by Junya

“Taken as a whole, the record compels a finding that the prosecutor’s non-race based reasons for peremptorily striking M.C. were pretexts. The fact that the prosecutor peremptorily struck the only other African-American juror in the jury pool and provided at least two implausible reasons for that challenge reinforces this conclusion.”

The court’s method of reasoning was also clearly given: “comparative juror analysis.” If each of a prosecutor’s non-racial reasons for striking a minority juror is clearly and convincingly refuted, because they were not applied to otherwise similar non-minorities who were permitted to serve, then the court must conclude that the actual and only reason for striking the juror was race.

While much mainstream attention goes to racially discriminatory policing – so-called “racial profiling” – and activists have focused on the weakness of current police accountability, the racially discriminatory practices of prosecutors and their near-absolute autonomy have largely slipped under the radar. Yet, while police have wide discretion in making arrests, prosecutors have complete discretion – with no oversight – in deciding if an arrested person is actually charged with a crime.

Consequently, as Angela J. Davis has long argued, to tackle racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system, we must recognize that “one of the most significant contributing factors is the exercise of prosecutorial discretion … Prosecutors traditionally have resisted even modest efforts to reform the way that they perform their duties and responsibilities. Because most prosecutors are elected officials, their constituents must view the issue as a high priority and insist upon prosecutorial action.” [2]

So when a high court rules that one of the state’s respected prosecutors acted with racially discriminatory intent in removing jurors, alarm bells should go off for any Californian who wants to see the state’s criminal justice system become less criminal, and more just.

Both Steve Wagstaffe and Berkeley appellate attorney A.J. Kutchins kindly agreed to discuss the ruling for SF Bay View readers. (Deputy Attorney General Michele Swanson, who represented the state in the appeal, did not return calls seeking comment.) In addition, Golden Gate University Professor of Law Peter Keane, respected legal analyst and former San Francisco chief assistant public defender, provided another perspective on the ruling.

Racial jury rigging goes stealth

Wagstaffe may have lost by his fouls, but from all accounts, including his own, the loss was a stinging smackdown. The feds hit him with a lethal combo. They snatched his victory by reversing a high profile murder conviction (the victim was the daughter of an NFL star) by the high-profile prosecutor (every weekday Wagstaffe emails updates to the press [3]) when he is poised to become the DA. And they smacked him in a most sensitive area – declaring that he rigged the jury by excluding African-American jurors.

Wagstaffe responded to this blow to his “gut feeling”: “This was a disappointment to me. I have to accept it, but I don’t agree. I feel very personally maligned by it. I now have a greater sympathy for people who have been falsely accused. Of course, I don’t compare myself with someone who has been incarcerated. There’s been no loss of liberty.”

In fact, there appears to be no actual loss of anything for Wagstaffe. He remains fully supported, by both the county and state, as a top prosecutor and political candidate, while the press made scant mention of his racially-biased jury rigging. His name was not even mentioned in the LA Times or UPI reports.

Of course, the appellate ruling was not personal – it was about the business of giving California courts a stiff shove into the 21st century.

Kutchins observed, “For the last two decades, California courts have had a shameful history of countenancing racial discrimination in jury selection and have been continually rebuked by the federal courts.”

Keane agrees: “Racial discrimination in jury selection was first prohibited in 1880, yet this state still has not caught up.”

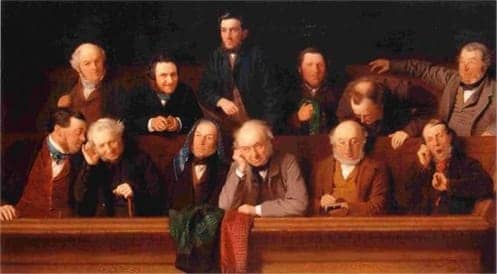

In fact, although the right to a trial by a fair and impartial jury is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the struggle to eliminate racial discrimination in jury selection has looked less like a progressive march forward and more like judicial Whac-A-Mole – bursts of court rulings hammering at new forms of bias that keep popping up.

Bias pops up at the first stage of jury selection, when the pool from which juries are drawn – which is determined by government policy – is not representative of the community. In 1880, the Supreme Court invalidated a West Virginia statute that declared that African-American citizens could not serve as jurors.

Subsequently, discrimination just became more subtle, as laws that explicitly excluded African-Americans were replaced by laws that were used to effectively exclude. For example, a Delaware law required jury members to be “sober and judicious” – a requirement not met by African-Americans, Delaware argued. California currently selects jury panels from Department of Motor Vehicles and voter registration lists – a modern translation of the “sober and judicious” requirement?

