by Jeanne Theoharis

1. Parks had been thrown off the bus a decade earlier by the same bus driver – for refusing to pay in the front and go around to the back to board. She had avoided that driver’s bus for 12 years because she knew well the risks of angering drivers, all of whom were white and carried guns. Her own mother had been threatened with physical violence by a bus driver in front of Parks, who was a child at the time. Parks’ neighbor had been killed for his bus stand, and teenage protester Claudette Colvin, among others, had recently been badly manhandled by the police.

1. Parks had been thrown off the bus a decade earlier by the same bus driver – for refusing to pay in the front and go around to the back to board. She had avoided that driver’s bus for 12 years because she knew well the risks of angering drivers, all of whom were white and carried guns. Her own mother had been threatened with physical violence by a bus driver in front of Parks, who was a child at the time. Parks’ neighbor had been killed for his bus stand, and teenage protester Claudette Colvin, among others, had recently been badly manhandled by the police.

2. Parks was a lifelong believer in self-defense. Malcolm X was her personal hero. Her family kept a gun in the house, including during the boycott, because of the daily terror of white violence. As a child, when pushed by a white boy, she pushed back. His mother threatened to kill her, but Parks stood her ground. Another time, she held a brick up to a white bully, daring him to follow through on his threat to hit her. He went away. When the Klu Klux Klan went on rampages through her childhood town, Pine Level, Ala., her grandfather would sit on the porch all night with his rifle. Rosa stayed awake some nights, keeping vigil with him.

4. Many of Parks’ ancestors were Indians. She noted this to a friend who was surprised when in private Parks removed her hairpins and revealed thick braids of wavy hair that fell below her waist. Her husband, she said, liked her hair long and she kept it that way for many years after his death, although she never wore it down in public. Aware of the racial politics of hair and appearance, she tucked it away in a series of braids and buns — maintaining a clear division between her public presentation and private person.

5. Parks’ arrest had grave consequences for her family’s health and economic well-being. After her arrest, Parks was continually threatened, such that her mother talked for hours on the phone to keep the line busy from constant death threats. Parks and her husband lost their jobs after her stand and didn’t find full employment for nearly 10 years. Even as she made fundraising appearances across the country, Parks and her family were at times nearly destitute. She developed painful stomach ulcers and a heart condition and suffered from chronic insomnia. Raymond, unnerved by the relentless harassment and death threats, began drinking heavily and suffered two nervous breakdowns. The Black press, culminating in JET magazine’s July 1960 story on “the bus boycott’s forgotten woman,” exposed the depth of Parks’ financial need, leading civil rights groups to finally provide some assistance.

7. In 1965 Parks got her first paid political position, after over two decades of political work. After volunteering for Congressman John Conyers’s long shot political campaign, Parks helped secure his primary victory by convincing Martin Luther King Jr. to come to Detroit on Conyers’ behalf. He later hired her to work with constituents as an administrative assistant in his Detroit office. For the first time since her bus stand, Parks finally had a salary, access to health insurance, and a pension – and the restoration of dignity that a formal paid position allowed.

9. Parks was an internationalist. She was an early opponent of the Vietnam War in the early 1960s, a member of The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and a supporter of the Winter Soldier hearings in Detroit and the Jeannette Rankin Brigade protest in D.C. In the 1980s, she protested apartheid and U.S. complicity, joining a picket outside the South African embassy and opposed U.S. policy in Central America. Eight days after 9/11, she joined other activists in a letter calling on the United States to work with the international community and no retaliation or war.

10. Parks was a lifelong activist and a hero to many, including Nelson Mandela. After his release from prison, he told her, “You sustained me while I was in prison all those years.”

Jeanne Theoharis is professor of political science at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. She received her AB in Afro-American studies from Harvard College and a PhD in American culture from the University of Michigan. She is the author or coauthor of six books and numerous articles on the Black freedom struggle and the contemporary politics of race in the United States. This story, which is taken from “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks” (Beacon Press, 2013) by Jeanne Theoharis, first appeared on The Huffington Post.

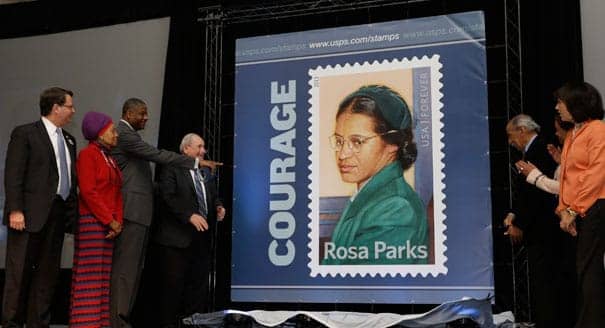

Centenary of Rosa L. Parks (1913-2005): ‘Mother of Civil Rights Movement’ honored in Detroit

by Abayomi Azikiwe, Editor, Pan-African News Wire

In the early 20th century, African Americans were being unjustly imprisoned, assaulted and lynched by white mobs organized into the Ku Klux Klan and other racist organizations. The entire legal system was geared toward maintaining white supremacy – where people were denied the right to vote, to live where they wanted and to achieve educational and career goals commensurate with their wishes and qualifications.

