Rwanda’s economy is said to be doing well, so how does population size become a problem that requires dire, questionable voluntary vasectomies of the poor?

by Charles Kambanda, PhD

At issue is not whether the country needs sound family planning policy. Whether the political elite will stick to voluntary vasectomies is the main concern. Conceptualizing “voluntary” vasectomies in Rwanda’s contemporary public policy, history gloss and politics is utterly crucial.

The timing of sterilizing 700,000 males raises red flags. In Rwanda’s socio-political environment that swivels on passivity, apathy, suspicion and docile citizenry with militarized “civil society,” securing free will of the men to be sterilized borders on insanity.

Who are the poor?

The deprived are the Twa, a secluded ethnic group. The needy are the Hutu peasants who survived the Congo refugee camps’ massacres. The hard-up in Rwandan society are those few Tutsi survivors of genocide who have not benefited from the genocide survivors’ fund. The underprivileged are the Hutu populace that was uprooted from their land, without compensation, under the habitant and land reform government policy.

The poor are those Tutsi returnees who have no close relations in the Tutsi dominated government. The bitter fact is that poverty in Rwanda runs along the country’s ethnic divides. The poor are mostly victims of the country’s unresolved ethnic and power sharing crisis.

History is seldom a bad teacher. However, people are hardly good students of history. Rwanda’s post-independence history, not different from the country’s pre-independence era, insinuates a constant fight between the Hutu, the majority ethnic group making up about 86 percent of the population, and the Tutsi, the minority ethnic group making up about 14 percent. The Twa hardly make up 1 percent.

Growing or dropping in numbers of either ethnic group is an issue for each ethnic group’s political and physical survival. The Hutu-Tutsi co-existence failed on a win-win modus operandi. The victor seeks to depopulate the loser, or at least to delay the other ethnic group’s violent return to power.

War crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide have long been a “social engineering” and depopulation strategy geared at incapacitating the loser in the country’s power grabbing paradigm. In 1959 it was some Hutu’s turn to “depopulate” the Tutsi.

In the 1980s a Hutu-led government flocked the Tutsi to cannibals and crocodiles in the country’s national park, Akagera. Although scholars disagree on whether the 1994 genocide was committed by only the Hutu against the Tutsi, the scholars appear to concur that genocide was a strategy to “tame” the enemy’s unmanageable and unwanted population.

The brutal massacres of the Hutu refugees in Congo, which the United Nations’ Mapping Report accuses the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan troops of, could also be viewed from this perspective. With growing international enforcement of laws on war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, Rwandan society appears vulnerable to apparent legal methods of birth control like “voluntary” vasectomies to achieve the traditional ethnic depopulation conspiracy.

Sociologists, philosophers and psychologists have long discussed whether a poor person can make choices. Do the poor have free will? The Rwandan government does not appear uptight about this paradox. The poor, who cannot nourish their children, are said to be going for “voluntary” vasectomies. This is the proverbial hiding of the head in the sand.

If poverty is a criterion for vasectomies, free will cannot exist

Public policy analysts consent that current latent public policy ideas and motives of any country must be read in light of the similar previous policy. First, the government of Rwanda implemented the habitant and land reform policy. People were supposed to abandon their traditional homestead and go to live in settlement centers – imidugudu. The previous homesteads were meant to be for farming. Initially the government called it a voluntary policy.

Implementation of this policy turned out to be forceful and inhumane. Some government officials snatched victory from the jaws of defeat; they grabbed the land people had abandoned for settlement centers. Second, the government’s policy of what was called voluntary sharing of land between the Hutu owners and the Tutsi returnees ended in the forceful grabbing of land from the Hutu in many regions of the country. Will vasectomies of the unprivileged males be voluntary as the government suggests?

Self-propagation is a basic need and right. However, producing excessive children, as many Rwandans do, is a symptom of insecurity and poverty. There is a general demographic pattern for the well-off to produce between one to three children. The deprived generally produce more than six children. It is no surprise that in a country like Rwanda, where about 75 percent of the population survives on less that $1 a day, the population is increasing by 3 percent per annum. If quantity of the population be the problem, vasectomies are not a durable solution.

The first beneficiary of development is the human person

The quality of a country’s human resources and not the quantity is what matters. Investing in human development is the only sustainable solution. The Rwandan government has sustained one of the most expensive wars in Africa. It is well documented that Rwanda has one of the biggest and most heavily armed militaries in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Rwanda runs the most expensive presidential personal security unit in Africa.

Rwanda’s economy is said to be doing well. Ironically, money is available. How does quantity of the population become a problem that requires dire, questionable voluntary vasectomies?

