by Jean Damu

The importance of discussing this apparent cultural collision is that within the U.S. immigration movement, leaders often do not clearly understand racism as it impacts upon immigration legislation on local and national levels, nor do they seem to clearly understand why, generally speaking, African Americans tend to be their most reliable allies.

Also, moves by President Obama to re-ignite the discussion to reform U.S. immigration policies and Dr. Henry Louis Gates’ PBS documentary series, “Black in Latin America,” have brought the issue into current public focus.

Another reason for developing this discussion is that within the U.S., there appears to be a growing movement to encourage people of mixed race ancestry – as many Black Latinos are – to define themselves as non-Black, which will ultimately serve to help render Blacks as increasingly invisible, further marginalizing them.

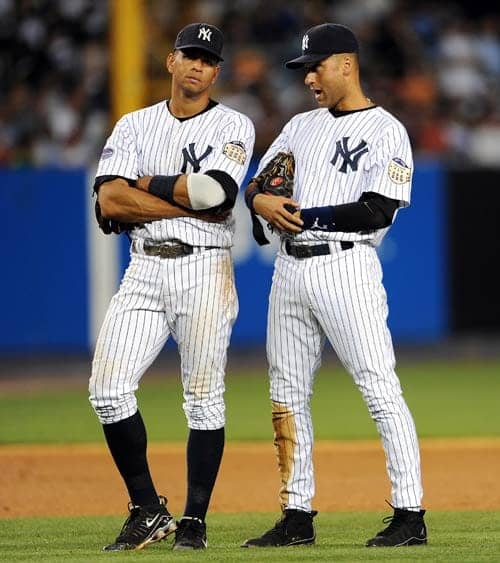

As a popular illustration of this racial dichotomy, consider the left side of the New York Yankees infield – third baseman Alex Rodriguez and shortstop Derek Jeter. They could be twins, but one is considered Latino while the other, Jeter, is an African American.

So perhaps the question is, how is it in the U.S. that race is the all important factor while in the “Latino” states, and for purposes of this discussion we are referring to the Spanish and Portuguese speaking states, race seems to take a back seat to class?

Within the U.S., there appears to be a growing movement to encourage people of mixed race ancestry – as many Black Latinos are – to define themselves as non-Black, which will ultimately serve to help render Blacks as increasingly invisible, further marginalizing them.

In order to understand this apparent cultural confusion, it is necessary to trailblaze our way backwards in time to the beginnings of European colonization and the creation of slavery in the West.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, when Portugal and later Spain became involved in colonizing the Western Hemisphere, the common people in those states were still legally and physically tied to the land. In other words, common people were required to work the land for subsistence and pay the surplus product they produced – whether agricultural produce or money – to the landowner class, whether that class was the church or individual men of wealth.

Those conditions meant that the masses of common people were tillers of the soil and, by and large, had not developed small business and craft skills.

When the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns sent forward colonizing expeditions to the “New World,” these expeditions were mostly comprised of soldiers and clerics, not the most suitable professions for building new societies.

Furthermore, Spain was quite lucky. The Spaniards found gold and silver soon after they debarked on American soil, further retarding colonial development because in the early stages soldiers were amply used to round up the Indians to force them to provide gold and silver.

Very few women ventured forth from Spain and Portugal to the colonies in the West. When efforts were put into motion to establish colonies, the Spanish and Portuguese colonists cohabited with the enslaved Indian and African women and it was from these pairings that resulted the mixed race populations that exist in the former Spanish and Portuguese colonies today.

There are other factors that influenced this process, such as Spain and Portugal’s proximity to Africa and the Moors’ occupation of Spain, but I argue that the economics of women’s social relationships were dominant.

We will return to this dynamic shortly.

The Spanish and Portuguese colonists cohabited with the enslaved Indian and African women and it was from these pairings that resulted the mixed race populations that exist in the former Spanish and Portuguese colonies today.

In England, however, economic and social conditions at the beginning of the colonizing era couldn’t have been more different.

The common people had been pushed off the land to make way for the cattle herding, dairy and sheep herding industries, then forced into villages and cities where craft and business skills were developed out of the necessity to survive. Women were as much involved in this process as men. In fact, evidence of this still exists in the English language.

For instance, before the word spinster evolved to signify a woman of indeterminate age, a spinster was a woman who was employed in the spinning industry – spinning cotton or wool into thread or yarn – while men who were employed in that industry were spinners.

Similarly, while webbers were men employed as weavers, websters were women so employed. Brewers, of course, were men who brewed alcoholic beverages from grains and cereals, while brewsters were women employed in the brewing industry.

From Charles and Mary Beard’s early 20th century classic study, “The Rise of American Civilization,” we are informed that early English censuses indicate that women in various English localities were employed as butchers and bakers – although no mention is made of candlestick makers. Furthermore, the Beards say, two women – Katherine West and Millicent Ramsdent – were original investors in the London Company, created to develop Virginia.