In the next stage, the judge and attorneys for the prosecution and defense interview jurors. In theory, their intent is to remove jurors who cannot be impartial in the case to be tried. Attorneys have two ways to exclude jurors during jury selection. A “challenge for cause” requires convincing a judge that a juror cannot be impartial. The more permissive “peremptory challenge” allows attorneys to exclude jurors without explanation – thus providing another hole for bias to pop up.

As a Tufts University study points out: “Peremptory challenges are often based on ‘gut feelings’ and are therefore likely to be colored by observable characteristics of potential jurors; indeed, it is well-documented that attorneys systematically consider categories such as gender, occupation, and nation of origin in their efforts to eliminate jurors they believe to be unfavorable to their clients … despite the sometimes tenuous link between such characteristics and jurors’ verdict tendencies … ” [4]

That triggered another round of Whac-A-Mole, as the judicial hammer came down again. In Batson v. Kentucky (1986) the Supreme Court, recognizing that peremptory use for racial discrimination violated the constitutional right to equal protection, ruled that jurors could not be removed solely on the basis of race. [5]

Kutchins summarized the post-Batson rules: “In the legal field, there is a common saying on juror elimination: ‘You can do it for any reason, or no reason. You just can’t do it for a bad reason.’”

Given the long history of unrestricted use of peremptory challenges to racially scrub the jury panel, the effect of Batson was not difficult to predict: Racial rigging was recast in race-neutral justifications.

The Tufts experiment confirmed this behavior (using gender instead of race): “In Study 1, participants who acted as prosecutors in a jury selection paradigm eliminated female jurors more often than male jurors, but then justified these biased choices by citing gender-neutral information. Troublingly, Study 2 showed that explicit instructions against the use of gender failed to eliminate selection bias, and in fact resulted in even more elaborate justifications.”

Regarding today’s California courts, Kutchins tells us: “It is an everyday practice for prosecutors to eliminate African-Americans in jury cases, simply because they are African-Americans. The Ninth Circuit only publishes a fraction of its opinions. This is the second opinion published in the last year on racial discrimination [the other was an Alameda County case, for which Kutchins was also counsel: Green v. Lamarque] [9].

“For 10 years, with increasing frequency, the federal court has published opinions rebuking the state for failing to rule against racial discrimination in juror selection. The great majority of these cases involve prosecutors eliminating on the basis of race. The court is clearly trying to send a message.

“As a result, prosecutors are getting more sophisticated. This may sound cynical, but prosecutors are just getting more sophisticated about justifying juror elimination. And trial judges – who may be colleagues of the prosecutor – merely rubber-stamp the justifications given.”

Indeed, prosecutors’ juror challenges now can be backed by professional jury consultants, statistics and software [10]. Ye Olde Days of California prosecutors’ unprocessed racism is seen in an appeal of a 1992 conviction, where Deputy District Attorney Worth Dikeman – formerly in Humboldt County, now in El Dorado County – justified striking three Native American women and one Asian woman from the jury, to obtain an all-white jury. No one could accuse Dikeman of sophisticated justifications:

“Ms. Rindels was the one darker skinned female … that I challenged. My experience is that [N]ative Americans who are employed by the tribe are a little more prone to associate themselves with the culture and beliefs of the tribe than they are with the mainstream system, and my experience is that they are sometimes resistive of the criminal justice system generally and somewhat suspicious of the system …

“… [C]hild molesting is okay in certain [N]ative American cultures … and there are a whole bunch of people that violate our laws that are [N]ative Americans and they go much more often through the [N]ative American system than the criminal system … ” [11]

Dikeman saw nothing wrong with his justifications: “It is wrong to systematically exclude groups from the jury pool. I don’t do it. I haven’t done it and I will never do it.” The trial judge accepted the above justifications as non-racial. The California Court of Appeal found “some cause for concern” because “the underlying assumption that Native Americans as a group are ‘anti-establishment’ is itself based on a racial stereotype” yet ultimately concluded that the prosecutor’s other “nonracial” reasons for striking Rindels were genuine.

Both the federal district court and a normal Ninth Circuit review also accepted Dikeman’s stereotyping, before the full Ninth Circuit finally rejected the justifications in 2006, noting, “The racial animus behind the prosecutor’s strikes is clear” – 14 years after the discrimination claim was raised.

Just another whack?

So what’s the significance of this latest whack at racial bias in jury selection? Will it really change jury selection in this state?

