by Orissa Arend

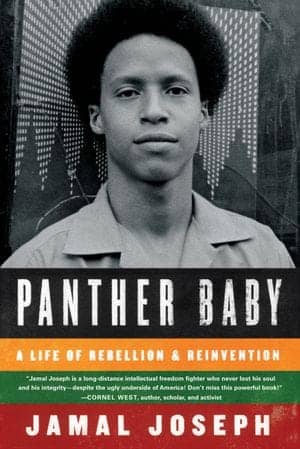

Jamal Joseph’s “Panther Baby: A Life of Rebellion and Reinvention” is a story of love, revolution, rage and redemption. Joseph’s brilliant, honest, insightful narrative of his coming of age in New York City in the late 1960s at the height of the Black Power movement is so riveting that I had a hard time putting it down, even to sleep. And when I did, it invaded my dreams.

Jamal Joseph’s “Panther Baby: A Life of Rebellion and Reinvention” is a story of love, revolution, rage and redemption. Joseph’s brilliant, honest, insightful narrative of his coming of age in New York City in the late 1960s at the height of the Black Power movement is so riveting that I had a hard time putting it down, even to sleep. And when I did, it invaded my dreams.

Beginnings

Jamal was conceived in Cuba. His father, unaware of his mother’s pregnancy, had disappeared to fight alongside Che and Fidel in the revolution. Jamal’s beautiful debutante mom was sent by her parents to live with an aunt in New York City. Arriving in New York in 1952, she was just an unwed Black Latina teenager who couldn’t speak English. She put her child in foster care. When he was four, Jamal was adopted by “Noonie” and Charles Baltimore, a couple in their 60s who he considered his grandparents. They had been part of Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa Movement, and they had no love for white people.

The first few chapters of Joseph’s book are endearing with boyhood remembrances of adoptive grandparents, relatives in the country, first encounters with girls, tough lessons about race, being teased, learning to fight – things anybody who can remember being a kid can relate to.

His decision to become a Black militant and to search for the Black Panther office shortly thereafter was funny and naïve and rife with adolescent assumptions. Instead of guns, the Panthers handed him books. “I went to the Panther office saying I hated ‘Whitey’ and I came out talking about Marx, Lenin, Mao and Che Guevara. This was new, exciting and really confusing. I had grown up learning to fear, distrust and yet admire white people. At the same time, I had learned to be self-conscious and sometimes hateful toward my Blackness. Now I had to rethink everything.”

For this straight A, college-bound apple of his devout Christian grandmother’s eye, hanging with the Panthers at age 15 was heady stuff. There were poor people to organize, lives to save, children to feed. Panthers Yedwa and Afeni Shakur took on Jamal’s parenting when he rebelled against his grandmother – made sure he kept his grades up, respected Noonie, and knew how to assemble and take apart a gun blindfolded. “Being a Panther is about serving the people, mind, body and soul,” Afeni would teach in political education class. “If you’re here because you hate the oppressor and you don’t have a deep love for the people, then you are a flawed revolutionary.”

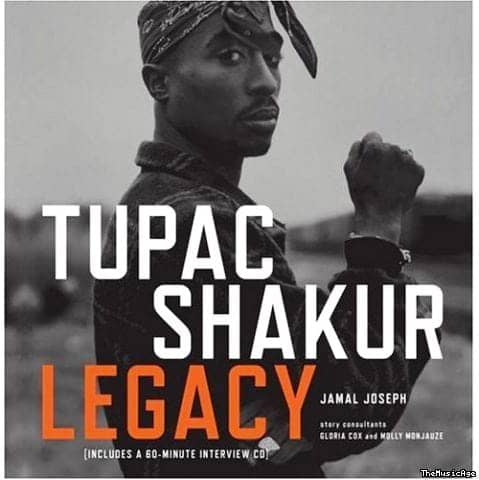

There were guns in the Panther office, but they were in a drawer or a closet. These revolutionaries believed that if the masses were organized and unified enough, armed struggle might not even be necessary. Later on, things would get complicated. Yedwa would turn out to be an agent provocateur. Afeni would give birth to Tupac, who would rap about gangsta life and be gunned down in a drive-by shooting. Panthers in jail would turn on those who were out, East Coast vied against West Coast and there were splits within the highest ranks.

“Being a Panther is about serving the people, mind, body and soul,” Afeni would teach in political education class. “If you’re here because you hate the oppressor and you don’t have a deep love for the people, then you are a flawed revolutionary.”

