Radio interview between host Dee LeComte and guest Keith LaMar (Bomani Shakur), broadcast on Prison Radio Show, CKUT 90.3 FM in Montreal

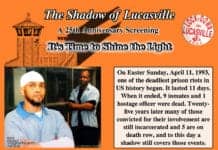

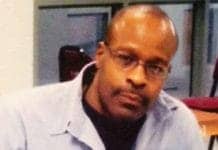

Dee: Keith LaMar, also known as Bomani Shakur, is a prisoner in Ohio, condemned to death on false charges following the 1993 Lucasville Prison Uprising. Bomani is one of five men condemned to death after being railroaded through forced snitch testimony. They are known as the Lucasville Five.

According to the state of Ohio, Bomani was said to have been responsible for ordering the deaths of five prisoners, a charge that came only after Bomani refused to cooperate and implicate himself in crimes that he was innocent of. The prosecution knew that he was innocent, but they also knew that because of his criminal record, he had no credibility in the eyes of the legal system when he proclaimed his innocence during his trial.

Keith LaMar is the author of “Condemned.” This book is the first-hand account of his experiences during and as a result of the Lucasville Prison Uprising of 1993. Bomani vehemently denies any participation and sets out to prove to readers how the state of Ohio knowingly framed him in order to quickly resolve, under great public pressure, their investigation into a prison guard’s death.

The following is an interview with Bomani from death row, recorded on March 7, 2014.

Dee: Hello Bomani, and thank you for being with us today.

Keith: Yes, how are you doing? Thank you very much. I’m glad to be here. Glad to be with you.

Dee: You are part of the Lucasville Five. I was wondering, though, if you could explain where is your case at this time?

Keith: Yes, I’m a part of the Lucasville Five, but we don’t have the exact same cases. In fact, my case is very different from theirs. I just filed my last appeal. Their cases, because of legal proceedings, are on hold right now as their attorneys are given the opportunity to comb the prosecutor’s file. My case is proceeding along against my wishes.

Right now, I’m awaiting a date to be set for oral arguments in my case. That entails my attorneys and the state attorneys coming before a tribunal of three judges and both arguing our opposing sides. After that, the judges will take my case under consideration and render their decision as to whether or not I should live or die.

So my case is really at the crucial point. It’s really at the point where things are very, very serious. I don’t want to make it seem or sound like I’m distancing myself from the Lucasville Five, because those guys have been with me from day one, but the Lucasville Five is just a name to indicate or point out that we have been sentenced to death as a result of the Lucasville Uprising.

Two of those guys are Sunni Muslims and two of them are members of the Aryan Brotherhood. One has since denounced his membership to that gang, but nevertheless, that was the reason that they were sentenced to death, because of their alleged leadership roles in these gangs.

I, on the other hand, am not and never have been a part of a gang. I was rounded up in a separate sweep of inmates who filtered out onto the yard on the first day of the riot. As some of your listeners might know if they are familiar with the story, the riot lasted for 11 days. And of those 11 days, I was picked up during the sweep on the first day of the riot.

So I wasn’t involved in the riot, per se. I only became a suspect – and then later was accused of being a perpetrator – when I and several other inmates staged demonstrations to protest the unjust conditions that we were being subjected to. I also came out – vociferously came out – against anybody becoming informants to help the state with their investigation. Because of my involvement in these demonstrations, I was singled out and charged with, saddled with, these cases.

Dee: You were mentioning earlier that it could be any time that you could be going to a court now. Do you think that you’ll get this discovery, this evidence that was suppressed during the trial?

Keith: Well, discovery – it’s not a matter of whether or not I’ll get it. As I explain in the book, in 2007 I had an evidentiary hearing in my case. And I, along with my attorneys, went back to federal court and we were able to question the prosecutor, the lead prosecutor who put together these cases against us.

And while my attorneys were questioning him, he admitted that he used what was later termed a “narrow standard” to determine what evidence to turn over to the defense. In fact, he created an impossible standard. He made it impossible for us to receive this evidence, this favorable evidence, so I didn’t really have a trial, per se.

The only thing I was able to do in terms of defending myself was call witnesses who saw me on the yard during the time these murders were allegedly taking place. I didn’t find out until months and years later that some of the crimes for which I was convicted – that other guys had been indicted for those very same crimes.

In one instance, I have the actual statement of a guy who confessed to killing one of the inmates for whom I was convicted and sentenced to death. And during this evidentiary hearing that I’m speaking of, the prosecutor admitted these things.

