See the Tavia Percia Theatre Company production at Eastside Arts Alliance, 2277 International Blvd, Oakland, Saturday, Feb. 1, 7 and 9 p.m., and Sunday, Feb. 2, 3 and 5 p.m., tickets at http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/520108

by Malaika Kambon

Fourteen-year-old Emmett Louis Till had no idea of the terrorism practiced in the minds of white folk in 1955 Money, Mississippi, and indeed all over the continental U.S.

Like poet Nikki Giovanni, who traveled from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Knoxville, Tennessee, Emmett Till was not unique in travelling from Northern city to Southern city on the trains for vacation. Emmett, traveling from Chicago, Illinois, to Money, Mississippi, would probably still be alive today if he hadn’t gotten off the train. The children were protected by the Pullman porters and were safe as long as they stayed on the train.

In her prose poem, “Rosa Parks” (in “Quilting the Black Eye Pea,” Harper Collins, 2002), Nikki Giovanni wrote this passage:

“It was the Pullman porters who whispered to the traveling men, both the blues men and the race men, so that they would both know what was goin’ on.

“This is for the Pullman porters, who smiled as if they were happy and laughed like they were tickled when some folk were around. And who silently rejoiced in 1954 when the Supreme Court announced its decision, that separate is inherently unequal.

“This is for the Pullman porters who smiled and welcomed a 14-year-old boy onto their train in 1955. They noticed his slight limp that he tried to disguise with a doo-wop walk. They noticed his stutter and probably understood why his mother wanted him out of Chicago during the summer when school was out. Fourteen-year-old Black boys with limps and stutters are out to try to prove themselves in dangerous ways when mothers aren’t around to look after them.

“So this is for the Pullman porters who looked after that 14-year-old while the train rolled the reverse of the blues highway from Chicago to St. Louis to Memphis to Mississippi.

“This is for the men who kept him safe; and if Emmett Till had been able to stay on that train all summer, he would have maybe grown a bit of a paunch, certainly lost his hair, probably would have worn bifocals and bounced his grandchildren on his knee, telling them about his summer riding the rails. But he had to get off that train and ended up in Money, Mississippi, and was horribly, brutally, inexcusably and unacceptably murdered.

“This is for the Pullman porters who, when the sheriff was trying to get that body secretly buried, got Emmett’s body on the Northbound train. Got his body home to Chicago where his mother said:

“‘I want the world to see what they did to my boy.’

“And this is for all the mothers who cried.”

Emmett Louis Till got off the train in Money, Mississippi, and was brutally and inexcusably lynched and murdered on Aug. 28, 1955.

“Operation Ghetto Storm: 2012 Annual Report on the Extrajudicial Killing of 313 Black People,” a chilling report written by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, proves that the murder of Afrikan people – every 28 hours in the U.S. – still ain’t murder.

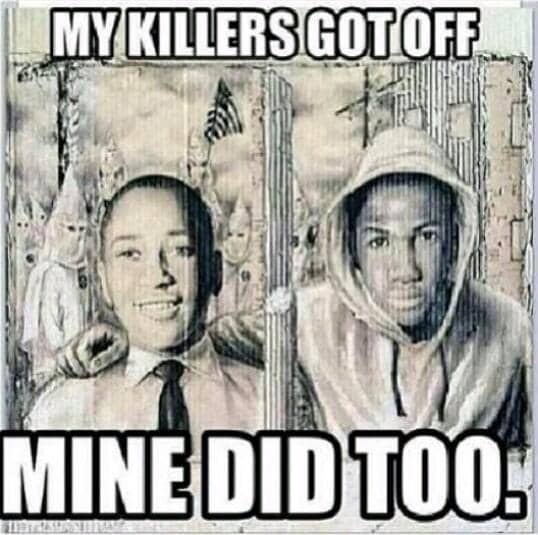

The story of Emmett Louis Till has been told many times in the past 59 years. And despite confessions by his killers, it still wasn’t considered murder, for Emmett Till was a Black male child who didn’t say “Yes sir, no sir” nor hang his head nor grin and shuffle to white people. And he whistled at a white woman.