Alabama was considered one of the most violent and racist states in the South. Parks, who would later move to Montgomery, became a seamstress and was elected as secretary for the Montgomery Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1943. She worked alongside E.D. Nixon, a labor organizer and advocate for workers, who was a longtime member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded by A. Phillip Randolph.

Earlier Parks and her husband Raymond would participate in the campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys, a group of African American youth falsely accused of raping two white women on a freight train in 1931. The case gained national attention and drew in support from both the Communist Party and the NAACP.

In 1944, Parks, as secretary of the Montgomery NAACP, helped investigate the gang rape of Recy Taylor, an African American woman. The Chicago Defender would describe the campaign as the most significant effort against racism during the decade.

Parks and other women formed “The Committee for Equal Justice for Recy Taylor.” Taylor was walking home from church in Abbeville, Alabama when she was kidnapped by six white men, taken to a deserted area and repeatedly assaulted.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56 and the modern Civil Rights Movement

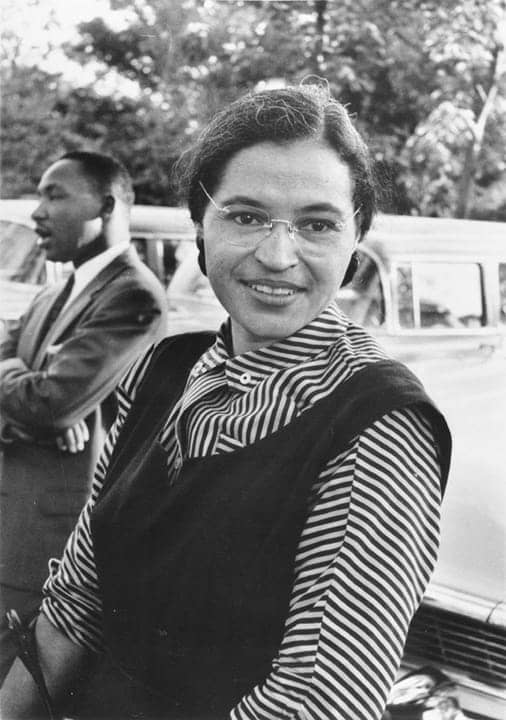

Rosa Parks was thrust into the national spotlight when she was arrested on Dec. 1, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white man in the “colored section” of a city bus. After her arrest, the African American community immediately took action and the Montgomery Improvement Association, formed by E.D. Nixon and led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., called for a citywide boycott that lasted for nearly a year.

During this period, the home of E.D. Nixon was bombed along with the residence of Dr. King. Nevertheless, the community held its ground and eventually won a federal court ruling which outlawed segregation in municipal bus transportation.

The case would initiate the modern civil rights movement that reached its peak between 1955 and 1965, when thousands would march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, demanding universal suffrage. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 would represent a culmination of this phase of the African American struggle for equality and self-determination.

Due to political pressure and harassment, Parks and her husband would leave Montgomery in 1957 and settle in Detroit. Parks continued to work as a seamstress and in 1965 she was hired as a receptionist for the newly-elected Congressman John Conyers Jr. She worked for Conyers until her retirement.

Parks continued to participate in civil rights activities until her senior years. In the mid-1970s, a major thoroughfare, 12th Street, where the Detroit rebellion began in 1967, was renamed in her honor. In her later years, she would form the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development which organized tours of civil rights historical sites for youth.

A series of events have been held to honor her 100th birthday over the last several months. These efforts culminated at the Ford Museum in Dearborn on Feb. 4, which houses the Montgomery city bus where Parks was arrested in 1955. It is a source of interest for students and tourists to the Detroit area.

Anita Peek, the executive director of the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, spoke at the Detroit MLK Day Rally and March held at Central United Methodist Church in downtown Detroit on Jan. 21, the nationally-recognized holiday in honor of the slain civil rights leader. Peek invited the capacity crowd to participate in the centenary activities.

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of Pan-African News Wire, where this story first appeared, can be reached at panafnewswire@gmail.com. Pan-African News Wire, the world’s only international daily pan-African news source, is designed to foster intelligent discussion on the affairs of African people throughout the continent and the world.