by Wanda Sabir

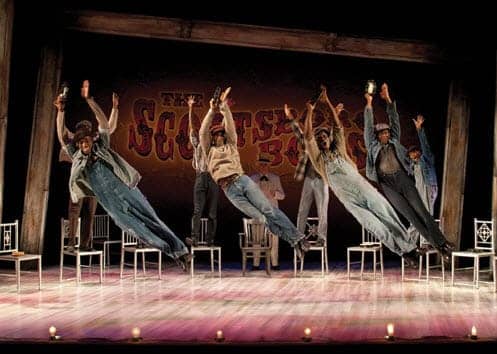

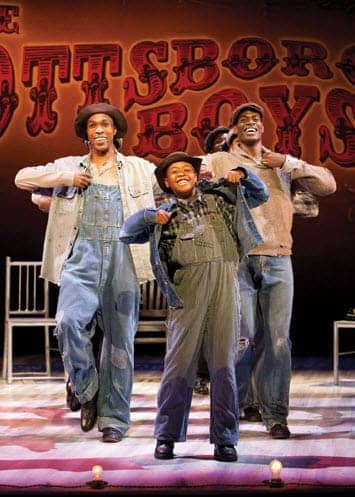

The parody currently on stage at American Conservatory Theater, “The Scottsboro Boys,” staged by director-choreographer Susan Stroman (“The Producers”), through July 22, 2012, takes a historic tragedy in American history and recasts it as buffoonery.

The parody currently on stage at American Conservatory Theater, “The Scottsboro Boys,” staged by director-choreographer Susan Stroman (“The Producers”), through July 22, 2012, takes a historic tragedy in American history and recasts it as buffoonery.

Black America should not be surprised. Classic guilt is always re-envisioned in this paradigm. The boogeyman is always Black and male. This is why to present the Scottsboro case as a vaudeville minstrel show with the actors in their natural skin is letting the criminal system masquerading as justice off the hook. In an election year with capital offence on the ballot in California, why aren’t current issues interrogated in this obvious overlap?

Why isn’t this case used as an opportunity to let audiences know that Scottsboro is still happening in America daily? Organizations like Legal Services for Prisoners With Children, California Prison Focus, Critical Resistance, Justice Now, Youth Outlook and the Ella Baker Center should be a part of the audience engagement conversations.

