On a cloudy Saturday morning in August, the sidewalk outside Glenn E. Dyer Jail in Oakland seems an odd site for a voter registration drive – but organizers are targeting an atypical audience: inmates and those visiting them.

“You’ve got the right and reason to register to vote in this election and so do the people you’re coming to visit,” says Linda Evans as two women approach the jail entrance. Evans is co-director of the San Francisco-based non-profit All of Us or None, which organized the Aug. 16 Day of Action to raise awareness of voting eligibility and counter what they call “widespread confusion about inmates’ legal voting rights.” Chapters throughout the state held drives in Alameda, Sacramento, Orange, San Mateo, Los Angeles and San Diego counties.

“Laws that directly affect inmates will be decided this November, so please share this information and encourage them to vote,” Evans continues.

“Wait,” one woman says, slowing her pace. “You mean they can vote while they’re in jail?”

“Wait,” one woman says, slowing her pace. “You mean they can vote while they’re in jail?”

“Yes they can,” says Evans. “It’s the law.”

A law that is hardly clear. After years of disagreement and legal wrangling, authorities at every level still disagree about the voting rights of California’s more than 82,000 jail inmates – most of whom are Black or Latino, and have not been convicted of any crime. Less than three months before one of the most historic elections in national history, California is still without a clearly established policy on jail inmate voting – and “the law” seems to vary with who you ask.

Ten California counties hold about 70 percent of the state’s jail inmates, but calls to the registrars of voters in each of these counties yielded a variety of opinions on whether or not those inmates can vote. Representatives from four counties, including San Diego and Alameda, stated that inmates cannot vote under any circumstances; four other counties, including Fresno and Sacramento, said inmates with felony convictions were disenfranchised; Orange County’s registrar’s office said that jail inmates are eligible to vote as long as they are citizens; and in Los Angeles County – which holds the nation’s largest jail population of 19,000 – a registrar employee admitted to not knowing what voting rights jail inmates held and suggested calling Secretary of State Deborah Bowen.

In June 2004, San Francisco non-profit Legal Services for Prisoners with Children asked then-Secretary of State Kevin Shelley to clarify the voting rights of those in jail and on probation and learned that both groups were eligible to vote. In November 2005, new Attorney General Bill Lockyer officially denounced Shelley’s interpretation, declaring those on probation and in jail for a felony to be legally disenfranchised.

All of Us or None, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and several other organizations took the debate to court. In December 2006 the California Court of Appeal sided with the activists, ordering the secretary of state to inform election officials that “the only persons disqualified from voting are those who have been imprisoned in state prison, or who are on parole as a result of the conviction of a felony.”

Following the 2006 decision, the secretary of state’s office complied by informing county registrars that only those “in prison or on parole for a felony” were ineligible to vote – but did not fully explain what that meant for those held in jail, creating a network of state elections officials who disagree amongst themselves.

According to the secretary of state’s lawyers, individuals serving a jail sentence following a felony conviction cannot vote, while those in jail for a misdemeanor or awaiting trial can. Organizations like the ACLU, All of Us or None and Berkeley-based Voting Rights for All and even the county of San Francisco take a different stance, arguing that the 2006 Appeals Court decision enfranchises even those jail inmates who have a felony conviction.

The confusion may ultimately boil down to the precise meaning of “a felony sentence.” According to Peter Sheehan, an attorney with the Social Justice Law Project who served as co-counsel in the 2006 case, the decision holds that someone sentenced to jail for a felony is incarcerated as a condition of felony probation, and not technically serving “a felony sentence.” That makes the actual number of disenfranchised jail inmates very small. Or it would, if the average citizen – or public official – understood that distinction. “If the Secretary of State is simply saying people in jail for a felony cannot vote, that’s a misrepresentation unless they follow up with a detailed explanation of the distinction between felony probation and a felony sentence,” Sheehan said.

Ultimately, most jail inmates’ rights do not hinge on the outcome of that particular disagreement. According to state data, more than two out of three California jail inmates have not yet been convicted of any crime and would qualify as potential voters even under the secretary of state’s own reading of the law – though four of the 10 county registrars polled believed all jail inmates were ineligible to vote.

“If most people in jail haven’t been convicted, the state already agrees that most people in jail can vote,” said Evans. “So why isn’t there some kind of institutionalized procedure to make that easier and to make that known?”

According to a legal representative from the secretary of state’s office, the state is only required to inform counties of the law, while each county registrar is responsible for ensuring that employees correctly follow it. Sheehan believes the state has a duty to do more.

“Let’s say we were talking about women or Catholics or Blacks, instead of people in jail,” he said. “We all know these groups can vote under the law. If some counties wouldn’t let them, we’d expect the state to take action, whether it involved making phone calls or holding a training. This should be no different.”

But it is different. “The misinformation is widespread and goes all the way to the top,” said Judy Gerther, a co-chair of Voting Rights for All, who coordinated volunteers to register voters outside of Oakland’s county courthouse in 2004. “There were judges we ran into then who read our materials on eligibility and said, ‘We don’t believe you.’ This has been the law since 1973, but it’s never been publicized or clarified in layperson’s language. Lawyers don’t know; judges don’t know.”

Along with this month’s Day of Action, grassroots efforts to raise awareness have included a Northern California ACLU billboard campaign and All of Us or None lobbying state officials for better education and enforcement. As in 2004, Voting Rights for All plans to conduct outreach outside several Bay Area courthouses in mid-September. All of Us or None and the ACLU have sought a meeting with Secretary of State Deborah Bowen for several months, peaking in April when All of Us or None led a protest on the state capitol. That meeting hasn’t happened.

