by Robyn C. Spencer

Fascism has been thrust into the mainstream political vocabulary of the United States since the election of President Donald Trump on a platform grounded in xenophobia, corporate dominance and right wing white nationalism. After the election, search engines and online dictionaries reported a dramatic increase in users seeking to define the term.

News outlets from Al Jazeera (“The Foul Stench of Fascism in the Air”) to Forbes (“Yes, a Trump presidency would bring fascism to America”) to the Washington Post (“Donald Trump is actually a fascist”) published articles analyzing how Trump fits into fascist paradigms. Most recently, The Nation (“Anti-Fascists Will Fight Trump’s Fascism in the Streets”) chronicled the long history of anti-fascist organizing in Europe and the United States to inspire activists engaged in resistance at this political moment.

Black history has been marginalized in this burgeoning contemporary discourse about fascism. Analyses of the U.S. as fascist have a long history in the Black intellectual tradition. Black thinkers like Harry Hayward, Claudia Jones, George Jackson and Kuwasi Balagoon used fascism as an analytical framework to understand the rise of segregation in the South after Reconstruction; white populism at the turn of the 19th century; land and labor struggles in the Black Belt South, and the evolution of capitalism in the 1970s.

The Black Panther Party played a prominent role in the modern history of Black anti-fascism. Panther leaders were deeply influenced by “The United Front Against Fascism,” a report by Georgi Dimitroff delivered at the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in July-August 1935.

Black history has been marginalized in this burgeoning contemporary discourse about fascism.

By 1969, the Panthers began to use fascism as a theoretical framework to critique the U.S. political economy. They defined fascism as “the power of finance capital” which “manifests itself not only as banks, trusts and monopolies but also as the human property of FINANCE CAPITAL – the avaricious businessman, the demagogic politician and the racist pig cop.”

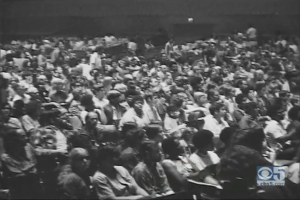

In July 1969, close to 5,000 activists from organizations like the Black Student Union, Communist Party USA, Los Siete de la Raza, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Students for a Democratic Society, Third World Liberation Front, Young Lords, Young Patriots, Youth Against War and Fascism and the Progressive Labor Party flocked to Oakland, California’s Municipal Auditorium in response to the Black Panther Party’s call for allies to gather and strategize against fascist conditions in the United States.

This United Front Against Fascism (UFAF) conference was an important moment in the history of the Black Freedom movement and the New Left. The Panthers hoped to create a “national force” with a “common revolutionary ideology and political program which answers the basic desires and needs of all people in fascist, capitalist, racist America.” At the opening session, Seale called for unity of action, arguing that “we will not be free until Brown, Red, Yellow, Black and all other peoples of color are unchained.”

On the first day of the UFAF, Panther leaders, activist professors, movement lawyers, labor activists, radical politicians and others addressed the crowd in the large auditorium until midnight. The second day was organized into workshops on fascism and women, workers, students, political prisoners, political freedom, health and religion.

This United Front Against Fascism (UFAF) conference was an important moment in the history of the Black Freedom movement and the New Left.

Vigorous debates erupted between conference attendees over Marxist theory; the “male showmanship” of some speakers; the structure of the conference; and the implications of community control of the police. Some of the most provocative discourse at the UFAF came out of the women’s workshop, where Panther women discussed male supremacy as a reflection of capitalism and argued that “there cannot be a successful struggle against fascism unless there is a broad front and women are drawn into it.”

The role of state repression in stifling dissent was a central theme and many speakers touched on the issue of political prisoners as evidence of the operation of fascism in the United States. The Panthers, under heavy infiltration and attack by the FBI’s counterintelligence program by this time, positioned combatting state violence as the core of anti-fascist organizing.

