Review by Orissa Arend

“Snakes and Ladders,” the title of one of the 22 map chapters, is an ancient dice board game played in India to teach children how good and bad deeds carry a person up or down in life. The goal is to get to God, as opposed to the game’s contemporary counterpart, Chutes and Ladders, where the goal is simply to win.

Why all these maps? They seem retro in this digital age where we navigate from computer-generated orders. “A great map should stir up wonder and curiosity, prompt revelation, and deepen orientation. It should make the strange familiar and the familiar strange.” After reading this book you’ll want to go out and map things that are important or quirky to you. If you are of a certain age, you will remember your childhood fascination with treasure maps.

The map/essay called “Stationary Revelations: Sites of Contemplation and Delight” is a treasure map of sorts. Like Walker Percy’s Binx in “The Moviegoer,” this chapter’s author, Billy Southern, prompts us to live here as if we were castaways, poking around, searching, fighting despair and the “everydayness” of life by finding treasure like the red shotgun double on Jackson Avenue where trombone great Kid Ory lived from 1910-1916 or the parrots from Argentina which have created a massive home for themselves atop Reading Radio’s tower on Magazine Street.

Lolis Eric Elie writes about ethnicities in New Orleans. An accompanying map by Solnit and Snedeker charts them not with nouns but with verbs of people’s avocations: People who: live near their cousins, take bribes, are polyamorous, eat frozen vegetables, face Mecca, shop at malls, are kings and queens, barbecue on the streets, etc. All set to Bunny Matthews’ uber-expressive illustrations. You’ll want to find yourself on this map.

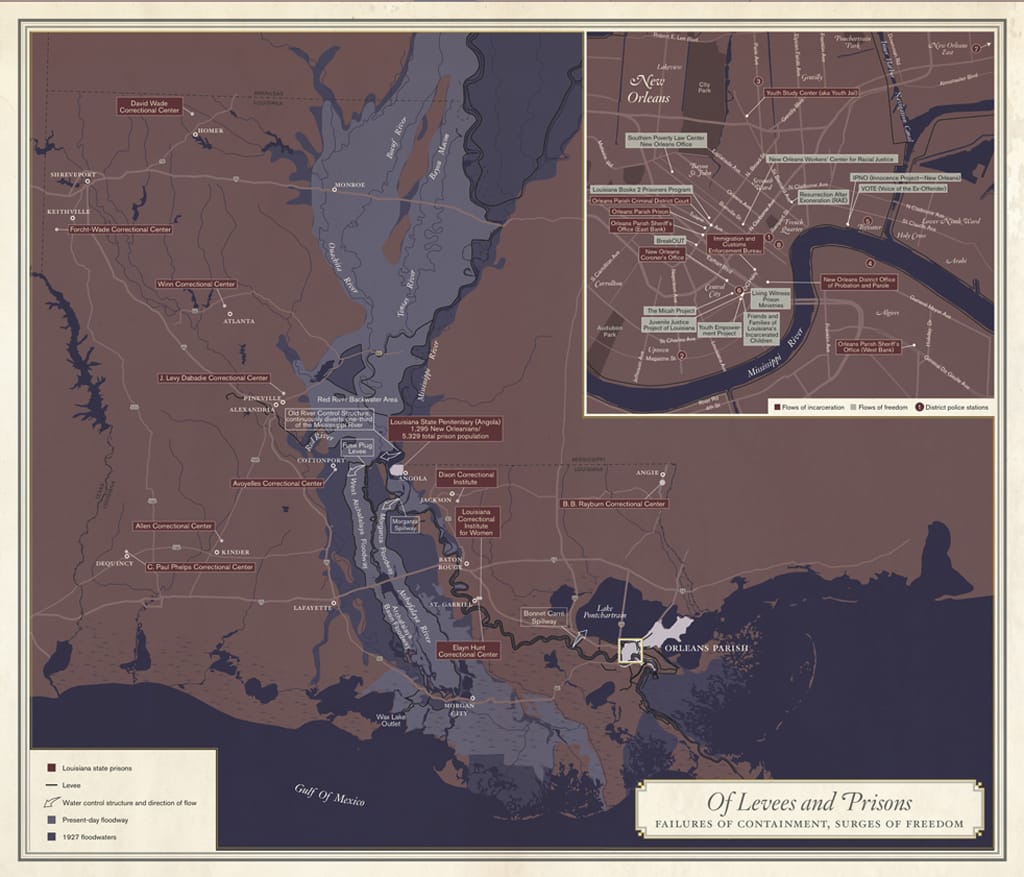

Incarcerated activists “first identified the ballooning of Louisiana’s prison system as a white supremacist project.” The prison newspaper The Angolite published the evidence. Jailhouse lawyers organized voting blocks of outside allies to push for prison reform and to have decades-long solitary confinement declared cruel and unusual punishment. Freed activist and former Black Panther Robert King continued to fight for his friends Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace (now deceased) on the inside and to free political prisoners everywhere. Freed activist Norris Henderson helped found Safe Streets/Strong Communities and Voice of the Ex-Offender.

The map here depicts flows of incarceration and flows of freedom, levees and floods, showing that “where even the river has been arrested and imprisoned, … water still flows, resistance still flows, communication still flows between New Orleans and the prisons … freedom is not entirely dammed up, not by any count.”

There are other unusual combinations. “Civil Rights and Lemon Ice” traces the lives of three people. Paul Trevigne was a free person of color who helped launch one of the first movements for racial equality in the country. Angelo Brocato was a Sicilian immigrant who opened an ice cream parlor over a century ago when the French Quarter was 80 per cent Sicilian. Playwright Tennessee Williams arrived in the French Quarter on New Year’s Eve of 1938 almost penniless. The trajectories of their lives are mapped together.

Rebecca Solnit, who created a similar atlas for San Francisco, and Rebecca Snedeker, a local filmmaker (“By Invitation Only”) enlisted a remarkably diverse and talented team of writers, artists, researchers, cartographers and graphic designers – about 40 in all – to work on the book. In the process they created something unique and personal, a collection of secrets about a city that died and was reborn. “Everyone loves a secret,” says Snedeker, “except when they are left out, and this book invites people in.”

Orissa Arend is the author of “Showdown in Desire: The Black Panthers Take a Stand in New Orleans.” You can reach her at arendsaxer@bellsouth.net.