When it comes to inmate voting, jail facilities are no more regulated than county registrars. Don Allen of California’s Correctional Standards Authority, the agency responsible for designing state jail and prison policies, admits there are no mandated procedures for providing inmates access to voting information. “We have a broad rule that jails need to have some kind of policy to accommodate inmates’ right to vote,” said Allen. “The onus is on the county to design procedures that fulfill that obligation. Some may do the minimum and some may do more.”

For some, that minimum is far too low. “Many individuals in jail have no reason to think they can vote and little chance of receiving accurate information if they ask,” said Kathy Kahn, a retired defense attorney and Voting Rights for All co-chair. “Until we can assure accurate information is available, we don’t know how many inmates don’t want to vote and how many are being incorrectly told they can’t.”

“Even if the law says inmates can vote, they’re in jail. They’ve got bigger problems and priorities,” said Michael Robinson, an Alameda resident perplexed by the campaign to secure inmates’ rights he’s not sure they want. “My nephew talks to me about all kinds of stuff when I go see him in jail, but he’s never asked me to help him sign up to vote.”

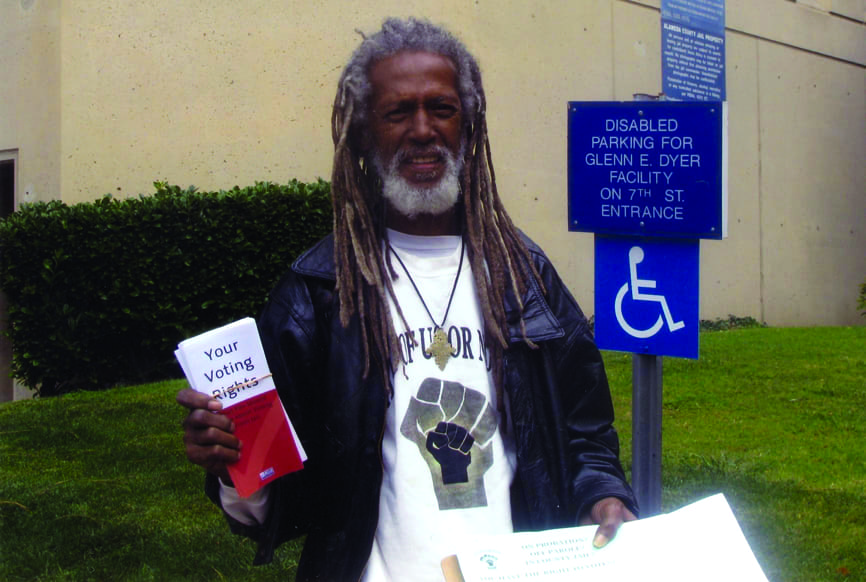

Activists argue that this is not a question of whether or not inmates want to vote or who they will vote for. “I don’t think most people in jail understand the power of their voting. They often think voting won’t change anything,” said All of Us or None member Elder Freeman. A former Black Panther and state prisoner, Freeman fears many in jail today don’t know what voting can accomplish.

“Getting them the vote is just the first step,” he said. “We need to teach them it’s not all about federal elections. State and local elections determine policies in the communities where they live.”

Though All of Us or None has sought support for this issue from the state Democratic Party with little success, Nunn emphasizes that defending the voting rights of those in jail is about civil rights, not partisanship.

“Nobody I try to register ever says, ‘Oh, I can’t vote because I’m Black,'” said Nunn, also a former prisoner. “But I get plenty of Black and Brown people who falsely believe they can’t vote because they’re on probation or have a felony conviction. I know there are plenty of Black and Brown people who are told and believe they can’t vote because they’re in jail. So the effect is the same.”

Whether the question of inmate voting rights will be settled with a conference or require further legal action, organizers and advocates are determined to not see another election pass without a statewide policy protecting incarcerated voters’ rights under the law.

“Even with the law on our side, we are being disenfranchised by misinformation,” said Nunn. “That is a blow to our communities and to our democracy.”

Jennifer Rae Taylor can be reached at jraetay@gmail.com.

Let my people vote!

by Pastor Kenneth Glasgow

One of the most important rights people lose by going to prison is the right to vote, so voter re-enfranchisement is key to successful reentry back into the community. People who have been in prison are determined to build political power in order to win back our rights, and one expression of political power is exercising our right to vote.

Voting rights laws differ widely from state to state, and 48 out of 50 states have laws that disenfranchise or limit voting rights for people with felony convictions. A national research organization estimates that at least 5.3 million Americans will be denied the right to vote in the 2008 election because of a felony conviction.

A total of 13 percent of Black men are ineligible to vote because of past convictions. Dorsey Nunn, co-founder of All of Us or None, noted: “The voting rights of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and people with past convictions have been violated over the course of decades, at a minimum through benign neglect and at worst deliberate disenfranchisement of hundreds of thousands of people. The lessons coming out of Florida in 2000 were not only a question of hanging chads but the open suppression of Black votes through the manipulation of felony conviction status.”

Formerly incarcerated people throughout the U.S. are determined to unite to make our voices heard: As our forefather Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without demand. It never has and never will.” Join us in a National Day of Action for Jail and Prison Voting Rights.

We’ve gone from the back of the bus to the front of the prison. The struggle continues.

We’re not second class citizens, but second chance citizens, SO LET MY PEOPLE VOTE!

Pastor Kenneth Glasgow is co-convener of the National New Bottom Line Criminal Justice Coalition and the founder and executive director of The Ordinary People Society (TOPS), 403 West Powell St., Dothan AL 36303, (334) 671-2882, www.wearetops.org or www.revkennethglasgow.blogspot.com. This is excerpted from his call for the National Day of Action for Jail and Prison Voting Rights on Aug. 16.