by Watani Stiner

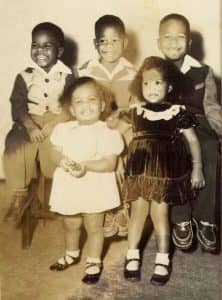

My life began in the Jim Crow South, in Houston, Texas. I remember the segregated world I was born into … the separate water fountains, the back of the bus, the going around to the back door of Mr. Fontnoe’s grocery store to buy milk for my mother and grandmother.

I recall the segregated section of the movie theaters – and the long, seemingly endless net partitioning the giant sandy beaches holding the most popular paddle board, separating the “Colored” folks from the “Whites.” Can you imagine that it once was a reality, a segregated beach!

Yes, I remember as a child, squinting my eyes and peeking through the small holes of the beach net and witnessing all the little White kids playing in the sand. For me and my siblings, it felt as if they were having so much more fun playing in the sand than we could ever have as Negroes.

I tried to make sense of the world around me. But the only way I could grasp my reality, understand what was going on in this segregated world I was thrust into, was through the holy lens of my religious faith, through the eyes of a Catholic child. After all, why else could we not drink from the White fountains, or sit in front of the bus, or go places and do what other White kids could do? It must be because that would be a big Black sin to do so.

Why else would our parents and other grownups go along with it if it were not a sin to do so? God must have intended the world to be this way. To get to heaven, all we had to do was to obey God’s commandments, say our prayers – and stay in our place.

I was just 7 years old when my mother took us on the Greyhound bus from Texas to California, straight to Watts, a more complexly racist world, far removed from the simplicity of grandmother’s gaze, her praying hands and her protective morality.

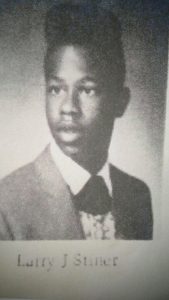

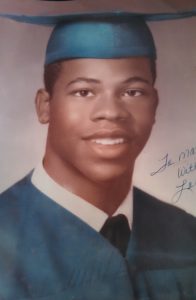

Ten years later, and just three months after my 17th birthday, I married my high school sweetheart, graduated from high school, got a well-paying job at McDonnell-Douglas aircraft company, and became the proud father of my first son: Larry Joseph Stiner Jr.

That was 1965. All I needed in order to become an established upstanding citizen was a house, an obedient dog and a white picket fence. I guess it would be correct to say that we were well on our way to becoming your stereotypical “American Negro” family. I was going to establish and experience the American dream! At least the limited version available to a young Negro family in 1965.

But then, something extraordinary happened that same year, something that would change my life forever …

It was on Aug. 11 of that year, 1965, that the Los Angeles “Watts” revolt exploded. This revolt, sparked by issues of civil rights and a rash of police killings of young Black men, ushered in a wave of uprisings all across this country. Similar to today’s cry and demand by young people that Black Lives Matter, the generational cry of the 1960s was for Black Power!

The Watts revolts had a cathartic impact on me. This phase of our struggle was the culmination of years of civil rights protest and legal frustration over racial discrimination against Blacks in this country.

I watched on television as dogs and water hoses were turned loose on nonviolent protesters in the South. As I watched the horrible images, I became filled with rage. I was angry and, at the time, I couldn’t understand why those civil rights demonstrators on television wouldn’t fight back. How could they be nonviolent in the face of such violence? Why would they not protect themselves against these openly hostile and brutal assaults?

I didn’t want to be like them. I wanted to be part of a more confrontational movement to end police brutality and racial discrimination in this country. I could not and WOULD NOT turn my other cheek! I saw it as a weak, ineffective and humiliating tactic that made absolutely no sense to me, given the centuries of abuse, injustice and humiliation Blacks had already endured in this country.

Therefore, I sided with other young people who had rejected Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of “nonviolence” and adopted a more militant posture: “Freedom by Any Means Necessary.” Malcolm X spoke clearly to my generation as King had spoken to my parents’ generation.

It is important in telling my story to put it into a social context: The 60s was a time when young people all across this country were breaking through racist barriers, opening up closed doors of opportunity, and raising critical questions about the war in Vietnam and the unequal distribution of power and wealth in this country.

