The Bay Area Memorial and Celebration of the Lives of Roland and Ronald “Elder” Freeman will be held Sunday, Nov. 23, 12-4 p.m., at the Oakland Masonic Center, 3903 Broadway, Oakland. Brief descriptions of their extraordinary life achievements follow the interview.

by The People’s Minister of Information JR Valrey

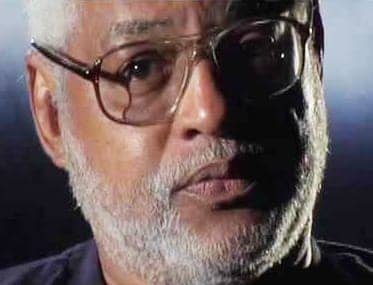

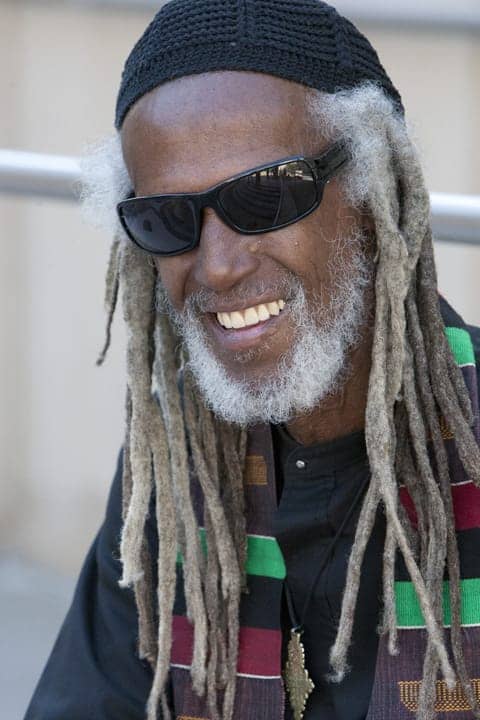

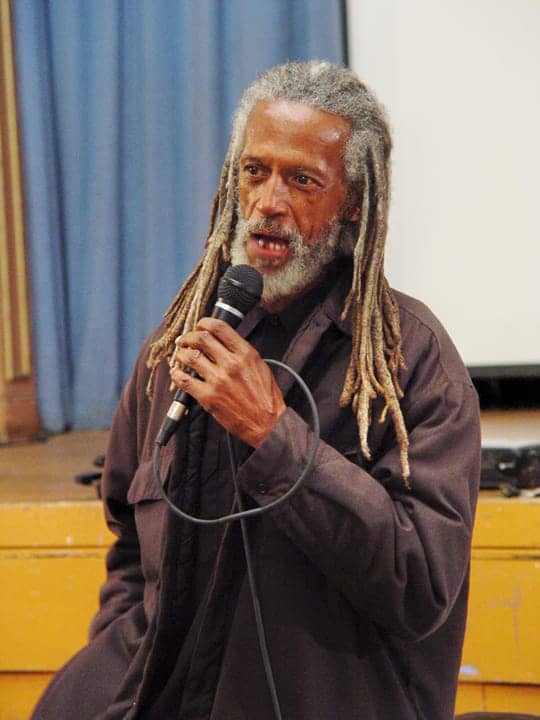

Ronald “Elder” Freeman was a legendary revolutionary pillar in the Bay Area, who made a name for himself first in the streets of Los Angeles with the street organizations, then as the field secretary of the Black Panther Party, under the leadership of Deputy Minister of Defense Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister of Information Jon Huggins, who were both assassinated in a FBI COINTELPRO plot.

He was also a lifelong Garveyite, and he was a priest in the St. John Will I Am Coltrane Church. He was a loving father to his children and a mentor to many over the decades. He transitioned on Oct. 8, 2014.

A week after Elder’s transition, his brother, Roland Freeman, passed away in a New York airport after collecting his brother’s ashes to bring them back to California. Roland was also major pillar in the Los Angeles area, who, a lot like his brother, came up in the streets, then became a notable member of the Black Panther Party.

After the Party, Roland became the local president of the Universal Negro Improvement Association-African Communities League. He also became co-executive producer of the definitive biopic on the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party, “41st and Central,” which is named after the intersection where the BPP office was located, as well as it is the moniker that defined the infamous hours-long shootout, where the Panthers suffered no casualties and the world was introduced to the nation’s first SWAT team. Both Freemans survived this ordeal with the LAPD and the tense climate that followed it.

This is the story of Elder Freeman’s life as told to me in a Block Report interview. He was a mentor and uncle-like community figure at whose feet I sat for half my life, learning from him and his comrades fundamental lessons: true African communalism, how to sincerely love Black people through action, how to truly educate myself, conduct myself in combative situations, think collectively, think strategically, and stand up for myself and community, how to have an international Pan African outlook on the oppression of Black people, how to be forever a student and problem solver, as well as defender of the people. These were just a few of the jewels that he taught me directly.

Here is the story of two legends who gave everything to their people for decades and continued to their last breaths. Salute to two of the finest examples of principled Black men that I have ever had the honor to meet and become close to. Here is Elder Freeman in his own words. All Power to the People!

M.O.I. JR: You are listening to another edition of the Block Report with the Minister of Information JR. Today our honored guest is the legendary Black Panther from Los Angeles, Ronald Freeman. Ronald Freeman, how are you?

Elder Freeman: OK. How you doing, JR?

M.O.I. JR: I’m good. I wanted to talk to you about your history in the Black Panther Party. Can you tell the people a little bit about what was happening in Los Angeles before the Black Panther Party started and what created the environment for the Black Panther Party to flourish in Los Angeles?

