According to Mutope Duguma (James Crawford) at Pelican Bay, it’s his political views “that got me placed in solitary confinement and labeled a BGF member, which I am not; but in order to place you in solitary confinement, IGI/ISU/OCS have to label you a BGF if you’re a New Afrikan.”

He has been in solitary for over a decade. “My cell has a concrete slab bed, the cell is white with a concrete brick slab for TV holding, toilet and sink connected all in one and the steel front panel door and a white painted wall in front. No trees. No animals. No sun. No life. Just prisoners isolated from the world,” he writes.

Life for men in the SHU is bleak, reports Duguma: “I get up at 5:30 a.m., go to the yard when my rotation comes around for 90 minutes, then I am back in my cell for the rest of the day.”

Inmates labeled BGF are routinely validated on the basis of their political views. In a June 2012 ruling, the California Court of Appeals found that Duguma’s political writings were wrongly used to prevent outgoing mail to the San Francisco Bay View newspaper. Duguma referred to himself as a “New Afrikan Nationalist Revolutionary Man.”

A correctional officer intercepted the letter and sent a “Stopped Mail Notification,” indicating that the letter “promotes gang activity” and that his writings were a reference to “ideology created by the Black Guerilla Family.”

Inmates labeled BGF are routinely validated on the basis of their political views.

Stanford Professor James Campbell, after reading the letter, told the court that Duguma is “a serious political thinker, using terms such as ‘New Afrikan’ and ‘New Afrikan Nationalist Revolutionary Man’ that were ubiquitous in Black urban life in the 1960s and 1970s.”

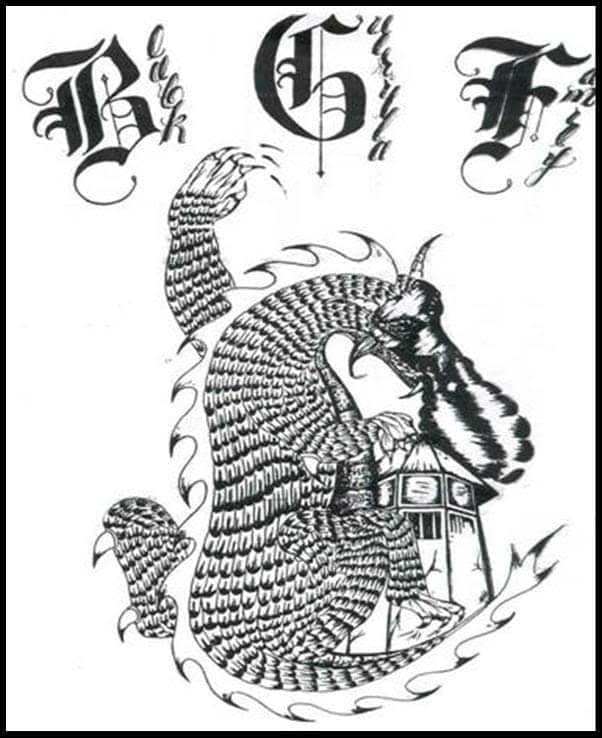

According to accounts by men in California’s SHUs, drawings are also used to justify the continued isolation of inmates. One common image that is used to validate inmates is any drawing of a dragon. For the BGF, one of their symbols is a dragon squeezing a prison guard tower.

According to J., an inmate at Corcoran State Prison: “A K-9 unit was allowed into our cells and spilled some coffee on a Japanese cultural piece I’m doing for an auction to aid the Japanese Tsunami Relief Fund which depicts the sun goddess Amazerasu releasing a phoenix into the sky at sunrise over the Sea of Japan wearing a kimono with imperial dragons on it and a crown featuring the Japanese imperial crest (dragon and phoenix).

“When I filed to have IGI/ISU compensate me for the piece, after reviewing the work, it was returned to me and I was told that if I attempted to mail it out it would be confiscated because ‘it has dragons on the kimono and you’re BGF.’

According to accounts by men in California’s SHUs, drawings are also used to justify the continued isolation of inmates. One common image that is used to validate inmates is any drawing of a dragon.

“I asked, ‘Are you saying the Japanese imperial family is BGF?’ The response was, ‘If you try to mail it out, we’ll take it.’”

In addition, J. writes, “D. and I wrote several pieces for newsletters. These were confiscated by an IGI officer and were used as ‘BGF gang material’ as a basis to deny D.’s inactive status.”

D., also at the Corcoran SHU, writes: “Think about this: I could write as many letters as I want and call someone as many ‘Ns’ as I want. Call women all manner of foul things. I can even compare the president to Adolf Hitler, and it would be cool: protected speech. But they have actually criminalized certain people, language.

“If they came in the cell and found an actual book marker that came from a vendor with books and the book marker had a drawing of a dragon on it, they would say that it’s gang activity. Some of this has sunk to such a low level that it would be as comical as it sounds were it not so destructive.”

D.’s reference to the potential for gang validation for saying something about a dead person is actually based on how he himself was validated. Gang validation documents sent to Solitary Watch indicate that among the pieces of evidence of gang activity in his case – which ranged from a confidential informant to his name appearing on a piece of paper in another inmate’s cell – was a eulogy he had written for a deceased African-American inmate who had been a BGF member.

While it cannot be definitively said that none of these men have ever been involved with the BGF, it appears from these and other instances of seemingly weak evidence of gang activity that prison officials may be overreaching in their efforts to curb legitimately disruptive gang activity.

Isolated for having a ‘gang’ calendar

“We have heard a lot about the gang ‘validation’ in California prisons – the process by which inmates are identified as members of prison gangs,” says James Ridgeway of Solitary Watch. “Validation can land a prisoner in solitary for five, 10, even 20 years and was the main focus of the recent hunger strikes at Pelican Bay and other California supermaxes.

The prisoner writes: “I am currently in the administrative segregation unit in a California prison. I was not placed in the ASU for any disciplinary reasons; I was placed here for having copies of a 10-12-year-old cultural calendar. I’m basically here for having copies of other people’s artwork that dates back up to 20 years. Because these individuals were deemed ‘prison gang members,’ I am deemed a ‘threat to the safety and security of the institution’ for simply admiring their artwork. How trivial is that?

“I’ve been in this situation for 15 months now. It is extremely mind-boggling how the state and courts allow the prison system to take all your little comforts, the things that help you feel like you are doing something positive with your time, such as education – I was two classes away from getting a second college degree – AA/NA classes, a job and a few hours of recreation a day over some innocuous copies.

“This is the first time, however, that we’ve heard of a prisoner being validated and placed in solitary for having a calendar that was deemed to be gang-related – proving, once again, that First Amendment rights often end at the prison gates.”

“Now I sit here day in and day out wondering if humanity has desensitized itself to the suffering of other human beings. It is incredible when I hear about the anger and moral courage some people feel at how a chicken or any animal is caged up but don’t bat an eyelash when a human being is treated worse. It simply amazes me.”

Solitary Watch aims to bring the widespread use of solitary confinement and other forms of torture in U.S. prisons out of the shadows and into the light so as to provide the public – as well as practicing attorneys, legal scholars, law enforcement and corrections officers, policymakers, educators, advocates and prisoners – with the first centralized source of background research, unfolding news and original reporting on solitary confinement in the United States. James Ridgeway is co-director and co-editor, and Sal Rodriguez is reporter, researcher and social media manager. Sal can be reached at rodrigsa@reed.edu. The first and second parts of this story first appeared on Solitary Watch.