I shared the same magistrate judge as Siddique Abdullah Hasan, but we had different district judges. And his district judge granted him leave, or granted him permission – since they used this narrow Brady standard that I’m speaking of – through his attorneys to go back and review the files and determine for themselves what constituted favorable evidence.

Since the state, by their own admission, withheld this evidence, I asked my attorneys to do the same thing and for some unknown reason they refused. So I haven’t really spoken to my attorneys, except briefly once or twice, for over a year now, because they refused to file these necessary and most important papers on my behalf.

And so this oral argument that I’m awaiting, it’s really a shaky situation because the attorneys who refused to file these motions are the very same attorneys who will be standing up at my oral argument and speaking on my behalf.

You asked how can I be provided this discovery? Well, they needed to file these motions but they refused to file them, so I’m going into this final phase of my appeal really unequipped to fully demonstrate the injustice that was done against me. That was the whole purpose behind writing the book: to inform the public and to hopefully get them engaged in this struggle, so that I can have some momentum going into this last phase of this journey. Yeah.

Dee: So that answers my question, that is, why you wrote the book “Condemned.” What do you hope that it will bring to the public, where it concerns political discussions surrounding prisoners’ rights, as well as the death penalty at large? I understand that you are focused a lot on your case, because it is a matter of life or death if you are going to be a victim of state-sanctioned murder.

Keith: That’s right.

Dee: But maybe if you can talk on it a little more, on a broader level, too?

Keith: Yes, you know, as I tell people that listen to these talks, it’s bigger than me. I’m talking about my case because this is my life and I would like to do everything I can to preserve it. But really, on a larger perspective, it’s about poor people.

It’s about what can happen to you when you’re poor in America, in the richest country in the world. It’s about the fact that there exist two justice systems: one for the rich and one for those without money.

It’s about solitary confinement, about this new form of incarceration that is being applied in various states to silence and torture inmates who don’t have any sense of what’s going on in the world.

So I speak about these things, but I speak about them to get people who are engaged in these things to read between the lines and understand that this is what real justice looks like when you’re poor. That’s one of the larger issues I’d like people to become aware of. And also by lending their support to me, they’ll be lending their support to other poor people who are on this path.

Recorded operator: You have 10 seconds left on this call.

Dee: You are listening to the voice of Keith LaMar, speaking from death row at the Ohio State Penitentiary. We are interrupted by the automated prison phone, and when Bomani calls back we continue our discussion on prisoners’ rights and the death penalty at large. We ask him what he wants the public to know about these issues.

Keith: I want the public to understand that the narrative they are being presented with is not really accurate. They are being told that poor people, that we are in prison because we are morally defective, that we are solely responsible for the crimes for which we have been imprisoned, so they have the public under the impression that we deserve to be here.

That was the explanation for a time, but the United States, one of the most powerful countries in the world, has the largest prison population in the world. More than South Africa and Russia. So people need to start taking a closer look at what incarceration means in the richest country in the world.

We live in a society now that no longer has a purpose for the poor in terms of jobs, in terms of being able to live a meaningful life. And so the answer to that problem from the perspective of those who own society is to get rid of people.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that what’s going on in the United States is similar to what was going on in Germany in the 1940s. And just as Hitler created the justification for the mass extermination of the Jews, I believe the United States has created the justification for the mass incarceration of the poor. The parallels are there.

We live in a country where the wealthiest 1 percent own close to 50 percent of all the wealth and resources, and it’s because of these disparities, these economic inequalities – inequities – that people are forced to live these half-butchered lives.

They think that the narrative is that we come to prison because we’re trying to gain riches, but we’re here, we’re trying to survive under these hellish conditions. People have these stories about gangs, but you join gangs because there’s safety in numbers.

These crucibles that have been created because of economic injustices, they are very violent places. They are very violent places – and they continue to be violent once you are in prison – so you group together with these other individuals to protect yourself, to survive.

And see, that’s what people need to understand about what economic injustice entails. As more and more people are classified as poor, as more and more people fall into the bottom stratum of society, then they themselves are going to become classified as criminals.

So before that happens, before your son comes to prison, before your father is sent to prison, I want people to understand that they need to get involved in the struggle. From the perspective of the rich – they look at us as superfluous, as garbage.