Elder Freeman: One of the things I’d have to go back to was in ‘65 before the Party started, even up here, is that the people in Los Angeles, due to exploitations where prices in the stores was higher and the police was basically being used as an occupying army as far as in relation to harassing young people like they do today – that hasn’t changed – and what gave rise to it is the people’s consciousness in LA as far as wanting to commit themselves to make a better community, looked at it in different ways.

Some of us looked at it as to where a community had to be protected from outside forces, and there was a better way for our community to be policed and a better way for the justice system to operate as far as in dealing with Blacks and the judicial system being our prosecutor. We wanted to see the killing in our community stop, and the Black Panther Party was a vehicle used to reach that end, because it had a 10-point program and was addressing the needs of the community in more than one aspect.

M.O.I. JR: What did the Watts Rebellion have to do with it?

Elder Freeman: A lot. You know, it’s like the conditions of the community, because it was like a continuous process – like a boil if you have a sore. It has to come to a head and it’s going to bust. So the harassment of Black people in the Black community by the Los Angeles city police and county – and it wasn’t just the police, it was also the sheriff. Los Angeles has a very racist and Gestapo sheriff’s department as well as the city police department, and they both were harassing, intimidating and murdering our people in the Black community.

Then it boiled to a point to where people had to respond to it. Enough is enough. And that led to even more Black people getting killed in a rebellion that were being murdered by the police and the army that came in and just gunned people down. As a result of that, people wanted to see things change within the Black community.

M.O.I. JR: Who was Bunchy Carter and how was the Los Angeles Black Panther Party founded?

Elder Freeman: Bunchy Carter was – well, the first thing I have to say is he was a very dynamic human being and he had a love for his people that was unbounded because he wanted to see the situation in the community really change. He was, as a young man, as well as myself – we were in different parts of the city – we were part of social groups. Some people call them gangs.

I ain’t got nothing against the word “gang.” I think we all need to gang up. You know, the system is ganged up against us and we need to gang up if we want to have any kind of life within our community. So I believe in us coming together socially and dealing with things.

But this was in the streets and it was done with young Black men organizing themselves into groups, and Bunchy was on the East Side and I lived on the West Side. But he was the one that organized a group called the Slauson Renegades; he was a Slauson.

And his organizing abilities exceeded anybody else. Because the group that he had became the major and the only – really – group in Los Angeles at one period. It was the only time in the history of Los Angeles where all of us were from one group. There wasn’t no Crips or no Bloods. There wasn’t none of that.

It was just Slausons. And so as far as us coming together as a group, we all had banded together as one. I mean Bunchy had banded the younger people as one. They were a group just a little bit younger than me and they were united in one group, and Bunchy was the leader. So nobody ever did that. Nobody else did anything like that.

M.O.I. JR: What years are we talking?

Elder Freeman: ‘64, ‘63. That’s when they were starting to rise up at lot. I guess you could say ‘63. In ‘64 our people wasn’t really engaging in that. A lot of us had got older and had children and families, so we wasn’t really in the streets as much. It was in the years before ’65.

So when ‘65 came and that thing happened, it was like all of the different groups kind of banded together and it wasn’t whether you was from Boot Hill or you was from Vineyard or you was from the Gladiators or the Businessmen or the Farmers or the Slausons.

It was all about our community having some rights. So young people was looking at things in a different light. They wasn’t looking at things as far as just for themselves. If the community was doing good, everybody else was doing good.

So for a period there, the community was united and moving in one direction and that was that our situation had to change and it had to change now. So that was a time of change. I changed. A lot of people changed how we looked at things.

M.O.I. JR: So what made you guys open the doors? Where was the first office and what led to the actions that opened the doors, and when did you and your brother come in?

Elder Freeman: Well, me and my brother, we got involved at the end of ‘67 after Huey got arrested. And Bunchy Carter was in touch with the Black Panther Party previous to that and they were talking about forming a chapter just prior to opening up that Black Panther Party.

Well, see it was just calling different people, saying, “Hey, we gon’ start a Black Panther Party in Los Angeles. Come to this meeting.” And then my brother went and we met Bunchy and we made a commitment at that time that we was going to struggle for the liberation of our people. You can call it the Mau Mau oath. So we committed ourselves to a struggle for our people. From now on, they could kill us or whatever happens.

So from that point on I got involved. I was at our first offices. We just had buttons and things and they were fixing to start the Free Huey Campaign and so in the next year in January or February – yeah, February – we officially opened up a Black Panther Party in Los Angeles. And our office at that time was at the Black Congress. Then we moved from the Black Congress.

We got our own office a couple of months later in ‘68, in the spring of ’68, at 41st and Central. Then later on, maybe about two years later, they had the shoot-out in Los Angeles – and that was our headquarters on 41st and Central, which I’ll probably talk about later – the shoot-out with the Los Angeles police for over four hours, where they tried to raid and kill Black Panthers. I’m getting ahead of myself.

So our first office was on 41st and Central, but the plan that Bunchy had in place for us was that because of the size of Los Angeles we were going to have to have more than one office. And by Bunchy being in charge of Southern California, which extended from Bakersfield on down to San Diego to the Mexican border, offices had to also be established in other regions where there were Black communities.

And because our plight is the same and the conditions that we all were experiencing were the same – the capitalism, the racism, the exploitation – it wasn’t just confined to Los Angeles. It’s an international phenomenon. It’s not just America.

