by Billy X Jennings

Recently, I was reading an article in Ramparts magazine about the Soledad Brothers in 1971. Coupled with the recent death of David Johnson, a friend of George in San Quentin and a member of the San Quentin 6, I began to think about my involvement in the Jackson brothers’ funerals.

I was working at Central Headquarters of the Black Panther Party when George Jackson was murdered by guards at San Quentin Prison. I had never met George personally, but I knew his mother and sister, who worked closely with the Party. They ran the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee. I met his younger brother Jonathan once when he and Angela Davis came by Central HQ. We spoke briefly.

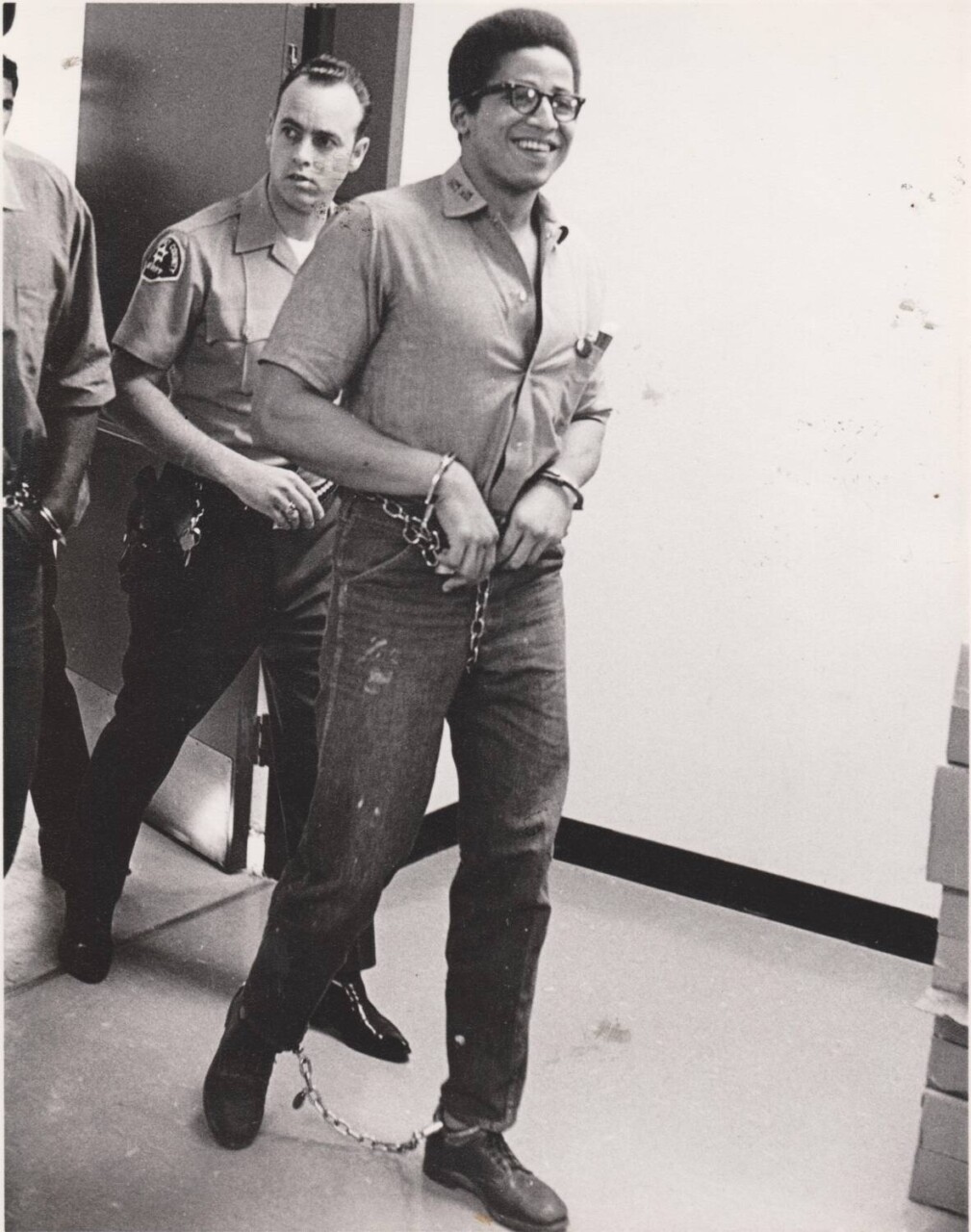

In early 1971, members of the BPP would go to court to show support for George, Fleeta Drumgo and John Clutchette during their trial for the alleged murder of a prison guard at Soledad prison – The Soledad Brothers trial.

George Jackson was one of the leaders of the developing Prison Rights Movement at that time. He helped develop a new consciousness among prisoners based on political education, service to the community and the destruction of the evil capitalistic system. George was field marshal of the Black Panther Party. He had a gift for writing and had two books published. He had a clear analysis of how the evils of capitalism affected our community.

George was loved by all Party members. When he was murdered by prison guards in San Quentin, many Panthers wanted to take up arms to avenge his death. I was one of them. We were ready, but we were directed by the Central Committee to chill out and stay focused on the larger, protracted struggle.

One of my duties at that time was security for the Party. I had worked as security for Huey P. Newton and other members of the Central Committee. I was selected to be a pallbearer for George. Other pallbearers were Sam Castle, Bobby Bowen, Alden, Tick and Darrell. I had also been a pallbearer a year earlier when George’s brother Jonathan was killed in Marin County.