This was an automatic death sentence – the vigilante, state sanctioned death penalty that is wedded to the lynch laws that are otherwise known as capital punishment white supremacy style. These laws, in effect since the first Afrikan was snatched from Afrika’s arms, state that no Afrikan person – nowhere, any and everywhere – has any rights that a white person is bound to respect.

So, in the 2004 Keith Beauchamp documentary, “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,” in the controversial “pocketbook journalism” confession by killers J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, who were paid $4,000, entitled “The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi,” written by the late William Bradford Huie in 1956 for the old Look magazine; and in Randy Sparkman’s June 21, 2005, article, “The Murder of Emmett Till,” an account of how the story came to be told, in Jurisprudence: The Law, Lawyers, and the Court; even in the re-opening of the case 50 years later, the cold indifference of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and U.S. presidents from Dwight D. Eisenhower to G.W. Bush showed the world that state sanctioned murder of Afrikan people mirrors U.S. politicians and their imperial greed.

No one was ever punished for the extrajudicial killing of Emmett Louis Till. For Emmett Till’s killers were protected.

The kangaroo court jury verdict was not guilty. Laughing, after having been paid $4,000, the killers confessed that they were in fact guilty and proud of doing their part to keep America safe for white supremacy. Double jeopardy laws protected Bryant and Milam from being re-tried after their confessions.

The fact that the original miscarriage of “just-us” was not overturned still hangs like the bodies of Afrikan people from Billie Holiday’s poplar trees, swaying in the wind.

But just as certainly, the struggle of Emmett Till’s mother, Mrs. Mamie-Till Mobley, to bring her son’s murderers to justice is like a timeline that stretches from the far reaches of Afrikan maroons who fought abduction and enslavement, who fought the convict release system after the Civil War – where prisoners worked without pay for the state – and who fought the infamous Dred Scott Decision. The mobilization and awareness of families and communities in the aftermath of the Trayvon Martin, Idriss Stelley, Kenneth Harding, Oscar Grant, Alan Blueford, Troy Anthony Davis, Lovell Mixon, Sean Bell murders – and many more – have grown.

Playwright, actor and director Tavia Percia, 20, with her amazing Tavia Percia Theatre Company, has captured this evolutionary-revolutionary spirit, captured this resistance and is building this nascent movement through the arts.

Like a seed planted from the roots of the Black Arts Movement, this movement is growing among the next generation of artists. And its birth, in this instance, is the presentation of “Emmett Till: An American Hero” by the Tavia Percia Theatre Company on Feb. 1 and 2 – four performances – at the Eastside Arts Alliance in Oakland.

“Emmitt Till” does more than call attention to how Till’s death ignited the U.S. Civil Rights Movement in the ‘50s and ‘60s. It points to the quiet heroism of Mamie Till Mobley in the face of unspeakable horror and unrelieved terrorism.

It points to the strength of Black women, who, in the words of Anna Julia Cooper, are the only women who “can say, when and where (we) enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of (our) womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole … race enters with (us).”

