drew a decent crowd from Districts 5 and 10.

“We didn’t invite the mayor,” treasurer Elisha Rochell told the room, looking around at the 50-plus attendees. “We didn’t invite our District 10 supervisor. We didn’t invite any organizations. We are here as us. And we need to talk.”

Locals aired their issues at a mic, discussing how they could petition for better living conditions at housing like Alice Griffith and how residents can gain from the billions of dollars of development coming to areas like Dogpatch and Candlestick.

Developers and their employees “live comfortably off the money that comes through Bayview Hunters Point,” said Elder Kevin Williams. Decades ago, Williams’ mother, Ruth Williams, ran classes in the building, and helped ensure the Opera House wasn’t demolished.

Since that town hall, the council has grown to a group of 30-plus members convening twice a month over fresh barbeque in the glossy new Southeast Community Center at Evans Avenue and Third Street, a symbol of the massive debt owed the neighborhood.

This group is highly organized. It’s entirely San Francisco natives. They follow Robert’s Rules of Order. It’s independent — not a nonprofit or formal organization. Members are young when it comes to grassroots work in District 10, many in their 30s and 40s.

Even so, elders are crucial to the council. It wouldn’t exist without their work. Each meeting includes insights on local history from people like Kevin Williams, Diane Wesley Smith, Claude Carpenter and Oscar James, well known advocates for Black San Franciscans since the 1960s, some who have continued with activism into their 80s.

“Our work is a testament to the meticulous and passionate leadership of our predecessors,” Roach told the SF Bay View, referring to the Big 5 of Bayview, an incredibly effective group of residents that formed in the 1960s and stayed independent for most of their lives.

Similarly, Rochell, Brewster, Roach and Sterling repeat at every meeting that they aren’t in anyone’s back pocket.

“We’re not gonna sell out,” said Sterling, the council vice president, on a windy day outside City Hall in July, taking a break between public comment periods. “We’re not gonna be in nobody’s back pocket.”

Each person has a day job or is retired. Nobody’s being paid for the work, and nobody has a billionaire behind them in the shadows.

A key commission for the Southeast

So, what’s the plan? For now, it’s packing commission meetings, starting with the Southeast Community Facility Commission.

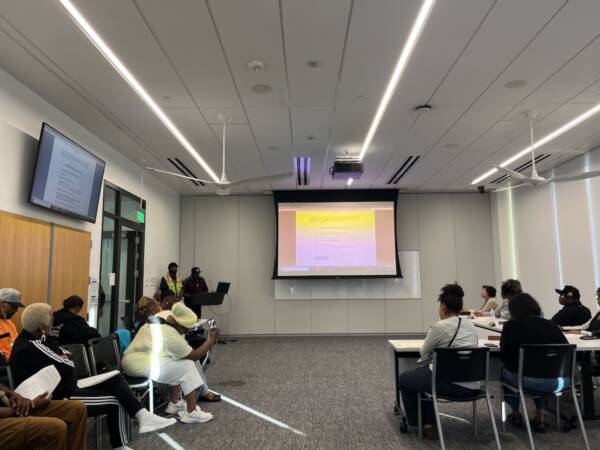

On Aug. 27, the council made a surprise appearance at the commission’s monthly meeting. A staffer had to run out and get several stacks of chairs for the 30-plus people who showed up to listen and say their piece.

The commission was initially started up in 2014 as part of a so-called Mitigation Agreement made between the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and Bayview residents, a reparative effort allowing the city to build the Southeast Sewage Treatment Plant in the 1950s, the largest sewage processor in the city, in exchange for strong promises of job and business opportunities.

The plant is just a few blocks up from the community center, where eastward winds carry the stench all over the area. It’s another polluter right in the middle of one of San Francisco’s only Black neighborhoods.

One of the main roles of the Southeast Community Facilities Commission is ensuring the SFPUC adheres to the conditions of the Mitigation Agreement — which includes legally binding rules to hire local and find ways development can benefit District 10.

“Community has teeth with SFPUC,” Evangela Brewster, the council’s sergeant-at-arms and an Alice Griffith resident, told the SF Bay View. “I believe it’s a commission that can really do things.”

One fear shared by Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council members is that some relevant commissions could be axed under Mayor Daniel Lurie’s overhaul of less active public bodies. The Southeast Community Facility Commission is among those. It canceled half of its 2024 meetings, and from 2020 up to 2024, meetings were held exclusively on Zoom with minimal public participation.

The commission is up for review on Sept. 17, when Mayor Lurie’s Commission Streamlining Task Force determines its value to the city. For now, the task force’s agenda states the group should be safe.