So all over America – in New York, Detroit, in the South – everywhere we were all being exploited and our conditions needed to change. And in order for them to change, the whole system had to be rearranged. And so we participated in the politics to change that.

So we opened up a few more offices in South Central Los Angeles, also in San Diego, Santa Ana. We had people in Pomona, Riverside, Bakersfield, Santa Barbara, Venice, Long Beach, Compton. So we had offices in several cities.

M.O.I. JR: Where was central headquarters for Southern California?

Elder Freeman: Central headquarters was still at 41st and Central in South Central Los Angeles.

M.O.I. JR: What were the Black Panthers doing at UCLA? Eventually, some of the political contradictions and issues that you guys were having at UCLA led to the assassination of Bunchy Carter and Jon Huggins. What were the Los Angeles Panthers doing at UCLA and how did it culminate into those two being assassinated?

Elder Freeman: They had a Black Studies program going on at UCLA, a program that entered the Black community through Black students from the Black Students Union – or I should say through SNCC – where they were coming into the community and working with the community on the programs that they had done in the South.

They came in Los Angeles and did a similar thing by Black college students entering into the community and working with the community. So from that, there were some programs that were established for Blacks to go to college at no cost, so some Panthers entered that program, an experimental kind of program they were having at UCLA because there they were going to set up the Black Studies Program that was instituted at a lot of the colleges and universities that they have going on today.

Those programs were outlined to guidelines for the Black Studies Program which was going to be implemented at UCLA. And so the Panther Party wanted to have an influence in that as far as its relationship to the Black community to insure that part of the program would have in it Black students who would have buildings and institutions within the Black community where it was part of their curriculum to serve the Black community as far as tutoring students, helping students as far as establishing schools and different kinds of training programs within the community coming from the college.

If they would have did that back in the ‘60s or ‘70s, that program would have been going on for over 40 years. We would have been better educated and better trained, and people would have been able to provide for themselves if that program would have been instituted within the Black Studies Program.

It wasn’t – and two Panthers lost their lives to implement that, where two Black organizations by the FBI were pitted against each other and made to come to the point where they were killing each other.

That’s basically the truth of what it was. You know the system didn’t really want to see this kind of program implemented in the community. Even the FBI themselves claimed they took part in planning the assassination of Bunchy. It just happened at one place instead of another. They wanted him dead.

Even the FBI themselves claimed they took part in planning the assassination of Bunchy.

M.O.I. JR: Well, can you also talk about the relationship that United Slaves had to it about you being shot by United Slaves and what happened in that incident?

Elder Freeman: I guess I can make it a little bit more clear that the system, the FBI and the LA Police Criminal Conspiracy Sections and other agencies, they come to find out through their wiretaps and their informants and stuff that there was a contradiction that existed between Black organizations, and they took advantage of that. They pitted one organization against the other and used, to be honest, both organizations against each other and misdirected the whole thing.

That never should have occurred among Black people, but that’s due to our ignorance. Those kind of things happen where we end up killing each other, and we’re still doing it to this day. This is something that really needs to be reversed because a lot of times – I don’t know, that’s where people say we can be our worst enemy and us murdering each other is a true factor of that.

But it clearly shows that we have a problem within the Black community with each other, with ourselves getting together and organizing ourselves in a manner that’s going to bring about some positive social change and good to our community. We have a problem with doing that. That’s something we need to stop. We have to stop that, but we’re still doing it.

So I’m talking about even down to the street people associations, even down to us becoming soldiers in the United States Army. You know, the whole thing about us participating in the murder and killing of other human beings and the manner that we do it is something that we need to stop doing.

M.O.I. JR: Can you talk a little about what did Bunchy and Jon being assassinated – what did that mean to the Los Angeles Black Party and the Black Panther Party as a national organization? Because when I still travel to Los Angeles and I look into some of the veterans’ eyes of the Black Panther Party, when you say Bunchy Carter, their eyes light up. What died? What was assassinated with Bunchy Carter and Jon Huggins?

Elder Freeman: You see, that’s the whole thing. When I go to talking about it turning into one group – the Slausons was the only group that was in Los Angeles – is that his ability to organize, his ability to get people to do things is that he took that ability, instead of using it – we could say like George Jackson – instead of using it as a predator mentality, he turned it around into a revolutionary mentality to work for change.

He took that ability that he had and used it for his people. He was the best organizer I’ve ever seen. He had the ability to put things together, put the structure together and make it work and he was a genius in that. He was definitely a threat. He thought about the Black community in total social respect – I mean elements.

It’s like the whole thing about our schooling, we had to have jobs, we had to have medical care and we had to have the police to stop attacking us and abusing us. We needed protection, and we also needed to activate our constitutional rights to bear arms and to protect ourselves and form militias to protect our community. In other words, we needed a community policed by the community, not by outside forces.

We needed a community policed by the community, not by outside forces.

So the whole idea was being able to want to form self-defense groups to protect the Black community was high on his list. And this posed a threat to the system. Because of his charm and his ability and his magnetism to organize, he was someone that had to be removed. And Jon – he was intellectually so talented and sharp as far as being able to decipher information and expound on it was great.

So it was two elements that was removed from the Los Angeles chapter and whole national party by the removal of Bunchy and Jon. Because a lot of things that happened with the Party, we were kind of used as a testing ground. You know, the breakfast program when it came out of the Bay Area, it came to Los Angeles. And other programs – the buses program and different programs – going into the community to get surveys and looking after the elderly.