It is a parallel of history that the Black Lives Matter movement emerged from incidences of police brutality and injustice which served as the proverbial spark that ignited a prairie fire of resistance, just as it did for my generation. For both generations, there are the same issues: police brutality, economic injustice, racism and white supremacy.

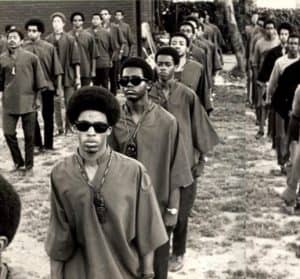

Thus, it was inside this social consciousness and tumultuous climate that I decided to join the cultural nationalist organization “Us” in Los Angeles. I became a Simba Wachanga (Swahili for Young Lion). I very quickly became a dedicated “warrior” for the revolution!

I’m sure everyone reading this has heard of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. They are widely remembered because they effectively seized a moment in history and captured the imagination of the people, and they came to visibly symbolize militant Black resistance in American society at the time. But there were also other significant and relevant groups and organizations during this era fighting against racism and for social justice in this country.

Having been a member of one of these other groups, I often feel that other stories and contributions to the struggle haven’t been included much in the historical narrative of Black Power of that time as it is being told and taught.

There are several reasons for this narrowing of historical players and events. The political, economic and cultural issues we were confronted with during the 1960s were multi-dimensional and complex – as they very well remain today. While the larger society had its own complexity and plurality of voices, the Black Power Movement itself also was not monolithic but had a multitude of different perspectives, personalities and passionate agendas.

As with many other aspects of Black life and experience, the American media tended to want to simplify the story and thus failed to present the diversity of ideas and expressions of the movement to the public. This is not at all to say that the Black Panthers don’t deserve a large and influential place in the history of the time – they do. But I believe that our understanding of history will be greatly enriched by exploring some of the alternative voices engaged in that momentous time and movement.

I believe it is important to know, study and understand the whole history of the Black Power Movement in this country. To know this gives a better understanding of American history – not limited to Black history – in some of its less documented but no less significant aspects.

The Us organization – the name Us came from the idea of “Us” as opposed to “Them,” not as an acronym for “United Slaves,” which has been erroneously repeated in many publications – was founded by Dr. Maulana Karenga in 1965, arising out of the ashes of the Watts Revolt. Karenga is credited with conceptualizing and creating the African-American holiday Kwanzaa, a holiday celebrated today by more than 55 million people throughout the world.

The Us organization at the time I joined was a Black cultural nationalist organization. I was drawn to the philosophy and passionate rhetoric articulating the need to break the psychological stranglehold placed on Black colonized minds by the White enslaver.

We in Us argued that our people must reject the views and values of our oppressors whose interests are not our own; that Black people must realize that our oppressors cannot be our teachers. The Us organization argued for Black self-determination: that we must define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves and speak for ourselves.

Thus, I found myself in the midst of a cultural revolution to win the hearts and minds of Black people. Our belief was that if we failed to win the cultural revolution, then we could not secure the freedom and equality we were fighting for.

To Us, culture was and is a crucial and indispensable weapon in our struggle for liberation, the basis for revolution and recovery. We were fighting for Black Power, which we defined as self-determination, self-respect and self-defense.

The Us organization and the Black Panthers shared many ideological similarities as well as differences. Although we did not agree on everything, we agreed that this society was racist and that a radical change was necessary and only possible through revolution.

These were healthy ideological disagreements, necessary to build and move a movement forward. No one organization had all of the answers, and our strength should have been in a dynamic dialogue which challenged the entire movement to its best expression.

A lesser known but critically important piece of American history – certainly of great importance in our current political situation – is the history of how this government, under the guise of it secret program COINTELPRO, was able to penetrate and manipulate various Black Power organizations in order to destroy them, effectively crushing that potentially vibrant dynamic dialogue amongst the various sectors of the movement.

COINTELPRO is short for COunterINTELligence PROgram, a government operation implemented by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in 1956, to, in his words, “disrupt, discredit, destroy and otherwise neutralize all real and potential [Black] leadership in this county … and prevent the rise of a Black Messiah.”

Hoover’s stated intention was to destroy the Black Power Movement, and he was largely successful at creating an atmosphere of crippling distrust amongst various Black Power groups and members that continues until this very day. He targeted Martin Luther King Jr. as well as many leaders of other Black organizations and groups.