Human history demonstrates habitual failure by some leaders to reconcile the existence of the poor in an environment that the political leadership project as prosperous. Adolf Hitler exterminated the gypsies alongside the Jews because the gypsies – the poor – would negate the economic prosperity of Germany. This is how seriously the world takes protection of the poor.

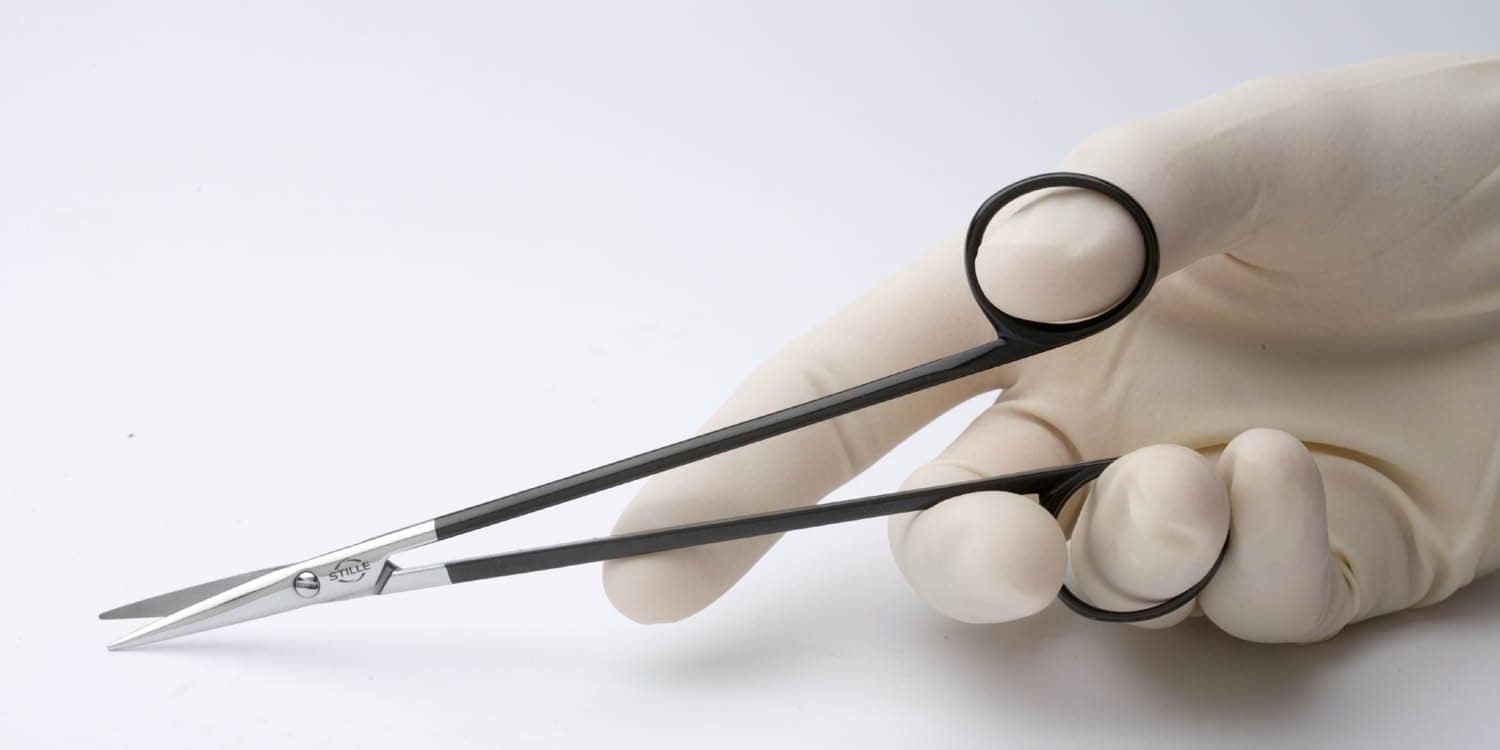

Crime against humanity

Vasectomy in this unique Rwandan context might amount to a crime against humanity. The essence and function of government is redistributing resources and power among the citizens. Vasectomy in a Rwandan context manifests government failure to perform its core functions and responsibilities. The policy mirrors incivility, lack of public conscience and negates the basic ethical tenets.

Dr. Charles Kambanda, Dip.Phil., BA, LLB, MA ETPM, MBA, MA HRTs, LLM, PhD, teaches at St. John’s University Law School, LLM Center, New York, and previously lectured at the National University of Rwanda, where, according to the Rwanda News Service, he was known for his “outspoken nature.” This story first appeared on The Proxy Lake: Views and News on the African Great Lakes Region.