At that time they didn’t have direct deposit. Elderly people had to be taken to the grocery store, taken to the bank because there were predators out there. So these were kinds of services we were providing to the community back in the ‘60s.

We started other things besides just the breakfast program to assist people to have nutritious food. We gave away bags of groceries and things like that. So a lot of us Panthers ended up in jail. But it was something that we knew we had to deal with anyway because of the injustices that were occurring.

Huey was on trial, the whole Free Huey Campaign was an educational program on the injustices that we all know were being committed then and are still being committed today within the system because of how we enter into these courtrooms and be prosecuted.

M.O.I. JR: Can you bring us to the lead-up to the shootout on 41st and Central. What happened right prior to that? What was the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles engaged in at that time and take us to that moment.

Elder Freeman: Well, what I know we were doing for sure was we had our breakfast program going on and selling of the newspaper. They were selling thousands of papers in Los Angeles and they had several breakfast programs and plus they were starting a bus program to prisons, a free clinic, and they were doing sickle cell anemia testing back in ‘69 before anybody else was doing it.

Secondly, a lot of things that we were doing were contradictory to the system because some of the work we were doing in that area was showing a contradiction between the children going to school hungry as opposed to children being able to have a full meal, showing a contradiction that the government was not addressing the needs of the people.

And by that, with the sickle cell anemia testing, it was showing that that sector of Black people were affected in large numbers and other races of people. We started testing people for that, and that was something that the government should have been doing. Now the government has taken over that program and has taken over the breakfast program. Now we have this Medi-Cal stuff where we were talking about people’s well-being.

So these things were going on, which may seem small in themselves, but it made the Los Angeles police intensify their efforts against the Black Panther Party to see that these programs were not successful. Therefore, by raiding offices, planting informants in the offices, giving us illegal weapons and illegal explosives and stuff and then turning around and raiding our office, saying we got illegal stuff – and that’s where we got it from was from the government.

All this is documented now, but they did a lot of things. They did the whole thing with the US Organization – they pitted us against each other. They drew the cartoons showing Karenga’s men being attacked by Panthers and then showing the US Organization attacking Panthers. It was all orchestrated, illustrated by the FBI.

They drew the cartoons and sent them to different people and letters and different things to pit people against each other, which caused a lot of people to lose their lives in Los Angeles – I wouldn’t say unnecessarily, but their lives were lost for something that was sidetracking from what they were doing and what they committed themselves to.

People got caught up in something that they hadn’t anticipated at all: Blacks fighting each other. But we know from our history, we were fighting each other, but we didn’t expect it to occur back in the ‘60s. So it was very tense in Los Angeles with the Los Angeles police.

People got caught up in something that they hadn’t anticipated at all: Blacks fighting each other.

So they were after us. J. Edgar Hoover had put out that he wanted us to be destroyed, he wanted us to be neutralized, and that’s what they did through their informants and murders.

M.O.I. JR: Take us back to 41st and Central. So what day was that? That was in January? I know it wasn’t too long after the assassination of Fred Hampton.

Elder Freeman: It was a few days after Fred was murdered.

M.O.I. JR: So it was like on the 8th or 9th of December?

Elder Freeman: Yeah, it was like the 8th. Well, Fred got murdered on the on the 6th.

M.O.I. JR: So what was going on that day?

Elder Freeman: That day, from my understanding, at the time hadn’t nothing started because the police raided and ambushed them at 4 o’clock in the morning. People were sleeping.

And so what occurred the next day was people were doing the different breakfast programs where they were serving breakfast. And after the breakfast program, people would usually get their newspapers and go out and sell their papers and spread the word about the Black Panther Party – what we were about, what we believed and what we wanted – and doing the daily activities: collecting donations for the breakfast program, seeing if they had started the clinic and seeing if the people were operating the clinic and just the daily operations of the Panther Party involved with the programs that we had.

The office was opened up. We had to make sure our office was opened up every day, that it wouldn’t be closed and it would be open to the people seven days a week.

M.O.I. JR: So when we talk about 41st …

Elder Freeman: At 41st we were sleeping when the police raided and ambushed and tried to murder them at 4 o’clock in the morning. That was their intent. They came in to murder everybody who was in there.

That didn’t happen because we had fortified our offices. We had an executive mandate from the Central Committee of the Party there: We had every right to defend our offices and property and that if anyone came in to attack us, we would defend ourselves – and that’s what happened.

If they wanted, they could have come around when the office was open. I mean this was no urgency that they had to come in at 4 o’clock in the morning, but that’s what they did and they met armed resistance. Four or five of the police got shot and four or five Panthers were wounded and nobody got killed.

And they tried them and nobody got convicted for conspiracy; a couple of gun charges people were convicted for or lesser offenses. That was it. Most of the people got found not guilty. They had the right to defend themselves.

M.O.I. JR: Why was it important in Panther history? 41st and Central – there’s a documentary about it and the Panthers from coast to coast talk about 41st and Central. What was important about that particular battle?

Elder Freeman: Well, the whole thing was they were just coming in and exercising whatever kind of force that they had, and it was met with equal force. It wasn’t a situation where Blacks just surrendered and gave up.

It was something that our people could look at with some kind of pride as far as they tried to murder some people and people resisted the murder. Like the bombing of MOVE; they murdered those people. And that was something that we fought against and this was something that people had a right to do, to defend themselves.

So what I can say as far as in relationship to other Panthers, they looked upon it not only with respect and dignity but it was something that people were proud of. People felt better about themselves for what they were doing and they felt like – I don’t want to say a sense of accomplishment, because people’s lives were on the line and they saved their lives – but people felt like defending themselves like that, so they didn’t lose their lives. And this is something that we should be proud of that we defended ourselves.

