by Steve Martinot

After Germany’s defeat in World War II, the leadership of the Nazi Party was brought to trial in what has become known as the Nuremberg Process. From that process, new social principles emerged, concepts such as “genocide” and “crimes against humanity.”

Naked and arbitrary aggression was outlawed, as was the concept of collective punishment (retaliation against a group for the act or existence of an individual). And to this it added as a social principle that every individual had the responsibility to refuse an illegal command – whether in the army, the police, an institutional administration or on the street.

In this article, the second in a series of three, I continue an examination of certain California prison Rules Violation Reports issued against a man in Pelican Bay named Abdul Olugbala Shakur. In the previous article, I argued that the prison administration’s actions amount to a form of collective punishment.

Under the aegis of repressing a “gang” called the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF), the administration carried on a witchhunt against the political thinking of many Black prisoners and punished them by solitary confinement. Insofar as a witchhunt enforces the prohibition of ideas, the Nuremberg Principle requires all prison guards to refuse to enforce that prohibition.

The opposite occurs. This article will look at the notion of prison gang, its relation to the prisoner’s need for defense and how that affects us beyond the prison wall.

On Shakur

As described previously, Shakur was charged with rules violations because of things he wrote in private letters to friends. In these letters, he speaks of the New Afrikan independence movement as a source of self-determined identity for African Americans and the role New Afrikan Revolutionary Nationalism (NARN) can play as part of ongoing resistance against anti-Black racism.

He also speaks of the George Jackson University (GJU), a school for learning Black and anti-colonialist history and resistance, of which he is a founder and open proponent. He proposes it as a means of establishing peace and unity between warring street gangs in the nation’s Black communities.

Shakur was himself involved in the “Agreement to End Hostilities” in California prisons that helped bring about the massive hunger strike of 2013, calling attention to denial of human rights in the prisons. And these write-ups charge and punish Shakur for advancing these thoughts.

Each report had the same form. A guard had read the letters, had written him up and then repeated certain “facts” about him – for instance, that he was a “validated” member of the BGF. The hearings then simply involved linking his thoughts to the BGF. Even when a letter quoted the warden’s description of the BGF, it was considered “gang activity.” As Shakur argued, this made him – and some 30 others in the Pelican Bay SHU – political prisoners.

The procedure is simple. The administration links certain ideas to an alleged group (which may or may not exist), outlaws the group as a “threat to prison security” and thus bans the ideas as constituting outlawed activity. Thus, it simply asserts that the GJU is a group for the “dissemination of BGF literature and training materials to communities and inmates.” Where this literature is to be found remains unstated.

GJU brochures give long lists of works about Black resistance, African history and culture, and African American political organization. But there is no mention of BGF “literature.” Nor does any appear on the internet (the many police oriented web pages that discuss the BGF) or in the UC Berkeley library catalogue.

Similarly, when Shakur refers to “us” in his letters, the administration adds parenthetically that this means “BGF members.” Thus, he is denied his personhood.

The administration links certain ideas to an alleged group (which may or may not exist), outlaws the group as a “threat to prison security” and thus bans the ideas as constituting outlawed activity.

I know of a prisoner who had a book by George Jackson sent to him. It came from the publisher, it went through the mail room, the censors and inspectors, and was delivered to his cell. Months later, a different guard found the book in the person’s cell, and wrote him up as a gang member, resulting in his being thrown in solitary.

Gangs in prison

There are gangs in the prisons, and they sometimes fight among themselves. That is true. “Gang” is defined by the state (CCR §3000, rule 3023a) as any group of three or more with a common name or identifying sign or symbols whose members have knowingly engaged in planning, organizing, threatening or financing or committing unlawful acts.

If any unlawful acts are attributed to Shakur, they are not mentioned in his write-ups. He is simply condemned to solitary for having been defined by the administration as a member of the BGF.

How is the BGF defined? The administration uses what is found on the web.

“The BGF was cofounded in 1966 by George Jackson. … The BGF is the most ‘politically’ oriented of the major prison gangs. It was formed as a Marxist-Maoist-Leninist revolutionary organization with specific goals to eradicate racism, struggle to maintain dignity in prison and overthrow the U.S. government. All members must be Black. Though small in number, the BGF has a very strict death oath which requires a life pledge of loyalty to the gang. Prospective members must be nominated by an existing member.”

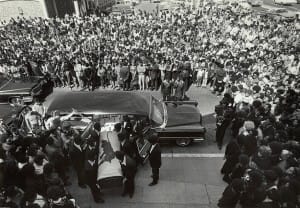

The idea that George Jackson founded the BGF is essential, though its factuality is denied by much police testimony in court. The story of Jackson’s alleged “jailbreak” in 1971, as the reason for his murder in the San Quentin prison yard, is the original unlawful act for which the administration bans the BGF.

