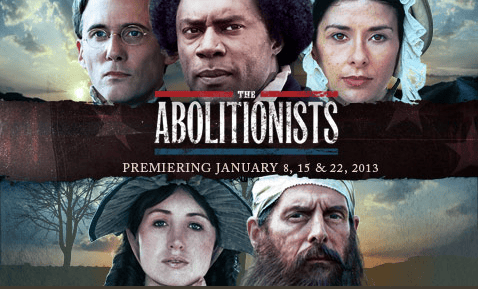

Part 1 of ‘The Abolitionists’ airs Tuesday, Jan. 8, 9 p.m., on KQED

by Truth Minista Paul Scott

“Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamp.” – “Fight the Power” by Public Enemy

The year is 2020, and Goebbels Entertainment Co. has just released its Academy Award nominated documentary, “Rap Unchained,” about how Hip Hop was successful in emancipating millions of Black children from mental slavery during the late ‘80s. While it briefly mentions the contributions of a few Black rappers of the time, the majority of the film is dedicated to one great man who risked his life by speaking out on behalf of millions of oppressed African Americans. This great hero is none other than the rap abolitionist himself, Vanilla Ice.

Like many other topics regarding history, the Abolitionist Movement has been subject to historical revisionism and an attempt by white America to pick our heroes.

Although the film’s trailer proudly proclaims that “if it had not been for the abolitionists, the United States would have thoroughly been a slave nation,” historian Herbert Aptheker wrote in his book , “American Negro Slave Revolts,” that there were more than 200 slave rebellions in this country.

Like many other topics regarding history, the Abolitionist Movement has been subject to historical revisionism and an attempt by white America to pick our heroes.

What is also glossed over by historians is the fact that while many of the white abolitionists did not agree with slavery as an institution, they themselves were still white supremacists who believed that Black people were innately inferior to Whites. Just because an animal rights activist might protest against cruelty to Fido, the pit bull, doesn’t mean that he wants to take him out for dinner and a movie.

Of course, I’m not the first to point this out. In 1837, Rev. Theodore Wright told the New York Slave Anti-Slavery Society that their doctrine must include “recognizing all men as brothers.”

Although Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” is applauded for the role it played in raising awareness about slavery, in his book , “Race: The History of an Idea in America,” Dr. Thomas Gossett claimed that the novel still “made it quite clear that, in spite of the Negro’s humility and aptitude for religion, he is innately inferior.”

It must be also noted that the idea that groups whose religious convictions should have made them longtime allies in the fight against slavery has also been blown way out of proportion. In her book , “Criminalizing of a Race,” Dr. Charshee McIntyre revealed that “as representatives of the emerging capitalist order, reformers could extend charity to the lowliest segment of laborers, but not even the Quakers could view Blacks as potential autonomous beings.”

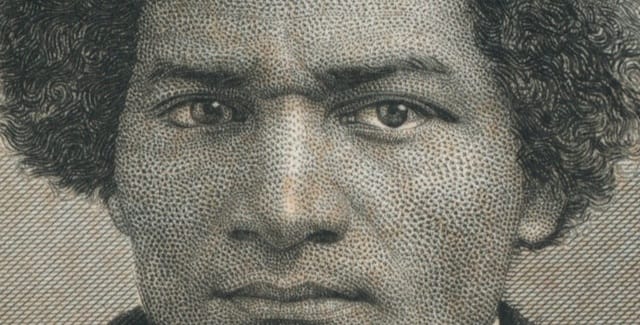

Douglass, however, believed that Black people should have been at the head of the Abolitionist Movement.

Although much has been written about the white Jewish connection to Black suffering, Harold Cruse wrote in, “Plural but Equal,” that it was not until 1915, after the lynching of Leo Frank by a white Atlanta mob, that Jews began to identify with the suffering of African Americans. Cruse writes that the idea that the Jewish community cared much about Black folks prior to that time is “an inaccurate generalization because it was never explained how Jews as a group were involved in contrast to certain individual Jews.”

The main issue here is that the further that we get away from a time period, the more distorted the historical accuracy becomes. If we are not careful, even modern phenomena such as Hip Hop will eventually become distorted.

If we are not careful, our grandchildren will believe that just because Vanilla Ice was popular during the same time period as conscious artists such as Brand Nubian, then he was something other than a cheap, whitewashed version of MC Hammer. Or that even though a white rap group was called “Young Black Teenagers,” they may believe that they were a socially conscious group, rather than a gimmick to prove that white kids could rap.

As we move forward, it must be noted that many of the so-called depictions of “Black History” fictitious or otherwise, have been told from the viewpoint of non-Black people, from “Django” to “The Abolitionists.” Thus we find ourselves in the same dilemma as Frederick Douglass, almost a century and a half later.

The main issue here is that the further that we get away from a time period, the more distorted the historical accuracy becomes. If we are not careful, even modern phenomena such as Hip Hop will eventually become distorted.

The solution is that African Americans must become experts in the field of their own history, as no other racial group would dare trust the interpretation of their culture to others.

This is why we have started the Black by Nature, Conscious by Choice Campaign. During the late ‘80s, the rap group Public Enemy had as its mission to raise up 5,000 Black leaders. So, our task in 2013 is to raise up 5,000 Black scholars who will be experts in Black history, so they can defend our culture against distortions and teach the truth to our future generations.

As Nas said once, “I can.” “If truth is told, the youth can grow. Then learn to survive until they gain control.”

Truth Minista Paul Scott’s website is No Warning Shots Fired.com. For more information on Black by Nature, Conscious by Choice, contact info@nowarningshotsfired.com. Follow on Twitter @truthminista.