by Jonathan Michels

As the snowbirds arrived in Florida along with the mild January breezes, a small uprising of laborers who work under lock and key stopped production and made demands. This coordinated struggle was carried out by members of one of the most violently exploited groups in America: incarcerated workers.

Inmates at 17 Florida prisons launched the labor strike, calling themselves “Operation PUSH,” to demand higher wages and the reintroduction of parole incentives for specific groups of inmates. The striking prisoners argued that because they receive little to no pay for their labor, they are nothing more than modern-day slaves under the 13th Amendment, which prohibits slavery and indentured servitude except as punishment for the conviction of a crime.

By refusing to cook, clean and generally maintain the prison facilities, the incarcerated workers aimed to put aside their differences and work together, to leverage their labor against corrections officials until they caved in to their demands. “This is our chance to establish UNITY and SOLIDARITY,” prisoner organizers proclaimed.

Inmates at 17 Florida prisons launched the labor strike, calling themselves “Operation PUSH,” to demand higher wages and the reintroduction of parole incentives for specific groups of inmates.

Operation PUSH is just the latest action in a growing movement to organize inmates and, for some, to abolish the prison system altogether. In order to maintain the pressure, incarcerated workers and allies have already called for more direct actions on June 19th, the annual holiday to commemorate the abolition of slavery and more commonly referred to as Juneteenth.

Prisoners and allies have also announced another wave of strike actions set to begin later this summer on Aug. 21.

Prisoners who choose to take part in collective action do so at great risk to themselves and others. In the wake of the Florida strike, reports trickled out about how corrections officials meted out a range of disciplinary actions against the striking inmates, including placing them in solitary confinement, restricting their communication and transferring them to facilities further away from their loved ones.

Operation PUSH is just the latest action in a growing movement to organize inmates and, for some, to abolish the prison system altogether.

Today’s inmate organizing has a powerful precedent. During the early 1970s, the prisoners’ union movement counted tens of thousands of members in prisons from California to North Carolina. This activism was inspired by Black Power organizing as well as decades of agitation by both Black and white prisoners to expand their legal rights.

But there was one Southern inmate union in particular, in the least unionized state in the country, that forced legal battles about whether prisoners have the right to free speech and assembly.

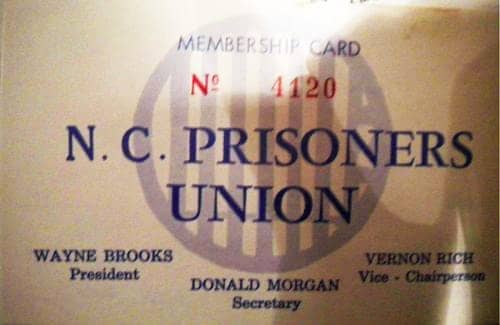

At its height in the early 1970s, the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union collected union cards from more than 5,000 prisoners, roughly half of the state’s total inmate population. The union’s board of directors stressed interracial solidarity and organized across racial lines, with Blacks, Lumbee Indians and whites working together to demand change.

Their calls for collective bargaining rights, higher wages and a larger voice in the grievance process pitted union members against corrections officials in a legal showdown for institutional control.

The struggle to expand prisoners’ rights to free speech and assembly received a heavy blow with the 1977 Supreme Court ruling in Jones v. The North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union.

At its height in the early 1970s, the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union collected union cards from more than 5,000 prisoners, roughly half of the state’s total inmate population.

While not explicitly banning labor unions in prisons, the Jones decision made it nearly impossible for prisoners to collectively organize behind bars. Even more deleterious, advocates say, was the Supreme Court’s institution of a “hands-off” doctrine when it comes to determining whether inmates’ First Amendment rights should be overruled in cases where the institutional safety of prisons is concerned, effectively ceding decision-making power back into the hands of prison administrators.

“Supreme Court justices tend to defer to corrections officials in prisoners’ rights cases,” said Amanda Hughett, a fellow at SUNY-Buffalo’s Baldy Center for Law & Social Policy who is currently writing a book about the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union.

“Jones bolstered that deference and it capped a moment when it was still uncertain how far prisoners’ rights would extend.”

The Jones decision all but ensured the demise of the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union and for a while, it seemed that this history was lost. However, during the last decade, largely as a result of growing awareness about mass incarceration, and political organizing that identifies with prison abolition, there has been renewed scholarly interest in prisoner activism.

Over the course of several months, I spoke to three North Carolina veterans of the prisoners’ union struggle. NCPLU organizers Robbie Purner and Chuck Eppinette worked diligently from the outside to support incarcerated worker resistance.

Meanwhile, prisoner Jim Grant organized on the cell block. All three were irrevocably marked by the experience.

Although the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union was defeated by the U.S. Supreme Court decision more than 40 years ago, these interviews describe a time in North Carolina when prisoners found hope in solidarity. As the next national prison strike approaches, they may do so again.

