by David Greenwald

Key points:

- Doubts raised over DNA evidence used to convict Kevin Cooper in 1983 Chino Hills murders.

- State review of DNA evidence was flawed, acting more like a prosecution brief.

- Unidentified male DNA found on key evidence, raising doubts about Cooper’s guilt.

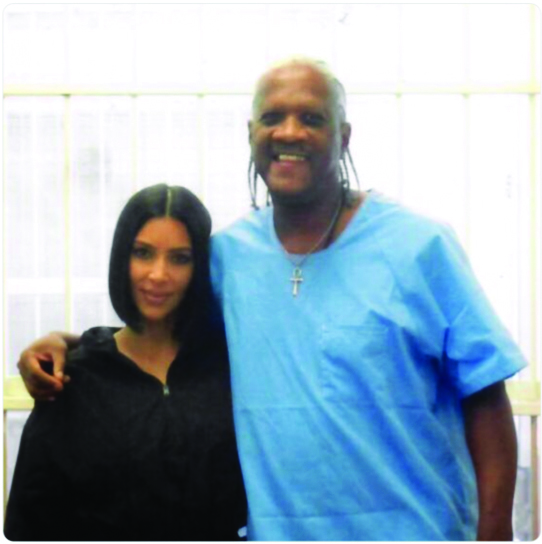

A growing chorus of legal experts, forensic scientists and civil rights advocates is raising new alarms over the integrity of the DNA evidence used to convict Kevin Cooper in the 1983 Chino Hills murders, arguing that the state’s review functioned more as a prosecution brief than a rigorous, good-faith inquiry into potential innocence.

In 2023, the law firm Morrison & Foerster LLP (MoFo) issued a report in its capacity as “Special Counsel to the Board of Parole Hearings” as part of the independent investigation ordered by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

The Special Counsel’s report hinges on a discredited DNA analysis conducted by Daniel Gregonis and endorsed by criminalist Alan Keel, whose conclusions have been widely criticized as scientifically unsound.

Cooper’s attorneys say that by treating that flawed evidence as definitive, the report then dismisses or contorts all other facts, arguments and new findings to align with a predetermined conclusion of guilt — forcing square pegs into round holes to preserve a deeply compromised narrative.

“The Special Counsel did not conduct a true innocence investigation,” Cooper’s legal team wrote in their formal rebuttal. “They re-packaged the prosecution’s case and ignored decades of contrary findings.”

Now, with Cooper still on death row, forensic discrepancies, chain-of-custody concerns, and ignored leads have emerged as central issues in what one federal judge called a potential wrongful execution.

A drop of blood with a broken chain

The state’s case at trial hinged in large part on a single drop of blood, labeled A-41, found in a hallway inside the Ryen family’s Chino Hills home. Prosecutors argued that DNA testing showed the blood came from Kevin Cooper, and used that finding to place him at the scene of the brutal 1983 murders. But that conclusion rests entirely on evidence for which the chain of custody is riddled with doubt.

The A-41 bloodstain was matched to a reference sample of blood — designated VV-2 — drawn from Cooper shortly after his arrest. Yet forensic experts and Cooper’s legal team say that the integrity of VV-2 was fatally compromised long before any testing took place.

For more than a decade, the vial containing Cooper’s blood sat unsealed in the possession of the San Bernardino County crime lab. It was only in 1995 — 12 years after the murders — that a tamper-evident seal was finally applied to the sample. During that time, no log, video, or notation system tracked who had access to the vial or when.

“Any opening and closing of the vial could occur undetected,” Cooper’s attorneys wrote in a statement. “The risk of contamination or tampering was ever-present.”

That risk, they say, became a reality.

Forensic analyst Dr. Mehul Anjaria, a DNA expert hired by Orrick on behalf of Cooper, reviewed the available data and determined that the DNA profile derived from the A-41 stain was markedly degraded, as would be expected from a decades-old crime scene sample. However, the DNA from the VV-2 vial remained undegraded and pristine — despite being older.

“The degraded DNA in A-41 does not match the undegraded DNA in VV-2,” Anjaria said. “That discrepancy is inconsistent with Keel’s claim that the blood was not planted.” Alan Keel was a purported expert that the law firm of Morrison & Foerster hired as part of its work.