He used secretive and deceitful tactics such as sending death threats and humiliating letters to various leaders of the Black Panthers with the forged signature of the leader of the Us organization, and vice versa, in order to foment retaliation and distrust. It has been well documented that the Black Panthers and the Us organization were targeted specifically and with lethal intent by COINTELPRO.

At the time, such tactics were not common and so a letter with such a threat tended to be believed. Many of the same character assassinations and false narratives invented by the FBI persist today and are uncritically accepted, written into textbooks and research papers, and woven into the fabric of history. COINTELPRO’s insidious and secretive interference tainted allegiances and utilized the age-old tactic of divide and conquer.

In 1968, under an incipient affirmative action program, I enrolled in a cinematography course at UCLA, awaiting placement in the newly formed High Potential Program. There were members of the Black Panther Party as well as the Us organization attending the university under this new program.

Many of the same character assassinations and false narratives invented by the FBI persist today and are uncritically accepted, written into textbooks and research papers, and woven into the fabric of history. COINTELPRO’s insidious and secretive interference tainted allegiances and utilized the age-old tactic of divide and conquer.

Later in that same year, both groups, as part of the Campus Black Student Union, wrestled ideologically over different visions for the hoa board of directors of the new Black Studies Program at UCLA. Black Panthers felt the proposed director was more beholden to Karenga and wanted the students to have a more democratic process rather than have the director appointed by the Community Advisory Board.

The Us organization liked the Community Advisory Board’s choice, and so a conflict arose around the selection process. Regardless of what interpretations have been imposed on this historical narrative, there is no reason to believe that this disagreement between Us and the Black Panthers couldn’t have been resolved peacefully. After all, both groups were passionately engaged in fighting for the same cause, and shared many common friendships and aspirations.

On Jan. 17, 1969, just after a highly controversial meeting about the new director was over, students milled around the cafeteria, continuing the discussion. I was in the middle of such a conversation when, on the other side of the room, a heated argument arose out of the tensions of the week, exacerbated by a silly provocation over disrespectful words exchanged between Tawala, an Us member, and Elaine Brown, a female Panther member.

Three Panthers, Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, John Jerome Huggins and Albert Armour, sought out Tawala and took him to task for his transgression, pistol-whipping him about the face; a shot was fired from Huggins’ gun into the air during this altercation. This first shot silenced the revolutionary chatter and chaos ensued as frightened students scrambled for cover.

Us member Chochezi rushed toward the confrontation and fired at the three Panthers in the course of their thrashing of Tawala. I sought protection behind a table. More shots rang out, leaving me wounded in the shoulder by a Panther’s bullet, and the two leaders of the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party, Bunchy and John, dead on the floor of UCLA’s Campbell Hall, Room 1201.

One of those killed, John Huggins, was a beloved leader in the Panthers’ L.A. Chapter and the 24-year-old husband of Ericka Huggins. She was at home with their three-week-old daughter when she first heard about the killings. And Bunchy’s son would be born just three months later.

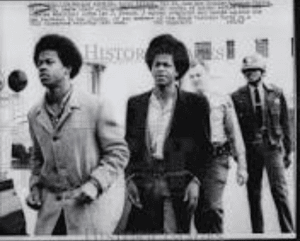

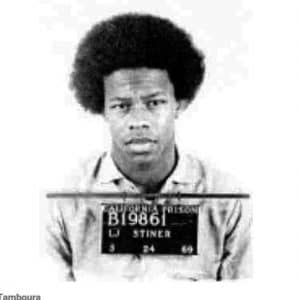

In 1969, my brother and I were tried and convicted of a convoluted “conspiracy to murder” theory invented by the district attorney, though there was no evidence to prove such a conspiracy. In fact, we had turned ourselves in when an all-points bulletin for our arrest was issued because we had no concept that any charges would or could be brought against us, as we had no involvement in the deaths of John and Bunchy and had nothing to hide.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, this was the beginning of my COINTELPRO ordeal. It was certainly within the mission of COINTELPRO to destroy any possibility for collaboration between Us and the Panthers, to arrange for as many leaders and members of the various Black Power organizations as possible to be imprisoned or killed, and to create an atmosphere of distrust and animosity between the groups – a mission in which they were, tragically, successful.

At the time of the shooting, I was a warrior for the revolution, and I was willing to die for the cause. This warrior mindset is essentially militaristic and confrontational. It is “commandist” and combative. It is a mindset that finds justification in violence and accepts casualties of war over preservation of life.