It is a fanciful story insofar as Jackson is said to have had one of two kinds of gun, that he had either shot his way into the Adjustment Center (solitary cell block) or shot his way out, was trying to break out by running toward the wall rather than the gate, and was the cause for five people having their throats slit inside the Adjustment Center with no prisoners getting any blood on themselves.

Many gangs are constructed along racial or ethnic lines. Fights between them are at times incited by guards to create an opportunity to shoot a few people and throw some more in solitary.

But all groups of prisoners need a means of self-defense against the administration to preserve personhood and social unity against the combination of racism, contempt and raw power. White prisoners sometimes get recognition for being white. At other prisons, they reaffirm their white personhood by attacking Black prisoners (in tacit alliance with the guards).

All groups of prisoners need a means of self-defense against the administration to preserve personhood and social unity against the combination of racism, contempt and raw power.

If the guards use “race” as an instrument of power against prisoners, white prisoners will use their social hierarchy (white over Black) to avoid being targeted. When the guards use hierarchy – their raw power – as an instrument against prisoners, white prisoners will use race and demand recognition in terms of white solidarity.

Thus, Black prisoners and other prisoners of color have to contend with both guards and white supremacist gangs, like the Aryan Brotherhood. Their need for self-defense is double.

Does the BGF exist?

The question arises about the BGF, does it actually exist? Or is it simply an instrument for the repression of Black people?

From what I have been told, the answer is that it exists. The real question is, in what form does it exist? As an organization, with meetings and by-laws? As the idea of an organization with which people can identify? Or as an identity of resistance to racial oppression? These are important distinctions. And in the outside world, an organization can be all three. But inside, that is more difficult.

For a ban to be legitimate, the administration would have to show the BGF was a real organization. To ban an idea is despotic and unconstitutional. And to ban an identity is cultural genocide.

For its political purposes, the administration seeks to erase these distinctions, banning ideas and identities in the name of banning an “organization.” The power the administration gains by these means adds to the need for defensive organization on the part of the prisoners.

To “prove” an organization exists, there has to be some actual evidence, especially if one is going to condemn people through it. There must be membership lists and procedures by which actions were planned – reports of meetings, charters, rules, initiation rites, manifestos and leaflets etc.

There was actually a constitution written, which the administration would confiscate. But that is not proof, since anyone can write one. It can even emerge from discussions and represent collective decisions made secretly somewhere in the yard. But something more would be needed if the group sought to attract members – which is what the administration’s mention of “nomination” procedures implies.

Ultimately, the administration simply relies on its impunity, its power to define. To state the gang exists becomes proof of that existence. Membership is defined by upholding New Afrikan ideas – or reading George Jackson.

Jackson himself was clear on what he thought, and his strategy was simple. He understood the prison system to constitute concentration camps for Black people, as the Nazi camps did for Jews, and its purpose was to break and destroy all Black people in its clutches.

His own sentence was an atrocity – one-to-life for stealing $72. What galled him was (and I paraphrase) “that they never imagined that I would resist.” His counsel to others is: “We must disabuse them of the idea that destroying us will be easy.” And therein lies the BGF’s “security threat.” Only against a strategy of destruction does resistance become a threat.

For a ban to be legitimate, the administration would have to show the BGF was a real organization. To ban an idea is despotic and unconstitutional. And to ban an identity is cultural genocide.

The administration is also admitting that the BGF’s dedication to eliminating racism is part of that threat. It thus admits that it needs anti-Black racism – and gains power from it.

Shakur is punished for legitimately (under the Nuremberg Principle) upholding the idea of resistance to anti-Black racism. When an idea is criminalized by a power structure to oppress people, a crime is being committed by that power structure. In that sense, the BGF has greater legitimacy under international law than the prison administration itself.

The BGF exists, but not as the administration says it does. The real absence of proof means it exists as a source of identity, an identification with the ideas of anti-racism and human rights.

In focusing on loyalty to the BGF, the administration raises another issue, that of allegiance, which becomes another aspect of threat. If a gang’s purpose is collective defense, then allegiance will not produce disruptive violence, since it is defensive.

Allegiance is a threat because the prison system needs allegiance to itself and not to other organizations. Its own structural criminality – composed of kidnapping, torture, violation of human rights, violation of civil rights, beatings, assault, denial of due process etc. – can be legitimized only through general acceptance of those crimes as legitimate.

Only allegiance to the idea of self-decriminalization will valorize those acts. Thus, any alternate allegiance will disrupt this self-decriminalization. In particular, every guard must give allegiance to the prison system since they are involved in the commission of torture as well.

On the other hand, prisoner self-defense does not require “allegiance” but rather solidarity. Solidarity says, “We stand shoulder to shoulder” and if anything happens, “I have your back.” Allegiance is based on the idea that “I am watching you to insure that you live up to the loyalty that I expect from you.” Solidarity produces an identity of resistance. Loyalty (as allegiance) marks hierarchy and a need for justification.