My story is just a small example of this larger thing that I’m talking about. I’m just one person, but this is happening to millions of people. I’m facing execution, but other guys are facing a different kind of execution, a different kind of death, a “social death,” as Goffman would put it, a social death where they are being sentenced to inordinate amounts of time.

You know – 20, 40, 50 years – guys have these crazy sentences because they are responding to the realities that they live through in these environments that they’re in. They are responding to those realities; and their reactions to the degradations and deprivations are sending them into these places.

So that’s one of the larger things that I try to speak about. It’s bigger than me. It’s bigger than what’s going on with me personally. You talk about the Lucasville Five, but it’s really just millions and millions of people who are being caught up into this net, who are being thrown away, essentially. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of dumpster diving?

Dee: Yes.

Keith: It’s a thing where you go in the garbage and you find things that are salvageable. You know, furniture, food. People in the richest country of the world, people live off what they find in dumpsters. And these items that you find in the garbage can, what qualifies them as being garbage is that you can no longer make money off them, so if it’s past its due date they throw this stuff away. But this is stuff that people in third world countries and other countries can subsist on, and the same thing is true when it comes to human beings.

We are being thrown away because they can no longer make money off of us. We can no longer find a way to survive under the system that they have created, so we’ve been thrown away – not because we don’t have value but because they can no longer make money off us.

This is the thing that people have to understand, that really this thing has to stop, ‘cause it’s getting to the point now where you have no middle class, no buffer between these stark realities of these super, super rich people and these super poor people. We’re coming face to face, and so people have to really decide and think about where they’re going to stand in this situation that we’re in.

And so I’m just lending my voice to the millions of voices who are standing up and starting to speak truth to power. I’d like to be a part of that movement. That’s another reason why I wrote the book, so that I could add my iron to fire. Because it is a fire.

Dee: Why do think that the state needs to put you to death? You’re innocent. There’s been a lot of, there’ve been documentaries made, other books written. So why does the state need to put you to death?

Keith: Because I stumbled up on something. I was sentenced to solitary confinement. I’ve been in solitary confinement for 20 years now, and instead of watching television I decided to read. I decided try to learn why my life ended up this way. And I started reading Karl Marx. I started studying economic theory, social theory, you know, and I stumbled up on something.

What I stumbled up on is that this system is a sham. And, yes, I am guilty of committing certain crimes that led me to prison. But I’ve learned that there’s a difference between guilt and responsibility. For instance, a person could be guilty of selling marijuana, but not at all responsible for the conditions where selling marijuana is the only viable way to survive.

And I stumbled up on this and I started sharing this knowledge with other inmates, with other prisoners. And so they put me in solitary. I believe the reason they want to execute me is because I stumbled up on something that they don’t want me to share with other prisoners. I think that ultimately is the reason why.

And I talk about this, how I was selected as the so-called leader of this “death squad.” But it was only after, as I said earlier, I had participated in the demonstrations and whatnot. But after the riot and after all this stuff that I had endured and was put through, I was also studying.

There’s a difference between guilt and responsibility. For instance, a person could be guilty of selling marijuana, but not at all responsible for the conditions where selling marijuana is the only viable way to survive.

I was reading George Jackson. I was reading Assata Shakur’s book. And through these people, these guides, I was able to find my way to a critical analysis of the situation that I was dealing with. And I just started speaking truth to power. I stood up and made myself a target.

But, you know, as I also present in the book, there’s no evidence linking me to these crimes. And as I mentioned earlier, I have actual statements from inmates who confessed to the very murders for which I am now being threatened with death.

And because I was poor and wasn’t able to pay for legal representation and whatnot, the [prosecution] didn’t do a thorough job, because they assumed that – and probably correctly – who is going to give a damn about a poor man? Who is going to give a damn about this criminal?

At the time I was in my early 20s. I didn’t know how to read, let alone write, so I had to teach myself how to read and write. What I mean by read, I mean comprehend what Karl Marx is saying when he’s talking about dialectical materialism. You know? So I had to teach myself how to read, because we aren’t really being taught how to think in these public schools that we are being turned over to when we are 5 years old, being indoctrinated and being told what to think, not how to think.

And so I had to teach myself how to read and write. And once I learned how to read and write, I started teaching other prisoners how to read and write, how to understand what they’re dealing with. And on that basis, I made myself into a threat, unwittingly.

Dee: So the reason that the state needs to put you to death is because of your threat in educating yourself, as well as the other prisoners, about the realities that brought you to prison?

