by Charles W. Davidson

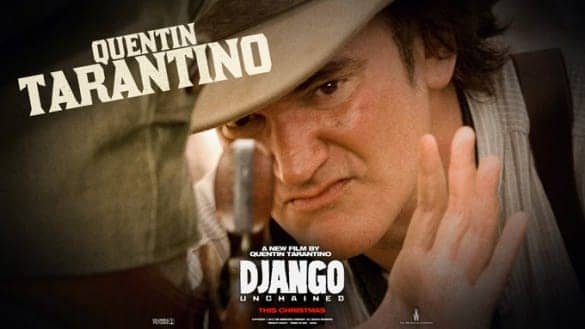

By now, movie-goers across the country are embroiled in heavy social media discussions or water cooler arguments about Quentin Tarantino’s use and Spike Lee’s criticism of said use of the infamous N-word in the blockbuster hit “Django Unchained.” There are those who believe that the word is grossly overused in the film starring Academy Award winner Jamie Foxx, Leonardo DiCaprio and Kerry Washington. Then there are those who believe that the film’s utterances help to present a sometimes painful yet accurate depiction of pre-Civil War America.

The problem is, the word “Nigga” and the word “Nigger” are similar but strikingly distinct in scope and meaning. The use has evolved but the context is forever bound to a hurtful past that extends to the present. Surprisingly though, many whites seem unwilling or unable to understand the nuance involved. In this article I attempt to explain what people of African descent have been both uninterested in divulging and at times unable to express about a word pregnant with subtext.

The word “Nigga” today is a convergence of mostly positive ideas. It is the combination of an ethno-universal acknowledgement of survival, triumph, struggle and understanding coupled with very light underpinnings of the original intent of the word’s creators. The abominable original intent is important to the modern understanding.

So when I extend a greeting to another Black man such as, “My Nigga, what’s up?” What I am actually saying is; “My descendant of slaves who has endured the same struggles, injustices, oppression and experiences in America and still persists by whatever means, what’s up?” Yes, the subtext is that specific.

If I were to utter a phrase such as “Those Niggas make me sick,” the meaning is the same with a slight adjustment. While I may disagree with the actions or general life orientation of the Black men I am referring to and seek to express my discontent with them, I acknowledge our common bond, common suffering and common ancestry by calling them “Nigga.”

I do understand that there are those who call everyone they see the N-word whether they are white, black, orange or green. In this context the N-word becomes an Ebonic colloquialism such as “fool” or “dude.” Ironically, this practice has been widely adopted by youth from varying ethnic backgrounds in the last few years. Surely a result of the pervasive nature of Hip Hop music. Furthermore, though many would argue the word is intended to refer to males, it is often used in a way that is not gender specific.

The word “Nigga” and the word “Nigger” are similar but strikingly distinct in scope and meaning. The use has evolved but the context is forever bound to a hurtful past that extends to the present.

“Nigga” among African Americans in 2013 is in its simplest form a moniker that denotes kinship in several realms as mentioned previously while at times simultaneously maintaining the adverse connotation intended by the white originators. We have enjoyed a Black president for more than five years now and the gains of the Civil Rights Movement are clearly visible. Yet the N-word today represents the common systemic oppression and experience with structural white supremacy that is still very evident in the United States and around the word.

But should the word be “unchained,” so to speak? That is a question for posterity. In many ways, it already has been “unchained.” Quite frankly, it should indeed make white people nervous and uneasy in this writer’s opinion. However, it should not make them jealous, as often seems to be the case.

More often than not, whites seem to feel entitled to all facets of American society and culture, including free moral reign in spewing one of its most repugnant expressions. Perhaps Quentin Tarantino feels a sort of vindication in his use of the N-word in life and via the characters in his films. None of us can ever know this for sure. I think many would agree that he seems to take pleasure in rebelliously peppering his films with whites and Blacks alike who spew both versions hundreds of times.

So the next time you hear a person of African descent refer to another person of African descent as “Nigga” endearingly or otherwise, if you are white, seek to understand that their use of the term is pregnant with historical context mostly acknowledging common hardships, kinship, pride and perhaps even a tinge of vitriol – but know that today’s word is light years removed from the term from which it originates.

Whites seem to feel entitled to all facets of American society and culture, including free moral reign in spewing one of its most repugnant expressions.

Many whites do indeed possess a deep empathy for and uncommon understanding of the issues of the Black Diaspora. However, their use of the word even when well intentioned can never be fully accepted. While Quentin Tarantino is an immensely talented auteur who has proven that he excels in telling even the most controversial of stories, in one way or another, the N-word will never fully be “unchained” for his use in the psyche of Americans at large. There is simply too much hurt still hidden in plain sight to remove the shackles so quickly.

Charles W. Davidson, born and raised in Nashville, Tenn., is an award winning director, screenwriter and producer in Los Angeles and alumnus of Atlanta’s Morehouse College. He can be reached at charlesdavidson2@me.com. Visit his website at http://www.charlesfilms.com/.