But that all lay ahead. Jamal was a good speaker and a quick study. After he learned to treat Panther sisters with respect (instead of “What’s happening, baby?” “The revolution is happening, brother, and I’m nobody’s baby.”), it was pretty much revolutionary heaven for Jamal.

Prison

I see many parallels between the Panther experience in New York and New Orleans. In New Orleans, we too had a young one who was determined to fight alongside the older Panthers and who got swept up when they were arrested. That’s what happened to Jamal. Cops broke into his grandmother’s home in the middle of the night and carted him away.

He and 20 other Panthers became the New York 21. Here, our young Panther Bo ended up in a jail for youth that was more like camp in the country, thank God, whereas Jamal was locked up for 11 months at the infamous prison on Riker’s Island. At this point, both youngsters were eager to share the fate of their older comrades.

Just as I couldn’t bear to hear New Orleans Panthers Malik Rahim and Robert King’s stories of day-to-day prison life in Orleans Parish Prison and Angola State Penitentiary, I didn’t want to read Chapter 6 of “Panther Baby,” “To the Belly of the Beast,” or Chapter7, “Walk Slow and Drink Plenty of Cold Water,” or Chapter 8, “When Prison Doors Open, Dragons Fly Out.”

But what I learned from these stories is that even in the cruelest, most violent and oppressive settings, young Black men could confront racist structures and could improvise. Jamal used the cell toilet as a refrigerator; Robert King cooked candy in solitary confinement. They could organize other inmates despite the Draconian strategies of the guards to divide them.

They could hold classes, establish a code of behavior, and share extremely scarce pooled resources. It was the 10-point program of the Black Panther Party and the solidarity of their revolutionary purpose that made this possible, Panthers told me. As Joseph puts it, “If prison was a university, as Malcolm said, then our Panther wing was grad school.”

Over the months Jamal learned to endure being a “political prisoner in a concentration camp. … My only regret was that I had never done more than French kiss a girl as we slow danced at a party. I was 16 years old, facing 368 years in prison, and still a virgin.”

Life on the edge

He got out, though, and for a while lived the difficult and exciting life of a full-time Panther in Harlem. Joseph offers an intriguing explanation of living near the thin edge of death. What I at first assumed was a death wish was really something else.

The New York 21, like the New Orleans 12, arrested after the Piety Street shootout, were all miraculously acquitted after long public trials, outbursts in the courtrooms and huge publicity. Their lawyers were brilliant and knew exactly how to work with and for the Panthers.

But the FBI continued to wage war against the Panthers. As a high-profile fugitive, Jamal decided to go underground. He almost left the country, but in the end couldn’t dessert his comrades. “I would be a punk if I ran for safety while leaving everybody else behind … I want to roll back down to Harlem and fight.”

Things got worse. Drugs were pandemic. “Drugs are genocide!” the Panthers would yell to the junkies and dealers. And then they would rip open the dope bags and dump the contents into the sewer.

Jamal went to college, bought a gypsy cab, married Joyce, a beautiful woman who was a successful actress, model and dancer, had a son, opened a small karate dojo and made a huge impact on students who adored him. One of them, an 11-year-old blond cherub named Angel, was killed in crossfire between rival drug gangs as he stepped out of the dojo. Traumas like this accumulated and began taking their toll.

Fighting the FBI and the drug dealers proved too much even for Jamal. He was arrested for robbing a drug dealer. At 29 he was back in prison for another 12 years. This time he didn’t try to organize. What he did was put on a play that he wrote called “Parole by Death.” It had to be rewritten several times to include white and Native American inmates and various musicians.

There were major obstacles: “My actors were some of the baddest dudes in the penitentiary. They had robbed banks; killed people; shot it out with FBI agents; and stared down knife blades, gun barrels and, in one case, a tank. But stage fright was kicking their asses.”

He worked on graduate degrees, but he almost lost everything when he thought he had to kill an inmate who was out to get him. “Don’t do this.” a voice whispered in his ear, just as he was about to take his plot to fruition. It was his mother, Gladys. She had died when he was 10.

Finally out of prison for good, at times Jamal would feel like a panther in a cage. At those times, his wife Joyce would grab a pen and paper and command him to write. He is now chair of Columbia University’s School of the Arts film division. All of his children are in college. As a young Panther, he once vowed to burn Columbia down or die trying. The university and the Panther Baby both survived and the world is so much the better for it.

Orissa Arend is the author of “Showdown in Desire: The Black Panthers Take a Stand in New Orleans.” She can be reached at arendsaxer@bellsouth.net. “Panther Baby” was published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill in February 2012.