by Jawanza Kunjufu

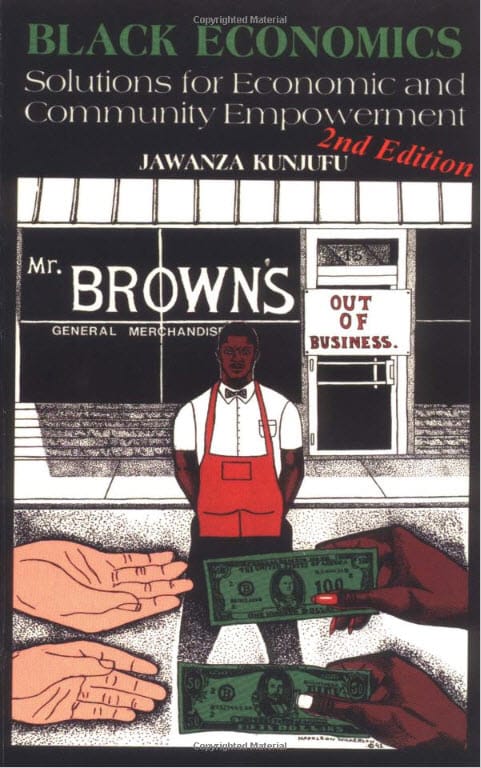

Carter G. Woodson in the book “The Mis-Education of the Negro” made reference to how schools encourage African Americans to pursue careers working and managing other people’s enterprises versus starting their own business. Schools feel that it is more prestigious to be an accountant for a Fortune 500 corporation than to own a grocery store or cleaners in the community. There is a perception that Black businesses are marginal, require too much work for too little income, and that it’s more lucrative, less demanding and more financially rewarding to work for someone else than to own your own business.

African Americans have the smallest rate of business ownership, compared with whites, Latinos and Asians. I think a major reason for this is that the social environment does not encourage people to start businesses. Many of the men and women who do form businesses start them after a great deal of frustration due to not being able to climb the corporate ladder. Some women within our community who have the time, money and maturity to raise children unfortunately are not having as many as those with the least time, money and maturity, who are having more children.

The same applies in the business community. Many of our best Black minds, who have the degrees in engineering, accounting, marketing and business administration are using their skills and talents for corporate America while other members of our community are starting “mom and pop businesses,” which reinforces that Black businesses are very marginal.

Many of us underestimate business viability. What we perceive to be a marginal operation in actuality is just the opposite when we total the business receipts for the day, week, month or year. I still regret that during the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, our people didn’t understand that after 381 days of creating an alternative bus service, freedom should have also been defined in economic terms.

We did not need to return back to riding their buses that were losing money because of our boycott. We should have continued on with the maintenance of our own bus system. This is a slave mentality of supporting and working for others versus ourselves in the African American community.

African Americans have the smallest rate of business ownership, compared with whites, Latinos and Asians. I think a major reason for this is that the social environment does not encourage people to start businesses.

Many of us look down on the grocery stores, cleaners and “marginal operations” because we lack a vision of how Ford, GM, Chrysler, IBM, Wal-Mart and others started as “marginal operations.” We were not there when they met in the basements of their homes developing strategies. We were not there to observe the 12, 16 and 20 hour work days seven days a week. We were not there when payrolls were missed and financial sacrifices were made.

We were not there when they borrowed money from relatives because they had a vision that years later they would have million dollar operations. I will never forget the day my mother loaned me $1,000 to start African American Images and how gratifying it is to see that seed money blossom. It has been said that a people without a vision will perish and, unfortunately, that is happening in the business sector of our community.

On the other hand, some of our people dream too much and businesses require more than dreams. They require hard work, sacrifice and planning. John Raye from the Majestic Eagles makes a distinction between a goal and a wish: “The latter, you never do anything about; the former, you work on it constantly.” Many of our people are so used to being involved in large corporations that it’s very difficult for them to imagine starting a business from scratch. As a person who’s a strong advocate of self-esteem, I never want to burst anyone’s bubble or destroy their dream.

Another obstacle affecting Black economic development within the business community is the lack of trust. It is very difficult to do anything in this world by yourself. The same cooperative spirit that Asians and other immigrants have in studying together they replicate in the business sector by pooling their resources. This level of trust is necessary if a business is going to be successful.

Prosperous businesses establish and maintain trust with their customers, workers and investors. It becomes imperative that if we’re going to be successful as business owners we have to acknowledge that trust is as essential an ingredient as capital and business acumen.

Another obstacle that affects Black businesses is the desire to convince themselves, their families and their communities that their businesses are viable. This is demonstrated by the purchase of expensive clothes, cars and houses. Many business owners fall prey to materialism and the desire to refute this image.

Black businesses become marginal by making expensive purchases – the assumption being that my business can’t be marginal if I’m driving a Cadillac, BMW or Mercedes. The reality is those kind of purchases rob a business of necessary capital for future growth and development. I’m not saying that Black business owners should take an oath of poverty and never utilize some of their business resources for personal pleasure, but I do feel that balance and moderation are essential.

I recognize that many of our people view Black businesses as being marginal and this is one opportunity for refutation, but there are other alternatives to convincing the larger community that Black businesses are viable and need to be pursued. The Black business community and the teaching profession need a major public relations campaign to communicate their tremendous benefits.

Another major obstacle to Black economic development is the attitude of the Black consumer. I often ask Black consumers several questions: What is their commitment to the race, how much value do they place on Black businesses, and is their loyalty greater than a penny or a nickel?

I heard a horror story recently from a Black business owner who had been in business for several years. A foreigner opened up a business and was selling the same hair care product. His store sold it for $4.99 and the foreigner sold it for 4.95. He told me there was a marked decline in the sales of this particular product and that African American customers were telling them that his prices were too high, only for him to find out that the difference in price was a mere four cents.

Again, I raise the question, how much loyalty do we have to the race? Can it be bought for a penny, nickel or dime?

Jawanza Kunjufu is the author of 33 books, including “Black Economics,” and has been featured in Ebony and Essence and on BET and Oprah. He is happily married to his best friend and business partner and mentors boys in the Community of Men organization he founded. This story previously appeared at The Imani Foundation.