In plain terms: if the drop of blood truly came from Cooper, and if the DNA in both samples originated from the same biological event, their degradation levels would be consistent. The fact that they are not suggests that A-41 may have been artificially created using Cooper’s blood — after the crime occurred.

Moreover, the defense notes, when Cooper’s blood vial was later re-tested by an independent laboratory, it revealed the presence of DNA from another individual—an inexplicable contamination in what should have been a single-source reference sample. The finding suggests that someone else’s DNA may have been introduced into the vial, either through mishandling or deliberate tampering.

Alan Keel dismissed concerns about the contamination, arguing in his 2023 report that small quantities of foreign DNA are not unusual in forensic settings.

But Anjaria called that explanation evasive and scientifically irresponsible.

“This is not a swab from a door handle or a shared surface,” Anjaria said. “This is the official reference sample for the most important piece of evidence in a capital case. It should be absolutely clean.”

Cooper’s attorneys have described the breakdown in evidence security as catastrophic.

“If DNA is supposed to be the gold standard of forensics, the chain of custody is its foundation,” they told the Vanguard. “And in Kevin’s case, that foundation was compromised beyond repair.”

A contaminated T-shirt and conflicting results

One of the most disputed pieces of physical evidence in the Kevin Cooper case is a tan Fruit of the Loom T-shirt discovered alongside a dirt road near the Chino Hills crime scene. Authorities claimed the shirt contained both Cooper’s blood and that of at least one of the murder victims — evidence they said tied him directly to the killings.

But early forensic testing told a different story. In 1984, the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department (SBSD) conducted serological tests on two distinct bloodstains found on different areas of the T-shirt. Only one of those results was ever disclosed, and it showed a blood type that did not match Cooper’s known serological profile. The result from the second test was never released. Notably, the T-shirt was never introduced at trial.

“Having failed to tie Mr. Cooper to the tan T-shirt, the Sheriff’s Department halted testing and kept the shirt out of evidence,” Cooper’s attorneys wrote. “That silence speaks volumes.”

Nearly two decades later, after Cooper’s appeals triggered post-conviction DNA testing, the shirt reentered the picture — but not without controversy. San Diego federal Judge Marilyn Huff, who presided over the testing, made a unilateral decision about which portions of the shirt could be tested for DNA. Cooper’s defense was not consulted, and experts say that decision critically limited the scope of analysis.

“This was not a neutral review of evidence,” said forensic scientist Dr. Mehul Anjaria. “The court controlled which sections of the shirt could be examined, and that selective testing undermines the credibility of the results.”

The analysis that did occur revealed something extraordinary: elevated levels of EDTA — a chemical compound used as an anticoagulant in blood collection vials — on portions of the shirt containing Cooper’s DNA. EDTA is not naturally present in the human body. Its presence on the shirt strongly suggested that the blood came not directly from a bleeding wound at the time of the crime, but from a laboratory-collected sample — specifically, from the vial labeled VV-2 that had been drawn from Cooper after his arrest.

According to Cooper’s team, “Five federal judges concluded that the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department likely planted Mr. Cooper’s blood on the T-shirt before the 2002 DNA tests were run.”

Those conclusions were supported at the time by Gary Siuzdak, a senior chemist for the Scripps Research Institute who was retained by the court in 2004 to independently test for EDTA. Siuzdak’s initial findings showed abnormally high levels of EDTA on the bloodstains — far higher than could be explained by environmental exposure or contamination.

But shortly after submitting his results, Siuzdak abruptly withdrew from the case, citing professional concerns. Keel, in his 2023 MoFo-backed report, dismissed Siuzdak’s work entirely, stating that EDTA testing is “not accepted by the forensic science community.” Anjaria, however, called that claim misleading and inaccurate.

“That’s wholly unscientific,” Anjaria said. “EDTA testing has been used in multiple legal settings, including in homicide and toxicology investigations. And Siuzdak wasn’t some fringe expert — he was highly respected, with one of the most credible labs in the country backing him.”

Beyond the chemistry, the shirt’s provenance raises further red flags. The tan T-shirt bore a striking resemblance to the one worn by Lee Furrow — the ex-boyfriend of Diana Roper — on the night of the murders, according to Roper’s sworn statement. Roper also turned over a pair of bloody coveralls she said Furrow was wearing, which she retrieved from their home the morning after the crime.

