By James Ridgeway and Jean Casella

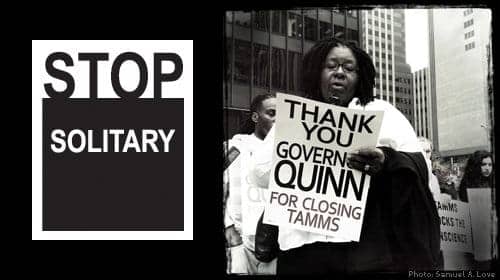

On Jan. 4, 2013, Tamms Supermax in southern Illinois officially closed its doors. The prison, where some men had been in solitary confinement for more than a decade, had become notorious for its brutal treatment of prisoners with mental illness – and for driving sane prisoners to madness and suicide. The closure of Tamms, under order of Gov. Pat Quinn, was celebrated as a victory by human rights and prison reform groups and by the local activists who had fought for years to do away with what they saw as a torture chamber in their own backyards.

The battle over the future of Tamms became the most visible and contentious example of a phenomenon seen, in one form or another, around the country: Otherwise progressive unions are taking reactionary positions when it comes to prisons, supporting addiction to mass incarceration. And when it comes to issues of prisoners’ rights in general, and solitary confinement in particular, they are seen as a major obstacle to reform.

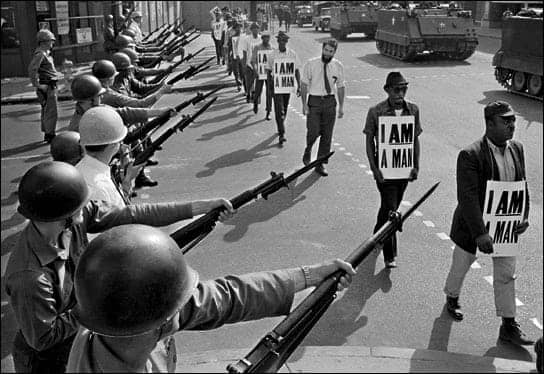

With more than 1.6 million members nationwide, AFSCME is generally viewed as a liberal-minded organization that played an important part in developing the trade union movement in the public sector. It was during a march in support of an AFSCME strike in Memphis that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Today AFSCME is seen as a prime labor force behind Obama’s presidential victories, a great backer of health care reform and, in a time of labor’s decline, the biggest organizing union in the AFL-CIO.

In a commentary in the Chicago Sun-Times, scholar and activist Stephen F. Eisenman of the group Tamms Year Ten pointed out that in the 1960s and ‘70s, “AFSCME’s leadership understood that workers’ rights and human rights were inseparable.” Then-president Jerry Wurf, he writes, “combined compassion with organizing zeal. When the big psychiatric hospitals, such as New York’s Creedmoor, were being decertified, he did not argue to keep them all open. Instead, he fought to ensure that de-institutionalized mental health patients received adequate community and home care.

“Because he knew these hospitals were hellholes, he was willing to sacrifice some union jobs for the good of people with mental illnesses. But Wurf lost that battle. The national recession of the 1970s intervened, and a generation of patients were turned out in the streets without proper support. These are precisely the people who now fill our nation’s jails and prisons.”

Around the country: Otherwise progressive unions are taking reactionary positions when it comes to prisons, supporting addiction to mass incarceration.

Today, in contrast, AFSCME fights to keep these prisons open even when no jobs appear to be at stake. From the start, all of the union’s members working at Tamms were guaranteed placement in other prisons, and no jobs were lost when the supermax closed. But the union took the position that conditions at Tamms – which had been widely denounced as cruel, inhumane and ineffective – were necessary to maintaining prison safety and security, as well as keeping jobs in southern Illinois.

In response, Tamms Year Ten mounted protests in which prisoner’s family members held signs stating, “Torture Is a Crime–Not a Career,” “My Son Is Not a Paycheck,” and “We Support Unions That Support Human Rights.”

AFSCME is just one of four large unions that represent prison employees, along with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) and the Teamsters. In addition, corrections officers in a number of state prison systems, and even some local jail systems, have unions of their own – such as the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), the New York State Correctional Officers and Police Benevolent Association (NYSCOPBA) and the Correction Officers Benevolent Association (COBA) of New York City.

The overall picture of prison unions is one of defense and decline, with their interests focused squarely on protecting jobs at all costs. In some instances, this has led them to take positions that align with those of progressive prison reformers. Both share concerns about overcrowding and understaffing.

In the recent Plata case, in which the Supreme Court ordered California to reduce overcrowding in its prisons, the state correctional officers’ union argued that “CCOPA members’ daily work experiences reveal an overcrowded, inadequately staffed system that cannot deliver adequate medical care in spite of the best efforts of prison employees.” As CO (correctional officer) Gary Benson explained at trial, there are “way too many inmates in that small of a space to do the job”

“Privatizing prisons for profit is immoral,” said AFGE’s Dale Deshotel, who heads up prison locals within the national union. “If we have a society and control it with laws, if you break the law, then state or government should handle that function … private prisons don’t want people who are high security problems. They want low security people … it’s a money making project. In private prisons there is no programming for rehabilitation, for education.” SEIU spokesperson Kawana Lloyd said: “The for-profit companies reduce safety, bring down standards and have corrupt relationships with politicians.”