On the day of the funeral, we arrived at St. Augustine’s Church around 9:30 a.m. We were in full uniform, which we only wore on special occasions. It was a very busy morning. Panthers were lined up from the church on 27th and West to the next block. We had traffic detour signs put up because West was a busy street and soon would be filled with people.

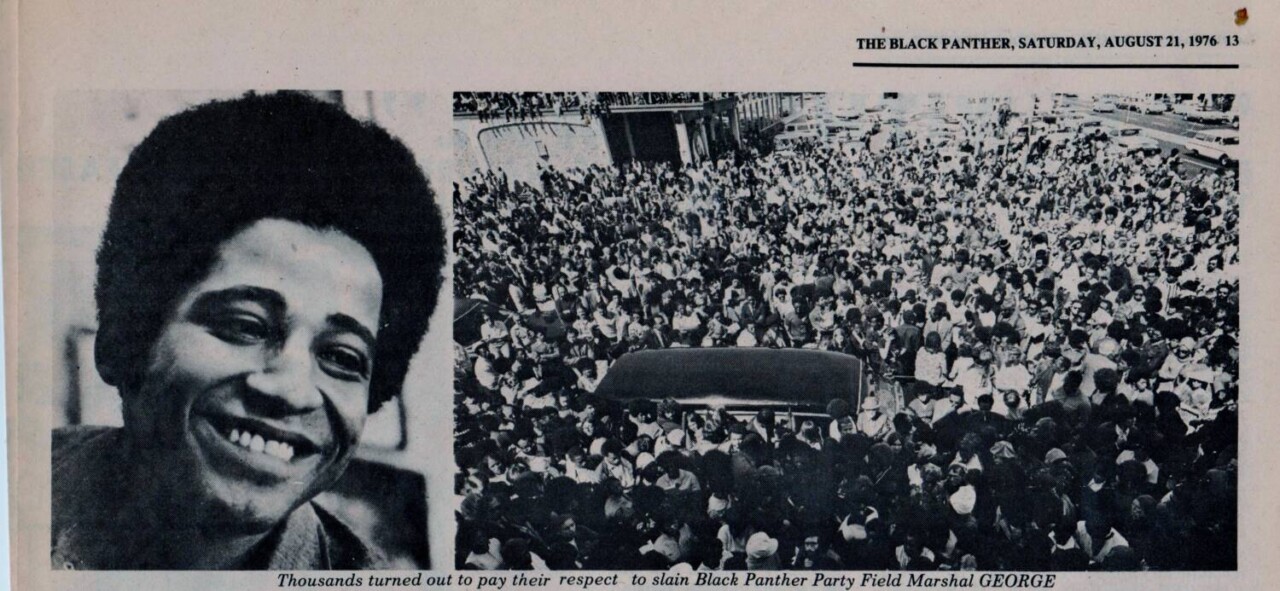

There were about 200 Panthers in uniform present, including our children. The Panther flag was flying high above us out of a church window. People in the community also loved George Jackson and over 8,000 people filled the streets around the church.

Inside the church, I saw Georgia and Lester Jackson, George’s parents, as well as his sister Penny and other family members. I looked at Huey, Bobby and Masai and they all had a pained expression on their faces. Huey, Bobby, Masai and Father Neil all spoke. Bobby had recently been released from prison. Elaine Brown sang one of her songs. The whole ceremony was very somber.

It was then that I made up my mind that I would always be a revolutionary until I die. I owe that to brothers like George and Jonathan who gave up their lives and to those brothers who went to prison.

The church held only about 200 people, so speakers were placed outside for the thousands to hear the service. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house, yet everyone also felt empowered by the spirit and strength of George.

We rose to pick up George’s body, and everyone raised their fists in the air as we filed past them. When the doors opened and we stepped outside with the body, I saw that the crowd had grown tremendously. There were people on rooftops, hanging from telephone poles and filling the streets. Everyone raised their fists in the air and chanted “Long Live George Jackson.” It was a sight that could set a fire in your heart.

We placed George’s body in the hearse and the Panthers outside cleared a way through the crowd. I was asked to ride with the family. The rest of the pallbearers walked in front of the cars. As we followed the limo, I looked out the window and all I could see was a sea of fists – black, white and brown. It was a beautiful sight. People were chanting as we drove off.

There was a long caravan of cars following the body to the airport. Along the streets, people showed their support and we all participated in the first Black August event. In 1972, after George was murdered in San Quentin, the remaining Soledad Brothers were acquitted of the murder charge.

The following poem was featured in George’s memorial pamphlet:

If We Must Die

If we must die let it not be like hogs,

hunted and pinned in an inglorious spot,

while around us bark the mad and hungry dogs

making their mock at our accursed lot;

If we must die then let us nobly die,

so that our precious blood may not be shed in vain.

Then even the monsters we defy

shall be constrained

to honor us though dead.

We kinsmen must meet the common foe,

though far outnumbered, let us show us brave,

and for their thousand blows,

deal one deathblow.

What though before us lies the open grave,

like men we’ll face the murderous pack,

pressed to the wall, dying,

but fighting back.

by Claude McKay, 1919

Black Panther historian Billy X Jennings administers the archives documenting the history of the Black Panther Party. Some of the treasures can be seen at https://www.babylonfalling.com/billyx.html. He can be reached at itsabouttime3@juno.com. This article is from his upcoming book, which will be released in 2026.