This mindset was not uncommon amidst various parts of the Black Power movement. It’s not difficult to understand how it came to be, after the centuries of violence and terrorism aimed at Black people in this country. Yet it is a mindset that COINTELPRO exploited to create distrust and to obliterate collaboration and unity.

My brother and I were sentenced to “life” in prison. I started serving my time in Soledad before being transferred to San Quentin State Prison. The violence and racism in the culture at large was magnified in prison. We were surprised to discover that in prison, the Black Power groups tended to see themselves more as allies and collaborators, in contrast to the divisiveness on the outside.

Due to our outspokenness and politics, my brother and I found ourselves the target of racist prison guards who were setting up prisoners to be killed. We realized that our lives would soon end if we stayed in prison.

With the help of a Black prison guard and a vocational counselor at San Quentin who recognized our dire situation, my brother and I escaped from prison after serving five years. (That is an amazing story in itself which I am often asked about. I am almost finished with a memoir, “To Stumble Is Not to Fall,” and have written more about that wild adventure there.)

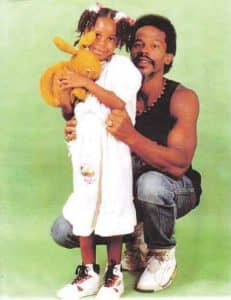

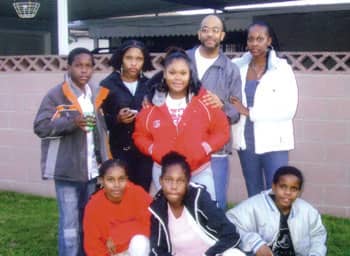

I fled the country to South America, where I lived in self-imposed exile. During the coming two decades, I continued to engage in the political life of the countries I lived in, and also to have a wonderful and ordinary family life. I was a father to nine children and was working to raise my children in a sometimes difficult and challenging environment.

In 1994, 20 years after my escape from prison, trying to provide for my family in a country torn by political and economic strife, I became concerned for the safety and welfare of my Surinamese wife and our children.

I walked into the U.S. Embassy and negotiated my surrender to U.S. authorities. I agreed to return to prison voluntarily if the U.S. government would provide medical assistance and safe passage for my family to the U.S.

I imagined that I would do another three years in prison under my seven-to-life sentence, having already served five, and then would be reunited with my family. (Little did I know that the U.S. government would label me a “domestic terrorist” upon my return and keep me in prison for another 21 years, only releasing me when mandated to reduce overcrowding.)

I was nervous and quite surprised when the State Department was willing to honor my conditions. Nancy Pelosi’s office helped negotiate an agreement, which included immediate relocation for my wife and family to the United States. In fact, they were supposed to be on the same flight.

However, I began to worry when I found myself on a flight without my family, in the custody of an FBI agent. I was returned to San Quentin State Prison to resume my prison sentence. I would soon discover how much more racist and draconian the prison system in this country had become in my absence. Plus, San Quentin was still mad at me for leaving without permission.

I was whisked away to a year in solitary confinement in the “Adjustment Center” and told that because I would be in prison and was unable to care for my children, they would not be allowed entrance into this country. The U.S. government reneged on our carefully-negotiated agreement, and my children were subsequently left homeless in South America for the next 11 years. Needless to say, I was devastated and felt more hopeless than I ever had during those long months in solitary.

After a year, I was allowed to enter into the mainline prison population. I began working in the prison library, anxiously searching for listings of relief agencies, contacting various organizations, and soliciting aid from family and old friends. I tried to use every opportunity to let my suffering children know that I had not abandoned them.

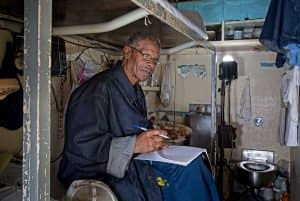

During my fifth year back in prison, I began attending and participating in many prison programs, education and self-help groups that were made available at San Quentin. Through a program called Arts in Corrections, I enrolled in a creative writing class, where I found my voice. I originally intended to write my memoir in order to correct the historical record. I was angry and I felt I had to write things out the way they happened.

But in the course of the writing process and in inner dialogue with the notes my teacher wrote in the margins, I found the story moving from my head into my heart, and I began experiencing compassion for people on the other side of the story, finding more complexity and having a broader view of what happened.