Keith: Right. Right, because I stood up. Initially, it started that I stood up and persuaded guys not to become informants after the riot. You know, because I felt like we were left for dead, literally left for dead. And I explain that in the book.

And after all was said and done, the same people who left us for dead turned around and asked us to become informants. And I said, “Fuck that. To hell with that.” And, unknowingly, unbeknownst to me at the time, that was really what turned my life around.

They said I was the leader of a group that they dubbed the “death squad” and said I presided over the deaths of five prisoners. But no sooner had they indicted me that they came and offered me a deal. They asked me to cop out to murder and the time would run concurrent with the time I was already doing. They really just wanted to use me to clear their books. I was already serving a sentence of 15 years to life, which is essentially a life sentence with the possibility of parole, and from their perspective, I had nothing to lose.

They saddled me with these crimes, expecting that I would cop out, expecting that I would take a deal. But I’m innocent. So I refused the deal and went to trial, under the impression that I would receive a fair trial, under the impression that the jury would hear the evidence and exonerate me.

But I was in for a rude awakening because I didn’t receive a fair trial. I didn’t have access to the evidence that would allow me to confront my accusers. I wasn’t given that. I was deprived of these things.

And so that’s what I want people to understand: There are two systems. And we hear all this talk of innocent until proven guilty. We hear all this talk about justice, about equality, but those things are commodities in a capitalistic society and are reserved, you know. Justice is only available if you have money to pay for it.

Justice is only available if you have money to pay for it.

Dee: You want to use your book as one way to show the public what is happening and how this can happen and has happened to others before you. So what would you like to say to activists – not just those working on your case, but people who might be interested, people who are interested in prison issues. Do you believe that enough could be done to set you free? The reason I ask is because think of the case of Troy Anthony Davis.

Keith: Right. I understand what you’re saying. First of all, I’m already free. And that’s the problem, you know? I’m already free and the thing I try to get activists to understand is that people are dying who can be saved. We all – Michelle Alexander, Tavis Smiley, all these various people writing our books – are going around – everybody’s talking about what’s going on.

But let’s really talk about it. People who benefit from the system, who benefit from the failures of the system, those are the very people who are in the position to change the system, so we need to confront these people with the truth. I’m not under the impression that this book is going to help save my life. It’s not really about that. All of us are going to die at some point. And that’s not really the problem.

Dee: I was speaking with somebody who did do time for murder here in Canada, who’s out now. He asks this: “If you are killed by the state, do you think your death will change anything?”

Keith: Well, you mentioned Troy Davis earlier. And as you know there was a big movement surrounding his case, and he was executed. Now a year and some months later, you very seldom hear about Troy Davis, and yet the conditions that created the injustice that Troy Davis faced are still present. That’s what I was saying earlier.

I’m not under the impression that my death will change things. But the problems that we’re talking about have existed for centuries. This is not new. Capitalism has been around for hundreds and hundreds of years. So I’m not under the impression that my death is going to change the direction of this system.

But, see, that’s what I’m saying: It’s not really about dying; it’s about living. That’s what life is about. So I’m not scared to talk about death. I think Troy Davis and the movement that he started – I think we need to pick back up on that, but with a stronger and different message.

The fear of death – people need to get away from that, because there’s a difference between dying a death and living a death. And that’s what the majority of us are living, so that just a few people can live lives of luxury; and that’s the problem. Of course I want to be free to be home with my family and my loved ones, to wake up in my own bed, to eat my mother’s cooking, but there are more important things than that. And, see, that’s what I’m trying to get across.

Yes, I want to survive. Yes, I want to circumvent my execution. Of course I do. But on my way to that, I want to also lend my life to this struggle that’s speaking truth to power. Because that is what my life is about, that’s how I want to use MY life. That’s the thing that I have control over.

I don’t have control over whether or not they’re going to execute me. I don’t have control over whether or not the sun is going to set tomorrow. But what I do have control over is what I’m going to do with my time.

I’m trying to persuade activists and people who understand the injustices and the inequities of this system to get involved and give your life up so that somebody of the future generation – I’m ready to give my life up so that my nephew won’t have to be in prison. So that my nephew, so that the young males in my family won’t have to face execution. That’s what this is about. I’m ready to die if that’s what I have to do.

Dee: Phew!

