by Malaika Kambon

The daguerreotype was an early type of photograph finalized and marketed by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) Daguerre, considered by France to be the leading scene designer in Paris, became successful with his trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) theatrical effects.

By opening a 350-seat diorama, in 1822 he proved himself to be the master of illusion. His theatrical effects were popular in fact because they were based upon a lie. Audiences thought they saw a real subject. The reality was the subject as two-dimensional painted scenes, represented on translucent linen and portrayed in a dark chamber.

This seems to have been one of the forerunners of modern day cinematography, sans popcorn. Daguerre later built a 200-seat diorama in London capable of pivoting viewers from scene to scene!

Photography, therefore, was a natural progression for him. He’d already exposed the public to theatrical sleight of hand, fostering a dependency on illusion to enhance their visual perceptions. Capitalistic expansion and its laws of supply and demand did the rest. The public began clamoring for automatic photographic reproductions based upon light and optics – indeed the very finest tools for magic and the science of optical illusion.

Usher in Daguerre’s daguerreotype photographic process in 1839. Unlike modern photography, there was no negative. The process involved images that were exposed directly onto silver, mirror polished surfaces, after exposure first to iodine vapor, then, as an “improvement,” bromine vapor, and finally housed in a velvet-lined folding case. They were then developed using mercury vapor, an unknowingly dangerous and unhealthy process.

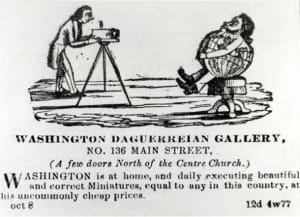

Augustus Washington was an Afrikan daguerreotypist, abolitionist and educator, as well as “one of the most talented and successful photographers in mid-1800s Connecticut.”

He learned the process of daguerreotype to help finance his studies at Dartmouth University, though, according to Mary Muller, lead museum educator at the Connecticut Historical Society, “his work depicts people of different classes and cultures, but ironically no portraits of African-Americans survived his years in Hartford.”

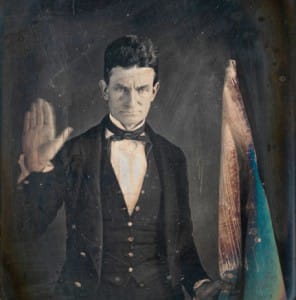

One of his most famous photos was a quarter plate daguerreotype, thought to be the first ever of abolitionist John Brown, who had from childhood sworn “an eternal war with slavery.”

Brown, already an abolitionist in 1846, increased his activism while still a wool broker in Springfield, Massachusetts, by frequenting anti-slavery meetings, avidly reading abolitionist literature and becoming well acquainted with many free Blacks in residence in near proximity to him.

He would become famous as the anathema of the South who led the Pottowatomie Massacre, which saw the execution of five pro-slavery Kansans, and the freedom fighter of the North, who led the disastrous raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry Virginia, beginning on Oct. 16, 1859.

Brown’s first photographic likeness, which was created by Washington roughly 13 years before Brown’s execution on Dec. 2, 1859, is one of the supreme ironies of history. Said irony catapulted old (dis)honest Abe Lincoln and the secessionist movement into the U.S. Civil War.

It was a very formal and intense photograph, described by the National Photographic Gallery of the Smithsonian Institute’s curator of photographs, Ann Shumard, to be “one of the treasures of the collection in all media. To have Brown daguerreotyped by an African-American is extraordinary.”

Noting the striking symbolism in Washington’s photo of Brown, African-American photo-historian Deborah Willis notes: “Brown’s pose next to a flag with his hand raised ‘as if he was being sworn into service, represents the abolitionist as a passionate young crusader for justice.’”

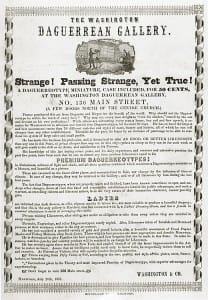

The photograph is atypical of the time period in which it was created, because a) African-American Washington’s studio would outlast those of his early business rivals, b) Washington, described as “an artist of fine taste and perception,” attracted the patronage of a broad range of customers by “offering both competitive prices and an extensive selection of cases, frames, bracelets, lockets and rings in which to house his “beautiful and correct miniatures,” c) Daguerre’s initial exposure times of 10-20 minutes, as seen in his “View of Boulevard du Temple,” had dramatically decreased to only a few seconds – while increasing exposure to hazardous conditions and materials and d) Washington took the time to publish a very detailed handbill of his studio, his work process and what the potential client could expect.

Among other advice, such as what to wear and why, Washington’s handbill advertised “Portraits, Engravings, and other Daguerreotypes, neatly copied.” (See also Washington Gallery daguerreotype case.)

The photograph of John Brown is thought to have survived only because the casing in which it was housed survived intact as well.

Many Afrikan people – Jules Lion and James Presley Ball, to name but two – braved the same racism and financial concerns as Washington to establish fine daguerreotype studios.

Washington’s studio closed only seven years after it opened so that he and his family could immigrate to Liberia. There he re-opened his business and prospered until his death in 1875.

Both John Brown and Augustus Washington have lived on, one perhaps more famously than the other, due to the very racism that both so avidly fought. “John Brown’s Body,” which tells the story of both the raid on Harper’s Ferry and the story of the Civil War the raid inspired, is an epic poem by Stephen Vincent Benet.

There was also an American marching song, known originally as “John Brown’s Song.” It was popular in the Union North during the Civil War. James E. Greenleaf, C.S. Hall and C.B. Marsh wrote the lyrics in 1861. William Steffe wrote the music in 1856.

The name of Augustus Washington is less a household word perhaps than that of his famous client. Washington, though a successful entrepreneur, believed that Afrikan people could not “develop (their) moral and intellectual capacities as a distinct people” in the United States, and so he and his family left for Afrika in 1853.

But his name is no less revered among those of us who actively look for Afrikan history that has been forcibly and deliberately omitted from global history books, as though Afrikan global history began with our enslavement.

We know that this is not true. So our fight for liberation continues.

Malaika H Kambon is a freelance, multi-award winning photojournalist and owner of People’s Eye Photography. She is also an Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) state and national champion in Tae Kwon Do from 2007-2012. She can be reached at kambonrb@pacbell.net.