Rather than test the coveralls, the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department destroyed them. That decision was approved by an SBSD supervisor, Deputy Sheriff Kenneth Shreckengost — without notifying defense counsel, the court, or preserving any record of the contents.

“The shirt matched Roper’s description. The coveralls had blood on them. And yet none of it was investigated,” said an investigator. “Instead, the state focused on building a narrative around Cooper and ignored everything else.”

Despite these clear warning signs, the 2023 Morrison & Foerster (MoFo) report failed to even mention Roper’s statement or the destruction of the coveralls. No attempt was made to re-test the shirt for additional foreign DNA, and no witness interviews were conducted to determine how the shirt came to be near the scene or whether Furrow had access to similar clothing.

“The refusal to engage with that evidence wasn’t an oversight,” Cooper’s attorneys said. “It was a deliberate decision to exclude anything that pointed away from their theory of the case.”

The Fruit of the Loom shirt, once discarded as irrelevant, became a cornerstone of the prosecution’s post-conviction defense. But experts say it may instead be one of the strongest indicators that someone else — and not Kevin Cooper — committed the murders.

Unidentified DNA, ignored witnesses

One of the most alarming findings to emerge in post-conviction DNA testing was the presence of unknown male DNA on key pieces of evidence — including the tan Fruit of the Loom T-shirt and an orange towel recovered near the murder scene. According to court records and forensic lab reports, this DNA did not match Kevin Cooper, any of the four victims, or anyone else associated with the case.

Independent testing by Bode Technology, one of the nation’s most reputable forensic laboratories, confirmed the presence of foreign DNA on both items.

“Bode did extensive testing on certain evidence that revealed no match with Kevin,” Cooper’s legal team said. “This overwhelming evidence that failed to connect Kevin to the murders reveals that he was not the perpetrator.”

Rather than view these findings as cause for alarm, the MoFo report and state criminalist Alan Keel dismissed them outright. Keel speculated that the DNA might be “too undegraded” to have been deposited during the 1983 murders, implying that the items could have been contaminated in the years since. But forensic scientist Dr. Mehul Anjaria called that explanation unfounded.

“That’s pure conjecture,” Anjaria said. “There was no scientific basis to rule out the DNA’s relevance to the original crime. These unknown profiles should have triggered deeper investigation — not casual dismissal.”

Advocates argue the DNA findings should have spurred further testing, expanded CODIS database searches, or even the identification of alternate suspects. Instead, the foreign profiles were quietly sidelined in the MoFo analysis.

The missed opportunity is even more significant given the nature of the crime itself. The original coroner’s report determined that the murderous attacks took no more than four minutes and involved at least three weapons — a hatchet, an ice pick or similar sharp object, and a knife. With 144 wounds inflicted on the four victims, one of whom was a physically strong, adult male U.S. Marine veteran, the coroner concluded there must have been multiple assailants.

That conclusion was supported by early statements made by the lone survivor of the attack — 8-year-old Josh Ryen. In the immediate aftermath, Josh told both medical staff and law enforcement officials that three white or Latino men were responsible for the attack on his family. He consistently repeated those statements during his early hospital stay and they were documented in multiple contemporaneous police reports and hospital records.

At least nine separate witnesses later came forward to confirm that Josh made those statements, including relatives and emergency responders. Yet not a single one of those witnesses was interviewed as part of the MoFo review.