Wagstaffe plays it down, laying his hopes on a future reversal of the decision: “We have requested the whole Ninth Circuit panel to review this. We’ve heard no decision yet. If they deny, then the next step will be decided by Mr. Brown [state Attorney General Jerry Brown] and my boss [San Mateo DA Jim Fox] … For California, this establishes a system for evaluating bias in juror selection: comparative juror analysis.”

Wagstaffe’s minimization is not surprising, given that he – like Dikeman – denies that he did anything wrong: “I stand by this: I know in my heart that I did not do what they allege.

“I have practiced and lectured in this office for 32 years on how you cannot do this. But from this I’ve learned to keep detailed and extensive notes, so I will put on record why I selected or dismissed each prospective juror. And this is now being incorporated into ongoing legal training.

“The basic principle is not new. That has been in our training all along. This ruling brings a different approach, requiring prosecutors to carefully track their process.”

Or, as Jack McMahon said in his infamous 1986 training video that teaches prosecutors how to lie to judges and exclude African-Americans from juries: “You’re not going to be able to go back and make something up about why you did it. Write it down, right then and there!” [12] Track your bogus race-neutral justifications carefully.

But Keane sees more clout in this hit: “Very significant. It will have an effect in the local area, where district attorneys in particular have flouted prohibitions against using racial discrimination in jury selection – and (they’re) getting away with it as long as the DA came up with a half-hearted story. This is long past due. Rulings in the past have been more oblique. This was direct – no ifs, ands or buts. It closes cracks in the door.

“You have to sort out what prosecutors say for public consumption. They are political animals – they have to run for public office. So they are unlikely to publicly concede fault in their past and current practices. But they are not impractical. They realize that they run a big risk of reversal of significant cases.

“While they may publicly vow to appeal to the Supreme Court, they must look at their likelihood of success. The number of cases taken by the Supreme Court is shrinking – it’s likely that the Court would not review it. And if they did, it’s likely that they would uphold the Ninth Circuit decision, as it is consistent with past rulings. In the long run, state prosecutors are going to conclude: ‘We have to stop getting away with this stuff.’”

While Kutchins agrees that California prosecutors are unlikely to get relief from the Supreme Court, he has no illusions about the compliance of California courts: “Until a few years ago, California courts were refusing to strictly apply Batson, interpreting it as not requiring comparative juror analysis: ‘All we need to do is decide if his reasons are race-neutral.’ The federal court response was: ‘No, you need to find out if he is discriminating. To do that you need to do comparative juror analysis.’

“[In this ruling] the Ninth Circuit said California courts did not do what they need to do.

“California courts give up just as much as they feel they need to give up. With each decision handed down by the federal courts, California has responded: ‘We have to do X, but we interpret this as we don’t have to do Y.’ California courts can fight it, but the Supreme Court has been good in this area.

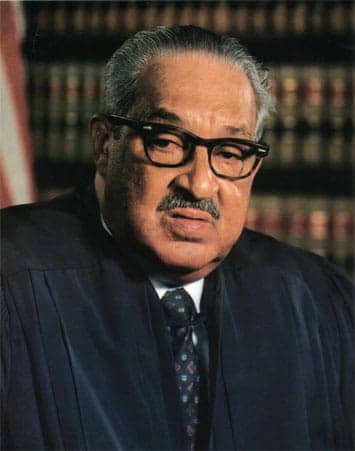

“Ultimately I believe, as Thurgood Marshall wrote, the problem comes down to the peremptory itself.”

That won’t happen in a Wagstaffe world – he declared: “I’m one of those old time dinosaur prosecutors that don’t want to give up peremptory challenges, to keep out stealth jurors.”

This is not the first time Wagstaffe has publicly fretted over his fear of a “stealth juror” – a vague term that an American Bar Association report defines as “a juror with a hidden agenda.” In June 2008 after a judge dismissed a juror, during deliberations in a “gang murder” trial, who was found to have falsely denied her gang affiliation on a jury selection questionnaire, Wagstaffe said: “It is our subjective opinion that she was a stealth juror, that she specifically wanted to be on this jury.” [13]

Then in August 2009, when one of the potential jurors in another case was found to be the defendant’s brother, Wagstaffe again suggested the jury selection process had been rigged by an infiltrator: “What are the odds that the defendant’s brother would be on the jury panel for the defendant’s jury trial? … Can you define the term ‘stealth juror?’” [14]

But Wagstaffe’s “stealth juror” claims lock him into a contradiction. Because while Wagstaffe licks his wounds, the county has shown its support for his racially discriminatory intent by sending him back to craft another jury, for another murder trial – this time going for the death penalty against Alberto Alvarez, 26, accused of killing white East Palo Alto policeman Richard May. And when Alvarez’s attorneys filed a motion to restart the jury selection process, arguing that the jury pool did not include a representative number of African-American jurors, the judge denied the motion, ruling that the process of jury duty call was a random, automated system. [15]

So if Wagstaffe argues that the jury duty call is truly random, then his suggestions of stealth jurors rigging the jury selection process become absurd. Because, by the definition of “random,” the odds that the defendant’s brother would be on the jury panel for the defendant’s jury trial are no less and no more than any other eligible candidate’s odds of being on any jury trial.

