by Malaika H Kambon

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of the play, “King Hedley II,” is its capacity for despair overlaid by an almost cynical dependence upon spiritual deliverance.

It is also about the revolt of the common man.

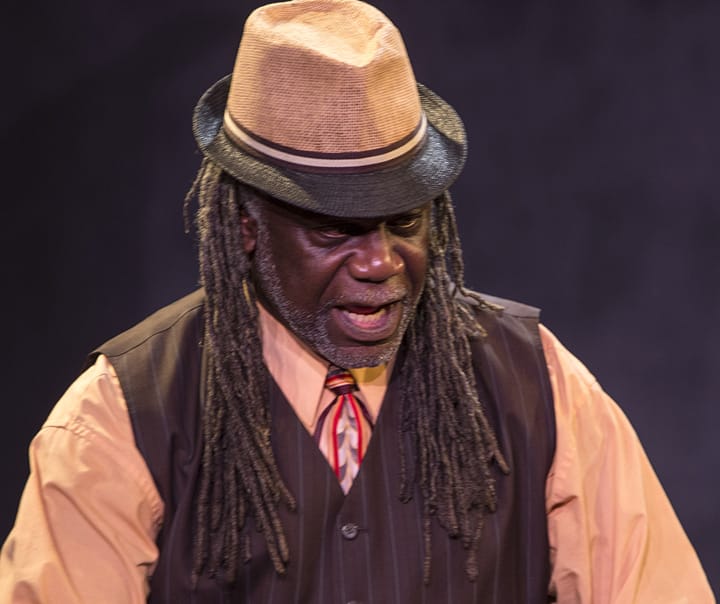

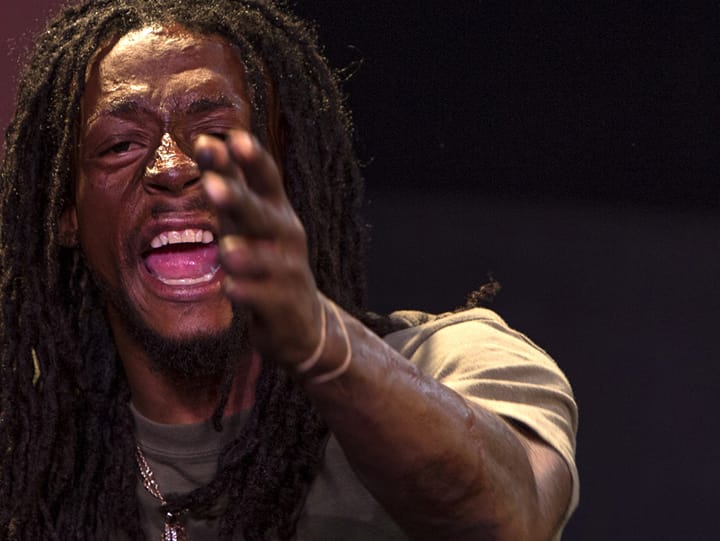

Directed and performed by Dr. Ayodele Nzinga and The Lower Bottom Playaz, Inc., “King Hedley II” is the ninth of the late Afrikan playwright August Wilson’s American Century Cycle, a 10-play docudrama of Afrikan life in the U.S. during the 20th century.

And The Lower Bottom Playaz, an all Afrikan theatre company, are on their way to an historic achievement: that of performing the American Century Cycle of August Wilson in its entirety, a feat unparalleled in world history. It hasn’t ever been done.

This is not an easy play.

The play has a ‘40s feel to it, even though it was set in the ‘80s, 1985 precisely – well after the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, Medger Evers and Fred Hampton and after the decimation of the Black Panther Party by Cointelpro and J. Edgar Hoover.

But this entire play is a metaphor.

It is self-sufficiency, self-defense and self-determination.

It’s the one good suit you take to the pawn shop every week, the fight for a better life that you fear to conceive, the advance that sells your soul to the company store, the legend of Sisyphus given Reaganomics – thy name is despair, the woman on welfare whose neighbors hate her and threaten her because she feeds cats and they think she’s rich.