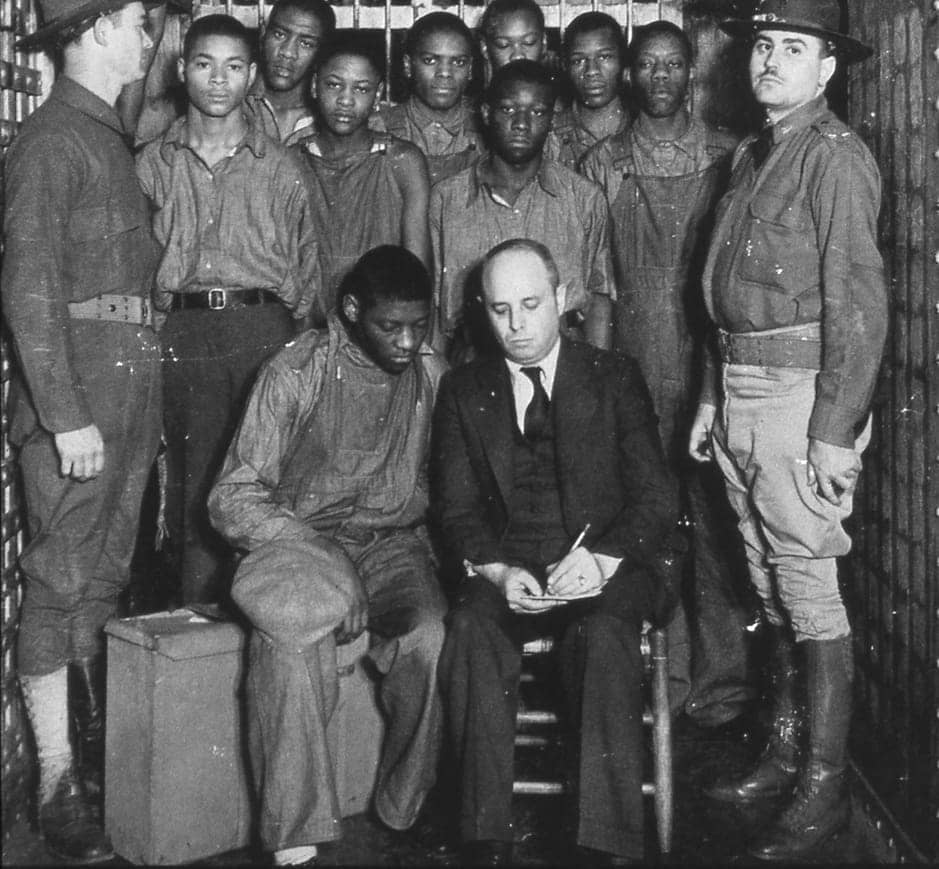

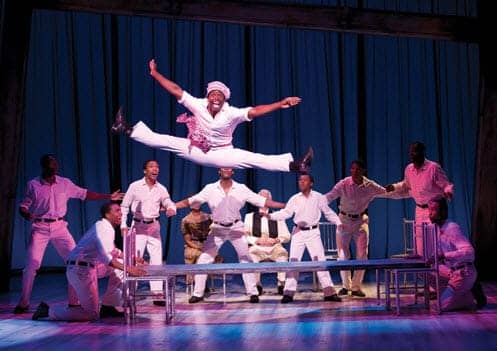

For the descendants of those nine men – David Bazemore as Olen Montgomery, Nile Bullock as Eugene Williams, Clifton Duncan as Haywood Patterson, Clifton Oliver as Charles Weems, Cornelius Bethea as Willie Roberson, Christopher James Culberson as Andy Wright, Eric Jackson as Clarence Norris, James T. Lane as Ozie Powell and Clinton Roane as Roy Wright, dancing and singing on stage – this is not a parody of life back then; it is life right now without the laugh tracks and colorful commercials.

“The Scottsboro Boys” shows two instances of resistance: one when Haywood escapes and the other when Ozie takes a pocket knife and puts it to the neck of a guard. The Boys are battered emotionally and then demeaned by the media over the course of the trial and incarceration. When Ozie says enough is enough to the prison guards transporting him and the other prisoners to yet another session in the kangaroo judicial sitcom, we applaud his gumption even if it costs him dearly given the violent overreaction.

“The Scottsboro Boys” shows two instances of resistance: one when Haywood escapes and the other when Ozie takes a pocket knife and puts it to the neck of a guard. The Boys are battered emotionally and then demeaned by the media over the course of the trial and incarceration. When Ozie says enough is enough to the prison guards transporting him and the other prisoners to yet another session in the kangaroo judicial sitcom, we applaud his gumption even if it costs him dearly given the violent overreaction.

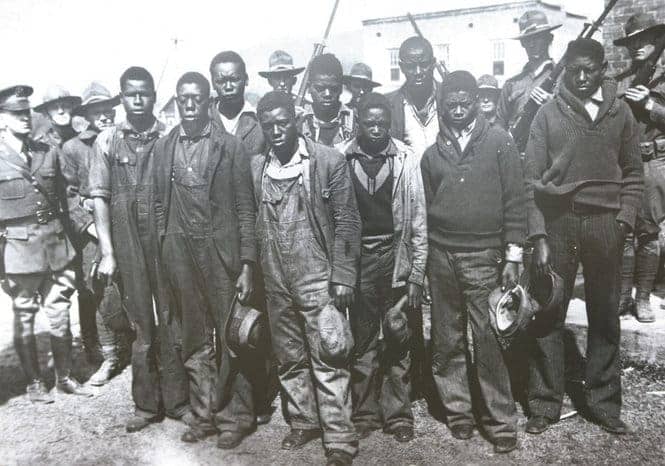

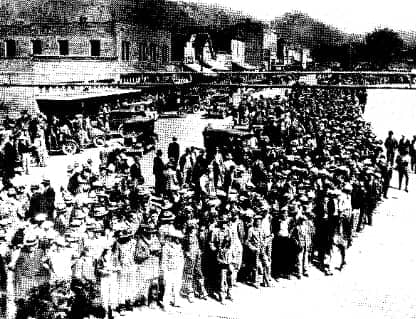

To date, when one reads about the Boys, one sees “low IQ,” “illiterate.” They are portrayed as pitiful specimens lacking the academic or educational acumen to be taken seriously, let alone justify their tragic lives. These youth are forward thinking enough to know that justice in Alabama or anywhere in the South is slim to none, so they board a train headed for opportunities so they can purchase human rights denied, like education and medical care, reading glasses, employment … and hit a wall. All accused of rape, the accusations or lies trap them like mice in a labyrinth this nation still tosses innocent youth into daily, California one of its larger game reserves.