Some time later I was invited to attend a restorative justice workshop of which Fania Davis, Angela Davis’ sister, was the facilitator. I listened carefully to her presentation and was truly moved by the concepts about restoration vs. retribution being discussed in the room.

And I was really moved by Fania’s reframing of such concepts as justice, forgiveness and healing and the importance of being open to dialogue. It resonated with how I had already been expanding my views.

After my experience with that initial meeting, I walked up to Fania, told her who I was, and asked if she would be willing to make contact with Ericka Huggins, to see if Ericka would be willing to sit down with me for a dialogue on what happened on that tragic day. I conveyed to Fania that I wanted to reach out to Ericka for her forgiveness through dialogue in the spirit of truth and reconciliation. I told her that I was moved to do so by her presentation on restorative justice and how one’s culpability in violence doesn’t necessarily have to be about a direct offense committed, but may also come in various indirect forms.

Fania agreed to make contact with Ericka. Days went by without a response. I took it for granted that Ericka was not interested, but I maintained some satisfaction in knowing that I had at least tried.

Three weeks had passed when I received a short note in the mail from Fania, saying that Ericka had agreed to correspond with me and that she was anxiously awaiting my letter.

That fateful day at UCLA in 1969 had irrevocably altered the course of both of our lives. She had lost her husband and the father of her child, as well as having to undergo the chaos and persecution of the government’s vendetta against the Black Panthers. I can’t speak for all the ways the events of that day reverberated through history for her, but there was a tragedy on that day for her that was immeasurable.

For myself, I was shot that day, ultimately arrested and falsely accused, almost had a death penalty imposed, lost my freedom, was forced into exile, spent 26 years incarcerated, and had far too much distance and too many goodbyes with my children on both continents. I was frozen with uncertainty over Ericka’s possible reaction to my invitation to communicate.

For years, I had contemplated what I would say and how I would say it if I were to meet face to face with John or Bunchy’s family. For though I was not responsible for their deaths, their deaths were still shocking and tragic to me, and the losses of those families felt easy to identify with.

I could only try my best to convey to Ericka my thoughts through a letter, and let the woman the campus shooting affected so profoundly know how sorry I was that it ever happened. I wanted to offer Ericka Huggins, John’s widow, my sincere apology for my participation in the warrior mindset that had contributed to the deaths of two human beings. I could only hope that I would be successful in doing so through my letter to her.

I pondered for a few more days, wondering what I would say to Ericka.

Here is what I wrote:

*************

“March 28, 2010

“Dear Ericka:

“In my heart, I have written this letter to you and your daughter many times over; yet, now that I’m confronted with how it might be received by you, I can’t seem to find the “right” set of words. I hope what I have to say is received by you in the loving and compassionate way in which it is felt and conveyed.

“My name is Watani Stiner and during the tumultuous Black Power era of the 60s I was a member of Maulana Karenga’s “Us” organization. On Jan. 17, 1969, I was present on the UCLA campus when a shooting erupted between members of Us and the Black Panther Party. In the aftermath of that tragic encounter, John, your husband, and Bunchy Carter were both shot and killed. I am currently incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison on a “conspiracy” charge related to their deaths.

“Although I did not pull the trigger of the gun that took the lives of John and Bunchy, I have carried a heavy burden of guilt, knowing that I had contributed to and participated in the mindset and atmosphere resulting in the deaths of two human beings.

“My journey of love and sacrifice for my own children has opened up my heart and allowed me to feel the emptiness you must have felt on that dreadful day you learned of John’s death – confusion, the questions, the pain and the realization that your daughter would never get to know her father. For that, I am truly sorry. No words could ever fill the space left in a father’s absence.

“Moreover, it is my contention that the UCLA shooting remains one of the most unresolved conflicts within the Black Power Movement. And because it hasn’t been properly addressed and ultimately resolved, a vacuum and a model were established for the resurgence of violent gang formations in Los Angeles. Notwithstanding external forces of the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), I don’t think it is too much to suggest that the feud between the Crips and the Bloods is in many respect an extension and continuation of the violence between Us and the Panthers.