So everybody felt good about what happened in LA in relation to that because nobody got killed – didn’t no Panthers get killed – and trying to set an example for people trying to protect themselves when they’re met with force. We had a right to defend ourselves and everybody felt good about that.

It encouraged people to feel good about themselves for getting involved with things. The people in the community felt that these people are doing something for the community. And more people were getting involved because of the actions of the Black Panther Party as far as trying to resolve the contradictions between the state and the people.

M.O.I. JR: One of the biggest criticisms that I hear of the Black Panther Party within the Black community is that they say the Black Panther Party was a nationalist organization and gave its nationalism up for internationalism. Can you speak on what is your analysis of that?

Elder Freeman: Well, we look at the struggle inside of the United States. There’s a national issue there in relationship to Black people in America: Due to the exploitation and oppression and the racism inside the United States in regards to slavery, we have issues that we have to address with the United States government. It’s not the same as the slaves that came to Brazil or the slaves that came to Cuba. The ones in North America had issues.

So that’s when it became like a national organization in relationship to addressing the issues inside the United States. Internationally and being realistic in our struggle, if we were to bring about any change in America, it had to be connected with the international community. And that’s what Malcolm X and other people were emphasizing, that our issues need to be brought to international attention.

Or you could say like, for example, the Marcus Garvey movement was an international movement, but in a sense you could say it was addressing a national issue because it was addressing the question of all Black people in the world. That’s international, but you also had a problem inside the United States with the racism and the exploitation that the United States had to address.

So we became from nationalists to internationalists, because when you look at the situation, it’s an international problem that we have. So it’s not just a United States problem; it’s a world problem. And to solve the problems in the United States, we have to address this to the whole world.

We can say how the U.N. doesn’t really work for the benefit of all the people of the world, but it’s a process that’s been set into motion. Like now, in Africa, you’ve got the African Unity where all of the different African states are trying to work together. Those are the kinds of things that need to be going on.

So the Panthers – we had a national view and an international view as far as the world and as far as the United States. So there’s the national question and the international question, and we preferred to participate in both as far as what you could do in the area where you were living and also how that area connected to other parts of the world. So we became international.

M.O.I. JR: Another thing happened in California that was real big in 1970 – and it didn’t happen in Los Angeles, but it happened in the Bay Area – and that was the assassination of Jonathan Jackson. Can you tell us how did that affect Los Angeles? What was Los Angeles talking about, what was Los Angeles thinking about when Jonathan Jackson was assassinated?

Elder Freeman: Two things occurred. You had people feeling double emotions. They felt good about him trying to make a statement about how the judicial system is corrupt and how it doesn’t benefit the Black community in any way. We felt proud of this young man and what he did because they understand what the justice system is all about and how corrupt it is and that whole process.

And other people were very sad about the whole thing because he was murdered, people got murdered, he lost his life – and that was the sad part about the whole thing. But he made a statement as a young man that the injustices going on inside the United States needed to come to a halt, and if it called for measures such as he took to make a statement about how corrupt the system is and he lost his life in the process of that … our people looked at it in Los Angeles with mixed emotions.

M.O.I. JR: What about when George was assassinated a year later?

Elder Freeman: I was in jail myself, but I can say this. When George Jackson was killed, the response to that was you ended up in the next month with Attica, the prison in New York, protesting or rebelling against the conditions they were suffering up under. George Jackson and the whole prison movement are connected.

George Jackson and the whole prison movement are connected.

And a lot of things happened after George was killed. And the response to his murder – a lot of different people in the world and in this country responded in different ways, because he was definitely murdered inside prison. So were the young men in Attica; they were just murdered.

So murder inside prison is not only – well, people talk about it occurs between prisoners, but it’s also the guards killing inmates. You would think it’s unthinkable, but it occurs. Guards have been killing prisoners for over 100 years.

M.O.I. JR: So what did George Jackson mean to the Black Panther Party? I know that a lot of you all were reading his book, and he had a phenomenal movement behind prison walls. So for those who know nothing about George Jackson, what did he mean to the Black Panther Party?

Elder Freeman: Well, right off the top of my head, I would say he meant resistance. He meant that you don’t ever give up, that even though you’re put in terrible conditions, you have every right to oppose the inhuman treatment and inhuman conduct as being presented by anyone.

You have a right to oppose that, and that’s what was occurring inside the prisons in the United States. They’re brutal. The most dangerous place you can be in the United States is in prison – and it’s supposed to be a place for rehabilitation and it’s supposed to help people to be able to come back into society and function in society. That’s not even in their program. They have no guidelines about that.

The most dangerous place you can be in the United States is in prison – and it’s supposed to be a place for rehabilitation and it’s supposed to help people to be able to come back into society and function in society. That’s not even in their program.

Their thing is just to house you and keep you until they let you go – or they bury you. So George’s whole thing was that although you may be in prison, you still had human rights and that you needed to be treated as a human being. And he was working towards that inside the prison and other inmates – people – inside the prisons joined him because of the conditions.

They felt that they needed to be changed, and they identified with that idea – and it became a whole movement inside the prisons for prisoners to be changed and make it where people could be treated as human beings and be able to have the necessary things so that they can learn inside prison, so when they leave and come back out, they could be an asset to the community instead of a liability.

George Jackson would say, change the predator mentality to a revolutionary mentality. In other words, change your thinking from beating up people, robbing people, burglarizing people to helping people, feeding people, clothing people, helping people get jobs.