In fact, during jury selection in the trial of Alvarez, two jurors revealed that they were long-time acquaintances of Wagstaffe. Another was a friend of May’s mother. All were dismissed. [16]

On the other hand, if Wagstaffe continues to loudly wail that stealth jurors are infiltrating the jury panel, then he is admitting that the system can be rigged by ordinary citizens – which shatters the claim that the system is automatically race-neutral. If it can be rigged by ordinary citizens, then it certainly can be rigged by the county to be racially discriminatory.

Of course, such contradictions need not trouble Wagstaffe. As the judge in Alvarez’ case has shown – when he wasn’t nodding out – Wagstaffe can continue to rely on district and state judges to rubber-stamp his most dubious claims. As history repeatedly shows us, effective change will not come from the grace of the rulers, but from the forces of opposition letting those “old-time dinosaur prosecutors” know that it’s time to pick up their pensions and move on.

The trial of Alberto Alvarez is underway in Courtroom 2K, 400 County Center, Redwood City. Call the Clerk’s Office for the schedule: (650) 363-4711. The case number is SF343269.

References

1. Ali v. Hickman, July 7, 2009, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2009/07/07/07-16731.pdf

2. Angela J. Davis, “Racial Fairness in the Criminal Justice System: The Role of the Prosecutor,” Fall 2007, Columbia Human Rights Law Review, http://www3.law.columbia.edu/hrlr/hrlr_journal/39.1/i.%20Davis-F.pdf

3. The Wagstaffe Chronicles, April 7, 2008, Cal Law blog, http://legalpad.typepad.com/my_weblog/2008/04/the-wagstaffe-c.html

4. “Bias in Jury Selection: Justifying Prohibited Peremptory Challenges,” 2007, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, http://www.people.hbs.edu/mnorton/norton%20sommers%20brauner.pdf

5. Batson v. Kentucky, April 30, 1986, U.S. Supreme Court, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batson_v._Kentucky

6. J. E. B. v. Alabama, April 19, 1994, U.S. Supreme Court, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.E.B._v._Alabama_ex_rel._T.B.

7. Taylor v. Louisiana, Jan. 21, 1975, U.S. Supreme Court, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.E.B._v._Alabama_ex_rel._T.B.

8. Campbell v. Louisiana, April 21, 1998, U.S. Supreme Court, http://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1997/1997_96_1584

9. Green v. Lamarque, Aug. 4, 2008, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2008/08/04/0616254.pdf

10. “Jury-Rigging: Can a computer pick a better jury than a high-priced consultant?” Aug. 10, 2006, Slate, http://www.slate.com/id/2147351

11. Kesser v. Cambra, Sept. 11, 2006, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2006/09/11/0215475.pdf

12. “Former Philadelphia Prosecutor Accused of Racial Bias,” April 3, 1997, NY Times, http://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/03/us/former-philadelphia-prosecutor-accused-of-racial-bias.html

“Jury Selection, with Jack McMahon,” 1986, Office of Philadelphia District Attorney

- excerpts: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qYxVZ8RGTn8

- unedited: http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-5102834972975877286

13. “Juror booted from murder trial,” June 20, 2008, San Mateo Daily Journal, http://www.smdailyjournal.com/article_preview.php?type=lnews&id=93764

14. “Am I my brother’s juror?” Aug. 28, 2009, San Francisco Chronicle, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/blogs/crime/detail?blogid=144&entry_id=46418

15. “Attorneys to question 240 prospective jurors in Officer May murder case,” Sept. 7, 2009, Palo Alto Daily News, http://www.mercurynews.com/peninsula/ci_13288862

16. “16 jurors screened in Officer May murder trial,” Sept. 8, 2009, Palo Alto Daily News, http://www.mercurynews.com/peninsula/ci_13296794

Junya, a Bay Area writer who analyzes the role of race in the criminal justice system, can be reached at junya@idiom.com.