It is the amen corner at the bottom of the food chain.

Yet everything in this play connects to something significant. Every piece reaches back in history and connects to now. Every piece of this play says that Black Lives Matter – and always have.

King Hedley’s insistence that the dirt for his plants is indeed “good dirt” resonates against stereotypes like “good hair,” the “good life,” “good clothes,” a “good man.”

And does Tonya’s choice of abortion over birthing a child into the depressive maw of Reaganomics cast her as enslaved, as a daughter of Ancestors who refused to conceive, killed newborn babies or jumped into shark-infested waters during the Middle Passage in rebellion against the terrorism of enslavement? Or does it speak more to her being a woman working a 9-5 (albeit slave) job who doesn’t want to have a baby with a man who seems headed back to jail?

Is the gun battle ending of this play a Door of No Return? Or a cleaning of the family closets?

It seems as though the seeds of organized political rebellion never reached the 1985 Hill District of August Wilson’s Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, or that the community was devoid of information concerning organized political resistance. Hence, we see the characters’ collective and individual despair.

Yet each of the six characters in the play, in the process of “looking for a better life,” devised ways within their means to attain such. The King (who clearly loves Tonya) and his partner Mister sold stolen refrigerators to acquire $10,000 to open a video store. Ruby was a retired blues singer, who is now fighting to keep her home – and considering if she wants to keep her wandering man.

Tonya worked a 9-5 and isn’t at all sure about keeping King. Elmore gambled – and won – in his own fashion. Aunt Ester spent 366 years as “a washer of souls.” Stool Pigeon believed himself to be oracular, and he probably is.

There are guns, a machete, violence, spirituality, family secrets, almost a wedding, and murder in this play.

Who knows what would have happened had the NAACP, Deacons for Defense, the Black Panther Party, Southern Christian Leadership Council, SNCC or the Nation of Islam strolled into town?

But the flip side is who knows what strength and leadership would arise from the six people of the Hill District of Pittsburg, circa 1985? Who knows?

August Wilson doesn’t say. He doesn’t write “King Hedley II” outside of the occupations or the time period of his characters. Nor, it seems, does he write political plays. Or does he?

He used theatre in “King Hedley II” as the power to bring the Afrikan community together to witness itself – where it was in that time period, and where it might go.

Did the influences of Malcolm X, Black Power, Romare Bearden’s collages and the Nation of Islam upon Mr. Wilson’s life’s work as a thespian allow him enough analysis of Afrikan life to be able to write his American Cycle Series with clarity, staying in the time periods of the cycle, through 10 plays?

This reporter believes yes. Did he stay within the 1985 time period with “King Hedley II”? Yes, he did.

Especially since “King Hedley II” begins with the physical transition of a 366-year-old Afrikan matriarch who is a spiritual healer and much beloved community leader – whom one of his characters, Stool Pigeon, is convinced will return. And he is determined to assist her resurrection with faith, a proper burial of her cat in King Hedley’s “good dirt,” and the blood of a mammal of significant size.

So the Matriarch is gone, but not dead, just as certain aspects of Afrikan history and community have been erased, re-written to falsehood from the Afrikan Motherland but are now corrected and re-birthed – i.e. no longer gone, and not dead.

“King Hedley II” isn’t art for art’s sake. This is living, grassroots, politically historic theatre, circa 1985.

So. This play is a metaphor. The Lower Bottom Playaz delivered a riveting performance.

Come see it.

The remaining performances are on First Friday, Sept. 4, 2015, at 8 p.m.; Saturday, Sept. 5, at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m.; and Sunday’s finale at a 2 p.m. matinee performance – all at The Flight Deck, 1540 on Oakland’s Broadway.

Malaika H Kambon is a freelance, multi-award winning photojournalist and owner of People’s Eye Photography. She is also an Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) state and national champion in Tae Kwon Do from 2007-2012. She can be reached at kambonrb@pacbell.net.