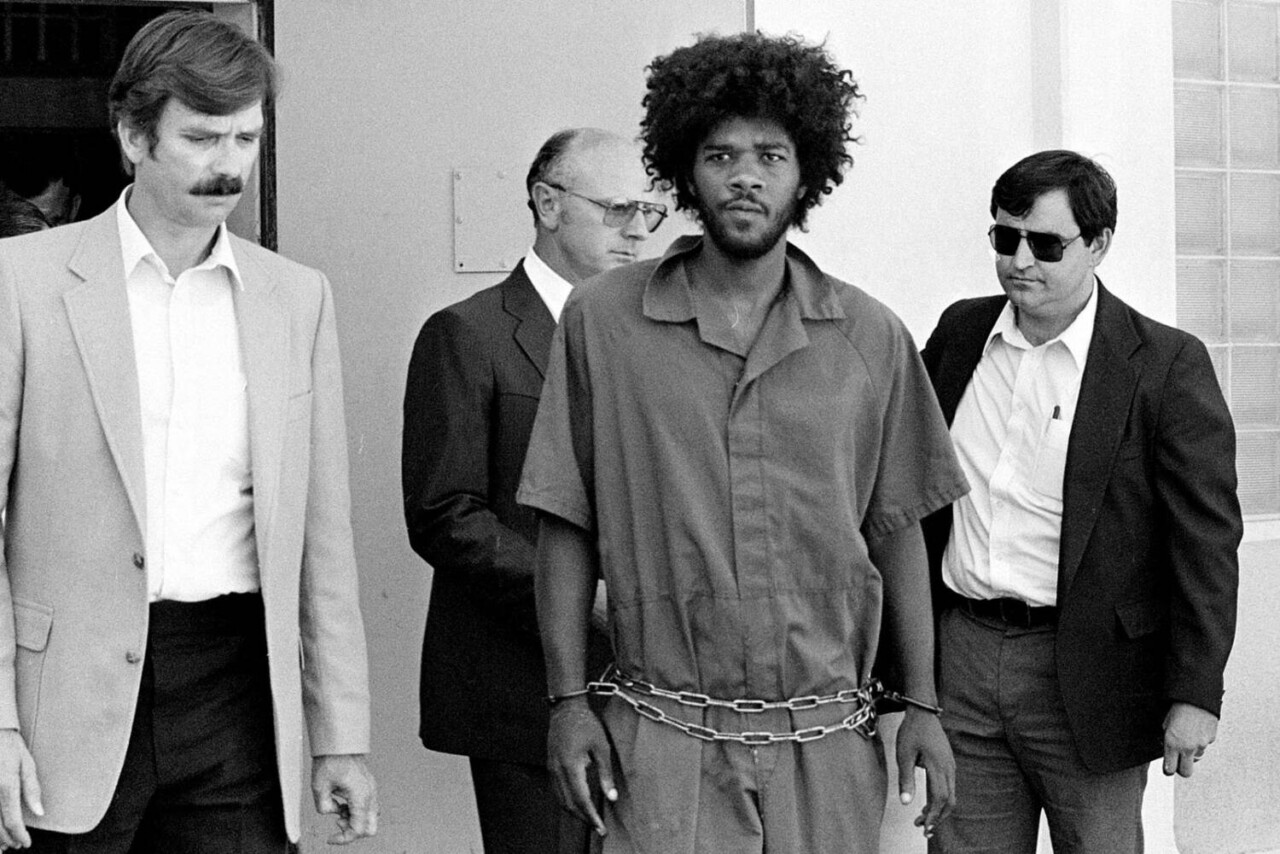

In subsequent weeks, Josh — still hospitalized and suffering from severe injuries — was subjected to almost daily suggestive questioning by detectives. Under this pressure, and after months of hearing about Cooper in the news, he began to change his account. Cooper, a Black man who had recently escaped from a nearby minimum-security facility, quickly became the focus of the investigation.

“This is the heart of the problem,” said an attorney. “A traumatized child’s early recollection of three white or Latino assailants was ignored, overwritten, and ultimately erased from the official narrative. That’s not justice. That’s tunnel vision.”

Disappeared evidence and misleading testimony

The evidence handling in the Cooper case was marked not only by oversight and contamination — but by outright disappearance.

Shortly after the murders, a blue short sleeved shirt stained with what appeared to be blood was recovered by a sheriff’s deputy near the Canyon Corral Bar, not far from the crime scene. A blue shirt had been worn by one of the three suspects described in the Criminal Bulletin issued by the SBSD right after the murders. But the existence of the blue shirt was never disclosed to the defense and it has vanished from the records of the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department and has never resurfaced.

Around the same time, Roper turned over a pair of bloody coveralls to the SBSD that she said Furrow had worn on the night of the murders. Rather than submit the coveralls for testing, the sheriff’s department destroyed them. That destruction was authorized by Deputy Sheriff Ken Shreckengost without notifying Cooper’s defense or seeking judicial approval.

And there was more. A bloody knife being cataloged — possibly used in the attack — was recalled by a court clerk during a post-trial review but no such knife was ever entered into evidence or documented in official records. No explanation was given, and no one was ever held accountable.