Keith: That’s what I’m saying. It ain’t about dying. It’s about living. So that’s the thing that I’m talking about in my book. Not just about what the state did to me, but what I did TO the state. I understand that they were trying to break me. I understand that they were trying to separate me from myself. But it didn’t work.

And that’s what I’m trying to get people to understand: That we can fight these people, that we can overcome these people if we could just have compassion for each other, and that if we could somehow cultivate a love for each other, we could beat these people, ‘cause there’s more of us than them.

Dee: Could you give us some concrete ideas of how you perceive that activists can work on specific cases such as yours that would give momentum to working on dismantling the prison industrial complex?

Keith: I mean, we all talk about prison abolition and whatnot, but you can’t abolish prisons until you abolish the systems that make prisons necessary. We’re talking around the issue. It’s not really about the prisons. It’s about the systems that make these things necessary. It’s not about poverty. It’s about the system that makes poverty inevitable.

Of course I think we could come together, not just around my case – but we could use my case as a focal point if need be. But as I started off saying, this is much bigger than me. I don’t want to duplicate what Troy Davis did. I don’t want to have people think that everything is OK, not even a little bit OK, and that I’m somehow, you know, at peace with what is going on in my life.

So this book is not just a book; it’s my life. If you’re a part of this struggle, if you’re a part of this push to turn things around, then let’s fight these people together. Yes, some of us are going to die in the process. Yes, some of us are going to be hurt in the process. But since it’s inevitable that we’re going to come to these ends anyway, then let’s do something so that we can have a righteous life.

That’s what I’m saying, that’s what I’m trying to get out to activists or any ordinary, average citizens who might be listening to this message right now. Turn the TV off. Understand the reality that you’re dealing with. Find a group or organization that’s involved in eradicating this system and join them. That’s what it’s about.

Become an activist. Get off your ass and get into the fight. That’s what it’s about. I’m just saying, there’s always going to be another Troy Davis. Before Troy Davis, there was Emmitt Till. Before Emmett Till, there was somebody else. It’s going to continue to be this way.

The question is: How long are we going to sit back and accept this shit? How many more people need to die? I’ve got a little nephew who’s 6 years old. I want to do something before this shit gets to him. I’ve got a little friend named Daniel who’s just turning 10 years old. I’ve got other, I’ve got these little, young people and we’re turning this world over to them.

So let’s give them something that’s worth living for. That’s my whole thing that I’m trying to do with my life. I’m trying to make my life mean something. I’m not afraid by this death. That ain’t even the thing that’s driving me, motivating me. I just want to do something righteous with my life.

Let’s fight this thing together. Let’s come together. As I said, people are dying who could be saved if we just start caring about each other. That’s the only thing that is required – that we give a damn about each other.

Speaking of which, there’s a young friend there in Canada named Nicole Kish. What’s the status of her situation, if you know?

Dee: She’s still in the joint.

Keith: I was just going to send Nicole a shout out and tell her to hold on and keep her strength and keep her faith. Don’t give up the fight. She’s a beautiful young lady who lost her life, basically, at 21 years old. Just hold on. Just let her know people are thinking about her. She’s a beautiful poet, a beautiful writer, a beautiful person. Somebody send her some love so she can understand that she’s not in that situation by herself.

Dee: So thank you for speaking with me today and I hope that the next time we speak, well, who knows, maybe it might be under better circumstances.

Keith: Right, right, right. Exactly. That’s my hope. It was good to talk to you. Thank you for the opportunity. I appreciate you helping to publicize my plight. It really means a lot to me. Thanks a lot. I hope we can do it again sometime.

Dee: You’ve been listening to the voice of Bomani Shakur, also known as Keith LaMar, and he was speaking to us from death row at the Ohio State Penitentiary. LaMar is the author of “Condemned,” a first-hand account of his experiences during and as a result of the Lucasville Prison Uprising of 1993.

“Condemned” was published in 2014. You can purchase a copy of this book at amazon.com. If you want to also learn more about this case, go to keithlamar.org or justiceforlucasvilleprisoners.wordpress.com. Bomani also gave a shout out to Nicole Kish, also known as Nyki Kish, a wrongfully convicted woman in Canada, who is incarcerated in the Grand Valley Institution for Women, a federal prison in the province of Ontario. To learn more about Nikki’s case, go to freenyki.org.

Send our brother some love and light: Keith LaMar (Bomani Shakur), 317-117, P.O. Box 1436, Youngstown OH 44501.

Store

Store