While reading Waights Taylor Jr.’s “Our Southern Home: Scottsboro to Montgomery to Birmingham, the Transformation of the South in the Twentieth Century,” all I could think about was my Daddy wasn’t born yet, and then after the first trial and the second, he was; and by the time the Boys, now men, were acquitted, my Daddy was taking his first steps and he could talk.

Ozie Powell was paroled in June 1946. Haywood escaped from Atmore Prison Farm the summer of 1948 to Detroit to stay with his sister. When the FBI caught up with him Michigan, Gov. G. Mennen Williams refused to extradite Haywood, and eventually Alabama officials gave up. Unfortunately, Haywood, who is the hero in the Broadway version of the story, ends up back in prison on manslaughter charges, where he dies from cancer Aug. 24, 1952, at 39 (Taylor Jr., pages 233-234).

It is pretty amazing how John Kander and Fred Ebb, with book by David Thompson, are able to condense so much history into the extended work – performed without intermission. We move from boys hopping a train with the hope of bettering their financial circumstances to the false accusations from Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two poor white sex workers also looking to better their fortunes. This was the promise; however, for the nine young men, the train was not bound for glory.

The work leaves out the Black community support of the young men. I believe family members went on a speaking engagement in Northern cities like New York. I do not know why the African American presence is omitted. Much of the abridged account is supplemented by the Playbill and Notes on Plays, but not the entire story.

In the discussion after the show I attended, facilitated by Dr. Mason Turner, chief of psychiatry at UCSF, several patrons expressed displeasure with the form the story was told in. Called “On the Couch,” the discussion centered on the discomfort the majority white audience felt. I can only think about David Mamet’s “RACE,” a part of the theater’s last season, which was seen as hilarious when in fact it too was a tragedy.

In this case a Black woman is raped, the villain white and male and prosperous, the legal team about as diverse as they come. In speaking to Susan Heyward, who plays the new addition to the legal team, she speaks of her surprise when the audience laughs and wonders in a mixed audience who would laugh at what? Listen to the rebroadcast of the interview with commentary: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks/2011/11/04/wandas-picks.

“To Kill a Mockingbird,” the Pulitzer Prize winning novel published in 1960 by Harper Lee, is not a musical and the Black protagonist, Tom Robinson, also innocent of the rape charge, is lynched after he is found guilty despite evidence to the contrary.

The problem at the trials’ end is the Boys’ black faces. In the paradigm where the Scottsboro Boys live socially, justice is blinded by their blackness. Eighty-one years later, American justice is still blinded by blackness. Look at Oscar Grant and what happened on another train platform, this one in Oakland, California.

The set is inventive – chairs turn into cell blocks, a bus, a courtroom. Add a 2 by 4 and one sees a train platform – and the boxcar where all the trouble begins. In a preview interview with Waights Taylor Jr. and one of the actors, JC Montgomery, who portrays Mr. Tambo, I had a very generalized idea of what to expect.

The story is from a perspective outside the Black cultural milieu, similar to Gerswin’s “Porgy and Bess,” which is having its revival on Broadway, with a Susan Lori Parks rewrite. Why not just put “Treemonisha” (1910/1972), an opera composed by famed African-American ragtime composer Scott Joplin, on Broadway? It needs no rewriting! I remember Stern Grove Festival’s staging of the libretto in 2003.

It is the writing in the songs which tell the story, that and the dialogue, like the scene where a younger boy teaches Haywood to read while in the “hole.” Literary is a theme in Kander and Ebb’s play. The irony is the men are not telling this story (smile). Would Haywood appreciate the liberty taken with his story?