“This wasn’t just sloppy work,” said one private investigator involved in the case. “This was evidence that could have exonerated Kevin Cooper, and it was erased.”

The forensic record was further marred by misconduct from the state’s own analyst, Daniel Gregonis. Tasked with testing A-41 — the bloodstain recovered from the Ryen home that prosecutors said matched Cooper — Gregonis used Cooper’s own reference blood sample on the same testing slide, creating a dangerous risk of cross-contamination. He later altered his bench notes to make the A-41 sample appear consistent with Cooper’s enzyme markers — after receiving Cooper’s known blood profile.

In 2003, Gregonis testified under oath that he had never removed A-41 from its envelope in 1999. But lab records later proved otherwise. He had, in fact, accessed the evidence at that time.

“This wasn’t an honest mistake,” said an investigator who reviewed the lab’s handling procedures. “It was deception that directly influenced the outcome of a capital case. That should scare everyone.”

Despite all of this, neither Gregonis’s altered notes nor the missing and destroyed evidence were meaningfully addressed in the MoFo report. No interviews were conducted with key figures involved in the mishandling. No effort was made to account for the blue shirt, the coveralls, or the unlogged knife.

Instead, the Special Counsel’s office concluded that the evidence of Cooper’s guilt remained “extensive and conclusive.”

But for those who have followed the case for decades, that conclusion feels like a whitewash.

“We’ve got foreign DNA. We’ve got destroyed evidence. We’ve got lab misconduct,” said one legal expert. “If that doesn’t warrant a new investigation, what does?”

A misguided report, critics say

Despite glaring inconsistencies, compromised evidence, and unresolved forensic anomalies, the 2023 report by Morrison & Foerster LLP — commissioned by California’s governor — concluded that “the evidence of Kevin Cooper’s guilt is extensive and conclusive.” That conclusion has been met with a torrent of criticism from legal scholars, forensic experts, and advocates who have spent years reviewing the case.

Private investigator Grant Fine, who worked extensively with Cooper’s defense, characterized the report as fundamentally unserious. “This wasn’t a review. It was an audit of old paperwork,” Fine said. “They didn’t interview key witnesses. They didn’t investigate alternate suspects. They ignored critical forensic contradictions. This wasn’t about finding the truth — it was about reaffirming a conviction that should have been under full scientific and legal scrutiny.”

The report relied heavily on the original trial record from 1984 and post-conviction materials pre-selected by the state. MoFo attorneys did not interview law enforcement officers such as the deputy who picked up the blue shirt and who was questioned in court about the discovery and whereabouts of that evidence. They did not speak to Germaine Cook or Dan Green, who reported seeing the Ryen family’s stolen station wagon being driven by three white men the day after the murders. Nor did they contact any of the nine witnesses who confirmed that Josh Ryen, the sole survivor, originally identified the killers as white or Latino.

“They didn’t ask hard questions,” said a former public defender familiar with innocence cases. “They asked safe ones — ones that wouldn’t disturb the state’s narrative.”

Equally troubling was the Morrison & Foerster investigation’s failure to probe systemic misconduct. Cooper’s legal team identified at least eight major deficiencies in the review, including the failure to investigate police and prosecutorial misconduct, to follow up on destroyed or missing evidence, or to consider the role of racial bias in the original investigation and prosecution. Notably, the team also ignored documented Brady violations — instances where potentially exculpatory evidence was withheld from Cooper’s original defense.

“There was no meaningful exploration of the possibility that the state suppressed evidence that could have helped Kevin,” said one attorney who reviewed the findings. “That’s an essential question in any innocence case, and they skipped it.”

Transparency issues further undermined the credibility of the report. Cooper’s attorneys were not informed that Morrison & Foerster had retained Alan Keel as its forensic expert until after the report was completed. Keel, a former state criminalist with ties to the same law enforcement agencies involved in Cooper’s prosecution, was not vetted or cross-examined by any independent reviewer. His previous public writings had suggested strong deference to law enforcement and skepticism toward defense-based innocence claims.

“That’s not an independent expert,” said Dr. Mehul Anjaria. “That’s someone who was handpicked to reinforce a conclusion that had already been decided.”

