by Jeff Kaye

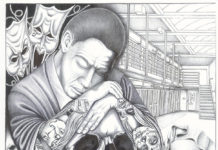

The conditions at Security Housing Units (SHU) at Pelican Bay Prison and other supermax prisons clearly constitute torture and/or cruel, inhumane treatment of prisoners. They rely on the use of severe isolation or solitary confinement, the effects of which I’ve written about before in the context of the Bradley Manning case — see here and here.

At Pelican Bay, the prisoners in “administrative segregation” are locked in a gray, concrete 8 by 10 foot cell, 22 1/2 hours per day. The rest of the time is spent alone in a tiny concrete yard, if that privilege is granted. There is no human physical contact, no work and no communal activities. If the prisoner has enough money, he can purchase a TV or radio. Meals are pushed through a slot in the metal door.

An end to solitary confinement, and in particular to long-term solitary confinement of an indeterminate nature, is one of five “core” demands of the hunger strikers.

Another key demand concerns the onerous and sinister “debriefing” process. The prisoners are asking the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to “A) cease the use of innocuous association to deny an active status, B) cease the use of informant/debriefer allegations of illegal gang activity to deny inactive status unless such allegations are also supported by factual corroborating evidence, in which case CDCR-PBSP staff shall and must follow the regulations by issuing a rule violation report and affording the inmate his due process required by law.”

Dr. Corey Weinstein elaborated on the “debriefing process” in an article on Prison Legal News:

“More than 50 percent of the men in SHU are assigned indeterminate terms there because of alleged gang membership or activity. The only program that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) offers to them is to debrief. The single way offered to earn their way out of SHU is to tell departmental gang investigators everything they know about gang membership and activities, including describing crimes that they have committed. The department calls it debriefing. The prisoners call it ‘snitch, parole or die.’ The only ways out are to snitch, finish the prison term or die. The protection against self-incrimination has collapsed in the service of anti-gang investigation.”

The “debriefing” process is set up by statute. It is a long-term process whereby the prisoner “volunteers” to “debrief,” i.e., to snitch upon other prisoners and identify them as “gang” members. The debriefing prisoners are segregated in their own unit for many months, often more than a year. If they fail to finish the “debriefing” process, they lose whatever credits towards release they may have accumulated during the debriefing process.

The case of Tcinque Sampson

An example of the arbitrary nature of the “rewards” allowed to debriefed convicts can be shown by a filing a few weeks ago in the California Court of Appeal, First Appellate District, Division One, in the case of Tcinque Sampson.

Sampson was sent to prison in 2008 for two years and eight months for grand theft. He was subsequently “known to be a validated member of the prison gang known as the ‘BLACK GUERILLA [sic] FAMILY’ (BGF) per Institutional Gang Investigator (IGI), Officer G. Garrett,” and sent into “Administrative Segregation” (SHU unit).”

If he could get enough credits for good behavior, he could have possibly been released in December 2010. In an effort to get out of isolation sooner, he volunteered, it appears, sometime in 2009 for the “debriefing” program.

According to the legal brief, “During a hearing with the chief deputy warden on September 23, 2010, the petitioner inquired why his original release date had not been reinstated given that he had submitted all of the information that had been requested of him with regard to debriefing. On September 29, 2010, the petitioner was informed that he ‘was “on the list” but the “list” was very long and that is why it was taking so long.’ A few days later, Sampson told prison officials he ‘was no longer interested in debriefing because the institution had not honored its bargain with [him] to grant credits in exchange for debriefing.’”

Last December, the Del Norte County Superior Court granted, in part, a pro se petition for writ of habeas corpus, saying the new CDRC regulations about credits “violated the ex post facto clauses of the federal and state constitutions.” But the appellate court overturned that ruling. Their reasoning tells us a great deal about how state authorities define who is or isn’t a “validated” gang member.

In the end, as we shall see, Sampson’s refusal to engage in the debriefing process supposedly proved he was a gang member and worthy of administrative segregation, or long-term solitary confinement. Bold type in the quote below are added for emphasis:

“Petitioner’s ineligibility for conduct credit accrual is not punishment for the offense of which he was convicted. Nor is it punishment for gang-related conduct that occurred prior to January 25, 2010, since petitioner was not stripped of conduct credits he had already accrued. It is punishment for gang-related conduct that continued after January 25, 2010.

“Petitioner maintains he ‘did nothing’ after January 25, 2010 to bring himself within the ambit of the amended statute, but we see the matter differently. ‘“Gangs, as defined in [California Code of Regulations, title 15] section 3000, present a serious threat to the safety and security of California prisons,” and “[i]nmates and parolees shall not knowingly promote, further or assist any gang as defined in section 3000.”‘ (In re Furnace (2010) 185 Cal.App.4th 649, 657.) The ‘validation’ of a gang member involves no more and no less than the CDCR’s recognition of at least three reliable, documented bases (“independent source items”) for concluding that an inmate’s background, person, and/or belongings indicate his or her active association with other validated gang members or associates, and at least one of those bases constitutes a direct link to a current or former validated gang member or associate. (Ibid.; See Cal. Code Regs., tit. 15, §§ 3378, 3321.) For purposes of placement in a SHU, active gang membership or affiliation is considered ‘conduct [that] endangers the safety of others or the security of the institution’ and ‘a validated prison gang member or associate is deemed to be a severe threat to the safety of others or the security of the institution’ warranting an indeterminate SHU term. (Cal. Code Regs., tit. 15, § 3341.5, subd. (c) & subd. (c)(2)(A)(2).)