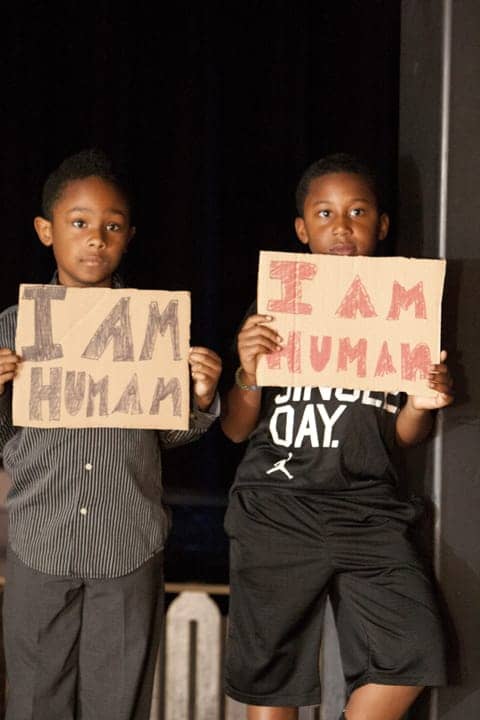

The company’s cast – Lauryn and Joshua Haley, Shavon Moore, Lala Oliver, Branden Thomas, Addanya Reese, Kory Butts, Tali Davis-Watkins, Taji Sivad, Felisha Goodlow, Laila Pina, Erynn Chavis, Ronald Fowler, Antwon Marcel, Charlette Richardson, Charlene Richardson, Royal Hubbard – and director Tavia Percia range in age from 8 to 21, all of them recognizing the significance of Emmett Till’s murder and the similarities to conditions on the streets of Afrikan communities today.

“I went to Oakland School for the Arts,” says Tavia, “so what I did was when I decided to do my first production outside of school, I wanted to use people that I knew – all the talent that was at that school. So that’s what I’ve been doing, you know – all of my friends, people who will do stuff for me because they love me – because I don’t have any money.

“We’re doing this with no budget! Everything is being donated to us by people who want to see our movement become something.”

“Emmitt Till” is very much a message to the grassroots – and a cooperative, grassroots production. Tavia’s friends and Tavia, reciprocating community strengths and resources, always help each other out. When her friends have a show, she helps them; when she does a show, they help her. Like seeds, they are sprouting and growing trees, which in turn bear fruit to feed knowledge and wisdom to the community – and are continuously watered and fed in return.

Tavia, who is also a veteran member of the African American Shakespeare Company, has been doing theatre since she was 12. Keeping in mind that she is now just 20 years old, that means that she has over eight years’ experience in theatre.

And she says of that production and of all of her work, “All my shows are a movement; all my shows talk about how we can rise up as a people.”

That being said, Tavia talks a bit about this production of “Emmett Till: An American Hero,” which is actually the second production with a completely different cast from the first in 2013, in relation to being in the African American Shakespeare Company and the murder of Trayvon Martin.

MK: Tell me a bit about the history of the African American Shakespeare Company. Most people don’t know it exists!

TP: A lot of the plays of the African American Shakespeare Company were written during the time of slavery or before the time of slavery. But Black was still considered negative in Shakespeare’s day and time. And a lot of people who produce Shakespeare’s plays don’t have African-Americans in them because of the time period that they were written in. And a lot of the plays say things regarding color; anybody who was Black was a darkie.

In “Othello,” we get the story of what it was like to be Black in Shakespeare’s time. Even though he was a Moor and he was of stature it was because of a lineage. He was African American, he looked African American but he was light skinned – and it was different when you were light skinned in that day. So basically, during Shakespeare’s time, there weren’t a lot of Black actors and there weren’t a lot of parts for Black people.

MK: Was this during the 16th century?

TP: Yes, this was when men even played parts written for women, when Shakespeare was rumored to have had a Black mistress – and was even rumored to have been a woman himself! But we don’t know.

MK: So it was because of Trayvon Martin that you wrote “Emmett Till: An American Hero”?

TP: Yes. Trayvon died in February 2012. I started writing the Emmett Till story in May of 2012, and I began the production in January of 2013. We did the show on March 9th of 2013.

MK: How was Trayvon Martin a catalyst for the Emmett Till story?

TP: Trayvon Martin was kind of like what happened during Emmett Till’s time. Emmett Till’s story in 1955 was the last straw for everybody. And Trayvon’s story, for me, was like wow, we have all of these people – there was Oscar Grant, James Byrd, all of these people who were murdered at the hands of men who were not African American – and it was OK? It’s OK for that to happen? It’s OK for them to kill off our people?

MK: You mentioned something else that affected you during the time you were writing Emmett Till’s story. What was that?

TP: What really got me was the letter from the KKK in 2010 that thanked us for killing off our own community [references to this letter date back to 1997 and 2005-6]. They’re telling us thank you for making their job much easier. They sent a letter to Black communities. They posted it all over in Tennessee, saying, “Thank you for killing each other. This is our land and you’re saving us some trouble.”