I am still trying to figure out whether my life is any richer for seeing the play. One goes to the theater to relax, to be entertained, to be provoked, and of course to think – not to be insulted. Though I wasn’t insulted, my life is certainly richer for knowing in greater detail the story – not the staged version, but through my outside research, namely Taylor’s book and conversations with scholars like Shukuru Sanders, who told me about the Black attorney who was a part of the legal team. He is not mentioned anywhere.

The American theater audience does not look like me in the San Francisco Bay Area, so I am not certain if directors and producers care what Black audiences think. I hope youngsters are getting to see this work, particularly children who are a part of the prison infrastructure – parents locked up, former prisoners themselves or at risk for such fate. These children and adults would bring a different perspective to the discourse.

Who are the Rosa Parkses today? Who are the Haywood Pattersons or Clarence Norrises; they are the first two young men tried and sentenced to electrocution.

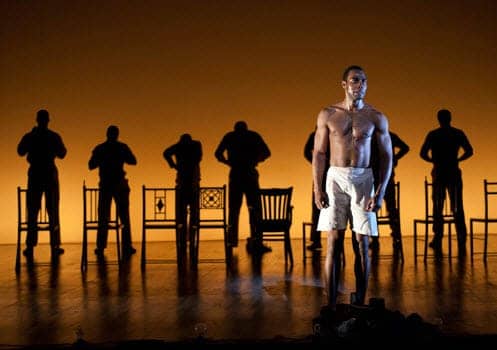

Wright is on stage throughout – perhaps as witness, perhaps representing the community the men came from. Perhaps her presence lets the Boys and their audience know they are not alone. Her mystery is worth the wait, for in the end C. Kelly Wright’s character is “positive womanhood,” in direct contrast to the two white women whose accusations are the reason for the prosecutions.

At one point as Haywood tells his story, a failed escape to see his mother one more time before she dies, the lighting casts the mystery woman’s shadow ethereally over the stage larger than life. The Black woman covers the stage and the sky above and without words brings comfort to the grieving man, Haywood, and by extension, his audience.

Kander and Ebb use the Scottsboro story to usher in the Civil Rights Movement. Rosa Parks was aware of the Boys’ story, as her husband was a part of a defense committee which raised funds for the trials; however, it was the lynching of Emmett Till which really outraged Mrs. Parks, that and her brother’s treatment once he returned from the war, that made her do the work she did as the only woman officer of the Alabama branch of the NAACP.

The men portray all the roles, so men in bonnets are Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. It is the song, “Never Too Late,” where James T. Lane as Ruby Bates confesses to lying; that is one of the highlights of the show. Another song which is really powerful is “Nothin’” sung by Clifton Duncan as Haywood. JC as attorney Samuel Leibowitz, New York attorney in “That’s Not the Way We Do Things,” is great as is his Yankee checkered suit, with Capri length pants, showing off multicolored socks. Listen to the interview with Waights Taylor Jr. and JC Montgomery, at http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks/2012/06/06/wandas-picks-radio-show.

Nile Bullock as Little George and Eugene Williams, 13, the youngest Scottsboro Boy, is impressive in his solos and dancing, especially in the macabre “Electric Chair” scene, which gives me nightmares too. At the end of the tap number, the child is holding a lit light bulb as the guards frighten him by lifting him above the electric chair and threatening to lower him into it. If the intention is to show how this Black child is terrorized, then it works too well.

Another tragically powerful moment in the work is when James T. Lane’s Ozie Powell, 15, takes matters into his own hands and is shot in the head and lives. For a chronology of the Scottsboro Boys’ trials, see http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTrials/scottsboro/SB_chron.html and http://www.sanmarcos.net/ana/Class/Eng2/Scottsboro10th.html.

Visit http://www.act-sf.org/ for information about tickets and the production.

Bay View Arts Editor Wanda Sabir can be reached at wsab1@aol.com. Visit her website at www.wandaspicks.com throughout the month for updates to Wanda’s Picks, her blog, photos and Wanda’s Picks Radio. Her shows are streamed live Wednesdays at 6-7 a.m. and Fridays at 8-10 a.m., can be heard by phone at (347) 237-4610 and are archived on the Afrikan Sistahs’ Media Network.