by Talib Williams

The Bay View is serializing the introduction to “Annotated Tears, Vol. 2,” by Talib Williams, who is currently incarcerated in Soledad, California, and has written the history of that storied place. In the spirit of Sankofa, we learn the past to build the future.

Soledad State Prison is an environment that is almost quite literally haunted by ghosts of the past. When I first stepped foot into the corridor of this place, I was immediately reminded of the historical significance of where I was.

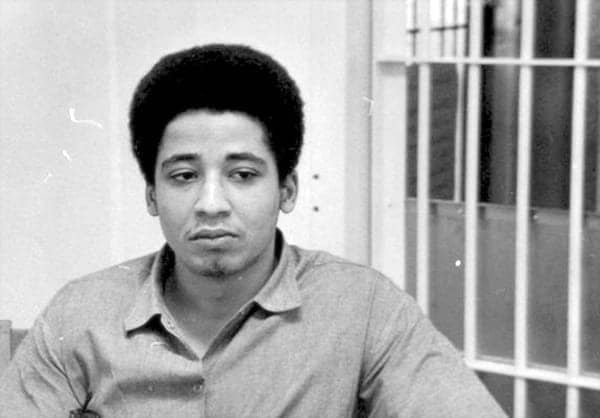

It hadn’t crossed my mind the entire bus ride here, or even while at the previous institution, where I was notified that I’d be transferring. But almost as soon as I entered the hallway leaving R&R, it hit me. I was in the home of George Jackson.

Fifteen years before I was born, an incident would occur here at Soledad that would completely change the prison system. Racist correctional officers who were at odds with the prison’s Black population, began an “incremental release” program, extricating Black and white inmates onto the newly built exercise yard in the prison’s now infamous O-Wing.

The prison had, just months earlier, witnessed numerous racial killings of Black inmates at the hands of their white counterparts. These attacks were instigated by correctional officers, so there was no doubt that letting these groups out together would result in violence.

Johnny Spain, a former inmate, said: “The majority of people in Soledad knew that when the new exercise yard would open that there would be a fight out there.”

Correctional officers and officials were not excluded from this ‘knowing.’ On Jan. 13, 1970, “despite open hostilities, prison officials let both groups of inmates into the yard together, rather than segregating them.”

Fourteen Black inmates and two white inmates were released to the yard after having been on lockdown for several months. The Blacks were ordered to the far end of the yard, while the two white inmates stayed together in the middle of the yard.

It was reported that a fight broke out, and at that point, with no warning shot, Officer Opie G. Miller, described as “an expert marksman,” opened fire from the tower killing three Black inmates; Cleveland Edwards, famous prize-fighter W.L. Nolen, who died on the yard, and Alvin Miller, who died in the prison hospital just hours later. One white inmate was hit in the groin by a ricochet bullet.

Guard Miller’s background was similar to that of other guards; “ex-military, from a Southern state, known to the inmates as a racist.” Based on statements from those who were here in those days, guards just wanted an excuse to shoot Black men, plain and simple.

John Cluchette, one of three people who would eventually be charged with retaliating for these murders, said: “He was going to shoot somebody Black; if it was a fight on the yard or somewhere, he wasn’t going to shoot his own kind. He was going to shoot the other guy.”