Interview with Jim Grant of the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union

Introduction: After receiving his PhD in organic chemistry from Pennsylvania State University, Jim Grant traveled south for a short stint with Volunteers In Service to America, or VISTA, the domestic version of the Peace Corps, working mainly in communities of color. Grant continued to strengthen his ties with social justice organizations as a correspondent for African-American publications like The Southern Patriot.

Later, he and two other African-American men garnered national attention when they were accused of setting fire to a riding stable near Charlotte. Although he consistently maintained his innocence, Grant received a 25-year sentence for the deadly blaze.

North Carolina Gov. Jim Hunt later commuted Grant’s sentence, but only after the men were thrust into the center of an international advocacy campaign. The struggle recalled similar efforts during the first half of the 20th century, which fought for Black Southerners charged under dubious circumstances that critics called “legal lynchings.”

The case of the “Charlotte Three” became a cause célèbre among some of the most prominent social justice activists of the day, including Angela Davis and James Baldwin, and for the first time in the organization’s history, Amnesty International designated the self-effacing Grant and his friends political prisoners.

While protesters marched in the streets for Grant’s release, he continued to agitate for change on the cell block as a union organizer with the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union.

The following is an edited transcript of my interview with Grant in January 2018.

Excerpted transcription from interview with Jim Grant

In 1975, I got involved in the prisoners’ labor union after I was sent from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. My feeling was that you try and organize wherever you happen to be.

I met Wayne [Brooks] and Donald Morgan but I didn’t know them originally. I came in late. They had already started the prisoners’ labor union when I got here from Atlanta. Don was the one who was always in his books. Wayne not so much. Wayne was more into talking with the prisoners like I was.

There were a lot of different things that needed to be dealt with by the Department of Corrections that weren’t being dealt with. We weren’t talking about immediate parole or anything of that nature. We were talking about everyday issues.

We felt that we should be the ones to make decisions about those types of things.

One of the issues up there at the camp in Newland was related to the fact that there were no guards who were either [Indigenous] or Black. It was an all-white guard force.

There were 35 Black [prisoners] and three Native Americans who were there at the camp in Newland. Everybody else was white. There was no one up there that we could speak with. We said that we wanted somebody that we could talk to who was familiar with us and familiar with our way of living.

They had people working in the fields. Why not pay them so they can take care of their families? Everyone was saying these folks are on welfare. Okay, well get them off of welfare. Put them to work. We’d be glad to work. But pay them a decent wage.

A lot of the guys in prison, a lot of them don’t know how to read. We tried to help those who couldn’t read and who wanted help with contacting their family.

We had a couple of sit-ins in the different camps about food. The food was not fit and it needed to be improved. That came to pass.

Some of the guys didn’t want to get involved with it because they said that would hurt their parole chances. They sent some of them to the hole for joining. At least that’s what we think the reason was.

Some of them didn’t give a damn. They went ahead and joined anyway. It was worth it to me. I didn’t give a damn too much about parole issues or anything of that nature. But I’m only one person. I’m not going to be able to move around and take this issue into my hands and run with it.

I’m more of a teacher type of person. I’ll teach you and try and see that you know enough to take things on. It gives the other person the fact that they have to carry the ball. It makes them more willing to step out if they’re given the ball to carry.

It wasn’t easy to contact other union members. If you wanted to contact Donald Morgan, you wouldn’t know where the hell to find him. We worked through Robbie and Chuck.

They were the ones who were able to maintain some level of coherency between the members. We were scattered all over the place. You never know where the hell they are. They were the only ones that would let us know. They would keep things rolling. And any of the legal stuff was totally in their hands.

I still think that the union should have happened. I don’t see people coming to the same conclusion like they did in 1975 but I think that people are not going to continue to put up with prisons as they are now.

The fact that you were able to at least get somebody to even think of making a move like that has to be looked at with some level of hope.

I can’t do damn near as much as I used to be able to. But the younger ones need to really understand that if they continue to push forward, they might be able to get something done.

One thing we need to understand is just because people end up going to prison for one reason or another doesn’t mean you need to give up your right to be able to speak out and stand up for what you believe in. Your everyday issues. That you don’t give up those things.

I think a lot of those folks probably shouldn’t even be in prison. What they have to say both in the way in which they look at the conditions inside as well as the whole issue of prison as a way of keeping people in their place. Maybe that’s not the way to do it.

‘Prisoners’ organizations were thought to be dangerous’: Conversations with organizers of the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union

“People were afraid of prisoners’ organizations. People had Attica on their mind. Prisoners’ organizations were thought to be dangerous.” – Interview with Chuck Eppinette of the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union

Earlier this year, Florida prison inmates took part in a statewide labor strike to protest forced labor that they view as a modern form of slavery. The strike was just the latest action in a growing movement to organize inmates and for some, to abolish the prison system altogether. In order to maintain the pressure, incarcerated workers have also announced another wave of strike actions set to begin later this summer on Aug. 21.