“After listening to Fania Davis give a talk on ‘restorative justice’ to a group of young men here at San Quentin, I introduced myself to her and expressed my desire to make contact with you for dialogue and reconciliation. Since Fania is actively engaged in promoting restorative justice, I asked her to help me reach out to you and to facilitate the process of reconciliation.

“I trust that with Fania’s guidance we can enter into a process that will help us confront and challenge many of the myths and lingering speculations that have surfaced after the UCLA killings. Hopefully, many of your questions will be asked and answered through honest dialogue.

“I wrestled with what had happened at UCLA and what I would and should have done differently. There is no justification for the killing of another human being. I thought about you and your daughter often, wondering how you and she were making it without John. How were Bunchy’s son and family? I imagined myself meeting up with you and visualized the conversation we would have, what I would say to your daughter, how she and you would respond.

“There must have been many difficult, emotional times as you tried to cope. The many questions that must have plagued the mind of your daughter: what daddy was really like, the things he would have done for me, the places he would have taken me, and his presence at my graduation and marriage. Yes, Ericka, all of the things I have experienced (or wanted to) with my own children were denied your daughter.

“It is said that time heals all wounds. But even if this saying is true, I’m sure it does not remove all of the scars. And I wonder just how many scars were left on you and your daughter over the years following the death of your husband John. ‘Would my act of writing to her bring back terrible memories and open up old wounds?’

“The tragic irony of my situation – still doing time for a 40-year-old conspiracy conviction – seems utterly preposterous. I believe that because there was never any serious dialogue or genuine attempt at conflict resolution between Us and the Panthers, history was unable to reveal to us and teach our children anything about truth, reconciliation and forgiveness. I’m wondering if there is anything that can be done about it now.

“The positive contributions both organizations made to our communities cannot be denied. However, in a culture of violence, absent any creative and bold intervention, the cycle continues. Would you be willing to join me in setting up a truth and reconciliation forum as a model for our youth? I’m sure that there are others from the movement who feel partially responsible for the violence permeating our communities today.

“I also have an emotional and intellectual interest in trying to understand and combat the gang situation in L.A. My two teenage sons, recent residents of this country for almost five years have already been drawn to gangs and one recently consumed by the criminal “justice” system.

“Thank you, Ericka, for receiving my letter. I hope that you and your daughter are well and that you will be willing to communicate. I hope we can begin the necessary process of reconciliation. Of course, there is no guarantee that dialogue will lead to reconciliation, but there is a certainty that we cannot arrive there without it. If nothing more comes of this humble gesture, I’m at least grateful that you’ve received this letter and that I was able to express my feelings of regret at the deaths of John and Bunchy.

“May you and your daughter receive good things without number and many blessings without end. – Watani”

*****************************

Having written and sent the letter off, I tried to let go of any expectation of a response. One afternoon after institutional count, a prison guard called out my name, “Stiner! Your prison number,” he asked.

“B-19861,” I responded.

The guard then handed me a letter.

It read: Ericka Huggins.

I looked at the envelope long and hard. Part excitement … part fear … I waited as if the words were about to shout out at me from inside the envelope. I peeled back the tape from the edges, securing the censored content inside, and slowly eased out the letter.

Here is what Erika wrote:

************************

“April 20, 2010

“Dear Watani,

“Thank you so much for your heartfelt letter. It is amazing how life pulls people apart, turns them, each one, around inside, puts the parts together again and then brings two or more people into each other’s lives again. The universe orchestrates this in a time, place and space appropriate.

“When I first knew that you wanted to begin this dialogue, I was so excited. In my spiritual practice, whenever there is an opportunity for growth and for forgiving old stories, living in the present moment – like a child – I welcome it. In this instance, everyone benefits. I recognize that we must always make a choice between what is beneficial and what is pleasant. I am so grateful that you chose what is beneficial.

“For many years I have wondered what happened on that day at UCLA. Was John happy, smiling before it all happened? Was he thinking about his 3-week-old daughter? Was he aware that he would die? I know, in my heart, that the answer to all of these questions is yes.

“I wondered what really killed John and Bunchy? …somehow I knew that even the person who fired the shots was not at the root of the actions. History as it impacts the present was at play. The history of the United States, the history of John, Bunchy, Ericka, Watani – all of us. Everything coalesced to create that singular event and the many events that arose from it.

“Will those events be filled with love, kindness, compassion, fearlessness, light-heartedness and steady wisdom, or, the opposites? This, our dialogue, contributes to their uplifted understanding, their ability to welcome opportunities to forgive, to move forward, to love.