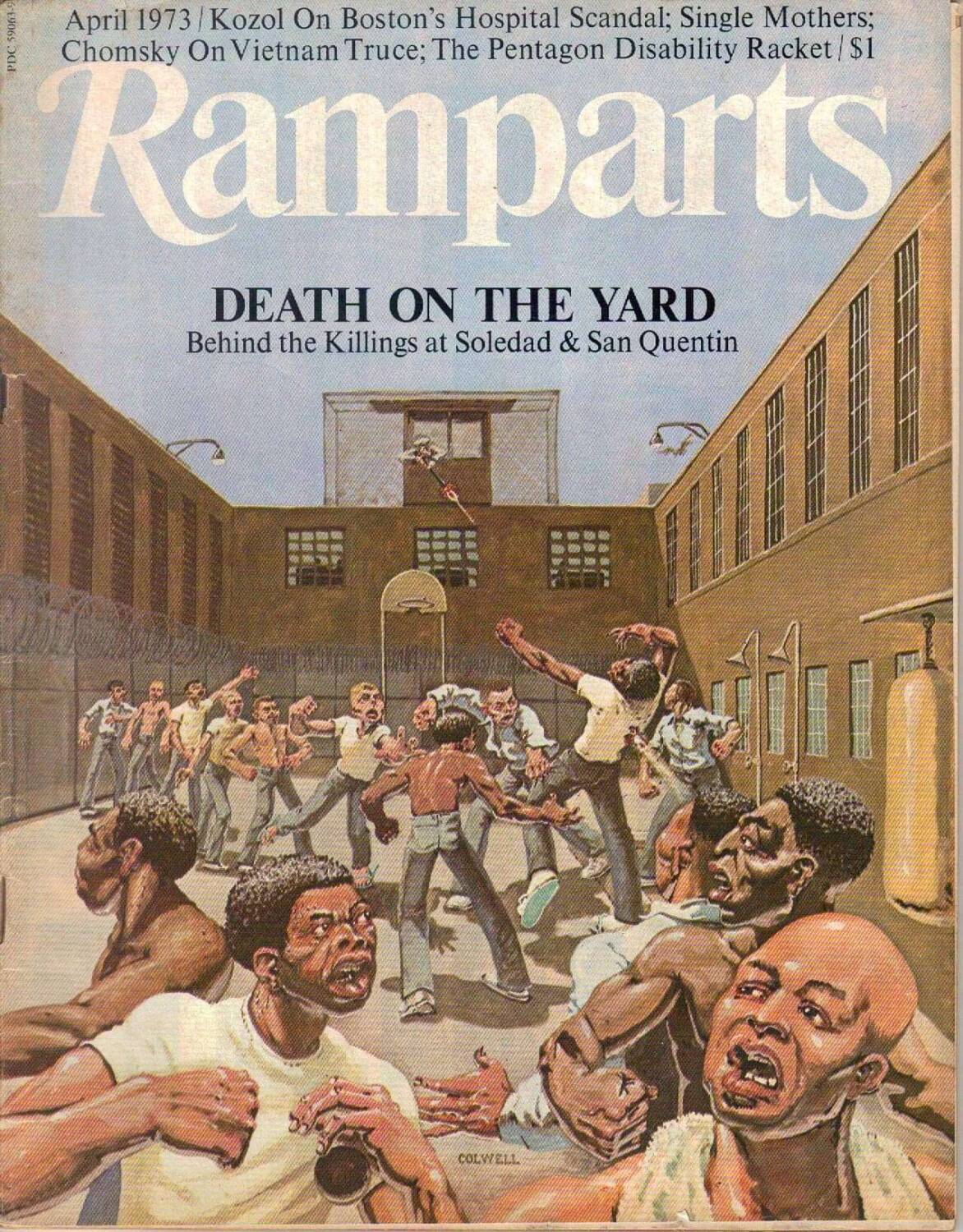

The depiction of this incident was captured in the stereotypical racist imagery of its time, on the cover of Ramparts, an American political and literary magazine published from 1962 to 1975.

Among the Black population, it was clear that this was a setup. To raise attention to the incident and add pressure to the investigation, 13 Black prisoners began a hunger strike. The prison was on high alert. A grand jury was convened immediately. Three days later, inmates were listening to the prison radio when it was announced that the Monterey County grand jury had exonerated Officer Miller with a ruling of “justifiable homicide.”

Thirty minutes later, another correctional officer, John V. Mills, was found dying on the floor of Y-Wing, having been beaten and thrown off the third tier. On his body was left a note reading: “One down, two to go.”

On Valentine’s Day a month later, after an investigation by prison officials, George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo and John Wesley Clutchette – who became known as “The Soledad Brothers” – were indicted for first-degree murder by the same Monterey County grand jury that exonerated Officer Miller.

While awaiting trial, The Soledad Brothers were placed in O-Wing, where Jackson wrote many of the letters that would eventually become “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson.” In the intro to “Soledad Brother,” re-released with a forward by Jackson’s nephew Jonathan Jackson Jr., we read about them awaiting trial:

“The accused men were brought in chains and shackles to two secret hearings in Salinas County. A third hearing was about to take place when John Cluchette managed to smuggle a note to his mother: ‘Help, I’m in trouble.’ With the aid of a state senator, his mother contacted a lawyer, and so commenced one of the most extensive legal defenses in U.S. history.

“According to their attorneys, Jackson, Drumgo and Clutchette were charged with murder not because there was any substantial evidence of their guilt, but because they had been previously identified as Black militants by the prison authorities.”

“The logical place to begin any investigation into the problems of California prisons is with our “pigs are beautiful” Gov. Reagan, radical reformer turned reactionary.

Influenced by the politics of the nation, California’s Gov.Ronald Reagan had a specific view of Black America that made its way into the prison system and into the very way in which Black inmates were viewed and treated. Nothing describes this reality as clearly as Jackson’s own words. In a letter to his lawyer, Fay Stender, recorded in his book “Soledad Brother,” he stated the following:

“Dear Fay,

“On the occasion of your and Sen. Dymally’s tour and investigation into the affairs here at Soledad, I detected in the questions posed by your team a desire to isolate some rationale that would explain why racism exists at the prison with ‘particular prominence.’ Of course the subject was really too large to be dealt with in one tour and in the short time they allowed you, but it was a brave scene.

“My small but mighty mouthpiece, and the Black establishment senator and his team, invading the state’s maximum security row in the worst of its concentration camps. I think you are the first woman to be allowed to inspect these facilities. Thanks from all.