Doing things for people instead of preying on the people is what George Jackson was teaching. And why he was so respected in the Black Panther Party was because of his commitment to social change. Even though he had been confined to the dungeons and the pit-holes of this society, he was a strong enough man to want to still have his mental faculties that he could see that this society needed to be changed and people in prison were identifying with him – and they killed him.

Doing things for people instead of preying on the people is what George Jackson was teaching – and they killed him.

I could say right quick about George – other people might know other things or could elaborate on his documents, his philosophy and his teachings – but the main thing: He was an inspiration for people who could see no way out or had no hope to where they’ll never give up. They’ll never give up.

M.O.I. JR: So what was the relationship to the prison movement? What relationship did the Black Panther Party have to the prison movement? I mean, was it a direct relationship or was it an indirect relationship? Was George, being a field marshal in the Black Panther Party, was that symbolic or was there really a Black Panther Party that was operating with George Jackson?

Elder Freeman: Well, that part I don’t know too much about. It would seem from our perspective that it was more symbolic although his relationship inside the prisons – his position and people having respect and honor for him – was heightened and I think it was heightened even among the Panthers on the streets.

The connection of drawing the prison movement and the Panther Party more closely together – that was coming into being. But it never really got started because they killed it before it could really happen. They killed George, they killed other people in the prisons, they transferred people to other states and prisons, so they just broke up the leadership.

So today, in 2014, if you get caught in a California prison with a George Jackson book or a George Jackson statement or a quote from George Jackson, you’re going to the hole. You’re going to be persecuted for identifying with him just like how people were persecuted for identifying with Jesus Christ.

So today, in 2014, if you get caught in a California prison with a George Jackson book or a George Jackson statement or a quote from George Jackson, you’re going to the hole. You’re going to be persecuted for identifying with him just like how people were persecuted for identifying with Jesus Christ.

I mean, they will put you in the hole for 40 years – as people have been in the hole in California for 30 or 40 years just because of the system saying they knew George Jackson. He was a force to be dealt with because he was for the people.

M.O.I. JR: Can you talk a little about the feud that happened between the East Coast and the West Coast that was personified between Huey and Eldridge? Can you talk about what was your position, what was Los Angeles’ position and what happened?

Elder Freeman: I have to put it like this. What happened is that the media – there was no East Coast and West Coast, but we can say to a degree that there was Huey’s part of the party. Eldridge, what he did was he came to the defense of the people that had been overlooked and neglected that was in the party, and Eldridge just was pointing out the plight of these people and that their positions needed to be addressed.

And Huey said those people needed to be put out of his party. And all of a sudden, although Huey started the party and it was his party and all that, I didn’t understand that. I didn’t join his party; I joined the people’s party. And all of a sudden it became the personal property of Huey. Our opinions and what we thought about things didn’t matter.

So when Eldridge came to the defense of the people being wronged by the Party, then the news media made it Huey’s side and Eldridge’s side. And Eldridge wasn’t even in the United States; he was in Algiers. But the problems that people were having were in Los Angeles and New York and Chicago.

A lot of it was with people’s court cases and things like that – like the New York 21, their court cases and stuff. They were complaining about the lack of dealing with their defense and how things were being handled, and they tried to address it to the Party. And the Party didn’t respond.

The Party said they went outside of the jurisdiction of the Party to criticize the Central Community, so therefore they were kicked out the Party. And Eldridge came to their defense or they said some of the Panthers in Los Angeles were kicked out for their behavior – and that included Geronimo and stuff like that and these were people that were really dedicated to the struggle.

So Eldridge came to their defense. And so what happened basically in the Party, there was a split between, I would say, the people that had more of a military leaning – all those people and all that element of the Party – were kicked out, left. That part of the Party broke away that had more of a military character.

So I don’t want to say that one part was more political than the other. It was just that the political apparatus that was connected with the military, it all broke up. That was, it seems like, by plan and from everything that I know of, it was another FBI COINTEL thing to cause division and cause us to be fighting and bickering among ourselves, which went on for just a minute and caused us not to focus on the struggle.

And the Party was destroyed and the people in the underground and all of that – it was destroyed. So the movement that we had in the ‘60s that we had developed to that point was set back several years.

So now what we’re engaging in … I really don’t know. I don’t know what we have to do now to raise people’s consciousness to want to change their conditions. Because the system is doing everything it can to create the conditions for change because of the exploitation and the racism that they show inside the United States. Like a bump or sore that has to come to a head – it’s going to bust.

And what’s going on in the United States, it’s going to bust. It ain’t gonna keep going on. That’s for sure.

What’s going on in the United States, it’s going to bust. It ain’t gonna keep going on. That’s for sure.

M.O.I. JR: So in terms of talking about your personal history and your family’s history, how does the Garvey movement sit with the Black Panther Party movement? Did the two collide? Did you become a Garveyite before and then dropped it later or were you always a Garveyite, you and your family? Like, how did it work and do the two philosophies collide?

Elder Freeman: Well, if we’re dealing with ideologies, they do. With my family, my grandfather was in the Garvey movement and even got to the part of the history where when Garvey got sent out of the country, (other leadership) took over a little bit with his philosophy in the ‘30s. So my grandfather was a Garveyite and then also a (follower of the successors).

The Panther Party – it had similarities in relationship to addressing the community and the things that we should be doing for ourselves because that’s what the Panther Party was showing us, that the government has a responsibility to make sure that our children are not going hungry. But we also have a responsibility to make sure our children are not going hungry, so we should do everything in our power to see that our children are fed. That’s a Garvey kind of principle.