This orientation was evident on the last day of the conference, which was devoted to the Panthers’ detailed plan to decentralize police forces nationwide. They proposed amending city charters to establish autonomous community based police departments for every city, which would be accountable to local neighborhood police control councils comprised of 15 elected community members. They launched the National Committees to Combat Fascism (NCCF), a multiracial nationwide network, to organize for community control of the police.

The role of state repression in stifling dissent was a central theme and many speakers touched on the issue of political prisoners as evidence of the operation of fascism in the United States.

After the conference, inquiries about starting NCCF chapters flooded into Oakland from Salt Lake City, Utah; Albany, New York; Las Vegas, Nevada; Toledo, Ohio; Sunflower, Mississippi; Keatchie, Louisiana; Erie, Pennsylvania; Richmond, Virginia; St. Louis, Missouri; and Austin, Texas. The NCCFs offered a multiracial group of local activists around the country a new avenue of involvement in Black Power politics at a time when the Panthers had launched purges and membership freezes to combat infiltration from COINTELPRO.

By April 1970, the FBI recorded 18-22 NCCFs around the country. The story of these NCCF chapters is best seen in local BPP history.

It is unclear to what extent the NCCFs fueled an increased engagement with fascism at the grassroots level and how the solidarity politics of the United Front evolved over time. The conference solidified the Panthers’ alliance with the Los Siete Defense Committee.

The Aug. 16, 1969, issue of The Black Panther included “Basta Ya,” a newsletter in Spanish that was produced by Los Siete supporters which contained updates on the case and announced community programs initiated by the Defense Committee, such as a Panther inspired Breakfast for Children Program in the Mission District in San Francisco.

The rich potential of the Panthers efforts was derailed by COINTELPRO. Several FBI agents surveilled UFAF events. One agent, Thomas Edward Mosher, infiltrated the Panthers’ pre-conference planning structure, insinuating himself as a liaison between groups and attending meetings in leaders’ homes. Heavily infiltrated by FBI agents whose goal was to collect information, derail political action, foment violence and plant seeds of suspicion and decimated by raids and arrests of Panthers nationwide, the Panthers shifted gears.

In response to critics inside and outside of the BPP about the majority white attendance at the UFAF, the Panthers sought to find common ground with Black people who could “relate to the social practice of 400 years of brutality and murder perpetrated on us by the fathers of fascism,” yet felt alienated from the Panthers’ lexicon. The history of how the Panthers organized against fascism locally and nationally in Panther chapters and NCCF offshoots is essential at this political moment but remains elusive in both history and memory.

If the growing resistance movement to Trump’s fascism is to realize its potential for societal transformation, it must draw from the deep well of Black anti-fascist resistance.

In late January 2017, fascism remains in the top 1% of words searched in the US, according to Merriam-Webster, leading one news article to opine, “Americans Worried About Fascism.” Yet the UFAF’s Wikipedia page is two sentences long and does not even acknowledge that the Panthers were the main impetus behind the conference. The NCCFs don’t even have a Wikipedia page.

The history of the UFAF demonstrates that discussions about fascism in the U.S. are nothing new. It shifts the discussion of fascism away from an American exceptionalist terrain, where the U.S. is compared with Europe and government structures or despotic leaders are analyzed, and instead demonstrates the value of unearthing manifestations of fascism in the lived experiences of Black people in the U.S.

Perhaps most importantly, this brief glimpse into the UFAF’s history reveals the multiplicity of tactics that the Panthers used to combat fascism, including visual culture, political education and grassroots campaigns against state violence. If the growing resistance movement to Trump’s fascism is to realize its potential for societal transformation, it must draw from the deep well of Black anti-fascist resistance.

Robyn C. Spencer is a historian who focuses on Black social protest after World War II, urban and working-class radicalism, and gender. Author of the new book, “The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland,” she is associate professor of history at Lehman College and can be reached at robyn.spencer@lehman.cuny.edu or @racewomanist. You can pick up “The Revolution Has Come“ for 30% off using coupon code E16SPNCR, and you can read the book’s introduction here.