The difference between allegiance and solidarity is evident in the censorship of the prisoners.

The meaning of censorship

Censorship criminalizes ideas because it punishes those who propound those ideas, such as it punishes Shakur by extending solitary for speaking of NARN or Black August, for instance.

But it has an insidious character. Shakur is accused of “promoting gang activity” when he suggests that the George Jackson University can bring unity and peace among the street gangs of the Black communities because he is “attempting to utilize the NARN concepts to indoctrinate the street gangs.”

The officer testifies that Shakur is aware that promoting the BGF indoctrinates gang activity – though Shakur states that it is constitutionally protected political thought. “Gang activity” thus attaches to the stating of certain ideas. As the officer says, in “coupling the mindset of New Africans with the revolutionary nationalism of NARN, … the teachings of NARN become more than just words.”

But what do they become? Directives? Programming? For the administration, “teachings” indoctrinate. To “teach” is to determine what others will do and think. The implication is that when people hear these ideas, they automatically become active believers, led willy-nilly into gang activity.

Censorship criminalizes ideas because it punishes those who propound those ideas, such as it punishes Shakur by extending solitary for speaking of NARN or Black August, for instance.

By simply bringing the ideas of the GJU to street gang attention, they will be indoctrinated – which must be prevented. For the administration, such readers or listeners are incapable of thinking for themselves. They will be controlled by what they read or hear.

Thus, the administration’s censorship violates the freedom of the reader. The reader cannot be permitted to read what the writer wrote. All readers are both deprived of their freedom and dehumanized at the same time. That means us.

Where the prison administration speaks for Shakur – and criminalizes him in order to decriminalize itself – it also speaks for the reader and criminalizes the reader in advance. Where the prison administration extends the prison to imprisonment inside the prison, it also extends the prison to all people outside it, by violating their freedom as readers.

Let’s look at this carefully. To read a text, one must interpret its words, first their dictionary meaning and then the meaning they bestow upon phrases and sentences. Grammatical structure, as the context for words, changes their meanings and requires interpretation. Finally, one must interpret the flow of sentences to see what the text is doing.

One engages at least three levels of interpretation in order to read something. And one must do this freely. Whatever the author had in mind, the reader’s freedom to interpret signifies that what the reader finds in the text is determined by the act of reading, not the act of writing. Different people read the same piece of writing differently.

In this sense, it is not sensible to say that a piece of writing is “inflammatory,” for instance. The act of being “enflamed” belongs to the reader, not the writer. To make a rule or law against inflammatory writing is nonsense. To permit writing to be disseminated only if it is non-inflammatory is despotic. It denies the reader the freedom to be a person.

And similarly for the notion of “indoctrination.” Writing cannot “indoctrinate” because the reader must be free to read interpretively. Only violence can indoctrinate a person.

The freedom of the writer is guaranteed by the First Amendment as freedom of speech. The freedom of the reader is also guaranteed as the freedom of the press. Though suppression or control of the press can enforce ignorance, the press cannot indoctrinate.

As essential to its self-decriminalization, the prison administration must extend the paradigm of imprisonment far beyond its own walls and destroy alternative ideas. Censorship suppresses the freedom of the reader in order to create a social population that will only read what the administration gives them to read. It is thus an attempt to control the rest of us. It is thus a dehumanization of us all.

To censor an author as a threat is to engage in the collective punishment of people unknown and unidentifiable by curtailing their freedom in the name of punishing the author. It is to blame the author for what the reader thinks.

Note on pornography: There is a similar issue around pornography. Visual pornography, films, pictures and theatrical performances constitute an objectification of sex and sexuality by removing it from the realm of sensuality and shifting it to that of spectacle, an objective interaction between things – things that happen to be body parts.

But it also depends on an objectification of women. In a patriarchal society such as the U.S., male hegemony is already an objectification of women. It establishes a subject-object relation for which men are the subject. What a man does as a person he does as an individual.

As generalized objects – and generalization is a form of violence – women are “mass produced.” Men can walk away from the objectification imposed on them by their performance in pornography. What a woman does as an object is something that happens to her, and thus happens to all women. She cannot walk away from her objectification in visual pornography.

But for literature, the situation is different, because it is written. The reader has to interpret what is written. The film image is not symbolic, but presentational.

Steve Martinot is a human rights activist, organizer and writer and retired machinist, truck driver and professor, most recently at San Francisco State University. He has organized labor unions in New York and Akron and helped build community associations in Akron. He was a political prisoner in New York state charged with contempt of grand jury. He has published eight books, the latest being “The Need to Abolish the Prison System,” and can be reached at martinot4@gmail.com.