This is not to suggest women enjoyed civil rights, but these brief examples of women’s participation in England’s economy, as it began what was likely its transition from feudalism to capitalism, are provided to demonstrate why women were intimately involved in the British North American colonizing process. Because of their skills and knowledge, men who brought a woman with them to North America were given additional land. When entire families migrated to the West, additional land was provided for each additional family member. Therefore an economic incentive existed to involve women in the colonizing process.

These conditions, however, raise an interesting question that bears directly on our discussion.

We have already seen how difficult it was for the so-called Latin colonies to attract skilled and unskilled workers. The dearth of European workers was one reason why the colonials felt it necessary to enslave Indians and then Africans to perform first extractive labor followed later by commodity agricultural labor.

In fact, Brazil and several of her neighbors were still attempting to recruit European immigrants well into the 20th century, which is one reason why so many Nazi fugitives wound up there following the destruction of the Third Reich.

But we are well within our rights to ask why – if England primarily, and later other European countries, was contributing masses of skilled and unskilled workers and craftsmen and women – was it necessary to develop slavery in North American British colonies?

Keeping in mind that this is merely an essay and not a book, we can say the answer is basically just two words: free land.

We already know that slavery in what became the U.S. did not just appear as a full blown import from the Caribbean or South America and that the first Africans brought to British North American colonies were purchased as indentured servants, the same condition by which many Europeans came.

However, what was discovered in the case of the indentured servants, Europeans and Africans, was that once their contracts were fulfilled and once the aboriginal inhabitants had either been removed or “neutralized,” they could simply venture westward and claim from speculators a cheap purchase price for their own land.

This process worked adequately in the Northern colonies where commodity crops such as onions, corn and other grains could be grown profitably in units that could be managed by a single family or with just a few wage laborers.

In the Southern colonies this was not the case at all. There, the primary commodity crops of tobacco, rice, sugar and later cotton were all labor-intensive crops that required large numbers of workers to constantly care for the product. The wages that plantation owners would have had to pay in order to keep formerly indentured servants on the land – to dissuade them from obtaining their own land – were prohibitive. For this reason, laws were gradually instituted to chain Africans to the plantation system, which ultimately meant that, in broad terms, Africans as a people were enslaved in the British North American colonies.

The economic motivations that led to the development of slavery in North America are not different from the economic motivations that encourage employers in the U.S. to hire undocumented immigrants today. The logic of this can easily be understood by anyone who has on occasion needed some extra work done around the house and, rather than call the laborers union to hire a union member, or even a relative, has simply driven to the nearest local interchange and “hired a Mexican” for, at the very most, half the cost of a documented worker or union member.

Despite the development of slavery in North America, the presence of an almost equal number of European women as European men meant that there was no economic or social motivation, as there was in the Latin colonies, for European men to cohabitate with Indian or African women. In fact, from the earliest of times in the colonies, legal barriers were constructed to prevent the intermingling of races, primarily as a means of preventing labor unrest that would threaten the security of the incipient land owning classes.

Over a relatively brief period of time, racial divisions became very pronounced. Because the British colonial communities were whole communities and because they contained almost equal numbers of men and women, which resulted in miscegenation being declared illegal, a very strict and narrow definition of whiteness to describe landowners was created. A definition so strict in its narrowness that when Irish and Italian immigrants began to arrive, neither was originally considered to be white.

There was no economic or social motivation, as there was in the Latin colonies, for European men to cohabitate with Indian or African women.

Thus came to be formulated the American variant of the “One Drop” theory that hyperbolically reasoned anyone with one drop of African blood was deemed to be Black.

Meanwhile – most notably in Brazil, but in the other Latin colonies as well – the exact opposite came into being.

We have already noted how Spain and Portugal were unable or unwilling, with possession of little economic incentive, to send large numbers of women to their colonies and how this led to widespread coupling of the European colonists with the Indigenous and African people.

In 1817 – a British traveler to Brazil, Henry Koster – recorded these observations:

“Marriages between white men and women of color are by no means rare [though often commented upon – ed.]. Indeed, the remark is only made if the person is a planter of any importance and the woman is decidedly of dark color, for even a considerable tinge will pass for white. If the white man belongs to the lower orders, the woman is not accounted as being unequal to him in rank, unless she is nearly black.”

In these cases, where a European property owner wanted to actually marry an Indian or African, they usually applied to the Spanish authorities in Spain to have a Certificate of Whiteness issued declaring their partner officially to be white.

This is as clear a description as one is likely to find of the Latin One Drop theory – namely that anyone with one drop of European blood is deemed white – the polar opposite of the American One Drop theory. But both variants, American and Latin, worked to keep Blacks at the bottom of the social and economic spectrums.

It should be noted that each Latin state, due to its own historical and geographical differences, has its own variant of the Latin One Drop rule. None is exactly the same as another, but in almost all cases there was (is) a general recognition that racism was (is) a negligible factor. In fact in Brazil, throughout much of the 20th century, an entire philosophical system known as lusotropicalism (colorblindness) was created to convince Brazilians and the world that Brazil was free of racism.

How have these polar opposite takes on race in the U.S., and other former British colonies in the Western Hemisphere, and the Latin states impacted the thinking and racial consciousness of the various populations?

Both One Drop variants, American and Latin, worked to keep Blacks at the bottom of the social and economic spectrums.