Even Keel’s scientific methods came under fire. His report downplayed or ignored concerns about the chain of custody, dismissed unexplained DNA findings, and declared EDTA testing to be “not accepted” by the forensic community — despite its documented use in multiple legal proceedings and lab environments.

The report also failed to account for changes in forensic science and legal standards that have occurred in the four decades since Cooper’s trial. It treated decades-old testing procedures as conclusive, even though contemporary experts now view some of those methods — such as serology without DNA typing or enzyme marker matching without blind controls — as deeply unreliable.

“Scientific rigor means you go where the evidence leads, even if that means re-evaluating the entire case,” said Anjaria. “The MoFo (Morrison & Foerster) report didn’t do that. It stopped at the surface.”

Perhaps most damaging was the overall tone and framing of the report. Critics say it reads less like an independent investigation and more like a legal brief defending the original conviction. Nowhere did the report seriously grapple with the possibility that Cooper may be innocent. Nowhere did it weigh the accumulation of anomalies — contaminated evidence, destroyed leads, altered lab notes — as a pattern pointing to injustice.

“The report was never designed to test the conviction,” said one advocate. “It was designed to preserve it.”

For Cooper and his supporters, the Morrison & Foerster report represents a squandered opportunity — one that failed to meet the moment, ignored the science, and deepened public distrust in the fairness of California’s criminal legal system.

“It was a report written for the state, by the state, to protect the state,” Cooper’s team concluded. “And in doing so, it abandoned the fundamental question Gov. Newsom asked: Is Kevin Cooper innocent?”

A District Attorney focused on conviction

San Bernardino County District Attorney Michael Ramos remained a vocal opponent of any new review throughout his tenure. He frequently cited the presence of Cooper’s DNA in the house as proof of guilt — even after serious questions were raised about the validity of the forensic evidence.

“Ramos wasn’t seeking justice. He was seeking vindication,” said one investigator close to the case.

Ramos’s office opposed new testing on the knife, refused to release evidence requested by Cooper’s defense, and failed to disclose the blue shirt found after the murders.

“The mindset was clear,” the investigator added. “Admit nothing, concede nothing, protect the conviction at all costs.”

Mounting expert consensus

A series of federal judges, legal scholars, and forensic scientists have expressed alarm about Cooper’s case. Among the most prominent was Ninth Circuit Judge William Fletcher, who in 2009 wrote a dissenting opinion that began: “The State of California may be about to execute an innocent man.”

Paula Mitchell, a former Loyola Law School professor and director of the Project for the Innocent, said the DNA in Cooper’s case is anything but definitive.

“DNA testing is just one tool, and it has to be done absolutely correctly to have any merit,” Mitchell said. “The DNA testing in Kevin’s case is absolutely flawed.”

Anjaria, who reviewed the full forensic record, put it more bluntly: “All of the credible evidence in this case points to multiple killers and that Kevin Cooper was not involved. Yet the state continues to rely on compromised science and suppress relevant information.”

A final chance at justice?

Despite the mounting evidence and calls for intervention, Cooper remains on death row.

Although Gov. Newsom initially ordered an innocence investigation, he has since accepted the Morrison & Foerster report, which many critics argue merely recycles prosecution narratives while ignoring substantial new evidence.

Advocates note that if the governor truly intends to fulfill the spirit of his executive order, he should commission a new and independent investigation — akin to the one conducted by Reed Smith in the Richard Glossip case. So far, however, Newsom has shown no indication he is willing to do so, for reasons that remain unclear.

“This wasn’t just a bad investigation,” one member of the defense team said. “It was an opportunity to correct a terrible wrong — and the state squandered it.”

The consequences could be irreversible.

“This was never about resolving uncertainty,” Anjaria said. “It was about cementing a narrative. But the evidence, when scrutinized scientifically, does not hold up.”

As new DNA technologies emerge and untested evidence still exists, supporters say the state still has time to get it right.

But for Kevin Cooper, time may be running out.

David Greenwald is the founder, editor, and executive director of the Davis Vanguard. He founded the Vanguard in 2006. David Greenwald moved to Davis in 1996 to attend Graduate School at UC Davis in Political Science. He lives in South Davis with his wife Cecilia Escamilla Greenwald and three children. This story first appeared in the Vanguard and is republished with permission.