“The question was too large, however. It’s tied into the question of why all these California prisons vary in character and flavor in general. It’s tied into the larger question of why racism exists in this whole society with ‘particular prominence,’ tied into history.

“Out of it comes another question: Why do California joints produce more Bunchy Carters and Eldridge Cleavers than those over the rest of the country?

“I understand your attempt to isolate the set of localized circumstances that give to this particular prison’s problems of race is based on a desire to aid us right now, in the present crisis. There are some changes that could be made right now that would alleviate some of the pressures inside this and other prisons.

“But to get at the causes, you know, one would be forced to deal with questions at the very center of Amerikan political and economic life, at the core of the Amerikan historical experience. This prison didn’t come to exist where it does just by happenstance. Those who inhabit it and feed off its existence are historical products.

“The great majority of Soledad pigs are Southern migrants who do not want to work in the fields and farms of the area, who couldn’t sell cars or insurance, and who couldn’t tolerate the discipline of the army. And of course prisons attract sadists.

“To determine how men will behave once they enter the prison, it is of first importance to know that prison. Men are brutalized by their environment – not the reverse.

“After one concedes that racism is stamped unalterably into the present nature of Amerikan socio-political and economic life in general (the definition of fascism is: a police state wherein the political ascendancy is tied into and protects the interests of the upper class – characterized by militarism, racism and imperialism), and concedes further that criminals and crime arise from material, economic, socio-political causes, we can then burn all of the criminology and penology libraries and direct our attention where it will do some good.

“The logical place to begin any investigation into the problems of California prisons is with our “pigs are beautiful” Gov. Reagan, radical reformer turned reactionary.

“For a real understanding of the failure of prison policies, it is senseless to continue to study the criminal. All of those who can afford to be honest know that the real victim, that poor, uneducated, disorganized man who finds himself a convicted criminal, is simply the end result of a long chain of corruption and mismanagement that starts with people like Reagan and his political appointees in Sacramento. After one investigates Reagan’s character (what makes a turncoat) the next logical step in the inquiry would be a look into the biggest political prize of the state — the directorship of the Department of Correction.

“All other lines of inquiry would be like walking backward. You’ll never see where you’re going. You must begin with directors, assistant directors, adult authority boards, roving boards, supervisors, wardens, captains and guards. You have to examine these people from director down to guard before you can logically examine their product. Add to this some concrete and steel, barbed wire, rifles, pistols, clubs, the tear gas that killed Brother Billingslea in San Quentin in February 1970, while he was locked in his cell and the pick handles of Folsom, San Quentin and Soledad.

“To determine how men will behave once they enter the prison, it is of first importance to know that prison. Men are brutalized by their environment – not the reverse.

“I gave you a good example of this when I saw you last. Where I am presently being held, they never allow us to leave our cell without first handcuffing us and belting or chaining the cuffs to our waists. This is preceded always by a very thorough skin search. A force of a dozen or more pigs can be expected to invade the row at any time searching and destroying personal effects.

“The attitude of the staff toward the convicts is both defensive and hostile. Until the convict gives in completely, it will continue to be so. By giving in, I mean prostrating oneself at their feet. Only then does their attitude alter itself to one of paternalistic condescension. Most convicts don’t dig this kind of relationship (though there are some who do love it) with a group of individuals demonstrably inferior to the rest of the society in regard to education, culture and sensitivity.

“Our cells are so far from the regular dining area that our food is always cold before we get it. Some days there is only one meal that can be called cooked. We never get anything but cold-cut sandwiches for lunch. There is no variety to the menu. The same things week after week. One is confined to his cell 23½ hours a day. Overt racism exists unchecked. It is not a case of the pigs trying to stop the many racist attacks; they actively encourage them.

“They are fighting upstairs right now. It’s 11:10 a.m., June 11. No Black is supposed to be on the tier upstairs with anyone but other Blacks but – mistakes take place – and one or two Blacks end up on the tier with nine or 10 white convicts frustrated by the living conditions or openly working with the pigs. The whole ceiling is trembling.

“In hand-to-hand combat we always win; we lose sometimes if the pigs give them knives or zip guns. Lunch will be delayed today, the tear gas or whatever it is drifts down to sting my nose and eyes. Someone is hurt bad. I hear the meat wagon from the hospital being brought up. Pigs probably gave them some weapons.

“But I must be fair. Sometimes (not more often than necessary) they’ll set up one of the Mexican or white convicts. He’ll be one who has not been sufficiently racist in his attitudes. After the brothers (enraged by previous attacks) kick on this white convict whom the officials have set up, he’ll fall right into line with the rest.”

Send our brother some love and light: Talib Williams, V69247, CTF CW-121, P.O. Box 689, Soledad CA 93960. And visit his website, www.talibthestudent.com.