In the end, as we shall see, Sampson’s refusal to engage in the debriefing process supposedly proved he was a gang member

“Once ‘validated,’ an inmate’s continued active membership or affiliation in the gang and placement in a SHU continues until one of three things happens: (1) the periodic, 180-day review of the inmate’s status by the classification committee results in his or her release to the general inmate population (Cal. Code Regs., tit. 15, § 3341.5, subd. (c)(2)(A)(1)); or (2) he or she becomes eligible “for review of inactive [gang] status” after six years of noninvolvement in gang activity (Cal. Code Regs., tit. 15, § 3378, subd. (e)); or (3) he or she initiates and completes the ‘debriefing process,’ thereby demonstrating that he or she has dropped out of the gang. (Cal. Code Regs., tit. 15, § 3378.1.) Unless and until one of these three eventualities come to pass, an inmate continues to engage in the misconduct that brings him or her within the amendment’s ambit.”

But these prisoners in supermax are the worst of the worst. Aren’t they in harsh administrative conditions because they have brutally murdered someone or worse? According to the California Code of Regulations, Title 15, Section 3315, there are 23 “serious rule violations” that can send an inmate to an SHU for a determinate time. These include “acquisition or exchange of personal or state property amounting to more than $50 … tattooing or possession of tattoo paraphernalia … possession of $5 or more without authorization … [and] refusal to work or participate in a program as assigned,” among others.

Certainly violence or “mass disruptive conduct” is included in these codes, but so are “acts of disobedience or disrespect” or the perceived “threat to commit” a disruption or breach of security, including the “threat” to “possess a controlled substance.”

From Pelican Bay to Guantanamo Bay

The parallels with the regime instituted by Department of Defense officials at Guantanamo are stunning. Simply replace “gangs” with “Islamic jihadists.” And, as at Guantanamo, the emphasis is on coercing cooperation and collaboration with state authorities. There is an emphasis on fingering other prisoners, thereby building up a case for an even greater threat against state authorities who must have recourse to even more coercion and wielding of state power, all in the name of security, even while constructing the bricks for the edifice of fear out of the very actions of state repression they exercise.

Indeed, quite recently, Jason Leopold and I published documentary evidence that the very SERE techniques that were “reverse-engineered” for use as torture at Guantanamo, Bagram and various “black site” prisons — including, perhaps, the new CIA black sites revealed by Jeremy Scahill in an important new article at The Nation — were originally conceived to fully “exploit” the prisoner, including production of false confessions and the recruitment of double agents and informants.

One wishes, at least, that this was all a recent phenomenon, one that can be “reformed” by a stroke of a pen. But the institution of state repression has sunk its tentacles deep into the body politic. The conditions at California’s prisons are indicative of conditions at other state prisons and federal prisons, and the situation is out of control. Politicians, wedded to law and order rhetoric, are leery of doing anything to change the situation.

The use of forced confessions, indeterminate sentences, harsh punishments and torture were the kinds of inhumane penal conditions that a key member of the Enlightenment, Cesare Beccaria, condemned over 200 years ago in his influential book, “On Crimes and Punishments”:

“If punishments be very severe, men are naturally led to the perpetration of other crimes, to avoid the punishment due to the first. The countries and times most notorious for severity of punishments were always those in which the most bloody and inhuman actions and the most atrocious crimes were committed; for the hand of the legislator and the assassin were directed by the same spirit of ferocity, which on the throne dictated laws of iron to slaves and savages, and in private instigated the subject to sacrifice one tyrant to make room for another.”

From Pelican Bay to Guantanamo Bay, the practice of unnecessarily harsh prison conditions amounting to torture needs to end. The hunger strikers at Pelican Bay and elsewhere, whether criminals or not, are putting their lives on the line for the sake of basic human dignity.

The countries and times most notorious for severity of punishments were always those in which the most bloody and inhuman actions and the most atrocious crimes were committed.

We need to take notice, and then take action. For more information and to sign their online petition, visit the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity website.

The hunger strikers at Pelican Bay and elsewhere, whether criminals or not, are putting their lives on the line for the sake of basic human dignity.

Jeffrey Kaye is a psychologist active in the anti-torture movement. He works clinically with torture victims at Survivors International in San Francisco. His blog is Invictus; as “Valtin,” he also regularly blogs at Daily Kos, Docudharma, American Torture, Progressive Historians and elsewhere.

Store

Store