A study of the manpower implications of small business financing

by Joseph Debro

A 1968 book-length report, titled “A Study of the Manpower Implications of Small Business Financing: A Survey of 149 Minority and 202 Anglo-Owned Small Businesses in Oakland, California,” was sent to the Bay View by its author, Joseph Debro, prior to his death in November 2013, and his family has kindly permitted the Bay View to publish it. The survey it’s based on was conducted by the Oakland Small Business Development Center, which Debro headed, “in cooperation with the small businessmen of Oakland, supported in part by a grant, No. 91-05-67-29, from the U.S. Department of Labor, Manpower Administration, Office of Manpower, Policy, Evaluation and Research.” Project co-directors were Jack Brown and Joseph Debro, and survey coordinator was Agustin Jimenez. The Bay View is publishing the report as a series. A prolog appeared in the December 2013 Bay View, Part 1 in January 2014, Part 2 in February, Part 3 in April, Part 4 in May, Part 5 in June, Part 6 in August, Part 7 in October, Part 8 in November, Part 9 in January 2015, Part 10 in March, Part 11 in May, Part 12 in October and this is Part 13 of the report.

III. Oakland’s profile of poverty

All of the ills which have aggravated possibilities for economic growth and development in urban centers throughout the nation are present in Oakland, the focus of our study. As in other core American cities, important demographic changes have ushered in significant alterations in Oakland’s stance concerning housing, employment, health, welfare and business environments of its inhabitants and the dependent populations in the Bay Area.

Oakland has increased its non-white and Spanish surnamed populations from 4.6 percent and 2 percent respectively in 1940 to 34.5 percent and 8 percent, respectively, in 1965. The Anglo population declined during this same period. This shift in the racial and ethnic composition has produced serious repercussions concerning housing, health and welfare problems and has contributed to the formation of a gigantic slum spread over three East Bay cities.

Because of the proclivity to residential segregation as non-Whites and Spanish surnamed peoples gain numerical strength in a heretofore all-Anglo neighborhood, the younger and more affluent Anglos leave in search of more exclusive sections of the city or county. Since the first foothold for minority groups is in the older sections of metropolitan areas, housing is often dilapidated and run down.

Since the newcomers are less able to maintain homes because of precarious employment patterns forced upon them by the prevailing society, already deficient housing tends to deteriorate even more rapidly. Minority families tend to be larger than Anglo families; as a result, they are exposed to the dangers of overcrowding and poor health conditions.

Negro homes tend to have females as household heads, the adult males being absent or non-providers. These circumstances lead to a higher incidence of dependence upon public assistance. At the same time the incidence of crime increases. As all of these processes continue, the neighborhood quickly becomes a ghetto.

In so doing, one of the economic bulwarks of the community – the conglomerate of small business and the scope and variety of their services – collapses or is altered drastically. And as businesses decline or become specialized in the sale of goods and services to an impoverished population, the local employment picture is severely affected, further exacerbating an already critical situation.

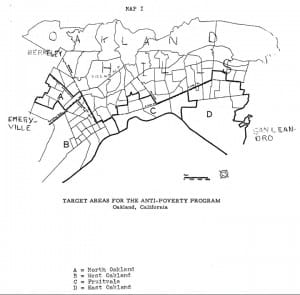

In this section, we review some demographic and socio-economic changes of the ghetto, or Target, and middle class, or non-Target, areas of Oakland, as a prelude to the presentation of results of a survey of 351 small businesses in both sections of the city.

Geography of Oakland

Oakland is located on the eastern side of San Francisco Bay and is the seat of government for Alameda County. It is the fifth largest city in California and occupies about 53 square miles.

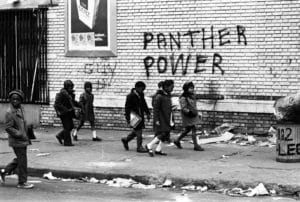

The Flatlands incorporate the converse features of those represented in the Hills. The lower socio-economic classes reside there; these tend to be poor Anglos, Negroes and Spanish-surnamed persons. Homes are overcrowded, schools are poor, and unattractive streets and shops abound. The number of arrests is greater as is the number of people receiving public assistance.

In addition, the Flatlands include three major commercial areas: the highly industrialized bay zone with its complex system of elevated freeways; the downtown “heart of the city,” which includes large department stores, private and public offices, a “Chinatown” and a number of cheap hotels housing indigent elderly people; and the elegant eating and nightclubbing center of Jack London Square. A large body of water, Lake Merritt, graces a small portion of the Flatlands; around it are a number of high-rise apartments, a few public buildings and the imposing Kaiser Center.

Further east, an impressive sports complex has been recently constructed – the Oakland Stadium and Coliseum. Still further to the east, the airport provides a modern transportation link, along with the traditionally important railroad and shipping terminals, to the rest of California, the nation and the world.

Between the airport in the extreme southeast part of the Flatlands with North Oakland, Emeryville and South and West Berkeley to the north, there is a continuous blanket of rundown housing interspersed with pockets of heavy, intermediate, and light industrial and commercial establishments. The several major commercial arteries are lined for miles with small businesses that provide local shopping facilities for the area residents.

Joseph Debro, born Nov. 27, 1928, in Jackson, Miss., and a pillar of Oakland until his death on Nov. 5, 2013, was president of Bay Area Black Builders and of Transbay Builders, a general engineering contractor, former director of the Oakland Small Business Development Center and the California Office of Small Business, co-founder of the National Association of Minority Contractors and a bio-chemical engineer.