But preserving jobs generally means keeping as many people as possible in prison for as long as possible, which clearly runs counter to the goal of reducing mass incarceration. CCPOA, for example, was one of the primary sponsors of the proposition that led to California’s Three-Strikes Law in the 1990s, opposed parole reform in the 2000s and vigorously campaigned to defeat politicians it regarded soft on crime. It continues to support the death penalty.

From 1982 to 2011, the union’s membership grew by about 600 percent, from 5,000 to 31,000. The organization’s finances also expanded. “Whereas the CCPOA had approximately $500,000 in 1982, the union’s budget in 2002 was roughly $19 million,” according to Joshua Page, a University of Minnesota professor and author of the book, “The Toughest Beat,” who has written extensively about the union. More recently CCPOA is seen as moderating its positions somewhat, says Page, but it remains a potent political force in California, which has the largest prison population in the country.

Today, in an era where there has been growing interest in cutting state and local budgets, including the costs of prisons and jails, unions have fought against prison closures and programs that would divert offenders into treatment programs and other alternatives to incarceration. Within the prison environment, unions have frequently opposed reforms that could be seen as reducing their members’ power or autonomy. These include oversight aimed at reducing abuses by corrections officers and other prison officials.

When it comes to solitary confinement specifically, several unions have stood up to resist a growing tide of reform that condemns long-term isolation as not only torturous, but also counterproductive to the goal of prison safety. States that have dramatically reduced their use of isolated confinement have seen prison violence drop as well.

Yet in Illinois, AFSCME continues to argue that closing Tamms has put its members’ lives in danger. In New York City, COBA was a major force behind the building of nearly a thousand new solitary confinement cells on Rikers Island, blaming a rise in violence on the supposed “shortage” of isolation beds.

In Maine, the union backed Warden Patricia Barnhart, thought of as being an old guard, hard knocks warden, before she was recently fired by state Corrections Commissioner Joseph Ponte. Ponte, who has gained a national reputation for cutting down the use of solitary at Maine State Prison, replaced Barnhart with Roy Bouffard as acting warden. Bouffard is a reformer and told Lance Tapley of the Portland Phoenix: “I’m definitely going to soften” the process at the state prison.

States that have dramatically reduced their use of isolated confinement have seen prison violence drop.

Officially, the big unions have shown little if any interest in taking a position on solitary confinement. AFSCME represents 62,000 corrections officers and 23,000 corrections employees nationally, according to its website. Asked if the national discussed prison reform or had anything to say about solitary, Chris Fleming, a spokesman at Washington headquarters, said, “We have not taken a position nationally on these issues.’’

The American Federation of Government Employees, whose members total about 278,000 in more than 100 federal agencies, represents 24,000 prison employees of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. In a phone interview, AFGE’s Dale Deshotel was more expansive. “In many cases I wish we had the space for solitary confinement. Some of them deserve to be alone. They are very dangerous. In fact in some of our prisons, we’ve got to keep them separated because of the possibility they would hurt one another or create problems for us,” he said.

“I do know people should be treated with dignity. However, a person in prison for violent acts and cannot control himself or herself, there are times they need to be isolated … our own psychologists have their interpretation how long. But I know in my 26 years, early on where we had the opportunity and had the space to isolate an individual because of their conduct, it takes a few days for them to realize what they want.”

He continued: “It does have an effect on a human being. We are not built that way, created that way, to live in isolation. However in a prison setting where an individual refuses to program or cooperate, if we had the opportunity, we would use it much more. But we are so overcrowded that our hands are tied. We struggle to find the empty space to isolate some of these people … People who can’t function we cannot tolerate and we will not tolerate it. That’s different from putting someone in a room for no real reason.”

In Illinois, where AFSCME has lost the fight to keep Tamms supermax open, it nevertheless continues a public relations campaign against the closure.

Asked whether SEIU has taken a national position on solitary, Kawana Lloyd said, “Definitely not.” She added, “We have around 25,000 correctional officers in our union. Our two largest units are Michigan and North Carolina. Both places are facing privatization challenges.”

“The Teamsters represent 1.4 million members in the U.S., Canada and Puerto Rico,” Leslie Miller, communications coordinator for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, wrote in an email. “We represent 20,000 Florida Department of Corrections officers in Florida, but since it’s a right-to-work state the number of actual dues-paying members is smaller … We also represent corrections officers in Washington State.” Miller continued, “I don’t believe the International Brotherhood of Teamsters have taken a stand on solitary confinement, and I don’t think the Florida local has taken a stand.”

But in local fights over solitary confinement, unions have taken positions squarely in favor of maintaining extreme isolation practices. In Illinois, where AFSCME has lost the fight to keep Tamms supermax open, it nevertheless continues a public relations campaign against the closure. Recently, it sought to link the end of the supermax to three assaults on COs at other prisons – even though none of the prisoners in question had been transferred there from Tamms.

James Ridgeway and Jean Casella are co-editors of Solitary Watch, an innovative public website aimed at bringing the widespread use of solitary confinement out of the shadows and into the light of the public square. Solitary Watch, where this story first appeared, provides the public – as well as practicing attorneys, legal scholars, law enforcement and corrections officers, policymakers, educators, advocates and prisoners – with the first centralized, comprehensive source of information on solitary confinement in the United States.