by Zachary Norris

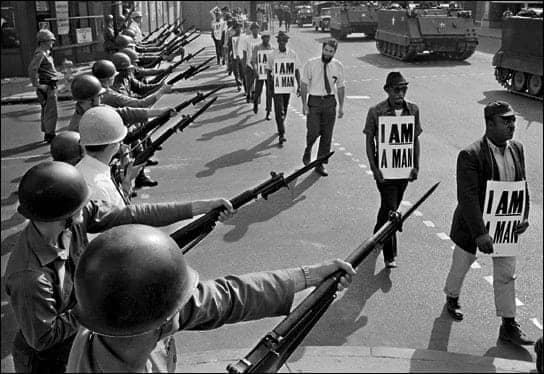

King was jailed numerous times as a civil rights leader. Speaking on the need for solidarity for those arrested in acts of civil disobedience, he once said, “When they put me in jail, let ‘em know that they got a hundred more to put in jail, … let ‘em know that they got another thousand to put in jail, … let ‘em know that they got ten thousand more to put to jail.” Looking back, it seems the number of Black people in prisons grew just that fast. There are now a million Black people incarcerated in the U.S., a half-million Latinos, and millions more are in jail or on parole.

Perhaps not even the visionary King could have foreseen the capacity of the U.S. criminal justice system to turn people of color into convicts. Within poor Black and Latino communities, it has become normal to go to jail, not as an act of defiance but as an unfortunate rite of passage. Pressing the necessity of a “Poor People’s Campaign,” King called for great solidarity among people of color across class lines.

Theoretically, many people of color are still hung up on a failed “politics of respectability” that King himself abandoned. The principal tenet of the “politics of respectability” is that, freed of racial discrimination, people of color can meet the moral standards of white middle-class Americans.

During the early movement to end the first Jim Crow, many campaigns based on a “politics of respectability” were successful. On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a seasoned NAACP organizer, who King called “one of the finest citizens in our community,” sat down in the “whites-only” section of a segregated bus and helped ignite the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Since the late ‘60s, the political right’s labeling poor persons of color as “welfare queens,” “criminal,” “terrorist” and/or “illegal” and undeserving of social investment facilitated the rollback of social spending and the ramp-up of the criminal justice apparatus. The subtext of the politics of respectability has been, “We are not welfare queens, criminals, illegal aliens and/or terrorists,” which contributes to the predominant political framework by allowing for continued discrimination through criminal justice systems.

Dr. King’s dream was NOT having prison guards of color obtain equal opportunity to watch their incarcerated cousins. All people who care about equality and justice must join renewed “poor people’s campaigns” across the nation and adopt a “politics of family” that is inclusive of the Claudette Colvins and the Rosa Parks and our kinfolk who have run afoul of the law.

The seeds of this movement are bearing fruit across the country. In Los Angeles, students and parents successfully challenged the $250 truancy tickets given to late students. In Louisiana, families closed a youth prison and almost turned it into a community college. Formerly incarcerated people “banned the box” by removing the question on public job applications asking if a person has a criminal record.

Many of the local organizations leading these campaigns are forming national networks such as Dignity in Schools, Critical Resistance, All of Us or None and Justice for Families. Until this campaign to end the new Jim Crow is successful, let there be, as Dr. King said, “no rest, no tranquility in this country until the nation comes to terms with our problems.”

Zachary Norris is the coordinator of Justice for Families (J4F), a new national support, advocacy and organizing initiative of families of incarcerated and court-involved youth. J4F works to challenge the community disinvestment, “zero tolerance” school policies and punitive laws that lead to the disparate lockup of youth of color by promoting justice reinvestment: the reallocation of government dollars wasted on ineffective and harmful juvenile justice policies in systems of support for youth and families. To contact J4F, write to Zachary Norris, Esq., Coordinator, Justice for Families, 175 Remsen St., 8th Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201; call (347) 505-6657; email zachary.norris@gmail.com; or visit www.justice4families.org.