We should be concerned about employing ourselves. We should talk about the government, about the lack of employment that we have. But at the same time, there’s enough resources that come through the Black community, if we took those resources and turned them around and directed them towards other Black businesses and spend them with each other and build up other institutions – schools and businesses in our community – that’s kind of a Garvey principle.

What we need to do for ourselves is create businesses for ourselves and do for ourselves. So those kind of things, definitely the Garvey movement has – I mean even in the thinking and the ideology of the Black Panther Party – it has an effect on their thinking because it preceded the Panther Party; it preceded the Nation of Islam.

It was something that Black folks back in the ‘20s were identifying with. Because you have to realize that we had just come that far from out of slavery. You know, there were still a lot of people who were alive back at that time who were slaves.

So the whole thing about us separating ourselves and doing things for ourselves was something that was kind of embedded in the community, but it had no structure until the Garvey movement came and millions of Blacks expressed their desire that they wanted to do for themselves and they don’t need the United States government to do for them.

But at the same time the government does have a responsibility and an obligation to the people that it governs to see that they have an adequate life. And that’s where the Panther Party addressed that as far as what the government should be doing for the people.

In return, we the people, we could do for ourselves. And that’s part of what the Panthers were expressing because they were instilling pride in us and therefore we would be participating in our community, which is what we need.

The Panthers were instilling pride in us and therefore we would be participating in our community, which is what we need.

We need adults, we need everybody to be working together instead of sometimes lending it over to other people like the government to take care of our education, to take care of our health needs and things. We also have a responsibility to ourselves to see that our basic needs are met.

So you could say the Garvey movement influenced the Panther Party to a degree, but we were young people and we wanted to see social change. And we saw that the government had a responsibility to the people, and we were pulling that contradiction out.

If we were going to have a government, we needed a government that was going to reflect our ideas, our needs and our wants. So therefore the United States government, because of its racism and its exploitation, needs to be changed in relationship to Black people. That’s how we were thinking at that time. So we were nationalists then. We were talking about the United States government.

If we were going to have a government, we needed a government that was going to reflect our ideas, our needs and our wants. So therefore the United States government, because of its racism and its exploitation, needs to be changed in relationship to Black people.

I should talk more about how the Garvey movement influenced my life because where I grew up in Detroit, it was a Garvey community. They had those communities back then – I mean, you can’t even imagine. Your next door neighbor and your neighbor two doors over, across the alley and down the street, around the corner, where’s there’s seven or eight people – and they all belong to the same organization. You know, people on the next block – all these people belonged to the same organization.

We had a community that had a level of consciousness, so I would always hear when I was a little child about doing for yourself. When I was a little kid in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, Black businesses were prominent then and they had all these little stores that was in the community, in people’s basements, in their living rooms, and they would have refrigerators and everything to keep the stuff cold. I mean they had little stores all over the community even before the big supermarkets.

So there was a sense of community. People would get sick – all the neighbors would help each other. Everybody knew each other, so there was a sense of community, which we don’t have now. So it was people that you could be going somewhere and they’d be telling you, “Boy, when you grow up, you start your own business.”

People would be telling you, “Boy, when you grow up, you start your own business.”

I mean it was things that motivated you to want to have your own business. You could see people that were operating – they had barber shops, beauty shops, corner stores and other business. They had things like – we don’t think about it now – but selling oil and coal and firewood and stuff for the wintertime. That’s a business.

So you would see all these different businesses, and these were Black people that were running all these businesses. And I don’t know if it was a bad thing that it ever went away, but segregation – we had all of these things in our community because we were separate. We had to have all these entrepreneurs in our community because we couldn’t go into the White community even if we wanted to. I don’t know if we wanted to.

But there was this whole integration movement going on where people were talking about integrating and stuff, so I grew up in that. I grew up in an environment where they were telling you to be proud of yourself and to accomplish something in your life. We don’t have those kinds of communities no more.

I grew up in an environment where they were telling you to be proud of yourself and to accomplish something in your life.

M.O.I. JR: You were just listening to the voice of Elder Freeman, legendary freedom fighter, former member of the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party.

The People’s Minister of Information JR Valrey is associate editor of the Bay View, author of “Block Reportin’” and “Unfinished Business: Block Reportin’ 2” and filmmaker of “Operation Small Axe” and “Block Reportin’ 101,” available, along with many more interviews, at www.blockreportradio.com. He can be reached at blockreportradio@gmail.com.