To address this question we must ask another.

Why, even though racial discrimination is universal throughout the Western Hemisphere, is there a high degree of racial consciousness in the U.S. when there is what the former University of California researcher and lecturer Ted Vincent refers to as “racial amnesia” in the Latin states?

In order to make sense of this, we must now turn our attention to the other determinate factor in this discussion, other than the role of women, namely: culture.

We have already seen why it was necessary to develop slavery in the U.S., but if there had not been slavery and only an insignificant number of Africans had arrived here, then it would not have been necessary for Europeans to become white. Europeans, and others, would likely have continued to discriminate on the same basis they discriminated in Europe, and the Irish and Italians to this day would occupy the lower classes.

But slavery was necessary, and in order to promote and protect slavery and land-owning privileges, European solidarity took the form of becoming white.

However, in order to become white, it was necessary for the various European nationalities – especially after Europeans other than the English began to immigrate to the British colonies – to abandon significant aspects of the European cultures and adopt significant aspects of African culture, or at least the culture they came into contact with in the enslaved Africans.

There is a mountain of evidence to support this thesis which lies largely unexcavated. But just for the purposes of this brief essay, simply consider that our national opera, symphony and ballet companies exist largely for the pleasure of society’s elites while the nation’s working people largely embrace, particularly in the field of music, culture that is historically influenced by African Americans.

For the enslaved Africans in the early history of the British colonies, the situation was reversed from that of the Europeans. In order to survive as a people and in the interest of racial solidarity, Africans were forced, often by the use of violence, to abandon their African cultures and create new cultures based of course on their African memories.

For this reason, only in relatively small pockets of the U.S., such as the Gullah-GeeChee Nation of South Carolina and Georgia and other portions of the “Deep South,” do remnants of African culture as it existed when Africans first arrived still survive.

The experiences of Fisk University’s Jubilee Singers are illustrative of Blacks creating their new culture. When the Fisk students sang white oriented hymns, the mostly white audiences went to sleep. But when they sang hymns in the Black style, the group’s popularity soared.

Africans were forced, often by the use of violence, to abandon their African cultures and create new cultures based of course on their African memories.

Seen in this light, the strange and curious phenomena of white folks painting themselves Black and performing songs and dances originally inspired by enslaved Africans, but which soon became gross caricatures, that became wildly popular in the 19th century and remained socially acceptable at least until the middle of the 20th century, is a profound demonstration of how White America reinforced its sense of whiteness by imitating Black America.

Even those Whites too sophisticated to paint themselves Black copied Black styles and raked in fortunes. Benny Goodman, Bing Crosby, Janice Joplin and Michael Bolden are typical examples. This practice continues to this day, which is why many white popular singers attempt to sound Black, but almost no popular Black singers attempt to sound white. Just one episode of American Idol will provide evidence in support of this observation.

Turn the mirror over to examine the Latin states and once again the conditions are just the opposite.

The expanded definition of whiteness and the very narrow definition of Blackness, which we discussed earlier, implies that neither Europeans, Africans nor the Indigenous would need to abandon their cultures in order to conform to the new racial definitions. This seems like a conundrum, but really is not.

The very broad definition of whiteness precluded the need for European settlers to abandon their European cultures to become White. And by extension there was no need for the Blacks to abandon their African cultures to become Black, unless they were those African descendants who were able, because of their color, to move upward into relative whiteness.

Professor Vincent buttresses this theory when he argues that of all the Latin states, only Mexico has developed a national culture. All other Latin states have folk cultures, typified by numerous folkloric organizations, where European, African and Indigenous cultural forms exist side by side.

Of course, to a degree, this is true in every country and certainly in the U.S. But what you don’t see in the Latin countries that you see in the U.S. is the degree to which Black cultural forms, especially music and language, have been adopted by masses of the population.

On the other hand, what you don’t see in the U.S. that you see in most Latin countries are forms of African culture that are nearly as pure in form as when they arrived from Africa.

We should of course qualify here that in places like Brazil and Cuba, where African culture is so visible, it is believed that enslaved Africans were being introduced well into the late 19th century and possibly as late as the early 20th century.

It is well known for instance that in Cuba, hundreds of songs and poems are still recited in an orthodox form of Yoruba that hasn’t been spoken in Nigeria in more than a hundred and fifty years. In fact, researchers from Africa often travel to Cuba and Brazil to study early forms of their own cultures.

What you don’t see in the U.S. that you see in most Latin countries are forms of African culture that are nearly as pure in form as when they arrived from Africa.

However, despite all of that, a high degree of racial consciousness, such as exists in the U.S. and the other former British colonies, never developed in Latin America. Even today in the U.S., where Hispanic and Latino Heritage Month is annually observed, rarely if ever is there an acknowledgement of Africa and African contributions to Latino culture.

But slowly conditions are changing and gradual understanding is emerging.

Jean Damu is the former western regional representative for N’COBRA, National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, and a former member of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who taught Black Studies at the University of New Mexico, has traveled and written extensively in Cuba and Africa and currently serves as a member of the Steering Committee of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration. Email him at jdamu2@yahoo.com.