by Matthew Jackson

BART leaders quickly selected the Oakland-based law firm, Meyers Nave, to carry out the investigation. At the time, this action failed to prompt a close look at the firm’s background, practice areas and clientele.

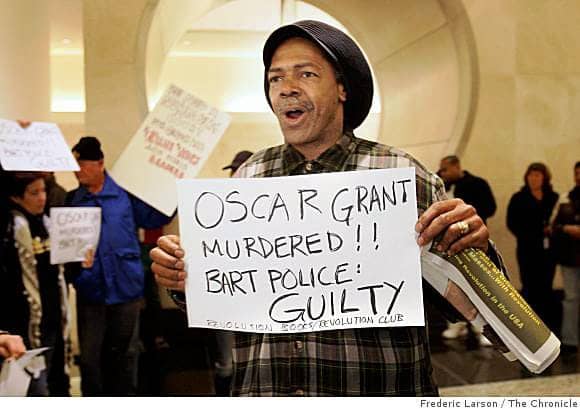

An examination into Meyers Nave’s work on the Oscar Grant case and its work for various police departments around the state, reveals a firm that is anything but an independent third party. Meyers Nave is instead a law office deeply intertwined with municipal governments and police forces. Its lawyers strongly identify with government clients who account for all of the firm’s business.

Managing BART’s crisis

BART executives greeted the report as a welcomed reform tool. “I appreciate their efforts,” said BART Board President Thomas Blalock, “which I believe are helping to open a new chapter in our continuing efforts to improve police services at BART.” BART board member Carole Ward Allen greeted the report, calling it “a very valuable tool that will help us to improve BART’s efforts to keep our system safe for all riders while helping to prevent such incidents in the future.”

The report’s purpose, apparent in the operative language used in it and echoed by BART’s executives, was to “improve police services” and “improve BART’s efforts” to make the “system safe.” Somehow these became the goals of the internal affairs report – not investigating allegations of systematic BART police misconduct and abuses of power related to Grant’s slaying.

Even so, critics of the BART police initially welcomed the Meyers Nave report, highlighting some of the findings that generally supported their own research and observations regarding widespread abuses by BART officers against riders, particularly youth of color. In the end, however, Meyers Nave’s “independent” investigation failed to rock the boat, almost as if by design.

A closer look at the Meyers Nave law firm reveals that this was entirely by design.

‘Farmed out’

Attorneys Steve Meyers and Michael Nave created the firm in 1986. At the time, Meyers was the city attorney for San Leandro. In 1985, he sent a memo to the City Council calling for a “reorganization of the city attorney’s office,” the gist of which was to privatize the city attorney’s office. He called for the city’s law office to be “farmed out” in order to save money for San Leandro.

In recent years, Meyers Nave has racked up an impressive list of victories defending police departments against lawsuits brought by individuals and family members of those who have alleged abuse and civil rights violations at the hands of officers. Representative examples drawn from Meyers Nave’s own website include:

“Martinez v. City of Fairfield. Plaintiff Martinez, a 13-year-old boy, alleged civil rights violations by Fairfield officers after being struck in the face numerous times during an arrest. The jury returned a complete defense verdict, finding that the officers acted appropriately.

“Shepherd v. City of Modesto. The plaintiff filed suit alleging wrongful arrest, excessive use of force and false imprisonment following her arrest by Modesto officers. The federal jury returned a complete defense verdict.

“Pascual v. City of Los Angeles. We obtained summary judgment in favor of all defendants, including the City of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Police Department and the police chief on claims of civil rights deprivation, discrimination, hostile work environment and retaliatory discrimination.

“Creal v. City of Fairfield. The plaintiff brought a federal civil rights excessive force claim against the City of Fairfield and two individual officers. After deliberating for less than four hours, the jury came back with a complete defense verdict on all state and federal counts.”

In advertising materials, Meyers Nave’s attorneys talk about “controlling the crisis” and “creating a legal and public relations action plan” in the aftermath of situations such as police shootings. Today, Meyers Nave advertises its role in the BART internal affairs investigation into Grant’s shooting as a successful example of its approach to “crisis management.”

Going on the offensive: gang injunctions and less-than-lethal force

Meyers Nave is mostly a defense counsel, hired by cities and their police departments to prevent investigations into official misconduct from blowing up and to contain potentially costly judgments in civil rights, environmental and labor cases. But the firm is also involved in crafting policies sought by tough-on-crime politicians and police forces.

In June of 2010, Meyers Nave was retained by then City Attorney John Russo to represent Oakland in its successful effort to impose a gang injunction in the Fruitvale neighborhood and in another effort to prepare an injunction in “Area 3,” a neighborhood also in East Oakland.

Unlike its role in the BART internal affairs investigation, Meyers Nave’s work for the City of Oakland has been subjected to some scrutiny by community members and journalists. In February, before court hearings to consider the Fruitvale injunction, the grassroots coalition Stop the Injunctions asked “whether the private law firm of Meyers Nave should be allowed to sue the defendants on behalf of the people of the state of California?”

Such spirited work to promote police initiatives like the gang injunctions seem to contradict the notion that Meyers Nave is an “independent” or “outside” entity, capable of objectively conducting investigations of police shootings such as that which ended in Oscar Grant’s death.

Lead attorney in the Fruitvale gang injunction Tricia Hynes has promoted injunctions in publications like American City and County and The Recorder. Both are influential magazines read by many government officials. In her op-ed piece in American City and County, Hynes claims gang injunctions are “absolutely” effective: “Carefully crafted gang injunctions can decrease gang-related criminal activity.”

She cites studies providing evidence that crime rates have fallen after the imposition of some injunctions in Los Angeles and other cities. Evidence is still sparse and much of the existing research is in disagreement on the effects of injunctions, however.

In an article entitled “Gang Injunctions Make Neighborhoods Safer,” Hynes makes a kind of sales pitch to readers: “The reason why more and more cities are considering gang injunctions is that they work.”

Hynes, who was made a principal attorney at Meyers Nave in 2008, is one of the firm’s lawyers specializing in the defense of police accused of brutality and civil rights violations. Her clients have included the police forces of San Leandro, South San Francisco, Petaluma, Fairfield, Milpitas, Union City and other Bay Area cities.

Beyond the courtroom, she has published papers on subjects like how to “Avoid or Reduce Litigation Costs – Critical Steps Police and Other Departments Can Take” and how police forces can defend themselves in “In-Custody Death Cases involving Tasers,” “Excited Delirium” and “Positional Asphyxia.”

In arguing for the Fruitvale gang injunctions, Hynes was described as forceful and passionate in court. Oakland’s contracts with Meyers Nave were for $40,000 to prepare and litigate each gang injunction targeting Fruitvale and “Area 3” in far East Oakland.

City Attorney Russo has since resigned to take the position of City Manager in Alameda. Alameda has reportedly retained Meyers Nave as counsel in 2011.

Bay Area writer Matthew Jackson can be reached via editor@sfbayview.com.