The extraordinary lives of Roland and Ronald ‘Elder’ Freeman

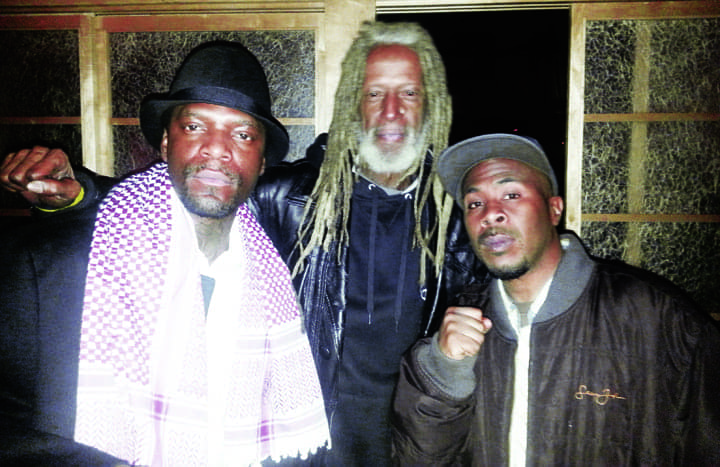

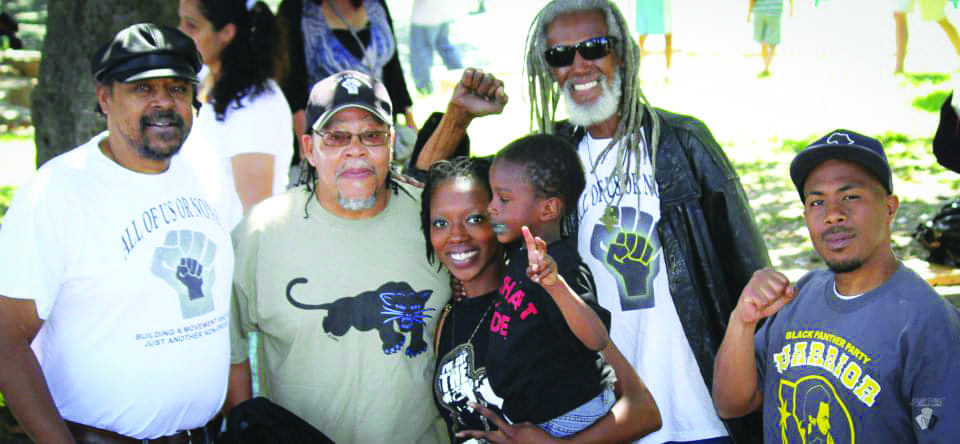

by Manuel LaFontaine, All of Us or None

The Freeman Brothers were deeply involved in our communities, fighting tirelessly for social justice, while serving the people. Please join us to celebrate the lives of these two community servants.

Ronald ‘Elder’ Freeman

Ronald Gene “Elder” Freeman was born on Nov. 13, 1944, in Detroit, Michigan, to Glathie and Columbus Freeman. The family relocated to Los Angeles in 1961. After being encouraged to attend a Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) meeting by his brother Roland, he whole-heartedly embraced the movement and from that point on dedicated his life to fight for the rights of oppressed people.

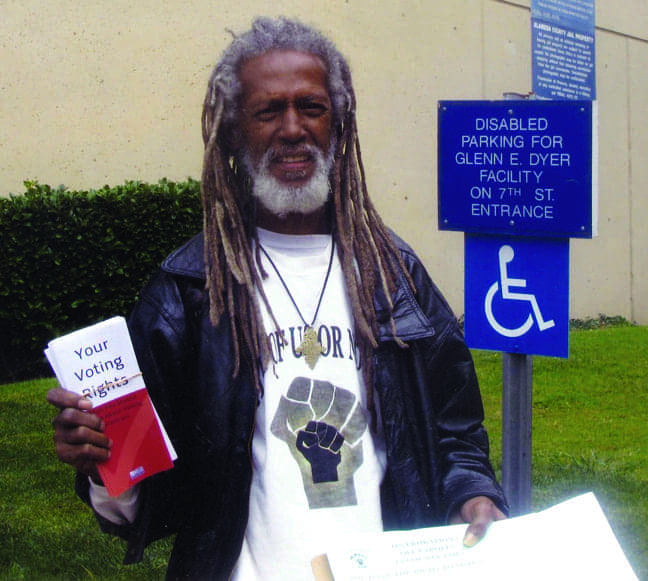

Elder was a field secretary for the BPP. He relocated to the Bay Area, where he was ordained arch-priest of the Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane African Orthodox Church Jurisdiction of the West. He was also a co-founding member of All of Us or None, an organization dedicated to fighting for the civil and human rights of prisoners and formerly-imprisoned people.

He spearheaded many campaigns, was always engaged with his community and continued his humanitarian work until he was no longer physically capable. Elder leaves to mourn Carmelita Taylor, mother of his two youngest children, Menelik and Tiye (who preceded him in death), stepson Khalil, his oldest daughters Rhonda and Niteese, seven grandchildren, and a host of family, comrades and friends.

Roland Freeman

Roland Hugh Freeman was born on Nov. 11, 1945, in Detroit, Michigan. During the time of the heightened racial tension of the 1960s, Ronald and Roland got involved in the struggle against racism, injustice and police brutality against Black people in Los Angeles and all over the U.S. He and Ronald joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1968, under the leadership of Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, who was the deputy minister of the Southern California Chapter of the BPP.

Roland, a section leader in the BPP who was known as “The Great Organizer,” was one of the members involved in the attack against the Party by the LA SWAT team on Dec. 8, 1969, at the offices on 41st and Central in LA. He was eventually acquitted of charges brought on by the unlawful attack after a lengthy trial.

Roland met Beverly McHill in 1970 at the Stockwell BPP office and approached her by asking, “Do you want me to teach you how to march?” They married two years later. Roland also became a licensed insurance agent, the president of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and the co-executive producer of the film documentary “41st and Central” with Gregory Everett. Roland leaves to mourn his wife Beverly, son Roland Toure’ and daughter Mai, and a host of family, comrades and friends.

Manuel La Fontaine is an organizer for All of Us or None, a national organizing initiative started by formerly incarcerated people to fight against discrimination faced after release and to fight for the human rights of prisoners. He can be reached at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, 1540 Market St., Suite 490, San Francisco, CA 94102, (415) 255-7036, ext. 328, www.prisonerswithchildren.org, manuel@prisonerswithchildren.org.