“That is what I wish also for your children and grandchildren – for all of the world’s children.

“We were ‘wrong’ and we were ‘right’. Life is full of paradoxes and is never simply either-or. My request is that as we ‘talk’ we agree to a both-and principle. Humans are capable of the most heinous actions and the most lovely – all in one day, in one minute. We are all paradoxical beings.

“I appreciate your willingness to be in conversation with me and with yourself. Your self-inquiry touches me at a deep and resonant level.

“I hope that you recognize the liberating power of honesty and forgiveness – not just for others – for yourself. I have spent many years recognizing this freeing and challenging concept – self-forgiveness.

“Thank you very much for writing and reflecting on what I write and writing again …

“May your days and nights be full of peace.

“Ericka”

**************************

Ericka and I would soon learn through our correspondence that we had both been on long, arduous journeys of the mind, heart and spirit as we openly communicated with each other.

Before communicating with her, I was frustrated with my desire for dialogue and reconciliation. It was difficult trying to communicate from a prison cell to the few who were willing to visit and listen to a convicted prisoner; and I honestly did not know how to proceed. My correspondence with Ericka was the closest I had come.

Perhaps it’s important to reiterate here that my apology was not for anything specific that I had done. I did not pull the trigger. I was wrongly convicted and unfairly imprisoned. But I felt compelled to acknowledge the warrior mindset that contributed to the adversarial atmosphere that was at play on that fateful day.

A few people on both sides of the battlefield, Black Panthers and Us, had issues with this reconciliation effort between Ericka and me: On the Us side it was strongly believed that since I had not done anything, I had nothing to apologize for: “Why apologize for something you hadn’t done? After all,” they said, “the Panthers started it!” And on the Panther side, it was felt that Ericka was just being naïve or “too forgiving” for a terrible and irreplaceable loss.

But Ericka and I refused to listen to those negative voices. After more than two years of correspondence, I got my chance to do it in person. In September 2012, I sat down with Ericka Huggins for the first time. Our face-to-face meeting took place at San Quentin State Prison, inside a dull, institutional room which is normally used for parole board hearings.

It was the most emotional engagement of my entire life. And it was also the most fulfilling and rewarding. We talked for five hours about the people, the movement, our children, COINTELPRO, and the state of our youth today; we talked about how we can share our experiences and pass the historical baton on to the next generation. My heart couldn’t have been more full.

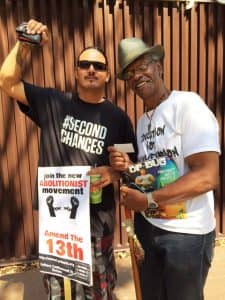

A few months later, on Dec. 21, 2012, a week after the horrific Newtown murders at Sandy Hook Elementary School, Ericka and I participated in a restorative justice symposium at San Quentin. Facing a packed audience of prisoners and outside guests, we told our stories and talked about the spiritual power of forgiveness and the need for truth and reconciliation. Ericka and I have undone some of that COINTELPRO damage and restored our true identities as allies and co-collaborators.

Here is something of what I have come to understand out of this long and difficult journey: We must be courageous in our willingness to put out fires that we did not start. We are all inheritors of legacies and histories that we did not create; we are all unwitting participants in injustices that we don’t consciously support. Without forgiveness, there is no possibility of unity; without truthtelling, there is no possibility of forgiveness.

I urge anyone reading this to find ways to be a part of whatever healing you can join in on, whether or not you were a part of the original damage. Let’s let truth and forgiveness bring us to new possibilities of collaboration, trust and unity. COINTELPRO’s stated mission was to disrupt, discredit and destroy. Let’s be part of a movement going in the other direction – to heal, respect and build up a just world we all want and deserve to live in.

Watani Stiner, keynote speaker at the Millions for Prisoners Human Rights March in San Jose on Aug. 19, walked out of San Quentin into the “free” world on Jan. 11, 2015. He says, “I consider myself a revolutionary elder, a storyteller and a social justice advocate passing the historical baton on to the next generation.” Contact him by email at watani.stiner@gmail.com or by snail mail at 1969 Harrington Ave., Oakland CA, 94601. This story is excerpted from a speech delivered at San Francisco State University that has never before been published.