When the council quietly packed the Alex Pitcher room at 1550 Evans, commissioners looked flustered. By the end of the meeting, they had welcomed the change.

Commissioners Damien Posey and Chika Mezie — both Bayview natives — made commitments to advocate for more attention on District 10.

“I want everyone here to know that they have been heard, that they’re being heard,” Commissioner Posey told the room. “I want the same things everyone in here wants.”

Aside from Southeast Community Facility Commission meetings, Council members are packing the Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure Commission; Housing Authority Commission; Board of Supervisors; and several Citizen Advisory Committees that focus on the Hunters Point Shipyard and Candlestick Point.

A citywide movement

“We are here to represent 94124, 94134 and 94107 and [94117]. We are building back what was taken from us,” said Roach, opening a recent council meeting as night fell over the community center.

The Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council is part of a wave of grassroots efforts that have emerged in the last year across all those zip codes. They share members with the SF Hyper Local Building Trades Contractors Collective, a group that advocates for local Black contracting and hiring on billion dollar city contracts that are typically awarded to developers and contractors headquartered outside the city.

The collective meets weekly at the Southeast Community Center, with the typical 15-odd members placing tables into a square so they can face each other. Sometimes, meetings have reps from Associate Capital, Marinship and PCL Construction to present new job opportunities. But progress remains slow — for years, Hyper Local members have been petitioning for hard adherence to minority hiring standards. But with nobody monitoring the compliance end, numbers remain dismal.

Another group that shares members with the council is the Citywide HUD Alliance, which recently coordinated to bring Mayor Lurie to each public housing site in the city. HUD stands for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, a faltering agency that funded affordable housing for Black neighborhoods around the country destroyed by national urban renewal efforts.

Citywide is made up of tenants of San Francisco’s federally subsidized housing from Fillmore and Hayes Valley to Sunnydale, Potrero and Hunters Point. Often squalid living conditions and a minimal response from maintenance have compelled tenants to organize on their own behalf.

“We need as many eyes as we can have open,” Brewster told the SF Bay View. “I think sometimes a lot of people don’t realize what’s going on in their own community.”

Part of that, she added, is because the city has a pattern of ignoring them — Alice Griffith residents had called for action to address worsening living conditions for years, and it’s only now being discussed seriously at the city level.

“If they had listened to the community when we were talking about stuff, it wouldn’t be as bad as it is now.”

Brewster added that these problems pervade Black neighborhoods all over the city. “It’s not just Alice Griffith. From what I know it’s every community. It’s Oakdale, it’s Harbor, it’s Sunnydale, it’s Potrero.”

Even now, after touring cheap renovations and neglected complexes, city leaders say their hands are tied: Properties are managed by private companies, and there’s little government can do. But history has shown that city leaders will intervene when they want to — and when they’re pushed hard enough.

Bridging a decades-wide gap

Council leaders want to reconnect the community with the city — since the city hasn’t exactly done its part representing Black San Franciscans, what with the messy fallout from 2020’s Dreamkeeper Initiative. Much like the Big 5, who made their own way to Washington, D.C.. to win new housing in Hunters Point in the 1960s, council members are taking matters into their own hands.

Starting this summer, Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council members have been going to all the meetings they can go to that concern the city’s historically Black neighborhoods, including Potrero, Sunnydale, Fillmore and Bayview.

“There’s so many things that need to be addressed,” said Rochell, who is the council’s treasurer. “We’ve written letters. We’re going to the commissions, to public comment … And we’re watching the responses we’re getting and strategizing different ways to respond.”

Their workload is full. Aside from Southeast Community Facility Commission meetings, Council members are packing the Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure Commission; Housing Authority Commission; Board of Supervisors; and several Citizen Advisory Committees that focus on the Hunters Point Shipyard and Candlestick Point.

Veteran organizer Arieann Harrison, who runs the Marie Harrison Community Foundation — named for her mother, a legend in Bayview grassroots organizing — was pleased when she learned about the Bayview Hunters Point Coordinating Council.

Harrison said that staying on course and making connections with city reps will help the group sustain itself. She’s seen too many grassroots efforts fall to exhaustion and conflict.

“The key,” she said, “is to be together long enough to weave through the bullshit — and get ready.”

Griffin Jones is a freelance journalist based in San Francisco. She specializes in reporting on housing, discrimination, and criminal justice. Her work has appeared in the SF Standard, SF Bay View, Mission Local, and Hyperallergic. Griffin was born and raised in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley neighborhood.