MK: How do you feel that Emmett Till’s death affected the Civil Rights Movement?

TP: Emmett Till’s death ignited the Civil Rights Movement. That’s what this whole story is about! If it had not been for his death, people may not have even been that angry because of the way he died, the things they did to this little boy for allegedly whistling at a white woman. And the things that they did to him were just so gruesome and so unnecessary. Even if he did whistle at this woman, like, so what?

MK: What about Mamie Till? What about her decision to leave the casket open?

TP: Really, the hero in this was Mamie Till. And that’s why she’s the story. She’s the main character in our story. They tried to keep her son’s body from her, and she was like, “No.” We want to make sure that everybody sees this and that as many people hear the story.

We want them to see it, not just hear about it, because we always hear about our people getting killed. But when you see something like this, you realize that this is happening in the North, in the West in California and in the East in New York, as well as in the South, even though not as gruesomely. In the South, they woke up every morning wanting to kill a nigga.

MK: Do you think attitudes have changed much since 1955?

TP: No. I think people try to hide what they feel. Some people pretend that they like Black people. But if I sit next to them on BART, they pull their purse or whatever closer. And I don’t look like I’m going to rob you; I don’t seem like I’m going to rob you. And what about the woman this past October who dressed her 5-year-old son up like a KKK member? She was saying, “This is what I believe.”

MK: You’ve said that your plays are a movement. What do you want the movement to do?

TP: I want to get through to my generation. And when I say my generation, I mean the age group from the womb to about 26. I want my generation to make a better future for the next generation, and that’s why I have so many children in the show because they are learning from this.

For example, Lauren Haley, in the two years she’s been working with us, knows she doesn’t want to be about drugs, alcohol etc. She has dreams, she has expectations, she has things she wants to do in life, and that to me is what I’m fighting for.

MK: There is a picture in the back of Robert and Mabel Williams, who were part of Emmett Till’s generation. They wrote a book called “Negroes with Guns,” which is about Black people who physically fought back against the Klan. This led to the Deacons for Defense, then the Black Panther Party, Dr. King, Malcolm X and the Black Liberation Army.

Do you have a perspective on those occurrences, what you’re doing now and all of the kids in the streets now fighting against police brutality and other issues? How do you tie in what you’re doing and what people are actively involved in now?

TP: My perspective is always an artistic perspective. A lot of people learn and connect best with the arts. And that’s my way of getting to that point. They wrote books. Malcolm X spoke; Tupac sang. This is what we do. We do theatre. We put it in the realm of where people can sit and live through that with us and say, “Wow, I want to make a change.”

And that to me was that significant, even though it was something small. But it is something like that that matters to me. When one person can walk away from a show, from something this small, it is significant.

That’s why I’m so dedicated to this. It takes time, it takes energy, but once it hits, and once people are in the audience and they see what we’re doing, they’re like, “Wow, these kids have worked together to put something together that can potentially change lives!” And that’s what we’re doing. And that’s why we’re doing it.

MK: It’s a lot like when Mamie Till said: “No. I want the casket to be open. I want people to see.”

TP: Yes.

“Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around, turn me around, turn me around, turn me around. Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around. I’m gonna keep on walkin’, keep on talkin’, going to the promised land.”

I encourage everyone to come to see this dynamic and inspirational play by Tavia Percia and the Tavia Percia Theatre Company. The four performances are Saturday, Feb. 1, 7 and 9 p.m., and Sunday, Feb. 2, 3 and 5 p.m., at the Eastside Arts Alliance, 2277 International Blvd, Oakland.

For more information, contact taviapercia@gmail.com, and to purchase tickets, go to http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/520108.

Malaika H Kambon is a freelance photojournalist and the 2011 winner of the Bay Area Black Journalists Association Luci S. Williams Houston Scholarship in Photojournalism. She also won the AAU state and national championship in Tae Kwon Do from 2007-2010. She can be reached at kambonrb@pacbell.net.