Today, we present the remarks of Chuck Eppinette, an NCPLU organizer who worked diligently from the outside to support incarcerated worker resistance.

Introduction: As the son of a Marine, Chuck Eppinette grew up under the military’s strict social order in which even a simple exercise like choosing a seat at the movie theater was conducted under the gaze of the Military Police. Eppinette later became radicalized by the leftist politics of the late 1960s as a student at North Carolina State University where he joined the anti-war movement.

In 1970, 2,400 inmates at California’s Folsom Prison initiated a 19-day work strike and demanded the right of prisoners to form or join labor unions. Out of this struggle, the prison union movement was born.

“For the first time, inmates and ex-cons have forged themselves together throughout the country to organize for their own self-protection and to win the basic human rights ostensibly guaranteed every citizen by the Constitution,” wrote Frank Browning in Ramparts Magazine.

Eppinette first heard about the burgeoning prisoners’ union movement from another anti-war activist who was serving time out west. When FBI agents arrested Eppinette for draft resistance, he made preparations to unionize inmates behind bars. The way he saw it, social justice organizing needed to happen whether you were in the slammer or not.

Although his federal case was later dismissed, Eppinette continued to connect with prisoners like Wayne Brooks who were eager to unionize. By the time the members of the North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union filed for incorporation in 1974, Eppinette had become an indispensable part of the union’s outside support as a paralegal for Debbie Mailman, the union’s chief attorney. The following is an edited transcript of my interview with Eppinette in December 2017.

Excerpted transcription from interview with Chuck Eppinette

There had been a riot at Central Prison a year or two before and Attica had many in the social change movement thinking about what was going on in prisons. People were interested in prison reform. Not necessarily a prisoners’ union but they still saw some need for making changes.

Many liberals did not like the idea of a prisoners’ organization because they thought all it did was create power brokers within the prison that would cause problems as opposed to it being a way of having democratic solutions and input to addressing problems. There were a few “purest” Marxists I knew who thought working with prisoners was a waste of time because they were not the true proletariat.

But for the folks who were actually doing organizing, the union was exciting. The idea of this kind of grassroots organizing and workers’ control was very big. How could you not be excited about this?

If you want to find a place that is working-class, walk into a prison. There’s not a lot of rich folk there. Eugene Debs resonated with a lot of us. He spoke to that with “While there’s a soul in prison, I am not free.”

During this period, prisoners were pretty much at risk at all times for any complaints about things. You could write a letter to the editor if you were a prisoner saying things were horrible in here and you could end up in the hole. There was virtually no due process. The isolation cells were horrific and there later were a lot of lawsuits about them.

God bless the prison administration. They unwittingly helped grow the union a great deal because I think they were convinced it was a handful of people so they started transferring inmates to other units which was like sending organizers out.

They would transfer someone to another unit and suddenly we would get a lot of union cards from that unit and then they would transfer that person to another unit. We would get cards from that unit.

It speaks to how bad things were and how powerless people were. You would go, “Well, of course they would join the union.” But being powerless and subject to arbitrary punishment and things that greatly affected your life, the fact that they were willing to join the union, that they were willing to put their name down on something was incredibly impressive to me.

I don’t think prison administrators thought this was going to be that big of a deal. I think they were in a state of denial. Once they decided it was serious, they stopped the union newsletter from coming in. They wouldn’t let Robbie and I into a prison.

When the prison administration acted to shut down the union, we won the effort to defend the union’s rights before a three judge Federal District Court. But then the state appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

People were afraid of prisoners’ organizations. People had Attica on their mind. Prisoners’ organizations were thought to be dangerous.

Despite the odds, we always held out hope. There were some good people on the Supreme Court.

I don’t know if we were ready for as devastating a loss as it was. It was across the board: no. It was just over.

We all knew where the power was. That’s one of the things that made the union so incredible. The union getting crushed was always a possibility. And the stakes for the people in the union were huge. When it fell apart, there was anger at the system.

What we did was beat ourselves up a lot. If you’ve been involved in stuff that fails, you ask yourself, “What could I have done? How did we miss this?”

The Jones decision crushed the movement for prison workers’ organizations. It said the state gets to determine security issues and that’s how it is. The strategies for what can be done and what you should do changed. There was an era of some big prison-class lawsuits after because that was the only thing that could be done.

Changes have been made but the type of changes that need to be made can’t be made until there’s an organization within. That’s why unions are important. You can have the most well-meaning people on the outside of a factory writing labor laws but unless the people who are directly affected have a voice in what happens, then the type of change that needs to happen will never happen. The North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union showed a possibility.

Prisoners in a prison system that was statewide, more units than there are now that was Black and white, formed an organization that had these very specific political goals. And had the majority of the members of the prison system as members of that organization. As far as a possibility of what can be done, it’s an incredible example.

Jonathan Michels, multimedia journalist, can be reached at jonscottmichels@gmail.com. Visit his website: www.jonathanmichels.com.