The trial is on! since Monday, Nov. 9, probably concluding Friday, Nov. 20, in Courtroom 4, 17th floor of the Federal Building, 450 Golden Gate Ave., San Francisco – no court on Thursday

U.S. District Court: Claims of a false disciplinary report, unnecessary confiscation of materials and disparaging statements made during destructive cell search subject guards to trial.

by Jesse Perez

Pelican Bay State Prison guards named in a civil rights lawsuit by a prisoner activist held in solitary confinement for over a decade are defending against alleged retaliatory and malicious conduct aimed at retaining the prisoner plaintiff in conditions of isolation before a federal jury, U.S. District Court Judge Vince Chhabria of San Francisco ruled in late September.

In my civil rights suit, I have alleged that the guard defendants retaliated and conspired to retaliate against me after learning of my success in a separate suit challenging my unlawful placement in solitary at Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit, my participation in hunger strikes and my writing of articles critical of prison officials’ solitary confinement policies.

According to the Section 1983 complaint filed in court on Oct. 10, 2012 – just days after I obtained a settlement in another suit that contemplated my release from solitary and damages – the guard defendants approached my cell, ordered me to strip naked, subjected me to unclothed visual inspection and, after I was allowed to dress in boxer shorts and sandals, removed me and my cellmate, Rudy Guerrero, from the cell while in handcuffs.

The guards then performed a destructive search of our cell, confiscating my personal property. One guard defendant was overheard by a prisoner witness as disparagingly remarking, “These knuckleheads should file lawsuits more often, makes this job a whole lot more rewarding” – the quip interspersed with laughter from another guard assisting in the search.

The court’s September ruling also noted that depositional testimony indicated that one guard defendant asked Guerrero if he was “into filing lawsuits too.” After he answered, “No,” the guard defendant replied: “Good for you. Keep it that way.”

In my own deposition, the court observed, I testified that I asked Anthony Gates, another guard defendant, for the timely return of my paperwork and notified the guard of my pending litigation, to which Gates responded: “Oh yeah, about that – you might’ve been able to collect from us, but get comfortable because we’re gonna make sure you stay [in solitary] where you belong. And as for your property, don’t worry; we’ll get it to you by tomorrow or so.”

“Oh yeah, about that – you might’ve been able to collect from us, but get comfortable because we’re gonna make sure you stay [in solitary] where you belong.”

The record before the court supported my claim that the guards made good on both accounts.

On Oct. 11, 2012, my property was returned. But, among other items, important legal documents were missing as well as working drafts and completed copies of articles I authored that are critical of the state prison system’s policies on indefinite solitary confinement.

Ten days later, on Oct. 21, 2012, I received a disciplinary report issued by defendant Gates. The report charged me with “willfully resisting, obstructing a Peace Officer,” an offense made on factual allegations that, if found guilty, defendants’ pleading papers admit, would have required that I remain in solitary under newly implemented SHU placement policies.

Gates specifically accused me of obstructing the guards’ view into the cell during the Oct. 10 search, purportedly to conceal Guerrero’s alleged destruction of gang paraphernalia. Other guard defendants gave conflicting reports about what actually happened in their own depositions.

And the court also considered that the record reflected my success in defending against the charge in an internal disciplinary hearing by pointing to the physical impossibility of obstructing the guards’ view, given the layout of the cell. The hearing officer, Judd Anderson, agreed with me, found me not guilty of both the charged and lesser included offense, and ultimately dismissed the meritless disciplinary report.

“There is … evidence from which a reasonable juror could conclude that the defendants were retaliating against Perez for his prior lawsuit when they trashed his cell, took his papers and issued a false [disciplinary report] against him,” wrote Judge Chhabria in his order denying defendants’ summary judgment. In the same order, and given the factual tension in the record, the court also rejected the affirmative defenses asserted by defendants.

“There is … evidence from which a reasonable juror could conclude that the defendants were retaliating against Perez for his prior lawsuit when they trashed his cell, took his papers and issued a false [disciplinary report] against him,” wrote Judge Chhabria in his order denying defendants summary judgment.

Consequently, the court’s September ruling cleared the way for trial – slated for late November 2015.

We arrive at this trial on the crest of this incredible wave, at a moment following the unanimous vote earlier this year by the U.N. Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice to approve the Mandela Rules, which prohibit indefinite and prolonged solitary confinement – defined as more than 15 consecutive days; the decision of both the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society of Canada to jointly sue the Canadian government over its use of solitary confinement in the country’s prisons in January; President Obama’s own criticism of the practice as “not smart,” expressed while addressing the NAACP in July; and Justice Kennedy’s urging that such correctional practice “ought not to be the result of society’s simple unawareness or indifference.”

This flurry of social activity is what is meant when the High Court references society’s evolving standards of decency in its Eighth Amendment jurisprudence.

In the wake of the landmark settlement in the class action Ashker v. Brown, this more humane trend in corrections is increasingly important in the prison reform movement – particularly because confinement to solitary in California will now depend solely on true (or false) findings that the prisoner’s behavior justifies it.

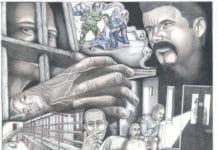

As prisoner activists seeking to make positive contributions in the interest and human dignity of prisoners, we understand that the trappings of power enjoyed by guards represent the biggest obstacle to significant and lasting progress. We look forward to the opportunity to shine a public light at trial and rein in what prisoner activists often endure in exercising their constitutional rights: the retaliatory abuse of the department’s disciplinary process by prison guards.

As prisoner activists seeking to make positive contributions in the interest and human dignity of prisoners, we understand that the trappings of power enjoyed by guards represent the biggest obstacle to significant and lasting progress. We look forward to the opportunity to shine a public light at trial and rein in what prisoner activists often endure in exercising their constitutional rights: the retaliatory abuse of the department’s disciplinary process by prison guards.

The prisoner plaintiff is ably represented by attorneys with Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP, who were not available for comment in this story.

Send our brother some love and light: Jesse Perez, K-42186, PBSP SHU A5-106, P.O. Box 7500, Crescent City CA 95532. Read these stories by Jesse Perez previously published by the Bay View:

- “Building prisoners’ political power”

- “Prisoner Political Action Committee update: In solidarity, we can win”

- “‘I contribute to peace,’ a pledge to end hostilities inside and out”

Store

Store